After touring the US to speak with the families of people shot dead by police, criminology lecturer David Baker shares his findings, including one relative’s warning: “If you love someone and don’t want to lose them don’t call 911.”

Daniel Ficker was 27 years old when he was shot dead by police officer Mathew Craska in Parma, Michigan on 4 July in 2011. Accompanying Craska was an off-duty officer (David Mindek). Both were outside their area of legal jurisdiction. Neither were police officers in the City of Parma Police Department, but from nearby Cleveland.

Daniel had returned home with his partner to find the two officers waiting in a cruiser outside. He’d been at a party the previous day thrown by Mindek’s wife. She believed that some of her jewellery had been stolen, and suspected Daniel as the thief.

Mindek accused Daniel of stealing the jewellery, Daniel denied it, and Craska attempted to arrest Daniel and force him into the cruiser. He resisted the arrest, shouting for neighbours to call local police to intervene – without success.

The two grappled in Daniel’s front garden and in the ensuing struggle Craska initially fired a TASER at Daniel and then fatally shot him using his service weapon.

Daniel left behind two children aged five and seven. His mother – Bernie Rolen – told me the two officers involved were put on administrative leave during the investigation into Daniel’s death. Once the investigation was complete, the shooting was deemed to be “justified”, and the officers returned to work. Bernie told me:

What boggles my mind is that everybody knows they were wrong and yet they are free.”

Last year, a total of 39,773 people were shot dead in the US – that’s nearly 108 killings a day.

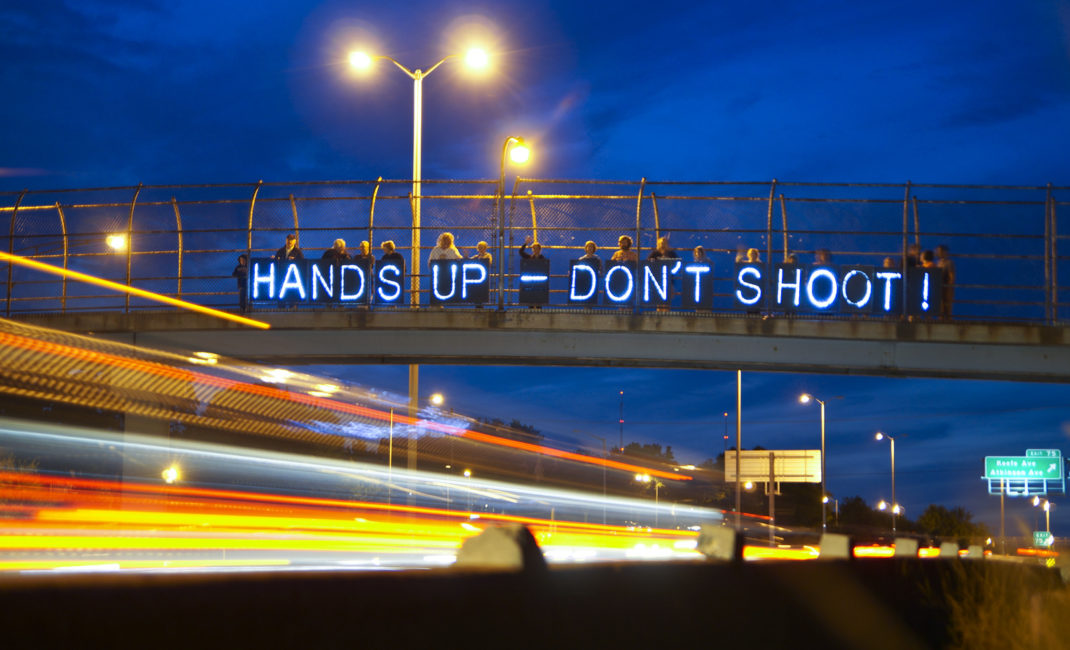

People in protest against the shooting of Mike Brown in Ferguson. Picture by Joe Brusky

According to the New York Times in 2016, that amounted to 31 deaths per million across the country. By contrast, only one person per million was shot and killed during the same period in England and Wales.

The huge numbers of fatal shootings might explain why US authorities have failed to count officially the number of citizens killed by the police, a fact the FBI director admitted was “embarrassing”. This came to light in the aftermath of Mike Brown’s death in Ferguson in 2014.

Black Lives matter rally following the grand jury decision in the case of Mike Brown in Ferguson. Picture by Fibonacci Blue

He was an African-American shot dead in contested circumstances by a white police officer who was later cleared of any wrong-doing. The incident became a catalyst for the Black Lives Matter movement who used it to highlight not only the systemic nature of such deaths but also the heavy-handed police response to peaceful protests, which included firing tear gas and water cannon at demonstrators.

