The Afar nomadic indigenous people of East Africa are fighting to preserve their distinct way of life amid climate catastrophe. In this striking photo essay, Afar women, children and elders explain how the climate crisis, infrastructure megaprojects, and conflict are affecting life for nomadic communities in Ethiopia.

Aboubakr, 55-year-old Afar chief, stands contemplative against the backdrop of his native Lalibela.

At 2,600 meters above sea level and east of the Simien Mountains, the elevation forms part of the East African Rift System, where the Earth’s internal forces are currently tearing apart three continental plates, creating new land.

“Land is constantly changing, transforming – sometimes quietly”, meditates Aboubakr, adding, “other times it decimates everything on its way.” He is alluding to the prolonged drought that has plagued the country for three decades.

Pictured: Aboubakr

Ethiopia is heading into its sixth consecutive failed rainy season, leaving 20 million people across the southern regions of Afar, Oromia and Benishangul-Gumuz grappling with a higher incidence of food insecurity, rampant poverty in climate-sensitive sectors such as agriculture, and dire sanitation and hygiene including cholera outbreaks precipitated by recurring flooding.

More than half the population is in acute need of humanitarian assistance, with over 20% of the population facing extreme food shortages, severe malnutrition exceeding 30%, and unprecedented death rates by starvation.

“As of 2023, at least one person succumbs to hunger every 48 seconds as ‘the worst famine in the 21st century’ threatens a total collapse of livelihoods in drought-stricken East Africa”

Abera, a 65-year-old coffee farmer and father of 11, used to run a successful business that provided income to take care of his family. “Now, I can’t even afford to feed them,” he says.

Scarce seasonal rain, reduced crops and the resulting all-time high 37.7% inflation in May 2022 are driving food prices up and eroding access to food. High rates of livestock deaths due to “apocalyptic temperatures” (says Abera) are further putting pressure on the 1.8 million Afar in East Ethiopia predominantly reliant on cattle rearing.

“The hunger crisis is particularly dangerous for children whose bodies have been weakened by insufficient food” says Aboubakr. By March 2023, Ethiopia’s infant mortality had peaked from 39 deaths per 1,000 live births to as high as 125 per 1,000 live births amongst Afar demographics.

“Nature takes what She wants”, he softly adds.

North east of Lalibela by around 280 km are the acid pools of Dallol. In a surreal landscape of colours, dominated by luminescent ponds of yellows and greens, boiling hot water bubbles up like a cauldron, whilst poisonous chlorine and sulfuric gas choke the air. The dry, violent landscape means that few plants or animals can survive here.

