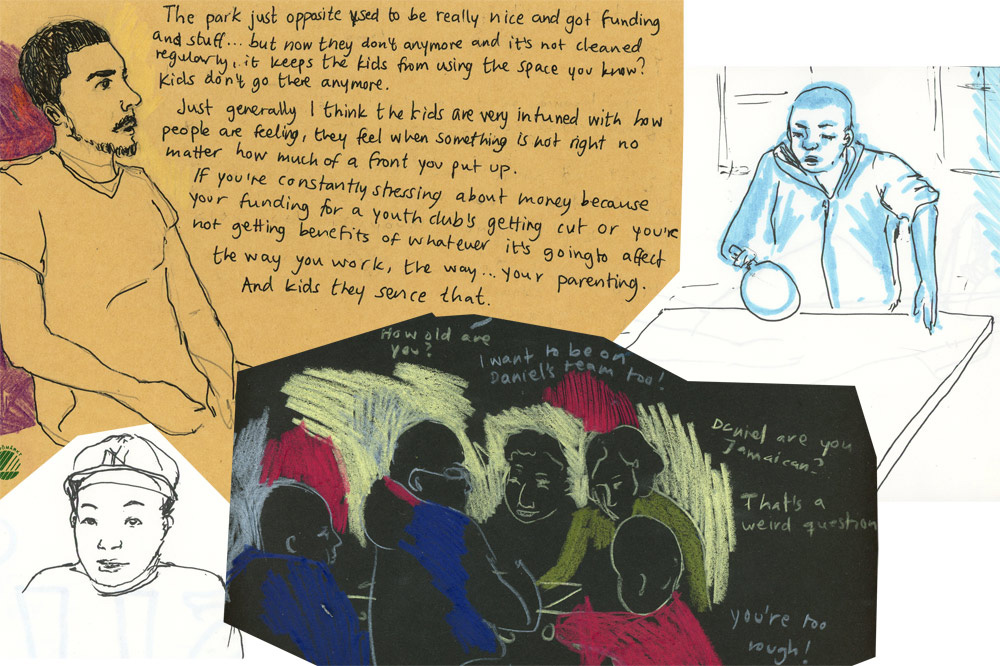

Scenes from a youth club in Peckham

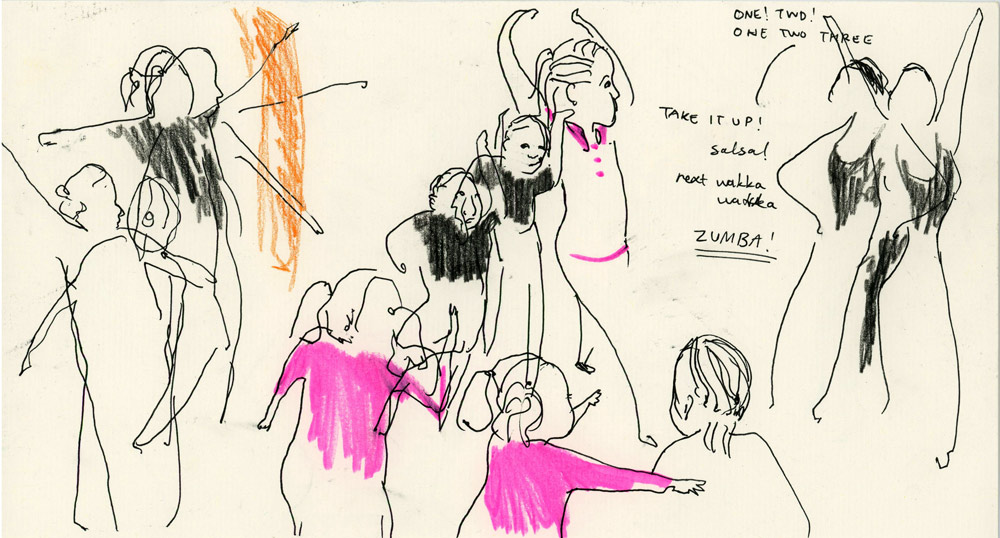

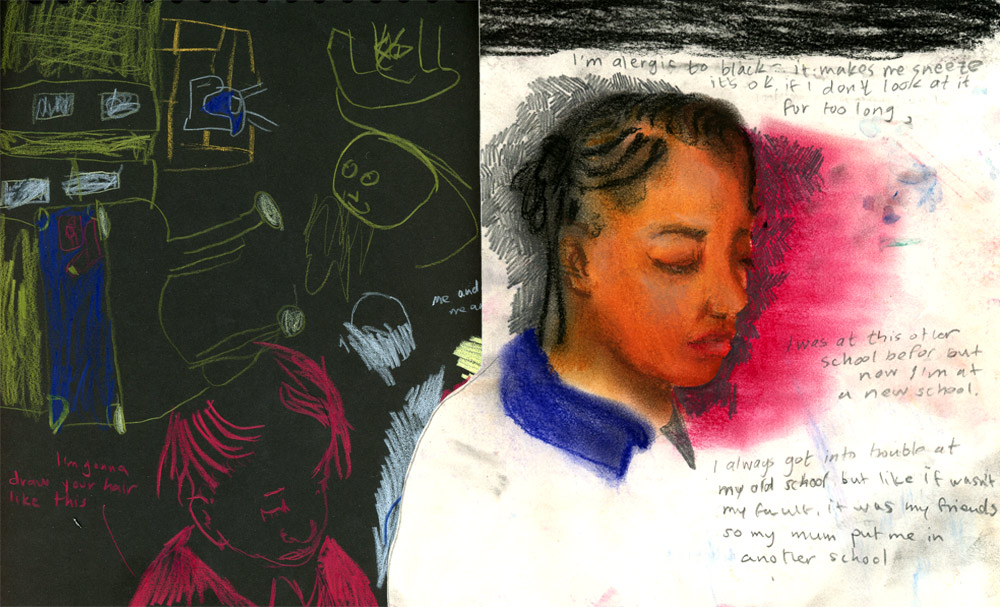

When I was eleven my biggest issues were; did I occupy too much space? And, would my breasts ever grow? Growing up in a white middle-class area in Sweden, I rarely had to consider the behaviour of government, an institution that seemed to me detached from my immediate life. I remember a hazy notion that the state was a safety net for when things went badly. But that’s it. Most pressing for 11-year-old me was, will the cool girls say hi to me if I wear these flailed jeans?To explore how austerity affects young people today, through my illustrations, I returned to the bubble of being eleven-years-old. Going to a youth club in North Peckham is the first time I have spent any significant time with pubescent and pre-pubescent kids since I was that age myself.

The youth club runs daily programmes for four to 10-year-olds in the afternoon and 11 to 14-year-olds in the evening. Here I meet a handful of the 3.5 million children that are living in poverty in the UK today. More than one in four children in the UK lives in poverty, according to the Child Poverty Action Group (CPAG).

Alan Milburn, former Labour MP and head of the Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission called the government’s latest strategy for reducing child poverty by 2020 “a farce”, and in need of “a major revamp to make it credible”. The government has also been criticised for ignoring the impact of the welfare cuts on child poverty, even though CPAG estimates the number of children living below the poverty line will rise to 4.7 million by 2020 if austerity continues.