In the aftermath of this, The Guardian built an interactive website called ‘The Counted’. It constructed the first verifiable data of killings in 2015 and 2016, which the FBI and US Department of Justice have acknowledged as being accurate. We now know that 1,115 citizens (about three per day) were killed by police annually during that period.

But is this number so surprising in a country where deaths by shooting are so normal? After all, out of 39,993 killings, 1,115 might not seem so extraordinary in such a violent society.

Deaths after police contact in the US are typically the result of fatal shootings, and many of these are routine encounters that escalate. But a significant number of the people killed are not violent or engaged in criminal activity at the time of the incident.

The deaths are distributed disproportionately – if you are on the margins of society you are more likely to die. Native Americans are the most disproportionately affected, being three times more likely to be killed by police than white citizens.

African-Americans are killed at double the rate of white Americans. And if you have mental health issues, you are also more likely to die as a result of an interaction with the police. But the stories behind these statistics are difficult to uncover.

To find out more, I carried out a research project in 16 states across the US in 2016 when I interviewed the relatives of 43 people shot dead by police since 2000. I’d previously researched deaths after police contact in the UK and was aware of developments in the US.

Read more: Walking the migrant trail from Mexico to the US across Trump’s proposed border wall

It was The Guardian’s ‘The Counted’ project that convinced me of the need to look behind the numbers and investigate the human and social costs of these deaths to the families and loved ones left behind.

I interviewed families on the west and east coasts; in the deep south and midwest; in large cities, small towns, and rural areas; and repeatedly heard harrowing and traumatic stories of ordinary American citizens whose lives had been taken by police. They were male, female and transgender; of various ethnicities; old and young, rich and poor; and of a variety of sexualities.

A protest in San Francisco after police shot and killed police shooting of Kenneth Wade Harding. Picture by Steve Rhodes

The interviews revealed a remarkably consistent number of themes. Police were viewed as a paramilitary force, adopting a ‘comply or die’ mentality.

Relatives of the deceased believed police to be increasingly fearful of the citizens they were sworn to serve and protect, and more focused on their own personal safety than that of citizens. This led to an ‘us or them’ outlook that seems a long way from a consensual model of democratic policing.

In the aftermath of a shooting, relatives were also unanimous in stating that no accountability was provided by criminal justice agencies, reinforcing the feeling that the death of their loved one didn’t matter, that these shootings were “normal”.

Typically, police internal affairs units investigate such deaths. Their report is passed to a District Attorney (DA) who determines whether there is a case for the officer to answer. It is rare that officers are indicted as a result of the DA’s decision, and extremely rare for a criminal case to be brought successfully against officers as a result.

Read more: Carlington Spencer – Another death in UK immigration detention

There is a widespread perception that not only are officers using lethal force in an unaccountable way, but that they’re doing so within a justice system that enables its use. It’s perhaps no surprise then, that the lack of transparency and accountability in both police agencies and wider criminal justice organisations has created a sort of existential crisis for the relatives of loved ones killed by police.

Their experiences of police and the justice system were entirely at odds with their expectations. Police were viewed as purveyors of injustice.

One family member told me: “Whenever there’s an issue in your family, please don’t call the cops, because nine times out of ten, your loved one will end up killed.” Another said: “I tell people – if you love someone and don’t want to lose them don’t call 911.”

A march in New York against police brutality. By The All-Nite Images

If police were viewed as purveyors of injustice, then criminal justice agencies were seen to reinforce this injustice. I was told time and again of how the official investigation into killings produced no resolution satisfactory to the relatives. Perhaps this was unlikely anyway. As one family member told me: ‘We had the police working against us because it was the police that did this.’

As with most shootings in the US, deaths after police contact are often presented as individual cases. But they’re better understood as a systemic organisational practice. The lack of accountability is also systemic.

But in a country where 108 people per day are killed by guns, those three per day killed by police hardly register. When criminal justice agencies uniformly endorse these deaths as ‘justifiable’ they are contributing to a culture of normalisation and acceptance.

Daniel Ficker was pronounced dead on Independence Day, 2011. In the aftermath of Daniel’s killing, his mother sometimes saw officer David Mindek on patrol – she worked near his beat area.

The subsequent police investigation into the jewellery Daniel was alleged to have stolen found no evidential trace of him in the room where it was stored, or on the box in which it lay. Both officers were exonerated of any wrong-doing and have now left the police force.

After nearly six years of fighting for justice, Daniel’s family were granted a financial settlement of $2.25 million in a civil suit which would provide for his children’s future. Many of the families I met told me “we’ve come to realise these killings are business as usual”; before noting “we’re sick of business as usual”.

For Daniel’s family, July 4th now has a different meaning, it marks a time when their belief in justice and accountability in the US changed forever.

Main image shows man protesting after police shot dead unarmed African American Oscar Grant. By Thomas Hawk.

- For content like this direct to your inbox, subscribe here.