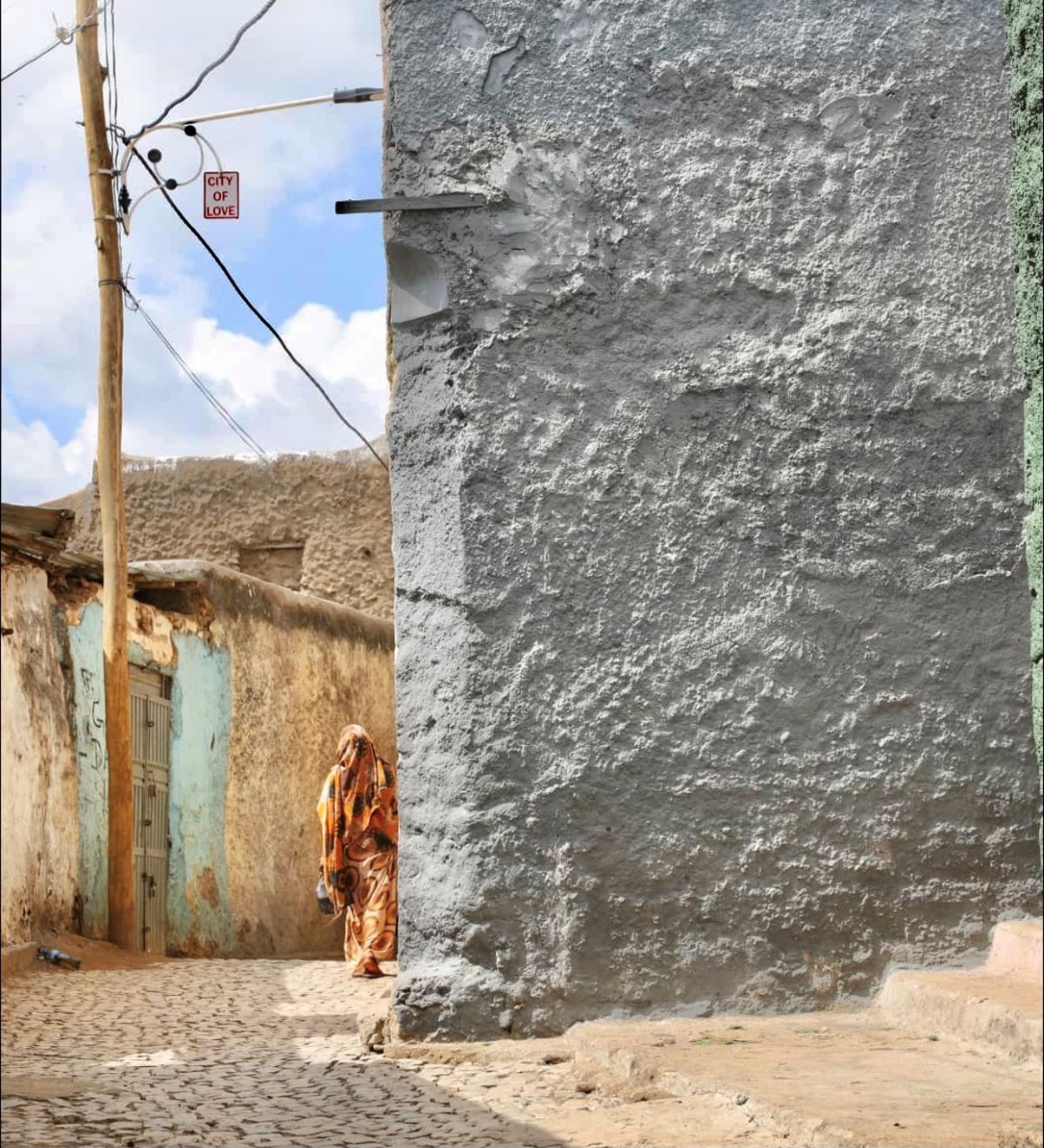

The Dallol site itself is unpopulated, with most Afar nomads having settled in the nearby semi-permanent village of Hamed Ela. Once the hinterland of free-spirited roamers and whirling dervishes, the Danakil Desert’s bestial landscape is prompting a mass population exodus, with informal urban dwellings and improvised slums popping up on the territory’s outskirts near Me’Kele, the provincial capital of Tigray, further west.

For the subsisting Afar, who make up 1.73% of the people in the region, the sacrificial transition to a sedentary lifestyle in Hamed Ela “will hopefully preserve our existence,” says Tamrat, a 21-year old volunteer who runs youth sessions on indigenous restorative justice. Another herder says the settlement embodies “the last outpost of [Afar] civilisation” and the “physical manifestation of our passage on Earth”. But, he adds, the “continuation of our traditional rituals remains under threat”.

For centuries, courtesy of the rain, pastoralist farmers set up camp in the flourishing pastures down the coast in the winter. In the summer, when the sun shrivels the vegetation, Tamrat says animals “would naturally move towards the high mountains… to signal it’s time to travel up into the amba”, the high Riftean plateaus known for their abundance of grass and fodder. Seasonal migration continues into the autumn when the rain regenerates the meadows on the coast and tribes can come down again.

By virtue of a nomadic lifestyle that’s intertwined with nature and at the mercy of its whims, climate change is now altering the course and pace of their annual journey.

No longer are the days wandering the length and breadth of Great Rift Valley, herding livestock from lowlands and highlands bordering the littoral in search of fresh grazing land and water sources. “We face challenges finding enough water or food to sustain us,” says Tamrat solemnly. “There is not enough rainfall.”

