Germany made headlines for receiving the most number of refugees in Europe during the recent refugee crisis. But how has both the state and civil society dealt with integration now and in the past, and what does this say about Germany’s future? Kim Harrisberg joined a group of journalists from around the world on an information tour run by the German Federal Foreign Office that focused on the complexities of immigration and integration in the country.

Oscar Wilde’s famous line, ‘Life is too short to learn German’, still brings knowing smiles to German faces. But for the near half a million refugees applying for refugee status in Germany amid the global refugee crisis, not learning the country’s language could mean a lifetime of marginalisation and hardship.

This is an all too well-known topic at Hunsruck Primary School in Kreuzberg, a district of West Berlin, Germany. Here, parents embrace their children as they run from the school gates with giddy excitement. Fingers are intertwined, bags are offloaded from small shoulders and dangling legs are lifted onto bicycle seats. Varied accents and languages mingle with the excited shouts, singing and laughter of primary school children released into the world after a long day of classes. Hunsruck Primary School is one of the estimated thirty schools offering ‘Welcome Classes’ to newly arrived refugees, predominantly from Syria, Iraq, Eritrea and Afghanistan. These classes offer a vital service across the country to refugees aspiring to embrace the language of their new and foreign home.

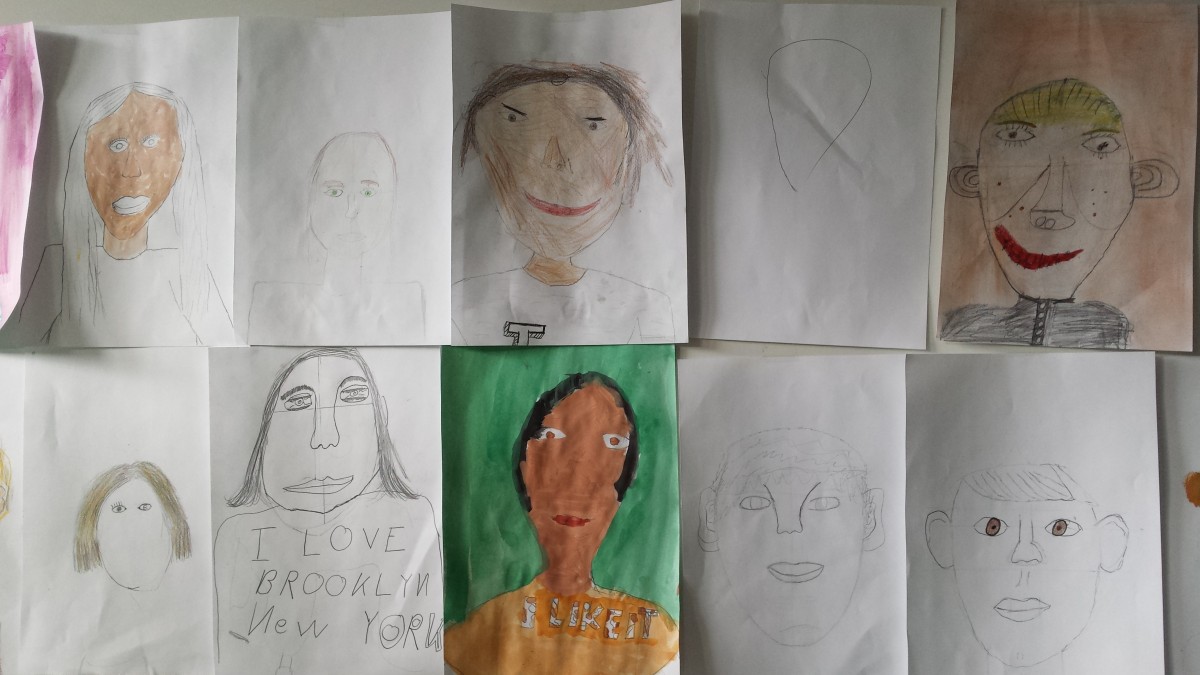

Self-portraits of the children from Hunsrück Primary School where many have a migration background.

“I don’t really like to call them ‘Welcome Classes’,” admits Frederike Terhechte-Mermeroglu, a teacher of 30 years who coordinates many of the classes. “In many ways, the refugees are still fleeing.” The school is meant to provide a transitional space for students who arrive in Germany after fleeing conflicts and urgently need to learn German, both to progress in school and to integrate into German society. It is not an easy process, largely due to underfunding, few teachers and even fewer translators.

