Born in Bournemouth, England in 1965, Kimathi Donkor is a contemporary visual artist based in London. His paintings, described by reviewers as ‘vivid’, ‘deeply poignant’ and ‘striking for their overt political content’, have been exhibited internationally in Johannesburg, Lisbon, Rome, and São Paulo in Brazil, as well as in the UK, including London, where he has held several solo exhibitions. Donkor has engaged with questions of human rights as an artist, an educator and, earlier in his life, as a community activist.

Philip Kaisary: Thank you, Kimathi, for agreeing to speak with me today about your work. I wanted to begin by asking you to talk a little bit about your background and how your artistic vision emerges from this?

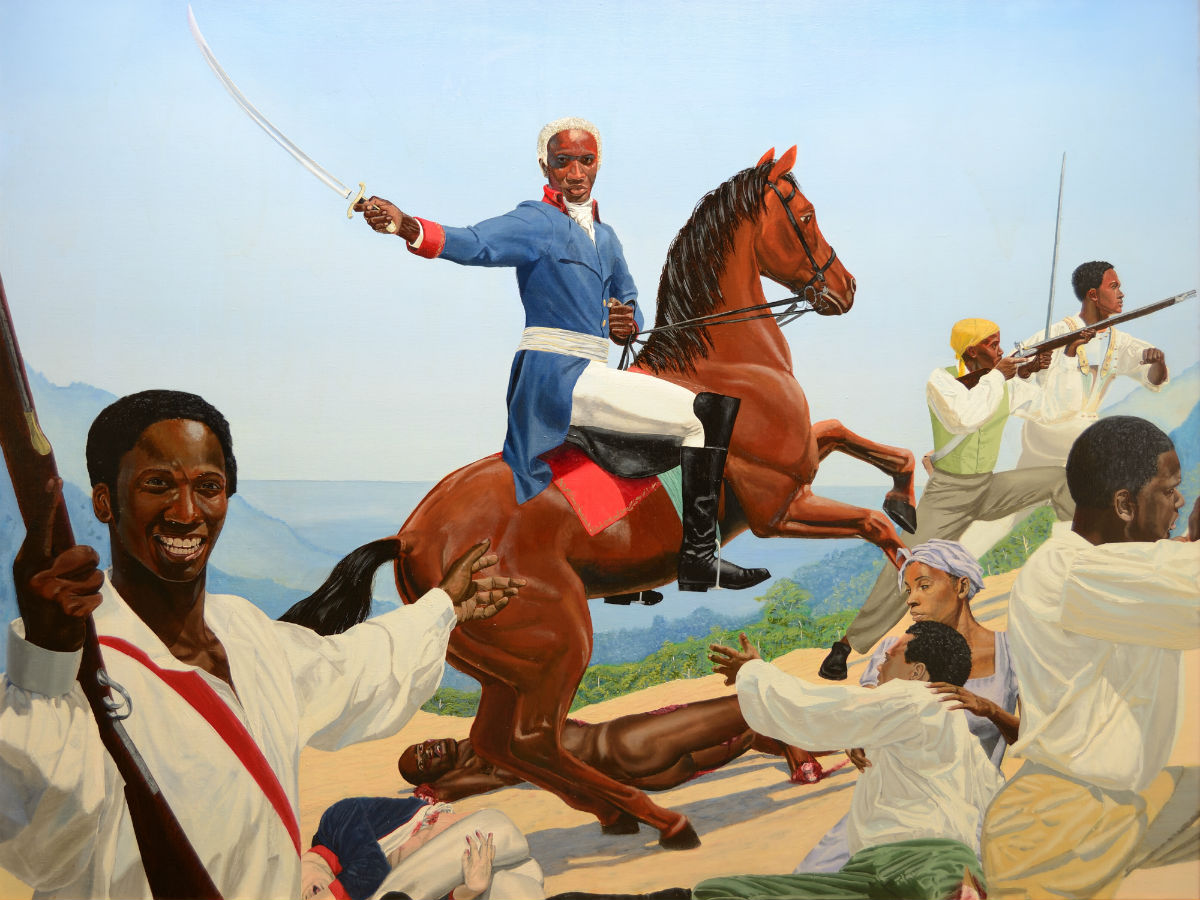

Kimathi Donkor: Thanks for talking to me, Philip. I was born in the UK to an Anglo-Jewish mother and Ghanaian father, but was raised by my adopted parents who were from Jamaica and the UK. We lived for a time in Zambia, Central Africa, where my adopted dad worked as a vet. I finished my schooling in the west of England, then moved to London, where I eventually settled. In the meantime, my adopted parents had divorced and remarried, so the family diversity actually increased, as Zambians also joined the party. This smörgåsbord life induced an early sense of the wondrous, and sometimes maddening, complexity of identities and histories, which, I think, has been reflected in my artworks. Precisely because I was such an intimate witness to the multiple crossings and re-crossings of stories, images and journeys from around the world. Perhaps an example of that narrative entanglement could be seen in ‘Toussaint L’Ouverture at Bedourete’, which represented figures constructed as being from Africa and Europe as they struggled for control of Hispaniola, a Caribbean island previously settled by the Taino people. In order to effect that sense of struggle, I used conventions I had sourced from the art of modern Haiti and Ancient Egypt, as well as post-revolutionary France. So, I intended the painting to produce for the viewer a metaphorical whirlpool of transnational, intersectional, artistic and historical references, which were then suspended in perpetual, dynamic tension by the composition itself.

This smörgåsbord life induced an early sense of the wondrous, and sometimes maddening, complexity of identities and histories, which, I think, has been reflected in my artworks.