With hunter-gathering no longer viable, the loss of pastoralist mobility is forcing the Afar to surrender indispensable nomadic practices traditionally used for biodiversity conservation. Local communities like the Afar, which have coexisted with complex ecosystems for centuries, are the guardians of invaluable knowledge and experience of the rehabilitation of degraded rangelands, carbon sequestration, and the protection of fragile ecosystems.

The inability to preserve pastoralist knowledge, says Tamrat: “directly impacts climate mitigation efforts… as our way of life is intrinsically tied and informs healthy ecosystems and resilient livelihoods”.

New climate reality: From technicolor Bedouin tents to ‘black box’ living in refugee camps

As the millennia-old practice of ‘transhumance’ – transiting from one pastureland to another in a seasonal cycles – steadily disappears, 38-year-old Sisay sees further alterations in the domestic fabric, which traditionally centred around mobile housing known as ‘Bedouin’ tents or ‘“buryuut hajar”, meaning “house of hair” in Arabic.

In place of their customary colorful tent, hand-woven from organic dyed wool and goat’s hair, layered with flamboyant sashes, manifold textiles and draperies, Sisay along with his wife and three children now occupy a home referred to as an “emergency unit”. This is one of hundreds of minuscule, black or white, uniformed boxes made from fodder bags and plastic scraps, pitched amidst the arid landscape of Hamed Ela, making an ‘impromptu’ settlement.

As modernity pervades everyday life, says Sisay: “[we] the ‘Elders’ notice the vanishing of indigenous art and craft”.

Sisay recalls his great-grandmother stitching applique designs in Islamic and Pharaonic style, and performing rock engravings – “often [ethnographic work] retracing our history”. Nowadays, rock engraving is rare as ‘ancestral owners’ of the technique have passed.

Part of the “indigenous mystical affair” describes Hakim, Sisay’s neighbour, is tied to a spiritual connection to the land, natural resources, livestock, sustenance, devotional dances and music. Hakim describes “the vision of the brightly colored and patterned yurts weaved by mother’s fingers herself, her most cherished hadiths [Quranic verses] engraved with finesse on the wooden bead doors”.

Perhaps no change signifies the damage to the Afar’s culture like the dying out of the centuries-old convention of camel caravans, suggests community-based teacher Mahmut.

Dating back to antiquity, caravans consist of strings of camels transporting passengers across the desert and stopping along the way at vital oases to distribute goods. More critically, says Mahmut, “it played a pivotal role in disseminating ideas in art, architecture, and religion… influencing aspects of daily life in the towns and cities of a hitherto isolated part of Africa”.

Nomads would habitually migrate in large caravans or cohorts of relatives and their extended family, occasionally converging with near kins – or voyagers encountered along the way – to live in bigger camps, before venturing their separate ways again. The freedom afforded by this way of movement enabled those communities to disperse, transmitting heritage between generations, says Mahmut, “through spreading stories, songs, dances, carvings, painting and performances”.

Camel processions are akin to a pilgrimage. They are visually evocative of the ethos of ancestors rooted in principles of exploration; hospitality; respect for all humans, fauna and flora; and a sense of communion.

As empires rose and fell, camel trains survived. But the disappearance of pastoralism and rapid-onset climate events are now rendering excursions impractical; compounded by techno-solutionism, histories of colonialism, exploitation and dispossession – all menace to undermine knowledge dissemination.

Now, anchored in one place, sedentary indigenous youth “no longer interact nor have exposure to neighboring folks,” sighs Mahmut. “Some never spoke a word in their native language.”

The native language, referred to as Afar, is an Amharic dialect. And while children are typically fluent in spoken and informal Afar, they cannot write it (although, there is no official written language for Afar). Many of the children are increasingly westernized with access to English language media via their phones, or they speak Somali as this is the predominant spoken language in the region. But the younger generations no longer speak the multiple dialects they would once have been exposed to when they missed with other tribes.

