Many of the government’s spending cuts will have a disproportionate impact on Black, Asian, and other ethnic minority women, according to a recent report produced by the Centre for Human Rights in Practice, Coventry Women’s Voices and Coventry Ethnic Minority Action Partnership.

Layers of Inequality Report

The Layers of Inequality report published last year found that, taken together, the combined impact of job losses in the public sector and cuts to spending on welfare benefits, education, health, legal aid and voluntary services, will exacerbate existing inequalities that black and other ethnic minority women face.

Kalwinder Sandhu is one of the report’s authors. A software engineer by profession, she knew the research would uncover some unpleasant findings, but was still shocked by what she found, as well as frustrated by the lack of information held by public sector bodies on the impact of their policies on different groups. In the following article she describes the difficulties of putting together a report that assessed the impact of a diverse range of public spending cuts on black, Asian, and minority ethnic (BAME) women. And how it made her feel differently about her own race and gender as a result.

Finding out the Facts

I was several months into my research on the impact of the government’s spending cuts on BAME women when I first began to despair. Unexpectedly, the more I researched, the more it affected me emotionally. What triggered these feelings was coming to understand just how many individual cuts would impact BAME women.

It’s well documented that women are likely to be hit harder than men by the spending cuts. They form the majority of the public sector workforce, so are more likely to lose jobs; they use public services more than men, so will feel the pinch as the government rolls back state provision; and they rely more on benefits, an area under constant attack. But different groups of women will fare even worse; when gender is combined with ethnicity, class, disability or age the negative impact of austerity is compounded. That is when it really begins to look terrifying.

BAME women already face multiple disadvantages in our society. They’re more likely to live in poverty, rely on working age benefits and tax credits for a high proportion of their income, and they’re disproportionately represented in low paid employment. They also face historic and on-going disadvantage, discrimination and racism within society. Now, consider such factors alongside the government’s austerity measures. The cuts to welfare impact on the poorest in society hardest, and BAME women are disproportionately affected because they are more likely to be poor.

But some welfare benefit cuts also impact on some BAME women disproportionately because of particular circumstances of their lives. During my research I stumbled across one reform to housing benefit called ‘non-dependent deductions’ which was not covered in any of the mainstream media on the public spending cuts. ‘Non-dependent deductions’ were introduced because there’s an assumption that anyone over 18 (an adult son or daughter perhaps) and living in the same house will make a contribution to paying rent. By the government’s own admission, black and minority ethnic families are more likely to live in extended families. So it’s no surprise that these families are more likely to be affected by the deductions.

It was interviews with housing specialists in Coventry that made me realize just what an issue this was likely to be. Ed Hodson from the Citizens Advice Bureau told me:

Non-dependents deductions went largely ignored as a public issue but for any tenant with extended family living in their house/flat this was a significant blow to their housing benefit causing, potentially, family stress and breakdown where contributions were demanded when attempts were made to absorb these reductions in housing benefit. This was, arguably, just as big a blow to housing benefit recipients as the bedroom tax is now.”

Non-dependent deductions weren’t the only problem I found. In September 2011, the government first announced plans to penalize jobseekers who refuse to learn English. There was little political fuss about the requirement. But one BAME women’s voluntary organisation told me:

We had 60 women who wanted to enroll for ESOL, but only 10 of them met the criteria for funding. Henley College, which provides ESOL courses through our centre, have had a reduction in childcare support, which means that we cannot offer childcare places to all the women who want them.

These women want to learn English, but for many of them the changes to the criteria in accessing classes, cuts to ESOL provision, and a lack of childcare make that impossible. And these same women were finding it harder to access health and other public services because translation provision has been cut. In some of the cases I looked at, adult children and school-age girls had to take time off work and school to assist elderly parents with translation.

Individual cuts are bad enough. But it’s the combination of cuts that is most devastating. I researched cuts and changes in employment, housing, welfare benefits, education and training, health, social care, legal advice services, cuts to voluntary services and cuts that affect women who are the victims of violence. When taken together, some women and families are really going to suffer. A black or ethnic minority mother with five children will lose a huge chunk of support including frozen child benefit, the benefit cap, the maximum four bedroom housing allowance, and non-dependents deductions. If one of her children is in post-16 full-time education they’ll also have lost the Education Maintenance Allowance.