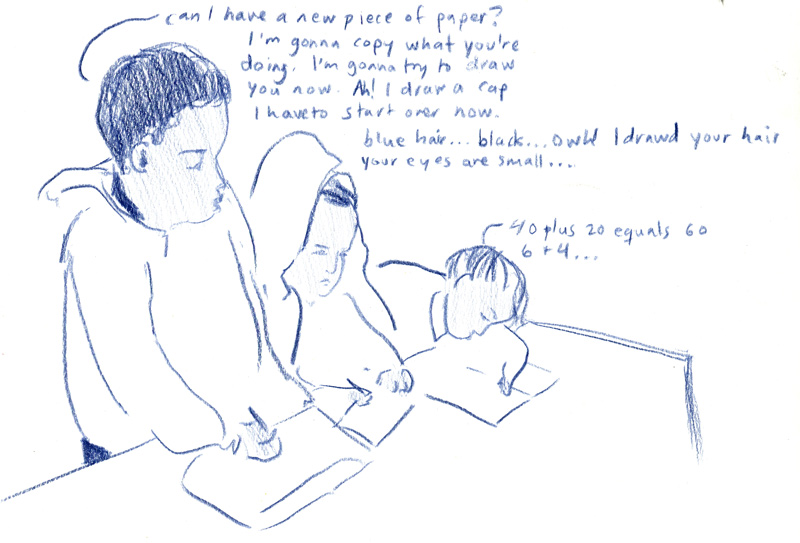

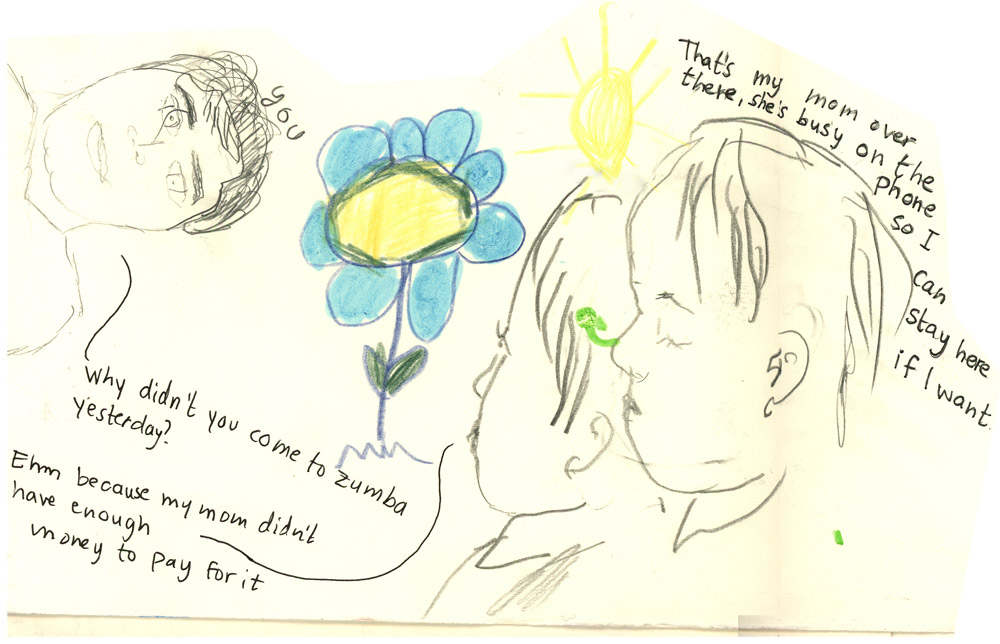

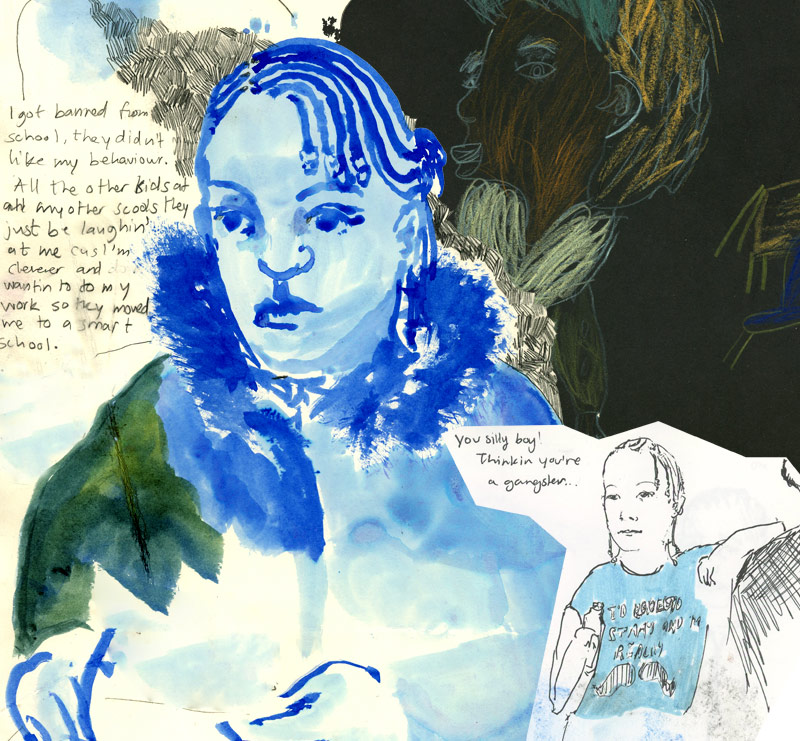

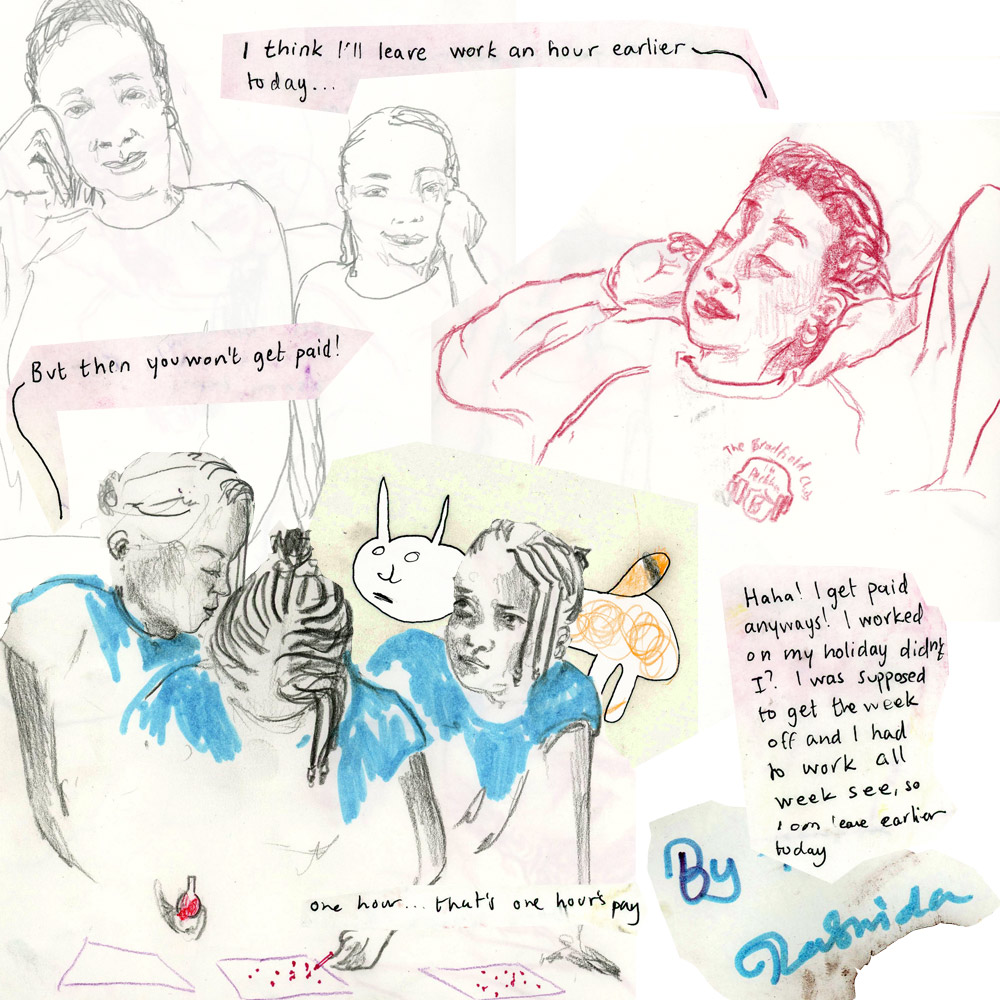

I arrive at 5.45pm to attend the 11-14 session. As the children slowly drop in one after the other, I immediately recognize the universal childhood cliques. I recognize the insecure movements of the self-conscious, something I was so painfully a victim of at that age. There is only one other girl in the room. She looks bored, circles the room a few times, before glancing over to see what I’m doing. I ask if she wants to draw with me. Her name is Rasheeda and she’s 10. She lets me beat her at fussball, since it’s my first time playing, but shows no mercy in the 10-2 rematch.