With indigenous knowledge residing in the idea of a continuum – a metaphorical passing of the torch – the Afar self-describe as “misfits in the modern state,” says Mahmut, and fear their existence could soon be reduced to, he adds: “a past civilization… a homeland of ghosts who leave no trace or borderland”.

“We feel the pain of the changes to the Land, as if pain to the self,” laments Solal, a camel herder whose ancestors go back nine generations.

Solal’s words, in the Amharic language, intimately describe the Afar’s profound spiritual connection to the land. Rock, tree, river, hill, animal, human – they subscribe to the belief that all were formed of the same substance by Ancestors who continue to live in land, water, sky.

Due to the changing climate and unforgiving weather, Solal is amongst a thousand herders and hunter-gatherers who are being pushed out of native land and forced to travel to nearby sovereign borders to scavenge for food or set camp in fixed settlement. “I don’t recognise myself in the world anymore,” he says.

By virtue of inhabiting areas that span several countries, nomadic communities often have no political rights or borders they call their own. And Afar ancestral land has always been at a crossroad of civilisations.

Now, they are facing the loss of mobility and living space; the forecast that more than 100 native tongues and their idioms will go extinct in the next 50 years; and the disappearance of invaluable methods and knowledge accumulated over thousands of years in medicine, meteorology and agriculture. The complex social and technological developments of the 21st century pose an indubitable threat to “[our] right to the continued use and restoration of [our] Land, languages and orthographies,” says Solal.

Women are 14 times more likely to suffer immediate and long-term casualty during a disaster but indigenous matriarchs’ ancestral knowledge can bolster climate security.

Near Erta Ale volcano, virtually cut off from the world and with no nearby school or other humans in sight, sisters Amina and Riwan (aged 10 and 11, respectively) spend their evenings playing with rocks and stones, making the most of what the desert has to offer.

Pictured: Amina (right) and Riwan (left)

In between playful interludes, the sisters’ day-to-day routine revolves around the basic needs of the camp: pumping water in searing 45C temperatures, foraging wood for fuel, bush clearing, weaving tapestry, or cooking at the indoor three-stone stove “to ensure our elders and brothers are fed,” explains Riwan.

Self-described “puritanists resisting sedentarisation”, the mother Eskender explains the family has elected to send “[our] three boys to school while the girls help with household chores”.

Bright-eyed and clever, Riwan anticipates (and curtly brushes off) stereotypical portrayals of African women in the Western imagination, confidently stating “[us] staying home has less to do with condescending machismo clichés imputed [on the ‘Global South’]” but rather “indigenous women’s historical role as the backbone of the labor force – it is empowering”.

“But I have dreams,” she confesses thoughtfully. From her confines, up at dawn cleaning and cooking, eating last, marrying young, the child’s story mirrors that of millions of women in matriarchal pastoralist communities in the region, whose prospects are hindered by non-existent infrastructure, poor economic development and limited access to social services such as education and health. The region alone suffers the lowest girls schooling rate in Ethiopia, with an estimated 52% unenrolled.

“Weather conditions are isolating us, while increasing the burden on women,” says 17-year-old Biruk, Amina and Riwan’s cousin. “There is little [state] support or activity in the desert,” she adds, describing how even mundane essential tasks such as fetching food or procuring medication demand herculean efforts.

Pictured: Biruk

The nearest town Mek’ele (or Merkel), the capital of Tigray further West, is situated around 780 km north of Afar land. Access to vital resources like water, wheat or cooking oil requires traveling by foot over periods of 2 or 3 days depending on conditions. “It is grueling,” says Biruk, “there is no time for enrolling in school”. Girls may also be withdrawn from education due to parents fearing danger such as rape or abduction on the commute to school. “The nearest education centers are miles away from our camps,” says Biruk, “It is a dangerous journey, with little protection or water [to keep going]”.

Gendered violence has soared exponentially to the intensity of climate shocks. Climate-induced displacements; unsafe and crowded living in emergency IDP camps; long and dangerous journeys to school; unaffordable and often inaccessible school supplies… all these issues underline the challenges and complexities of climate adaptation response, which will have to factor in gender, insecurity, pervasive poverty and socio-economic welfare.

