Britain’s asylum system is failing women. The government promises in its foreign and international development policy to promote and enforce the rights of women caught up in the horrors of conflict and poverty. Yet when those same women arrive on these shores, domestic policy fails to give them a fair hearing. Asylum Aid’s Zoe Gardner explains why and introduces the campaign promoted by her organisation.

We are failing women survivors of rape and violence, simply because they have come to this country seeking protection.

There is a glaring hypocrisy in the way we treat women survivors of rape and violence in Britain. We make advances to protect survivors of abuse at home and around the world, but then allow women seeking asylum to fall through a protection gap and deny them the same standards of care as other women. At Asylum Aid we’ve started a new campaign to persuade the Home Secretary to close this protection gap by applying equal standards of protection from violence to asylum-seeking women and girls too.

An odd couple came together over last summer; the global superstar Angelina Jolie joined forces with our own, slightly awkward, then Foreign Secretary, William Hague, to stand up against one of the most appalling global epidemics of violence: rape as a weapon of war.

The Global Summit to End Sexual Violence in Conflict was an opportunity to hear the voices of the survivors, mainly women, of brutal abuses around the world, it was a time to reflect on the many injustices we have yet to overcome, and a proud moment for the British public, to see our government standing up on an international stage to loudly condemn violence and brutality towards women and girls.

The major output of the Summit was an International Protocol, signed by representatives of the over 100 countries in attendance. The Protocol stipulates international standards for the investigation of rape in conflict situations, and lays down basic standards of care for the survivors.

The Protocol outlines recommendations on how to secure prosecutions for rape in war and includes guidance on basic standards to follow when women survivors come forward asking for protection:

- No woman must be forced to tell her story of abuse in front of her children.

- Women must be able to choose to speak only to a female interviewer and interpreter if they prefer not to talk about their experience to a man.

- Interviewers and interpreters must receive training on the effects of trauma on memory, so that no woman faces being misunderstood or disbelieved because she has been traumatised.

- Women who report rape and violence must be referred to counselling to enable to them to begin to recover from their ordeal.

- Women must be given clear information to allow them to understand the process and understand their rights as women within it.

To many of us I’m sure, these sound like fundamental provisions, necessary to allow women to come forward and be fairly heard. In fact, they resemble the basic standards that we in the UK take for granted when a British woman reports rape or domestic violence to the police.

It is a shocking and uncomfortable reality, therefore, that when women and girls come to this country seeking asylum, in some cases fleeing the very same conflicts targeted by summit, we do not offer them these basic measures. Indeed, research has shown that well over half of the women who seek asylum in the UK have experienced rape, yet apparently, as soon as one of these women crosses a border, according to our government, she is no longer entitled to the same rights as any other survivor of rape.

The Protection Gap Campaign

The five rights outlined above form the basis of Asylum Aid’s campaign to close the Protection Gap launched this winter as part of the Women’s Asylum Charter. The Charter brings together 355 organisations in support of the rights of women asylum seekers.

We think it is unacceptable to discriminate against the brave women who escape persecution and search for a better life in this country. We believe that if our government says women need these rights, then they should apply to all women, regardless of their immigration status.

We want our MPs to urge the Home Secretary to put in place the very same compassionate measures that her colleagues in the foreign office are standing up to defend on the global stage. It is hypocritical for politicians to loudly condemn violence against women in other countries, and then fail to speak up for asylum seeking women in Britain too.

Asylum Aid’s protection gap campaign

This hypocrisy is recurrent. It was seen again last year when Theresa May introduced new measures to protect girls in our communities from Female Genital Mutilation. While a commendable effort is being made to protect young British girls from this torture, women from abroad making claims for protection on the basis of FGM are regularly denied sanctuary. As Nafeesa*, an anti-FGM activist from Yemen, an asylum seeker, and supporter of our campaign says:

“I cannot prove that I am at risk with a piece of paper to show it. But even in this country, where FGM is illegal, and there is a strong police force, we know that FGM is happening. Even though they go on the TV and they talk about stopping it, still it is happening here. How can they say that I can go back, where the law is in the hands of the strongest?”

Why female asylum seekers are at a disadvantage

There are many reasons why women in particular are at a disadvantage within Britain’s asylum system. Historically, this has been the case. The 1951 Geneva Convention, often referred to as the Refugee Convention, is the treaty on which all our asylum legislation is based.

It was designed in the aftermath of the Second World War, and reflects the concerns of the time. The Convention defines a refugee as someone who has a well-founded fear of persecution in their country of origin, on the basis of one of the following five grounds: Race; Religion; Nationality; Political belief; or Membership of a Particular Social Group.

