I’m drinking a good rum donated to me by a benevolent friend, he’s drinking a cheap vodka bought from the corner shop. And we sit, and we stay up all night, and we talk.

Morris (a pseudonym that began as a joke about Morrissey) is a well-read, articulate middle aged man who has a way with words. His ability to stretch and weave the English language as he attempts to show me some of his thoughts and feelings astounds me. And yet he doesn’t recognise it. He doesn’t brandish language to impress; language is a tool for him. It is a way to make sense of and explain the world as he sees it. Without it, I would have no window onto the hidden complexities of his ideas. But it’s more than that, too; it’s a way of creating and shaping meaning.

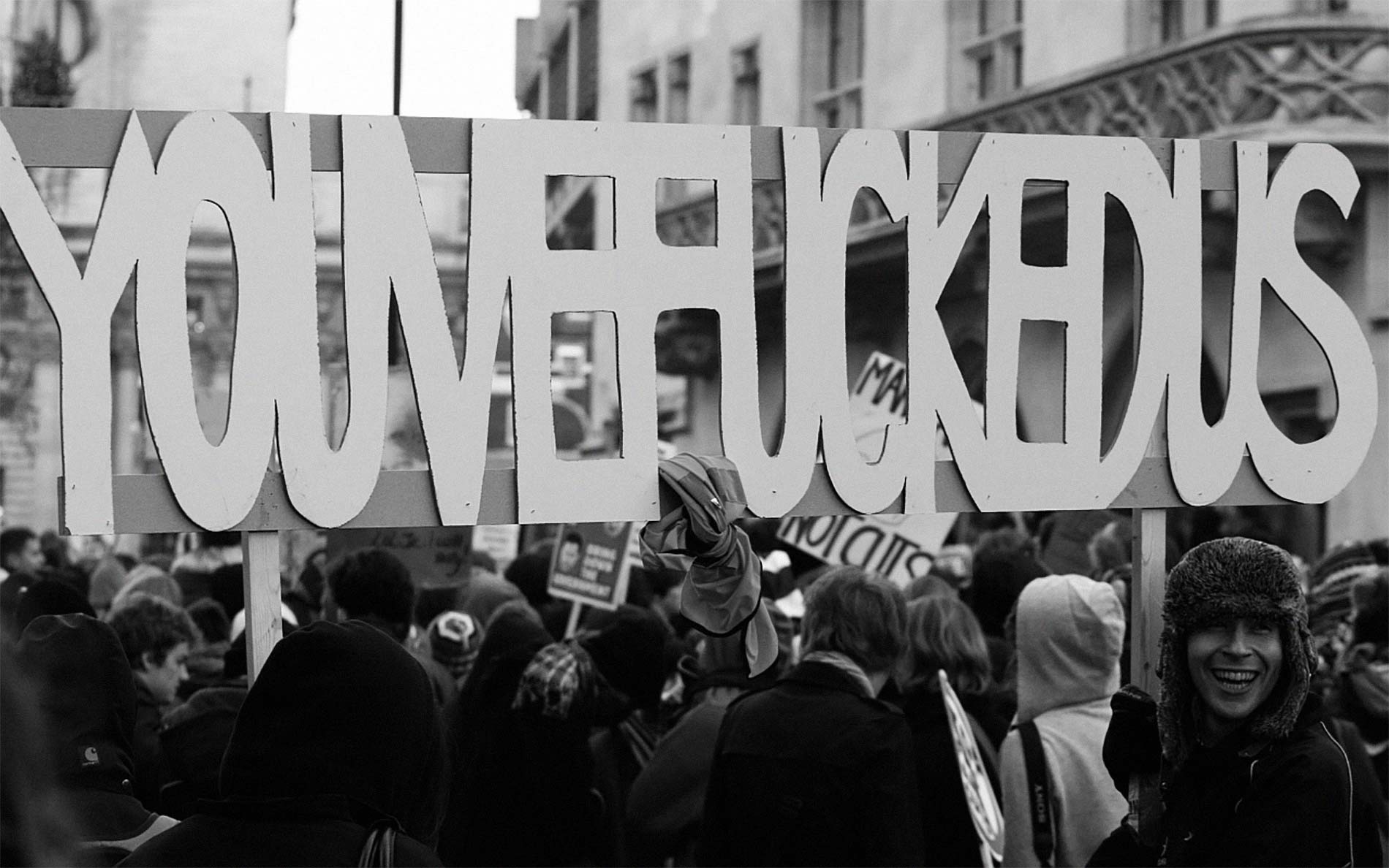

Morris is one of my ‘research participants’. He is a key player of UK Uncut, the grassroots movement that I’m researching. UK Uncut protests against the government’s austerity programme and seeks to present an alternative to the dominant narratives that are broadcast by those in power. It argues that ‘the public spending cuts are based on ideology, not necessity’ and strives to challenge such ideologies, arguing instead for fairer options to the cuts, such as targeting tax avoidance in large corporations. Crucially, UK Uncut aims to raise awareness of the ways that narratives are deliberately constructed within politics and to challenge them. It’s about questioning that which we take for granted, not merely accepting what is presented to us by those in authority.

UK Uncut encapsulates an important side to protest: that of creating and subverting meaning. It is a process that is intricately woven and undone. James Jasper wrote in his book, The Art of Moral Protest, that as humans we add layer upon layer, creating thoughts about previous thoughts, attaching new moral values to existing ones, working out how to feel about our own feelings. We are aware of our awareness about our meanings and so on, with infinite complexity’. Protest is personal. It’s about relationships, emotions, and beliefs. The issues that matter tend to be those that are perceived to have a personal impact upon individuals and it’s that personal attack (whether it be on yourself, your family, your friends, or the values you hold close) that incites action.

Many activists tell me that it is outrage and moral indignation which motivate and sustain protest. It’s these fiery emotions that compel activists to stand for hours outside in the cold, protesting against injustice and seeking to forge new understandings. Indeed, Morris says that ‘believe it or not, I’m quite reserved myself. It’s anger and indignation that makes me push myself forward, not self-confidence’. It’s often emotion, then, that is the driving force that propels activists. For me, it underlines the most important point of protest: its representation of humanity.