As unpredictable natural disasters decimate infrastructure and facilities, access to basic health provisions – notably maternal, sexual and reproductive healthcare, has also been severely disrupted. Medical supplies are damaged or destroyed, while healthcare providers are in short supply, due to lack of training, lack of access and low wages.

Luliya, a 23-year-old activist for an indigenous women’s collective in the town of Asaita, decries “further critically compromised protection systems” such as emergency obstetric care “to address life-threatening pregnancy complications”, as well as insufficient “psychosocial support for survivors of gender-based violence”.

Luliya says that in the Horn of Africa alone, an estimated 13 million people are currently waiting for emergency health assistance, and more than 8 million of these are women and girls.

With the current social demands and climate changes, Luliya says pastoralism has become “irreconcilable with basic needs such as education, safety, privacy or self-development.” Mothers and daughters, the traditional primary caregivers, laborers and ancestral heartbeat that kept communities and natural resources alive for centuries, are now more-and-more opting for a part-sedentary lifestyle.

In a self-proclaimed act of resistance, says Luliya, “[Afar women] are settling in nearby villages to stock up on provisions… stash cash in [newly set-up] bank accounts, and only sporadically visiting their tribes”. The disproportionate burden on women (who are 14 times more likely to be harmed during a disaster) – and resulting fracture in social contract – “bears wider, disastrous implications for our way of life, and collectivity at large,” says 11-year-old Riwan, astutely.

In a continent where 60% of women are employed in agriculture and produce 80% of Africa’s food supply, Riwan says: “The world will soon mourn our hegira [Arabic for ‘mass departure’]” as the loss of “the fiber and strings of humanity, and on which livelihoods and resources depend”.

Historically, women are the pillar of Indigenous social institutions and knowledge transmission, with their daily contributions spanning from working in the fields, growing food, educating younger generations and teaching them how to preserve their natural resources, to arts and crafts, weaving, singing dispute resolution rituals and producing herbicidal medicine. So, women’s unfulfilled potential puts Indigenous legacies at risk.

Riwan’s proud father, Darwit, says: “The masculine views the feminine as a blessing… the key to adapting and creating resilient communities.”

Water as a strategic war resource

Wearing a traditional Habesha robe and a knock-off American skateboarding shirt, and gripping a Kalashnikov in his hands, a young Afar boy named Tifa, is a visual mosaic, displaying how modernity, climate change and warfare are affecting people here. “Water scarcity is exacerbating armed violence in the area,” he shrugs before chatting into his walkie-talkie to fellow fighters posted at the far end of the road bend.

The Danakil region has been torn apart by the Tigray war between, on one side, the Ethiopian and Eritrean governments, and on the other, the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), a branch of ethnic nationalists seeking independence from Ethiopia for the Tigrayan people.

Since erupting in November 2020, the conflict in northern Ethiopia has killed thousands of civilians and forced an estimated 5.2 million people from the Tigray, Afar and Amhara regions to flee into Sudan and neighboring nations. Despite a peace deal to halt hostilities, affected populations – mostly women and girls – remain in dire need of humanitarian assistance as pervasive poverty, increasing climate emergencies and conflict are disrupting aid.

“The drought has affected all of us severely,” says Kesagi from the Elele district. The matriarch, aged in her eighties, recalls happier times “caring for hundreds of goats” but due to ecosystem upheavals and “retaliation from enemy tribes,” most of her animals have perished.

The armed group Al-Shabaab, which operates in Western Tigray and neighboring Somalia, deters parents from sending their children to search for grass or to walk livestock due to the danger of abduction or assassination. “My family hides in the desert away from the battleground towns of Aato, Yeed and Washaaqo… hence, access to water is once every four days,” says Kesagi.

Inter-ethnic rivalry traces back to imperialist Ethiopia in the late 1930s, and the rhetoric of Italian fascists which fomented discord to undermine collective resistance.