As our legal norms have developed in the UK, it has generally been recognised that persecution may also be likely to occur on the basis of other grounds, including sexual orientation, for example, or indeed, gender. But our legal system does not allow a person to be recognised as a refugee because of persecution on those grounds, rather those types of abuses have to be made to ‘fit’ one of the above categories, meaning that they often are more complicated cases to argue and defend.

If a woman is married to an abusive husband in Pakistan, for example, societal traditions will dictate that she may not be able to leave him or seek a divorce without facing the risk of severe retribution. She has no law to protect her, as domestic violence is not criminalised in Pakistan, nor can she expect any assistance from the police or local authorities. Often, she cannot even rely on her family members to protect her, because of the perceived “shame” she will bring them. In this instance, it could be argued, that she is facing persecution simply because she is a woman. But the refugee convention does not allow us to offer her protection on those grounds.

Instead, a lawyer will have to argue that women survivors of domestic abuse in Pakistan are treated as a ‘particular social group’, and that those are the grounds on which she is persecuted.

It is similar in the case of women or young girls who are at risk of female genital mutilation (FGM), or of forced, early or child marriage. In none of these cases is it easy for a woman to be recognised as a refugee within our system, despite a clear risk to their safety in their country of origin.

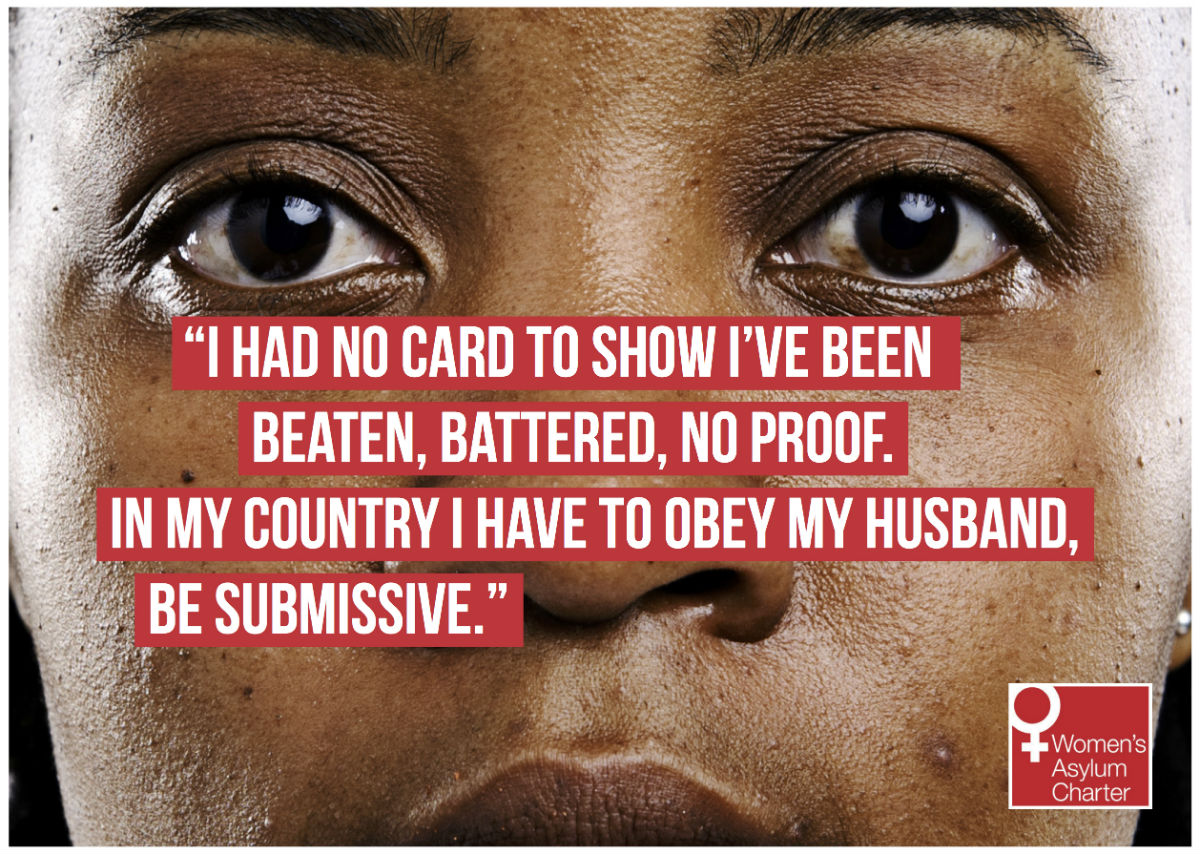

The next obstacle in the path of women refugees in particular, is how to prove that they need protection. There are some dangers that both men and women might face where it is possible to prove at least a part of the story using documentary evidence; if they are persecuted for their political activity, for example, they might have a membership card for an opposition party, photos of themselves at a demonstration; identity documents may allow one to prove nationality or ethnic background; and membership of a religious minority may be demonstrable through evidence of attendance at communal worship.