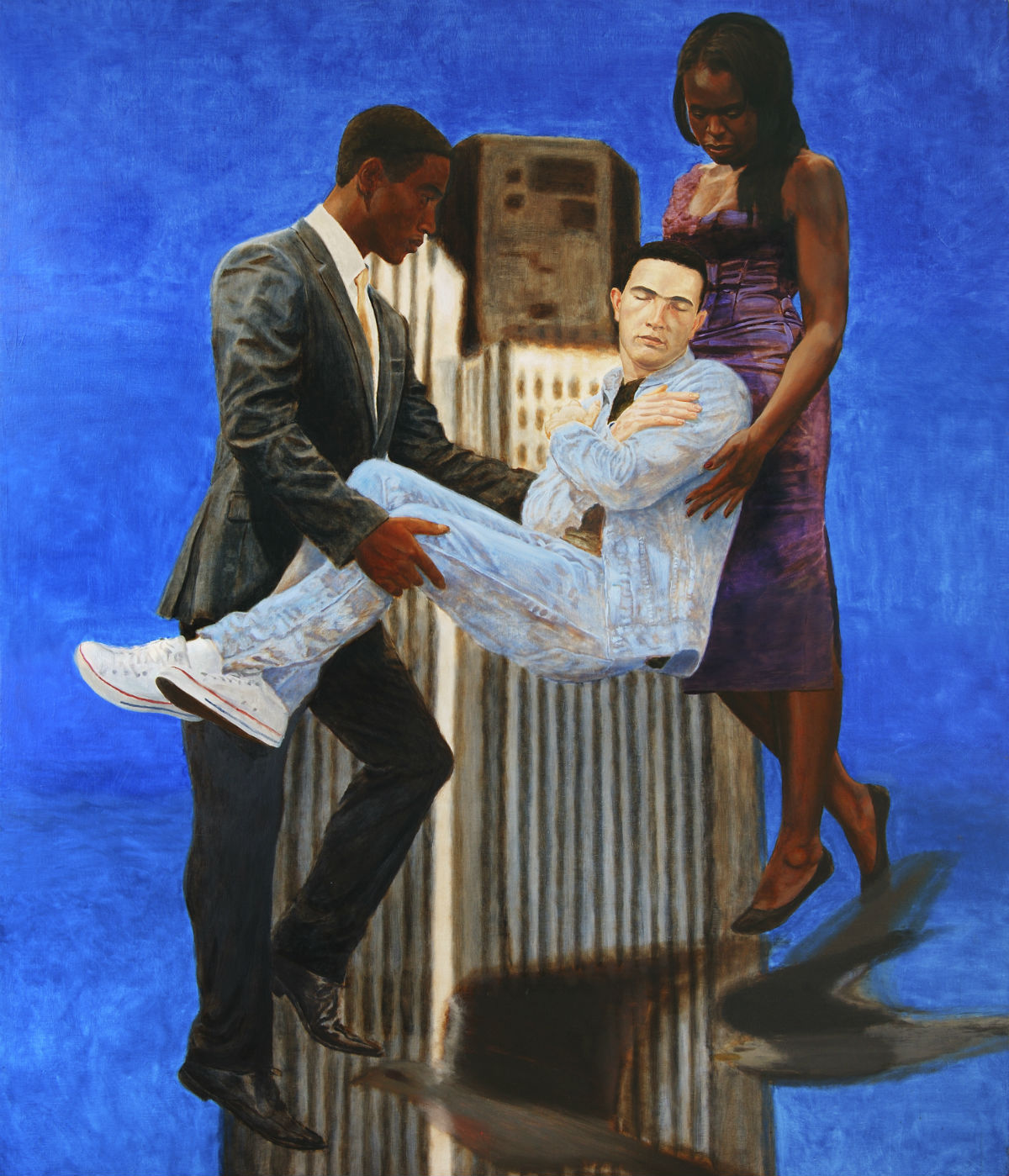

PK: You were a community activist and human rights campaigner for many years, and one theme that recurs throughout your work is the fact of police brutality inflicted on London’s black and immigrant communities. I am thinking here particularly of your painting ‘Jean Charles de Menezes borne aloft by Joy Gardner and Stephen Lawrence (Johnny Was)’, as well as paintings such as ‘Under Fire: the shooting of Cherry Groce’ and ‘Helping with enquiries’. How does your experience of activism relate to your artworks? Do you see yourself as a human rights artist? As a didactic artist? How do you see the relationship between art and social justice?

Helping With Enquiries: 1984

KD: That’s an intriguing question. Although I haven’t been a proper activist, I have been an independent community organiser for fifteen years. I certainly don’t believe that my paintings should, or could, ‘convince’ viewers about one or another political perspective. Rather, those disturbing, reimagined narratives were intended as an artistic starting point from which I tried to consider certain psychological and aesthetic enigmas. Perhaps they even represented attempts at self-healing. During the eighties and nineties, starting from when I was an undergraduate art student at Goldsmiths College in south London, I did collaborate formally with a number of community organisations and amongst other activities. I put to use my somewhat meagre talents as a designer, producing flyers, pamphlets and the like. At first, I used a rough-and-ready, handcrafted aesthetic for a group calling itself the ‘Black People’s Campaign for Justice’. I made flyers that expressed solidarity for people unjustly targeted by the state – such as Cherry Groce, an unarmed, entirely innocent woman who, in 1985, was shot and paralysed in her home by a police officer during a botched raid. Then, as digital technologies became cheaper and more widely available, I experimented with what we used to call ‘desktop publishing’. The community organisation needed more sophisticated design and print techniques, the sort that had once been the preserve of well-resourced corporations. This allowed us to produce a more polished aesthetic. I took an evening course with the London School of Printing to get a better grasp of design and publishing.