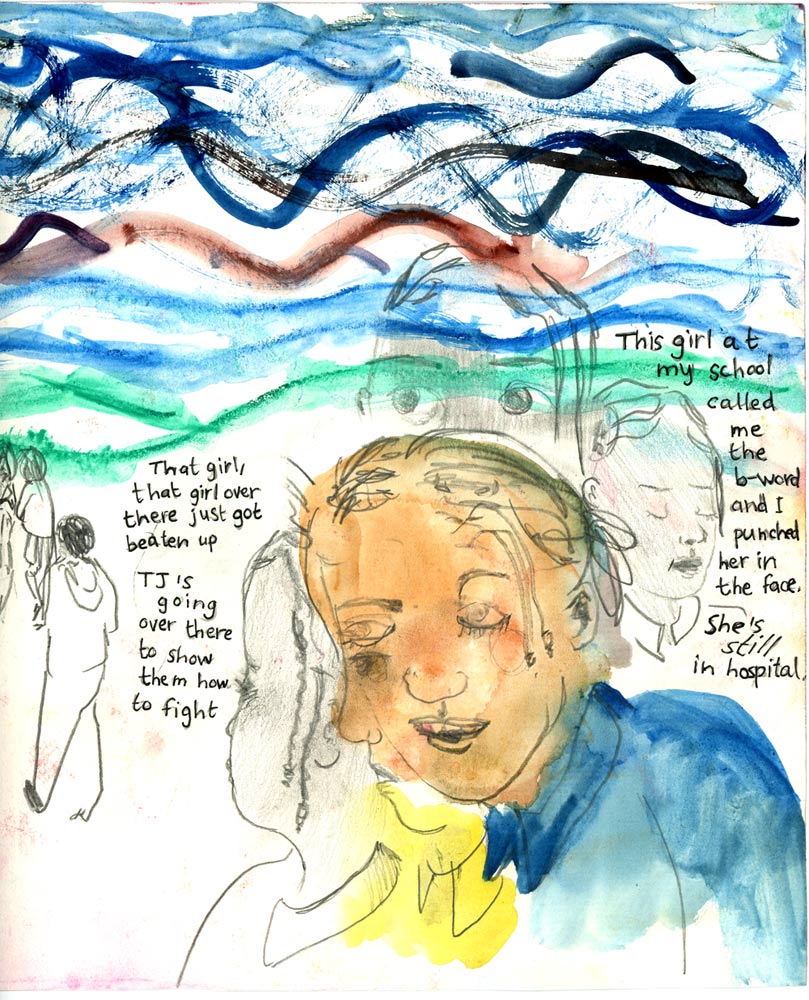

Only the next day, after I score a 4-pointer in basketball, does Rasheeda decide I’ve passed the test, and that we’re officially friends. I’m relieved and giddy and feel a return of the prepubescent excitement and pride that only comes with social acceptance. She lets me in on the gossip at the youth club, points to a group of older girls standing just outside entrance and tells me that one of them was hit in a fight and now they’re planning revenge. She lets out an excited “ooooh” as one of the boys walks up to the group. “T.J’s gonna show them how to fight,” she tells me.

It’s 5.45pm, two weeks later. I walk into the youth club and something is wrong. The kids are all outside, the atmosphere is tense. One of the youth workers, Daniel, pulls me aside and tells me they got a call from a passer-by saying she saw some of the boys passing around a knife. Not a small pocket-knife, a weapon. I’m stunned, the oldest kid I can see must be barely 13; there must be some mistake.

After talking to all the boys separately, Daniel tells me to act good-cop bad-cop with him. He brings me and the two boys responsible to the back room. They stand awkwardly in silence and shrug as Daniel asks them questions, eyes darting around the room, avoiding our faces. All I can think about is how incredibly young they look, and how bad they are at lying. I recognize myself in them, the body language you think will make you look innocent, clueless; the fidgeting because your heart is racing from lying to an adult. At 12 the only lies I told were about homework.