Asylum Aid image. The charity campaigns for a fair and more efficient asylum system in the UK.

What characterises the persecution that is specific in most cases to relating to women, however, is that it often takes place in the private sphere. Women are not given a certificate proving that they have experienced domestic abuse, or rape. It is much harder for them to produce any documentary evidence for these types of persecution.

For this key reason, women are far more likely than men to be forced to rely entirely on their own oral testimony, their ability to explain their story accurately in order to demonstrate why they need to be protected. And this is why it is important that the process for women asylum seekers is reformed to allow them a fair chance to make their claims.

Why our plans will make a difference

Survivors of horrific violence need the same compassion that we would show to survivors here.

The following five provisions go a long way towards making the asylum system fairer for women:

- Training for interviewers and interpreters on the effects of trauma on memory. Research has shown that people suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder may have difficulty recalling traumatic experiences in detail, or be unable to recount what happened in precise chronological order. Any inconsistency in the story given by a woman seeking asylum, however, may be counted against her “credibility”, and contribute to a refusal to allow her to stay. Interviewers and interpreters need to receive adequate training on this issue if they are to make fair decisions on women’s cases.

- Female interviewers and interpreters. Often women will find it difficult to discuss issues of rape, domestic violence or FGM in front of a man, and so will not disclose this if forced to speak to a male interviewer or interpreter. Some of the women may have come from a cultural background where discussing such things with men would be shameful or taboo. If at a later stage she does disclose this information, when speaking to a woman, a doctor, or a counsellor, or when more trust has been built up over time, this late disclosure can count against her “credibility”. Having female interviewers in place could prevent this happening.

- Childcare during the asylum process. Women may also withhold traumatic information if they are forced to bring their children with them into the interview because there is no childcare available. When asylum seekers come to this country they are dispersed to different regions while their claim is considered. Some asylum offices provide childcare during interviews. Some don’t.