Protest is a distinctly human activity. It’s about fighting injustice and standing up for what you believe is right.

Protest is a distinctly human activity. It’s about fighting injustice and standing up for what you believe is right. It’s about having compassion, perceiving a common humanity and being prepared to fight for the rights and dignity of others. Here, the personal extends to the collective. Nelson Mandela said ‘our human compassion binds us the one to the other – not in pity or patronizingly, but as human beings who have learnt how to turn our common suffering into hope for the future’. It’s this underlying human spirit and bond combined with the ability to look forwards with hope for an alternative that makes protest an essentially human activity. It’s also this that allows us to shape meaning together, as a communal activity. Morris says to me, ‘When I can finally close my mind to my own problems, there’s still a billion screaming voices of the small folks shafted by the system keeping me awake. When we finally have justice and the voices become quiet, then I can finally sleep’.

And so, on a sleepless night, Morris and I sit up. Drinks in hand we tell each other story after story, slipping in and out of personal troubles, the mundane and the grand. One minute discussing trivial woes, the next raging at wider, worldly, injustices. Many researchers would question how appropriate it is to form bonds with your research participants. They might argue that instead, there should be structured, recorded, and formal, interviews with participants or ‘subjects’. There should be a distance and a separation between the researcher and the researched. This way the researcher can retain an objective viewpoint from which to survey the data they collect. There most definitely should not be late night, open and free-flowing conversations where meaning is created and shared over a drink or two.

But reality is more complex than ‘shoulds’ and ‘oughts’. It’s a tangled, often messy scenario, particularly when your ‘subject’ of study is human beings. At the end of the day (or evening), we are both humans with emotions and beliefs, trying to make sense of the world around us. Truly, as Jasper says, ‘Who are we humans, who protest so much? Most prominently, perhaps, we are symbol-making creatures, who spin webs of meaning around ourselves.’

Morris and I sit, and we sip our drinks, and we talk, surrounded by the strands of our webs.

Photo by bobaliciouslondon ![]()

![]()

![]()