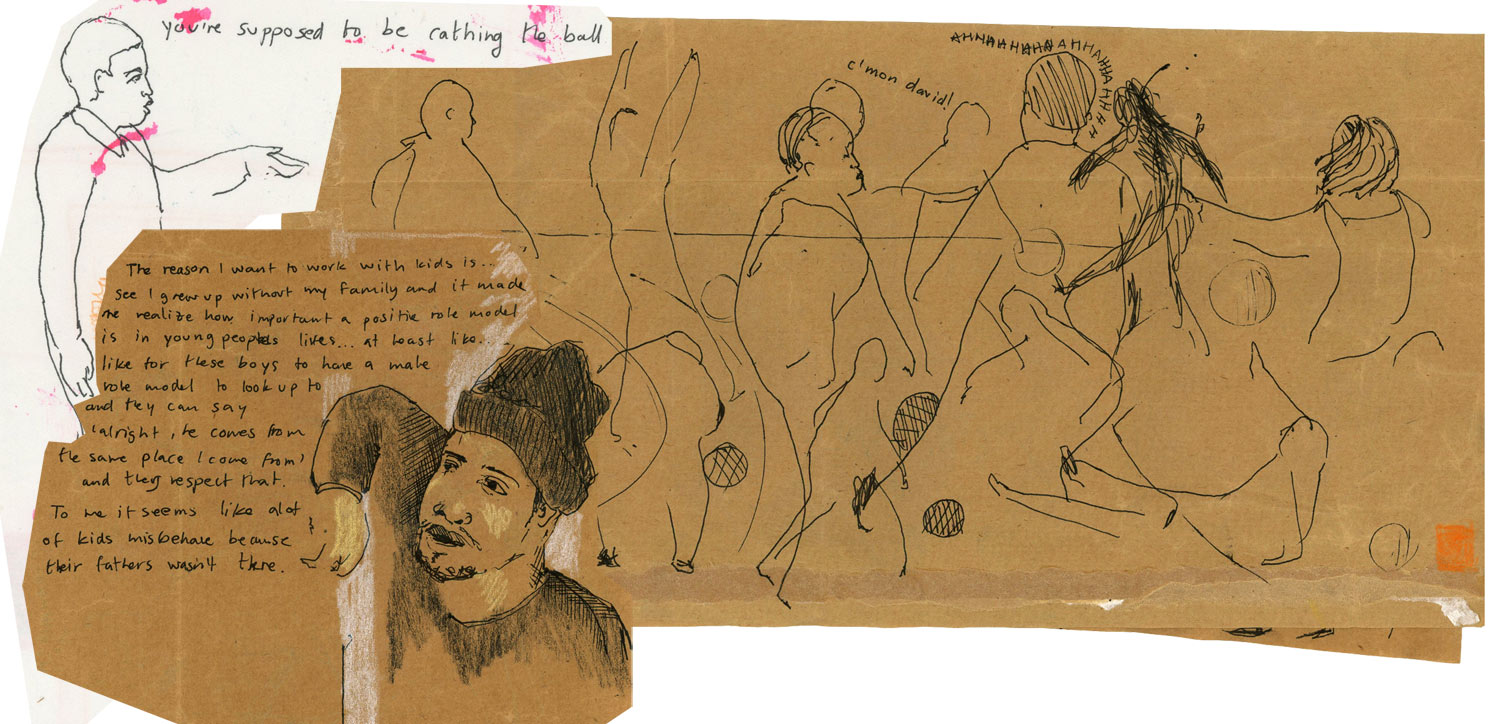

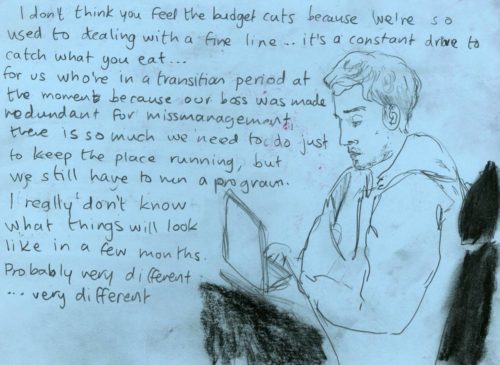

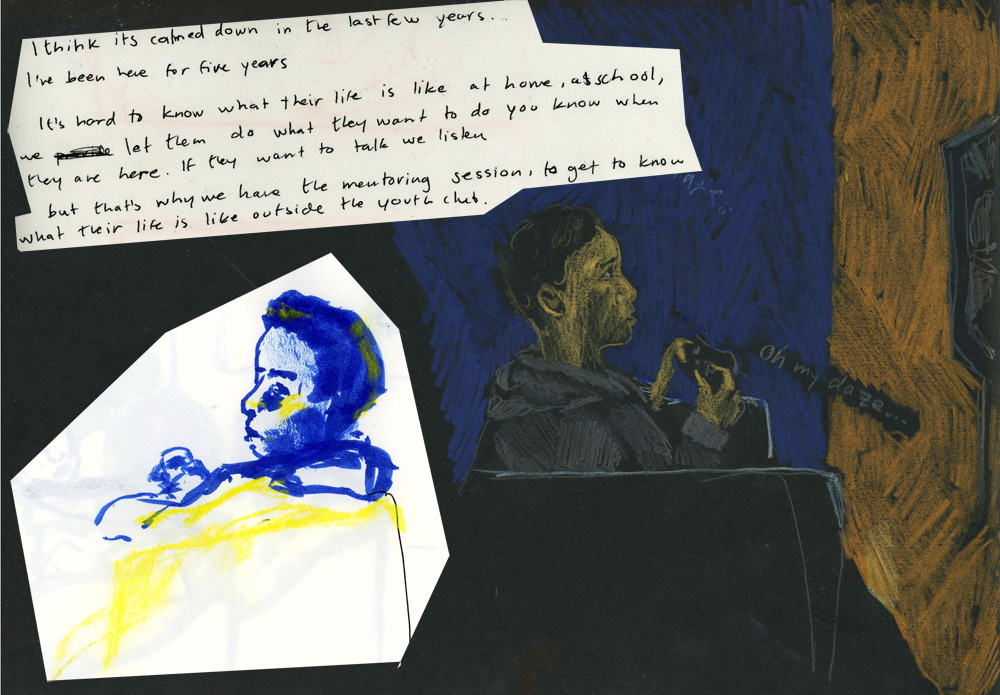

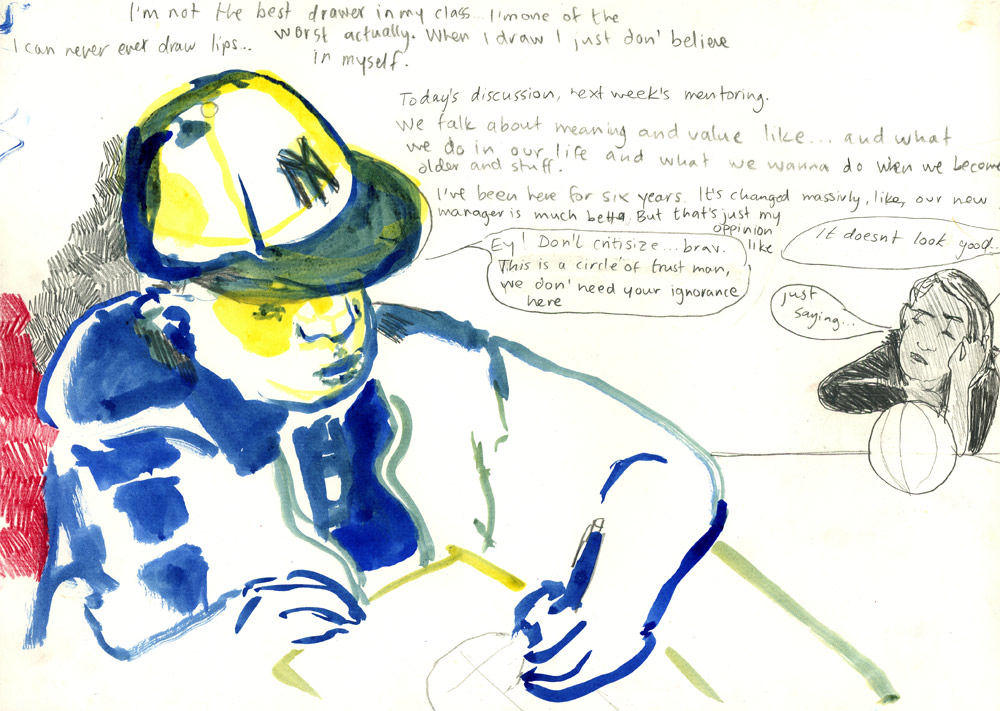

Afterwards, I sit next to Daniel as he fills out the incident report. He’s exasperated, there is only so much he can do when resources allow him only two hours a day with this age group. He tells me about the two boys we just saw. They have older brothers in gangs, how they look up to them. Once when he was having a mentoring session with one of the boys, he found out that a neighbour had offered the child £10 a week to stash crack in his room. A friend of Daniel’s did seven years for possession. Daniel tells me about his own past: “Nothing I’m proud of, but everyone has a story.”

A poster on the wall encourages the kids to “choose life, not the knife”.

But the reality is that the most immediate support system available to these children is the gang their older brother is in, the neighbour who will give them cash to carry out his drug deal. Social acceptance is as important for these kids as it was for me at that age, but the environment they want to be accepted into is vastly different. Whether they can describe what the austerity plan is or not, they are acutely aware of it’s consequences. And they are acutely aware of what little worth they hold as citizens in the eyes of the government. When the government cuts funding of the support systems for its most vulnerable citizens, it also fails to provide them with the option to choose life instead of the knife.