“Knowing that Ethiopian unity helped us defeat [colonizers] at [the 1896 Battle of] Adwa, they set to divide Ethiopian nationhood,” says Birhanu Bitew, lecturer in Political Science at Debre Markos University, referring to Mussolini’s propaganda in the 1935 Abyssinian crisis which “re-imagined” the state of Ethiopia as a mere collection of discrete ethnic groups dominated by the Amhara ruling class.

Bitew says: “The Ethiopian royal family – the elite – descends from the Amhara… hence colonizers ingrained the belief that the diverse people of Ethiopia were economically exploited and culturally marginalised by ethnic Amhara, with the support of European powers”.

Communities in this region, says Bitew, went from peacefully coexisting as semi-autonomous tribes to becoming polarised and seeking liberation from Amhara colonial oppression, whether real, designated or perceived. “All is the product of colonizers,” Bitew says, “they introduced the concept of tyranny in Ethiopian political vocabulary to split and control us.”

People’s resentment, these days, they say, ties less to by-gone conquistadors rationalizing their presence under the falsely altruistic pretext of “anti-Amhara political mobilization” and “national self-determination of the Oromo and Afar”, and more to the “continuous, opportunistic abuse of our political, cultural and natural resources” by these same global hegemonies.

One member of a pro-TFLP youth militia (who wants to remain anonymous), says: “The ethnicized narratives imported by foreigners laid the seeds for large-scale genocides [perpetrated by all parties]. And now, [the people’s] social and environmental well-being suffers the price of extractivist greed.”

Non-Amhara are reluctant to revisit the possibility of their past involvement or inaction in the systemic, decades-long massacre of the Amhara since independence. According to a 2023 national census analysis, more than two million Amhara could not be traced, including 100,000 killed or evicted (due to climate) from provinces in the Tigray region since the onset of the civil war.

The tragi-comic of Tifa, the prepubescent Afar fighter armed with a rifle almost as big as him, effectively captures the destructive relationship between land, sovereignty, the danger of national myths in identity formation, the power of ethno-nationalist grievances, and the resulting political unrest, conflict, migration and gender violence.

“A full-scale humanitarian crisis further compounded by cataclysmic climate conditions” notes Kesagi.

The changing ecosystem is driving need, but the protracted war is “diverting already-scarce resources away from mid- and long-term investments in education, food security, gender and health assistance”, portends Luliya, spokesperson for Asseita women’s collective.

The disappearance of the ancient salt trade

Lake Karum is one of two salt lakes in the northern end of the Danakil Depression. It resembles an Arctic desert more than a lake, but it remains liquid despite the heat due a system of hot springs and steam emanating from the nearby Erta Ale volcano, which rises in the southeast.

The lake-bed consists of a jet-white salt crust checkered in irregular contours, and which slowly becomes submerged in the clear water. The transition from salt pan to salt lake is gradual, as the pan starts to shimmer and shine as it jets off into the sunset. The next morning, the water will evaporate again at a prodigious rate, powerless against the blazing sun, leaving behind ever-valuable salt crystals.

For centuries, the Afar have eked out a living by extracting salt from the mineral laden lakes in this remote corner south-east of the Danakil.

Every morning, hundreds converge on a dry lakebed, where they cleave the ground open with hand axes, just as their fathers and grandfathers once did. Caravans of 15 to 20 dromedaries, each carrying dozens of salt bricks weighing an average 4kg, then embark on an 80km expedition through the desert to the small hamlet of Mek’ele – where salt is parceled out to traders.

But this ancestral tradition, which historians estimate has gone on since the 6th century, could soon be lost.

“Salt trade is physically taxing,” says 28-year-old miner Yonas, standing on the cracked earth that fringes Lake Karum. “Workers rely on basic picks to chop chunks of salt… in extreme temperatures that can reach +50C.”

For a paltry 150 Ethiopian birr (£5) a day, miners have also grown tired of the industry’s backbreaking labor and meagre wages. Once vital to the economy of the depression, salt is no longer the currency. “I am struggling to afford rent,” confesses Yonas, who lives in a ramshackle settlement of huts in Hamed Ela near the salt fields.

