After her last column on LGBT acceptance in schools was quoted in Parliament, Deenah al-Aqsa returns to reflect on a spate of homophobic hate crimes perpetrated by young people.

Like many LGBT people across the UK, this year’s spate of homophobic attacks has left me hurting. It’s also forced me to reflect on my past, as I’ve noticed a worrying pattern with these incidents – the involvement of young people. And I’m questioning what this means for public perception of teens, and of teenage boys in particular.

The highly publicised incident of the female couple on a London bus who were assaulted by a group of teenagers, the boys that pelted stones in Southampton at actors who were starring in acclaimed play Rotterdam and the two men in Merseyside who were victims of a homophobic knife attack by three young boys are still weighing heavily on my mind.

More recently a man in southeast London was slashed with a machete in a suspected homophobic assault; another was punched and left unconscious in Upminster while travelling with his partner; a woman in Hull was targeted in a suspected homophobic attack that led to facial injuries.

As a queer person, there is even more insult added to the injuries sustained because all of these incidents happened during Pride season, a time of year intended for the celebration of our identities.

Instead, it was a time when those who were out and visible – brave in a way I don’t think I could ever be – were forced to see how terrible the world has become (or, perhaps it always was). In the process, those like me, who take refuge in the closet, see stories like these as cautionary tales. Each headline is yet another reason for us to barricade ourselves in this suffocating space that is nevertheless safer than being out and open to attack.

Read more: Six survivors remember Spain’s brutal anti-LGBT laws

When seeing these stories hit the headlines, I noticed that most of the attacks were carried out by teens. Recent reports indicate a disturbing trend of homophobic and transphobic hate crimes perpetrated by young people – and often to young people. I believe that prejudice and bigotry are taught and learnt, rather than inherent in a person. Young people follow the examples of those around them. They seek to emulate their peers and those they look up to via microaggressions and the casual use of slurs – behaviour that then becomes normalised and escalates to something more extreme.

For instance, growing up, I had heard of trans people, but only ever referred to as “tr*nnies”, not real women or men. Teenage me had no idea that being non-binary was even a thing, but I strongly suspect she would have joined those around her in dismissing anyone requesting specific pronouns.

When I first came across the concept of women being attracted to women, I was 10 years old, and it was entirely through terms like “homos”, “lezzies” and “dykes”. The single-sex school I attended was infamous for being “full of lesbians”, despite the fact that in my five years attending that school I only encountered two girls who I knew identified as such. In other words, my only knowledge of people not identifying as cisgender and heterosexual was through derogatory words that othered them, labelling them abnormal and unworthy of respect.

I imbibed a great deal of prejudice in my school years. Still today I am working to unlearn that prejudice, against myself and others in my community.

I don’t believe the young people behind several of the recent homophobic attacks were driven to do these horrific things because of an overnight change of mind, because just like my process of acceptance is an ongoing journey, not a fixed destination, so too is the polar opposite. Those young people did what they did because of intolerance they learned and witnessed over time. It’s likely this included the kind of slurs I encountered as a child and still come across to this day – and worse.

There is also a trend of less noticeable homophobia among young people that is, while not particularly subtle, often perceived as harmless by society. The social media trend of adding “No homo” after compliments to assert the speaker’s straightness was at its height when I was at school. Even among friends, people went to great lengths not to be seen as gay. Aged 14, my female friend came out to me as pansexual and my immediate reaction was to remind her that I was straight. It was as if her attraction to girls meant she had to be attracted to me by default. I found myself doing a verbal “no homo”, because I felt threatened by gayness too.

But I grew and I learned. Aged 13, I would repeat the deluded mantra of “Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve” as if that was actually an intelligent point. At 15, in a religious studies class, I was discussing the EastEnders character Syed Masood being both Muslim and gay, trying my utmost to vocalise why I had such a problem with it because of religion. But claiming religious observance as the basis for judging the morality of a soap opera, of all things, seems in hindsight downright preposterous.