In later years, I struggled to reconcile the communal processes of activism with the need to develop a coherent, artistic vision. So I think my ‘Jean Charles’ painting, which was commissioned in 2010 by the 29th São Paulo Biennial in Brazil, addressed my own relationship with a trio of human rights tragedies. Joy Gardner and Stephen Lawrence had both been killed in London in 1993, Ms Gardner by police officers attempting to deport her to Jamaica, and the 18-year-old student, Stephen, by a gang of racists who were later videoed making violent threats against people of colour. At the time, I joined demonstrations and other campaign activities, such as attending the trial of Ms Gardner’s alleged killers. And the Lawrence case – before some of his killers were convicted after eighteen years of impunity – forced the Metropolitan Police to denounce its own ‘institutional racism’.

Jean Charles de Menezes borne aloft

by Joy Gardner and Stephen Lawrence

By 2005, when the Brazilian electrician, Jean Charles de Menezes, was shot by police on a crowded commuter train – having been mistaken for a suicide bomber in the wake of the horrific 7/7 bombings – I had not been an activist for five years. I still felt, as well as compassion, a sense of proximity, and perhaps that was inevitable. Not only was there the disheartening coincidence that, when I heard the first radio reports about Jean Charles I was quite literally working on my Cherry Groce painting; but also, and even more disturbingly, was the fact that, like Mrs Groce, de Menezes had lived in my neighbourhood. When police, secret police and soldiers are hunting a fugitive who, arguably, looks a bit like you, and then they shoot an innocent person – well, the implications are bound to be disconcerting.