These students are part of the one million refugees that recently crossed over Germany’s borders, and the 65 million displaced worldwide following conflicts predominantly in Syria, but also in political violence in Eritrea, Iraq and Afghanistan, among others. But migration is not a new topic within the country. According to the Expert Council of German Foundations on Integration and Migration, twenty percent of all Germans have a migration background. A guest worker agreement with Turkey in the 1960s and 70s saw numbers in the labour force rise according to Stephan Sievert, in his presentation on behalf of the Berlin Institute for Population and Development.

Understanding the statistics, and the stories behind them, are central to filtering through the stereotypes and debates surrounding migration and integration across the globe. This is relevant even in places like Hunsruck Primary School.

“The teachers are afraid…of what they do not know,” says Frederike, explaining that the starting and finishing times of the Welcome Classes are different to the rest of the school in order to avoid any conflict with the other students. She is sitting on a desk in one of the now empty classrooms. Self-portraits of the children decorate the walls, capturing the nuanced appearances of the diverse student body. It is this classroom, with German words scribbled on sheets of paper and the landmarks of Berlin up on a board, which captures the urgency of these classes in integrating the hundreds of thousands that are now a part of Germany’s society.

Nonetheless, Fredericke thinks it’s not enough. “We have one student who can never have his back to the door because he jumps every time someone enters the class. Some have never been inside a classroom before. Health insurance for the students does not cater for psychotherapy,” she explains. She seems jaded by the poor state response to the urgent needs of such Welcome Classes, yet believes that “the strongest of all are the children themselves”. It is this, and the prospect of the educated children being able to help their families and future generations in Germany, that pushes her through the more difficult moments.

Radical Voices and Civil Society’s Response

Some Germans do not feel the same way as Frederike. South of Berlin is the city of Dresden, capital of the Eastern State of Saxony. Among other things, it is home to the now rebuilt architecture of the 1700s that was destroyed during WWII. The right wing populist movement, Pegida (an acronym for the English translation of ‘Patriotic Europeans against the Islamization of the West’) has a strong presence here. The two are closely linked. The annual memorial of the city’s destruction in 1945 attracts many from the fascist network, which is one reason why Pegida has prevailed in Dresden while fizzling out in other cities.

The DDV Stadium in Dresden, home of the SG Dyamo Dresden football team. The team has a Syrian player who has been in Germany for many years.

“What is Pegida?” asks Professor Werner Patzelt, a political scientist at the Dresden Technical University and the author of a book on the organisation titled ‘Pegida: Warning Signs from Dresden’. He is sitting in a classroom of the Political Science department within the university. “It is the tip of an iceberg,” he responds, referring to the deeply complex, hidden and potentially dangerous movement that has grown out of a Facebook page formed in 2014. The Facebook page was purportedly a reaction to a pro-Kurdish workers party that sparked fears of Muslim immigration in Germany. Far right radicalism is not unique to Germany, with countries like Poland, France, England, Italy and Hungary battling against xenophobic and nationalist sentiment. Yet, it is Germany’s past that makes an organisation like Pegida a wound in the side of Germany’s need to show the world that history will not be repeated in their country.

Listen to part of Dr Patzelt’s talk here:

Today, Pegida still persists predominantly on Facebook (with around 250,000 likes), yet there are also weekly meetings in Dresden where thousands come together to light candles, hear speeches and to be ‘comforted by one another’ according to Dr Patzelt. In the past, these ceremonies saw over 15,000 demonstrators, but today it’s closer to 2,300 to 3,500. They speak about their fears of immigration, integration, economic competition and national identity. But Pergida is an organisation that Dr Patzelt believes the media has misunderstood by focusing too much on an extreme minority. It is a view which has made Dr Patzelt a controversial figure with many saying he is giving too much credit to what is largely seen as a dangerous neo-Nazi organisation.

Nonetheless, Dr Patzelt says civil society has pushed the radical voice of Pegida out of other German cities and is trying to do the same in Dresden. The letters ‘FCK PGDA’ on a street pole outside Dr Patzelt’s office capture the fact that many living in Dresden do not want to be affiliated to the organisation that has come to taint their country’s reputation.

Graffiti outside the Dresden Technical University.