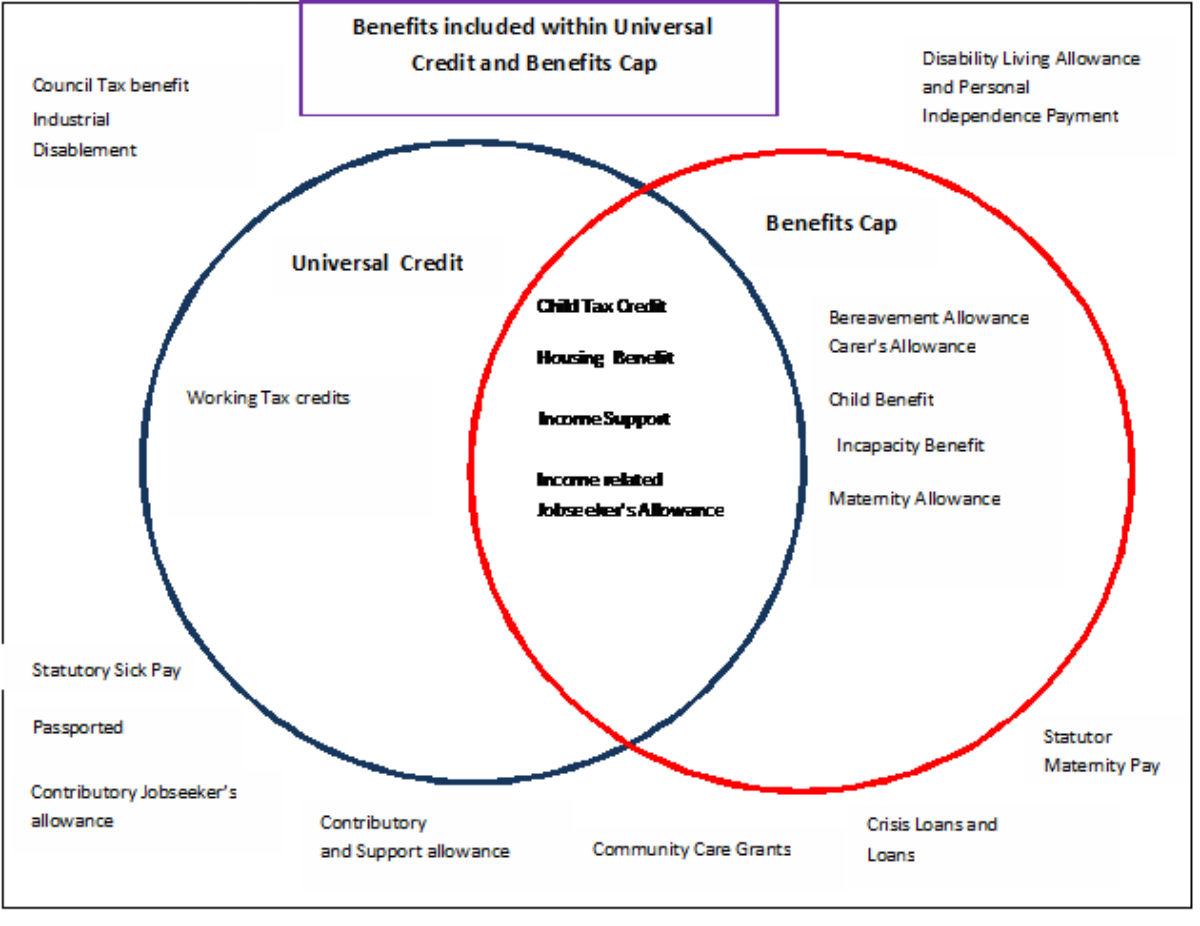

It took me a while to process all the changes and understand how they related to one another. There are just so many that it’s difficult to know how they all intersect. I’m a software engineer by profession and used to using logical analysis to assess a problem. So, I put together a Venn diagram to show which benefits are included in the Benefit cap, which are in Universal credit and how they intersect.

Venn diagram

It was only after putting together the diagram that I began to realize the complex web that people were facing. I’m not sure many of the women I interviewed for the report would be able to fully comprehend the extent to which their lives would be affected. The choices they must make are stark; do you buy food? Or do you pay the rent shortfall? What if you experience poor mental health? Or lack the confidence to communicate in English? How do you work out and prepare or plan for these changes?

Sons, not daughters

I put some of these questions to women in focus groups; the response was alarming. One woman said:

My husband has lost his job and we don’t have much money. So we are only thinking about now sending our son to university and not our daughter

It was worrying to see other women in the focus group nodding in agreement. From my own experience I know that sending a young woman to university is a family decision in some situations. My uncle in India, another uncle in Canada, as well as a host of uncles in England, all had a say in the future of my education. Their views varied. One thought it was not worth sending me to university because “it was another three years of not earning a salary”. Another: “Going away to university may lead [me] to temptation and could result in the loss of the family’s honour.”

Many young women from black, Asian, or ethnic minority households impacted by the cuts (combined with the hike in university tuition fees) will be the first to go without. And if that happens, imagine a future where young women lose the opportunity to fulfill their potential. Imagine the impact on their children?

Who counts BAME women?

Another thing that struck me was the lack of local and national data disaggregated by gender, race, and disability. Often the data was broken down into gender or ethnicity, but never both. And where race was counted, it was split simply into white and BAME, obscuring the significant differences between ethnic groups.