This imagery did not mean I had withdrawn from a concern with the intricate mechanisms of society, or from politics, but that my reflections of that concern had become more meditative and introspective.

Yet, outside of a formal, organising structure, I no longer had that earlier compulsion of duty: the sense that it was my immediate responsibility to produce protest. Instead, I began to document and to study, but with artistic priorities to the fore. With a certain sense of trepidation, I photographed the taped off area near my home and, when I tried to photograph the entrance to the train station, a nervy policeman tried to stop me. Even after completing those initial acts of documentation, I still did not immediately produce a work for exhibition. It was only four years later, when the Biennial curators, Moacir dos Anjos and Sarat Maharaj, approached me, that I thought I had acquired enough critical distance to make a work appropriate to what I considered was at stake. Instead of revisiting the terrifying ‘execution’ trope that had been to the fore in my Cherry Groce and Cynthia Jarrett paintings, I attempted something that was just as compelling, visually: three, apparently weightless figures suspended in a blue empyrean. However, these new figures seemed to be resisting forces that appeared much less personal and more remote than an authoritarian employee with a badge or gun. The trio seemed, instead, to defy forces that were perhaps far more unrelenting and remorseless – without wishing to sound pretentious, I mean such forces as myth, power and mortality. Perhaps even nature itself, in the form of gravity. This imagery did not mean I had withdrawn from a concern with the intricate mechanisms of society, or from politics, but that my reflections of that concern had become more meditative and introspective. Perhaps it was an artwork that tried to address feelings of grief, compassion and hope, instead of the anger, fear and confrontation that were more apparent in the 2005 paintings.

Toussaint L’Ouverture at Bedourete

PK: Your paintings range across numerous subjects and themes, from history painting [in ‘Toussaint at Bedourette and ‘Harriet Tubman en route to Canada’], reworkings of neo-classical motifs [in ‘Nanny’s fifth act of mercy’], as well as the subject of contemporary police brutality, which we have already discussed. What connects these multiple projects – is it human rights? Race history? Colonial history and its legacies?

KD: Many of my figures and artistic appropriations are drawn from historic, or mythic, narratives and conventions that, arguably, might be characterised as ‘post-colonial’ encounters – many of which faced historic neglect in British art institutions shaped by imperial nostalgia. That is, my work is evoked by the kind of transnational entanglements that produced my own radically rhizomatic biography. In that respect, it is probably my own life experiences that, ultimately, join the dots between distinct works.

I think also that I was processing what the theorist, Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, has described as ‘intersectionality’ in discourse and community. As well as the subjects one has identified, such as race and colonialism, the very same artworks also addressed dilemmas and enigmas concerning aesthetics, gender, sexuality, class, and what we call the ‘environment’. By which I am thinking of our wanton destruction of, yet intense admiration for, this vast and magnificent planet. Certainly, the slightly older generation of black, London activists who I worked with in the eighties and nineties – such as the late Afruika Bantu (1955-1999) – were keen to discuss the philosophical implications of our interventions. Was race the central question facing post-colonial society, as proposed by the militant, African-Jamaican philosopher, Marcus Garvey? Or, alternatively, were class exploitation, gender inequality and imperialism the key causes of contemporary injustices? Afruika, whose untimely death in 1999 was a tragedy, seemed, in her fervent desire for social justice, to embody Brixton’s version of Eugene Delacroix’s famous 1830 Romantic painting, ‘Liberty leading the People’ (but without ‘accidentally’ losing her bra). Afruika was only one of several unsung women who acted as vivacious examples of the kind of passion and courage that had moved me to create paintings about historic, working class, black, female liberators – such as Nanny of the Maroons and Harriet Tubman. Somehow, despite our sometimes-profound differences in outlook, Afruika and I managed to cooperate in our work for more than a decade.

Harriet Tubman en route to Canada

So, Williams-Crenshaw’s insight about ‘intersectionality’ suggests to me that, as an artist, I can claim no insight about there being a single political, aesthetic, spiritual or technological key to the contemporary predicaments of oppression or inequality. Instead, I want to approach each distinct subject by asking how I can locate, within my own practice, an embodied sense of compassion and empathy.

From 26 February to 21 March, 2015, Kimathi Donkor will be Artist in Residence at the Gate Theatre, London, supported by the Chelsea Arts Club Trust.