‘Dresden – Place to be’ is an association of academic staff from Dresden Technical University that was founded at the same time as Pegida. They have organised numerous events that bring together refugees and locals living in Dresden through concerts, conferences, races, food festivals and social media campaigns among other events. They have been busy, with at least ten events in two years catering to tens of thousands of people at various points. “This is not only about people who think the same,” insists Annegret Shlutecke, one of the leaders during a talk explaining the organisation’s events. “It often brings people who want to know more; people who have yet to form their opinions or who are curious to meet others.”

Indeed, a plethora of civil society organisations and volunteers is trying to fill the gaps left by the state in Germany. Günther Schulze is one of these people who is now dedicating his retirement to ‘Wilkommensbündnis Steglitz-Zehlendorf’, a refugee welcoming committee. “We are an organisation of volunteers founded in 2014 that assists refugees in many ways,” he explains. “We assist with emergency housing, government advice on housing locations, donations, linking up volunteers with refugees and more. We receive no funding from the state, everything is volunteer-based. We are doing things the state should be doing, we are doing too much. We can do it now, but we can’t do this for the next 18 years.”

Refugees are given 600 euros a month for housing, yet finding spaces where refugees are welcomed is a difficult task. “Waiting is a part of the system,” he explains. “If refugees wait long enough they will be tempted to leave, and people know this.” Yet he remains optimistic. “I receive, on average, around 30-40 emails from people a day. They offer beds, chairs, a car ride, anything. I think I have received a total of 20,000 emails. Among these around seven were from AFD accusing refugees of being terrorists. But most people want to push against the fear of a neo-Nazi propaganda. As a child born just after the war, I think much of the way Germans have responded to the refugee crisis is linked to its history, and of not wanting it to be repeated.”

But is the state aware of the role civil society is playing in filling the vacuum left by what should be state responsibility? Member of Parliament, Frank Tempel, the Deputy Chairman of the Committee on Internal Affairs, speaks openly at the Buntestag about what the state has done right and wrong regarding immigration in the country. “A lot has been done by volunteers that the state cannot provide. Several tasks have not been adequately addressed by the state. There is little money to provide for them. The government needs to provide funds to municipalities to fund schools and teachers,” he says. As a former policeman, Frank has been exposed to numerous accounts of xenophobia and criminality, making him privy to the complexity and importance of working closely with communities on the ground. “I know that a lot of the subcultures in Germany are homemade.” Frank believes the state needs to invest in refugees both for financial and social rewards in the future.

Icht bien Berliner: Stories from Berlin’s Immigrants

The famous line ‘Icht bien Berliner’ was said by U.S President John F. Kennedy in 1963 when addressing West Germany. The line, meaning ‘I am a Berliner’, was meant to capture the United States’ support for West Germany after the Soviet-backed East Germany had erected the Berlin wall to prevent large numbers leaving for the West. It also captures the malleability of what it means to be a Berliner, or a German, and the changing face of national identities according to volatile political contexts.

For Monis Bukhari, a Syrian refugee and journalist who has been in Berlin for three years, Berlin is still not his home. “The biggest problem for me now is finding a job. It is almost impossible without any German language skills to find a job in Germany, besides my profession is journalism, and the journalist’s tool is the language. Then I found myself suddenly in an environment I know nothing about. I never planned to move to Germany, not even visiting as a tourist. I had to build my network from scratch.”

The value of a network or a community has been felt by both newly arriving refugees and immigrant communities from the 1960s.

The Turkish community centre amid the multicultural district of Wedding, in the centre of Berlin, captures a snapshot of the Turkish community in the city. ‘Refugees Wellcome [sic]’ is seen graffitied onto a nearby empty building wall. Security bars are visible on the windows of some buildings. “We built this park here to try to discourage drug dealers,” says Şükran Altunkaynak, the neighbourhood manager. “Sometimes we still find syringes but we believe the area has become safer.”

Levels of crime in the area speak to unemployment and marginalisation of the community members here. Nonetheless, the Turkish community centre is a site of refuge for many. A prayer call is played over speakers as people move through the courtyard to the mosque to pray during Ramadan. The centre has a small library and study room, and German and Turkish flags hang alongside one another from the windows of the surrounding buildings. “We always try to consult with the community to understand what they want,” says Şükran, pointing to the nearby benches built around the bases of trees. “Sometimes we can give them what they want, but not always.”