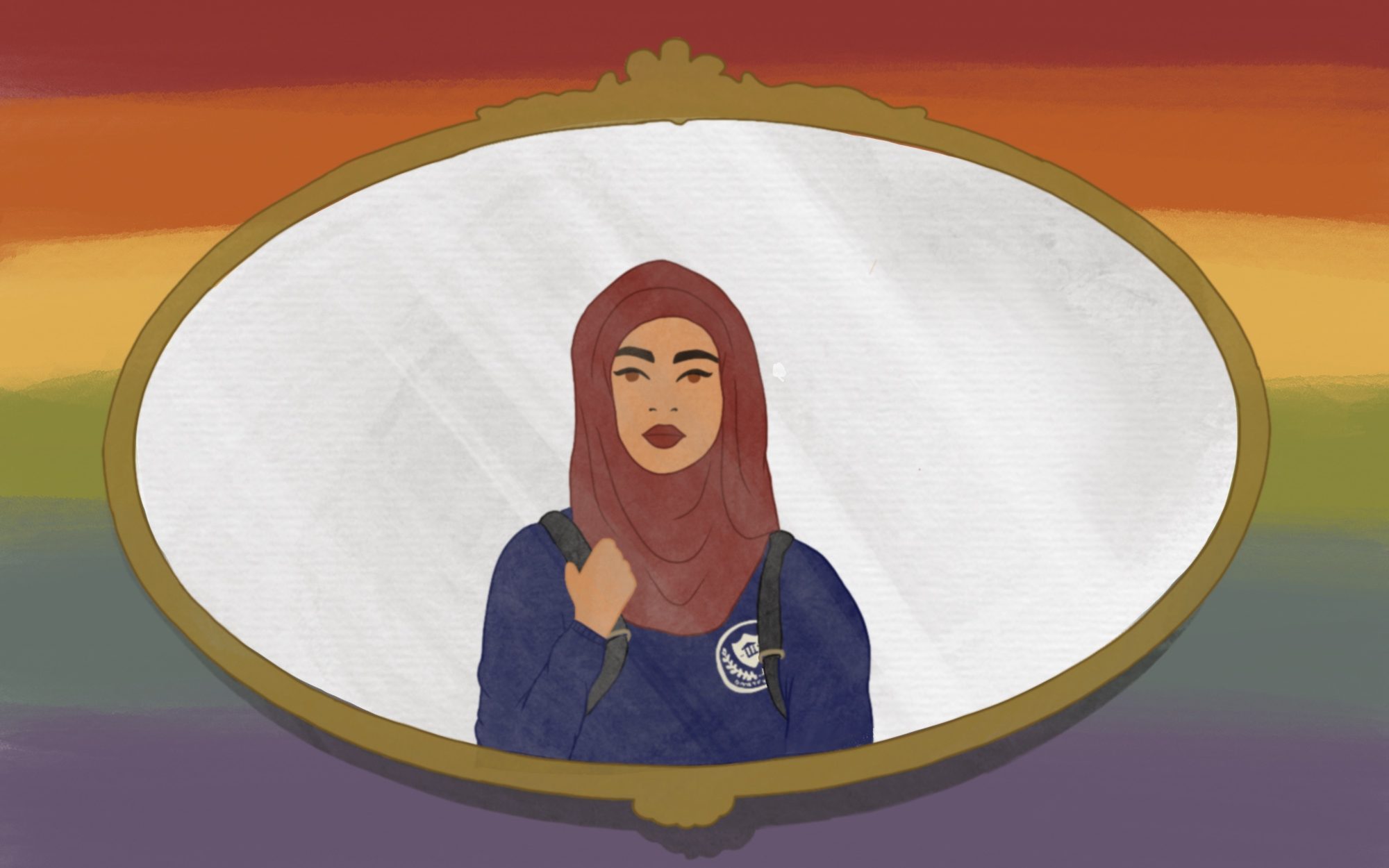

If I could go back in time and tell my teenage self that the source of my problem was staring back at me from the mirror every morning, I wonder if I wouldn’t be a very different person today.

It took time. I was still calling myself straight aged 18. I used to recoil at the word “lesbian” because its connotations had never been remotely positive to me, which is why I only started using the lesbian label a year ago. So far, the vast majority of the times I’ve used it is on equal opportunities forms. It’s a small thing, but I feel more like me than I ever have when I tick that box, knowing it’s now my normal.

It takes time to get used to that normal, though. There’s still a moment of shock the few times I see a couple of men holding hands on the train or a woman in a salon casually mention her wife. But it’s now followed with a smile or nod, a shared moment of unrivalled queer understanding that I’ll never get enough of – because I’ve managed to get there.

As with many things, then, surely being tolerant and accepting of something that is perceived to be different isn’t binary in nature. It’s not just the things that make the headlines that matter. Nothing is ever a case of one thing or another, black or white, starkly violent hate crimes during Pride versus exuberant rainbow flags. There is room in between that needs to be acknowledged too – a space to come to compromises and learn how we can do right by people who need recognition, now more than ever.

Read more: Football fans unite against fascism and the rise of the far right

Every journey has a starting point, and this may involve confronting and questioning your core values. Political figures are a prime example of people who can be seen to change their position on seemingly immovable issues with time. At one point much earlier in her political career, former Prime Minister Theresa May, now a self-styled life-long LGBT ally, voted against legislation in Parliament that would have furthered the LGBT community and our rights. Later, she claimed her views had evolved over time, to the point that she said she would have voted differently if she were given the opportunity to again. Whether this change was political or personal, we can’t know, but either way it could only come about with time and room for discussion, re-evaluation and moderation.

I want the young people of the next generation to be allowed the space to talk openly about these issues. I don’t want us to be frozen in my time, not so long ago, when the LGBT community were sniggered at the few times they were mentioned in class, spoken about in whispers behind hands as something lewd and only ever the subject of ill-gotten humour or ridicule.

Earlier this year, new government guidelines were issued for primary and secondary school students on sex and relationships education. And though in my view they should have been reviewed much sooner (given the last review took place in 2000), I hope this will allow students to discuss these things and ask questions I didn’t feel able to.

The guidance issued is just that – guidance, and therefore something schools can depart from with “good reasons”. However, being conscious and inclusive of LGBT issues is a definite step in the right direction, irrespective of how big that step is.

I was glad to read, for instance, that the guidelines stipulated the importance of not having standalone lessons or modules for LGBT matters. My hope is that schools will adhere to the guidelines advising them to integrate LGBT issues into the framework more holistically. This way, those children who are perhaps questioning their gender identities or sexual orientations will feel less othered than I did when going through a similar struggle.

Ideally it makes more sense to have this set in stone, in legislation that schools have no choice but to adhere to. Equally, however, perhaps this is what is needed – the space to learn and grow, and to come to compromises, on the parts of the teachers and the students. Maybe then we can move towards changing the views of young people, who may be tarred with the same brush as those in the headlines committing hate crimes. Only then can we stop this cycle of hatred my generation were also stuck in.

Speaking from personal experience in the closet, I know that Pride next year won’t outwardly be that different to me, as I’ve never attended a parade myself. But it is my sincerest hope that this time next year, those courageous enough to celebrate can do so more freely. I’d like to believe that when Pride comes around again, I’ll be able to go back to living vicariously through my queer friends who I hope will be celebrating, rather than tending to each other’s wounds.

Art by Kassidy Dawn.