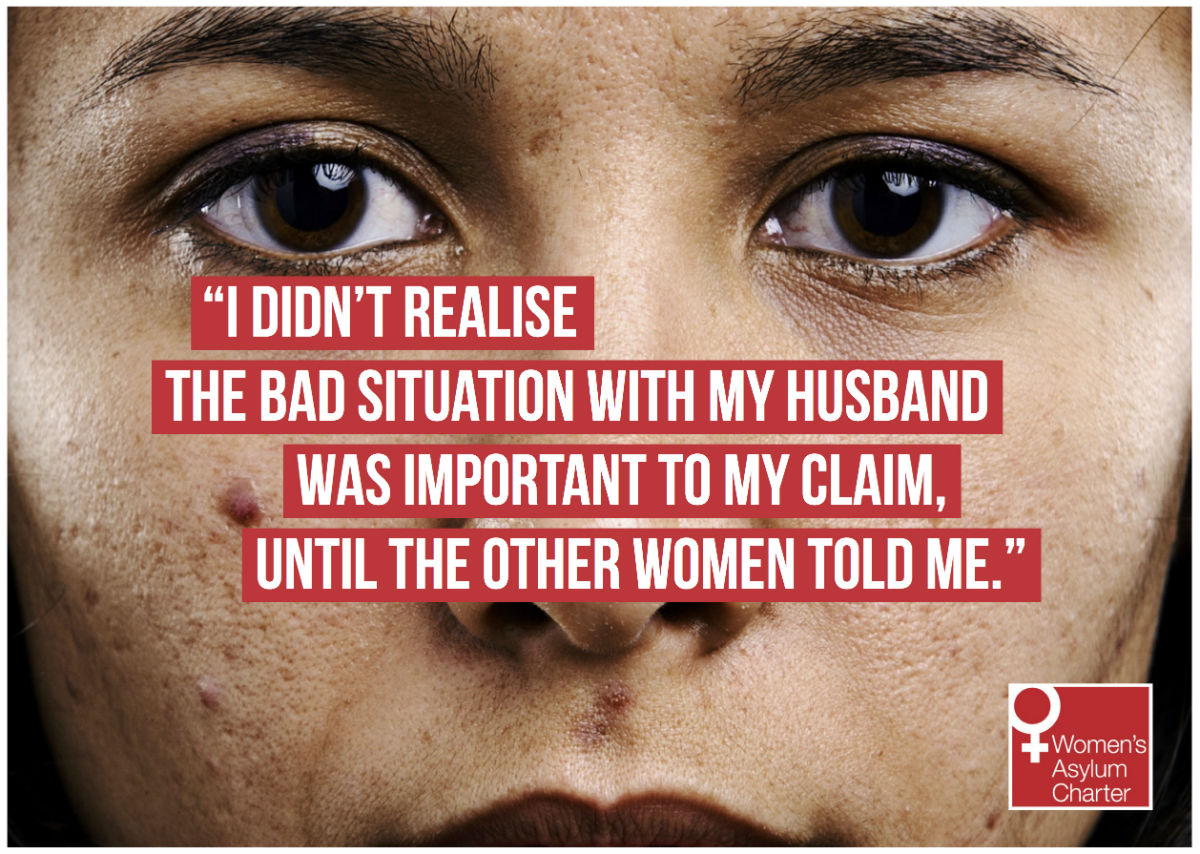

- Information. A woman might simply not know that her rights are protected in this country, and that the abuse she has suffered would be considered a reason to allow her to stay. Therefore she may not disclose her most traumatic experiences, not thinking that they are relevant. Again, if she later brings up something of this kind, she may be disbelieved, simply for not raising it earlier. It is only fair to give women clear and specific information about their rights within the asylum system, so that they know from the start what is expected of them.

- Counselling. Finally, it may be difficult for women to talk about what they have gone through at all without being given the chance to talk to a counsellor and receiving psychological support.

Jendyose’s story

Jendyose*, arrived in the UK from Uganda at the age of just 16. Her mother had died, her father had been abducted and detained for his political involvement, and Jendyose had gone into hiding at the house of a family friend.

Her hideout soon became her hell, however, when she was raped by two men brought to the house by the friend. With nowhere left to turn, she entrusted her life to smugglers and fled the country. She was abandoned by the smugglers in London, with no idea where she was.

A sixteen-year-old orphan, survivor of brutal sexual assault, Jenyose was unable to come to terms with what had happened to her, or to tell the story in her asylum interview. She became depressed, and when her application for protection was rejected, she attempted suicide. It is obvious that a vulnerable girl such as this would benefit from counselling and needed to be dealt with by professionals trained on trauma. It is clear, too, that had she been treated with more compassion from the outset, she may have been able to explain her situation better and avoided the additional trauma of the appeals process. Once she was able to communicate her whole story, she was finally granted the protection she deserved and given the right to start her life again in the UK.

Saving lives

Asylum seekers are portrayed as a strain on this country’s economy in the populist press, while the question of how much money is wasted on correcting our dysfunctional asylum system is ignored. Just over one in four of all asylum refusals are later overturned by the courts on appeal.

Home Office staff get it wrong and send someone back to danger in one in every four times. This is a staggeringly high rate, and our research at Asylum Aid has shown that when separated out by gender, the rate can be even higher, meaning women are disproportionately likely to be threatened with being sent back to persecution.

If decision-making was consistently poor in any other area of governance involving important decisions about vulnerable people’s futures there would surely be an outcry. So why do we allow asylum seeking women to be mistreated, at such great cost, both to our finances and to innocent lives?

In Jendyose’s case, the appeals process and the courts acted as a safety net, to overturn the Home Office’s initial decision and prevent her from being removed to face a real and terrible danger. How many other women and girls have slipped through this protection gap, unsupported? How many women and girls have been sent, by our government, back into the hands of their abusers, just because they were too scared or damaged to navigate the asylum system?

We are asking people to stand with us and write to their MP to support the rights of asylum seeking women. Every card written by each one of our supporters throughout this campaign will be printed out and delivered to MPs in parliament. We do not want MPs to brush this issue aside, we want every politician in the country to hold in their hands an image and a quote of a woman who has been affected by the injustice of our asylum system.

The demands of the campaign are not unreasonable or difficult to achieve, and if we are able to show the numbers of people who support it, we can put enough pressure on the Home Secretary to achieve the changes that could save the lives of women like Nafeesa and Jendyose and more besides.

*Names have been changed to protect identities