Access to data that did exist was also difficult. Sometimes I was asked to pay for data, and other times I was sent from agency to agency, made to fill out form after form, before getting anywhere. The lack of accessibility of data made it difficult to monitor the impact of austerity policies on BAME women. I was determined and put considerable effort into finding the information I needed for the Coventry project. But how do we measure national impacts? Without data broken down into both gender and race, it’s impossible to accurately assess and monitor the impact of austerity policies.

Some of the figures I did manage to uncover revealed stark differences in employment levels for BAME women compared to white women. Unemployment among black and minority ethnic women in Coventry increased by nearly 75% between 2009 and 2013, compared to 30.5% for white women (also high). Breaking down these figures further, unemployment had increased by a staggering 272% for white non-British or Irish women (mainly Eastern European migrants), 160% for mixed ethnicity women, and 87% for black British and African Caribbean women. These figures show the importance of exploring the different experiences of different minority ethnic groups of women and the particular barriers they face in getting back into work.

I also found a hidden reality behind data collected. I heard plenty of evidence from Unions that black, Asian and minority ethnic women were affected across the country by public sector job losses. Yet data collected by Coventry City Council on early retirement and voluntary redundancy showed no significant impact on BAME women. This discrepancy seemed odd. But then it was pointed out to me that those taking voluntary redundancy are more likely to be white and at the end of their career, while those facing compulsory redundancy are likely to be more junior and from a black or ethnic minority background.

In both cases a job has been lost, but the impact of a voluntary redundancy with a reasonable payoff given to someone close to retirement age is far different from a compulsory redundancy with little pay off, early on in one’s working life.

The demonization of ethnic women

As the government made its case for the cuts, and I became immersed in my research, I began to notice a parallel demonization of black, Asian, and minority ethnic women. I felt strongly about including this observation within the final report. The experience of the cuts must be seen in the context of the lived experiences of BAME women, including historic and continued disadvantage, discrimination and racism.

I was initially nervous explaining my thinking to my two white colleagues from Warwick University, unsure of how they would react to such a statement. But, much to my relief, they agreed. Why on earth had I thought otherwise? It made me realize how much I still worry about the level of awareness and acceptance of my views on race and whether my experience will be seen as credible.

This is a recurrent issue for BAME women navigating work and life, balancing the need to speak the truth of our lived experience, and the desire not to be judged as the stereotypical ‘angry black woman’. The cuts come on top of these daily challenges we face because of our gender and our ethnicity, which are made worse by other factors such as poverty or disability.

What has struck me in conversations with other BAME women is that in many ways we have always faced ‘sanctions’ in one form or another, we just never had a name for it. A colleague recently mentioned that job seekers are now being sanctioned for transcription errors when filling out forms, such as completing the name in the date column. This reminds me of when I completed my mother’s British nationality papers five years ago.

An immigration lawyer told me that if I completed the form incorrectly the UK Border Agency could decide to keep my mother’s £900 fee. This put added pressure on me to ensure I completed it accurately: my mother is on a state pension and £900 is a lot of money for her to lose. The sanctioning for minor mistakes has become mainstream. Minority ethnic people have experienced this type of condition for a long time.

Whenever my mother went to collect her ‘family allowance’ and was shortchanged, she felt there was no recourse because of the language barrier and because she wouldn’t be believed. To me, this is officially-sanctioned discrimination. One could argue that being shortchanged when receiving benefits is a thing of the past, but this systematic discrimination means that it’s now disguised in a different way – not so overt but covert.

When the personal becomes political

Black, Asian and ethnic minority women face many barriers and disadvantages in society. These spending cuts exacerbate those inequalities. Non-dependent deductions are just one example of the kind of cuts to benefits that are likely to have a really devastating effect on some BAME families. But there has not been any big political fuss about this issue.

Researching the report, I wondered whether the reason was that people were just less concerned about a measure that primarily affected BAME families? The societal impact of all the cuts combined could be huge: BAME women may never have the opportunity to realise their potential. If nothing changes, that is a burden we will all have to carry in the future.

My colleague Mary-Ann Stephenson always says all of us are just one job away, one divorce away, one long-term illness away, from needing benefits. For BAME women, we are one forced marriage away, one family decision away, from the loss of a life lived to our full potential.

I have always been interested in the issues that affect BAME women because as ‘the personal is the political’ my experiences stem from being Asian and a woman. In fact, I always felt my race was the higher priority to fight for – I am seen as an Asian first, and then as a woman. Although I always saw intersectionality as part of my thinking linking my class, race and gender, I accepted the traditional route of binary thinking about women and race. Only since I had been involved with this report on the cuts did I re-think the binary nature of the discourse around race and gender. It brought to the fore my ability to articulate all the inequalities that affect me, and not one at the expense of the other.