The Turkish community centre in Wedding displays Turkish flags

Community centres are also valued by Greek immigrants in Berlin. A traditional Greek barbeque has drawn friends together at the Greek Community Centre in Mittlestrasse in central Berlin. Kebabs, cheese, bread and meats are spread across numerous tables, with eyes flickering occasionally to the television, screening a Euro football game. Enthusiastic cheers punctuate animated chatter as people trickle in and out of the centre’s courtyard.

“There are about 300,000 Greeks in Germany,” estimates Thanos Liapas, a 28-year-old PhD student at Humbolt University. “And around 300 Greek restaurants in Berlin,” he laughs. Like many of his peers, he came to Germany following the financial crisis in search of greener, and more stable, pastures. “The centre has been here since 1990, and hosts dances, plays and political discussions. New migrants can consult with older ones to understand their employment opportunities and rights,” he says. If he had the opportunity, Thanos would return home. Eleana Athanasiadou, a 22-year-old Politics students, feels the same. They both agree that “Berlin is quite Mediterranean for a German city”, implying that they feel at home in the cosmopolitan melting pot the city has come to embody. “We do not experience explicit xenophobia here, but we know others have struggled with employment and housing issues,” she explains.

For newly arrived refugees and immigrants, community plays a valuable role in navigating a new city. There is importance in also acknowledging the success stories of refugees in Germany, while not forgetting the very real challenges surrounding immigration faced by the state and civil society today. Shan Rahimkhan, an Iranian refugee, arrived in Germany 20-years-ago. He now owns one of the most successful hair salons and restaurants in Berlin. “I am a Berliner,” says Shan, as he walks through his chic salon filled with Berlin’s most stylish and wealthy. “I became a hairdresser because I like women,” he laughs. “The government didn’t give me anything, I did it all on my own.” Shan, with his own restaurant, shampoo brand and cupcake store is fully aware that his lack of xenophobic encounters has much to do with his celebrity profile. ‘’Berlin is a microcosm,” he admits, yet he is proof that within this microcosm, integration and success can be synonymous with immigration.

Immigration of the future

At the Dresden train station an old German lady walks slowly between the crowds, carrying a pot of lilies and smiling into the crowd. She happens to find an open seat among a group of journalists moving through the country to better understand immigration and integration in Germany.

She introduces herself in broken English and begins with some small talk before moving onto her own story and about her life in Germany. “I had to flee during the War,” she explains. “I hid in my mother’s suitcase.” Soon she pulls out a carefully folded sheet of paper containing a prayer and her religious story and how she found Jesus. She distributes the paper before asking why these journalists are in this train station. Her expression changes, the smile quickly fades. “The problem with these refugees is that they come here to spread Islam,” she laments. “They come with hope, but they also come to take over with their religion.” One can see the anxious sermons of her priest pulsing through her tense gaze. The irony of her personal history alongside her xenophobic views seems to be lost on her.

Germany, and its present treatment of refugees is inextricably tied to its past. “Today we are having fringe groups blamed for the country’s problems, as in Nazi Germany,” says Frank Tempel again. “This happens because there are seemingly no other scapegoats for failed social policy. If we fail to explain why there are homes for refugees but not for Germans then this can breed resentment.” Both political and environmental refugees are unlikely to stop moving across borders in the near future, and although Germany is seen as doing more than many European countries, voices on the ground emphasise the deeply divisive narratives surrounding refugees and migration in the country.

Individual success stories like Shan’s, the strength of immigrant community centres and the activism of civil society organisations within the country stand in contrast to the doomsday predictions of groups such as Pegida. While immigration is not a panacea to Germany’s demographic or social problems, a nuanced understanding of both the experiences of refugees arriving in the country, and the anxieties of those who fear their arrival are vital to ensuring that integration is a sustainable option. “We lost the first generation of Turkish immigrants into Germany,” reflects Fredericke at the end of the visit to the school. “We will lose this generation of refugees if we do not educate and integrate them soon enough.”

It seems that Oscar Wilde was wrong: for those who have already fled conflicts across multiple borders, learning German could not happen fast enough. Yet education needs to occur in two ways: both for refugees and for German society. This will ensure that ‘integration’ is not another empty catchphrase that, if poorly executed, may only breed further division.

All photos by Kim Harrisberg.