“It is not just nature turning against us,” adds Fikru, another worker. The region has also attracted the foreign firms hoping to mine potash and send it to Asia. “[In comparison] our manual way of mining takes more toil and time,” he concedes. As technology puts further pressure on tradition, he predicts “plant operations will take over one day as the main supplier of salt in the area.”

The Ethiopian government has been expanding its dam building projects and cutting new roads through the surrounding mountains in a bid to open up the isolated northern region to investors. Salt-laden camels, once the only viable way to navigate the four-day trek down the rock-strewn gullies from Lake Karum to Mek’ele, may soon become a relic of the past.

Now, trucks pick up the salt loads from Berahile, a main salt trading outpost which connects to Mek’ele by asphalt tarmac.

The journey takes only three days, an improvement camel drivers and labourers have welcomed while simultaneously worrying that they will soon be put out of business. “Machine has replaced us in the fields… infrastructure progress has rendered camels obsolete,” says 53-year-old veteran miner Idriss.

Inextricably tied to indigenous culture, camel expeditions in pre-industrialisation times, helped establish profitable commercial routes across an extensive network linking China to Europe and North Africa via the Middle East.

The shift has constrained multi-generation camel herders to take up menial jobs, loading onto trucks the approximately 5,000 salt bricks that arrive each day at the trading posts.

International aid is failing Africa…and indigenous science may be the way

Ethiopia’s crisis is multifactorial. Drought, conflict, the economic fallouts of the war in Ukraine, and supply chain disrupted globally are all straining Ethiopian government resources and limiting what it can deploy to address the growing food insecurity crisis, acute poverty, war crimes and sexual violence.

The International Rescue Committee (IRC) estimates a humanitarian response would require $1.6billion. Yet, by the end of last year, less than 42% of this was funded, including UNICEF’s appeal for children which remains only 38% funded.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) is coordinating 262 partners to reach 21.5 million people across Ethiopia, Sudan, South Sudan and Somalia. Over 88% of people in drought-affected areas have yet to be reached with health services, while more than 70% lack access to water, sanitation and hygiene assistance – all of which are critical in curbing mass deaths during a drought and cholera outbreak.

Despite being Africa’s second most populous country, poverty remains rampant with two-thirds of citizens living below $1.90 a day.

Foreign aid as currently practiced in Africa has failed to achieve poverty reduction targets or sustain economic growth, observes Dambisa Moyo, head of economic research for sub-Saharan Africa at the World Bank. It is the only continent where official aid inflow outstrips private capital inflow by a large margin. In 1970, Africa was home to 10% of the world’s poorest people. Yet, today, the continent is home to more than 75% of the world’s poorest. And forecasts suggest it could rise to 90% by 2030.

Africa’s aid-dependent economic model “provides free money… when countries should be incentivized to take advantage of opportunities provided by the global economy” Moyo notes. Misallocation of resources, corruption and bad governance “further limit the continent’s ability to use aid efficiently and paralyse social development”.

“The region remains in dire misery… exposing the true scale of the Global North’s economic appropriation of the South,” says miner Idriss. In 2015 alone, the Global North net appropriated from the Global South 12 billion tons of raw material, 822 million hectares of land, 21 exajoules of energy, and 392 billion hours of labor, worth $10.8 trillion in Northern prices – enough to end extreme poverty 70 times over.

As Ethiopia faces increasing debt, its economy ruined by inflation – and the associated higher governmental instability and civil unrest – indigenous, social and climate activists demand “restoration for loss and damage” caused by the wealthiest 1% of humanity “who alone are responsible for twice as many emissions as the poorest 50 per cent”.

The message of the Afar people of this region is that it is morally incumbent on the privileged to safeguard their economic and political rights. Rather than keep Africa “enslaved to foreign aid”, civil activists call for utilising existing socio-economic structures rather than “top-down policies”, including relying on valuable indigenous science “which can help revitalise practices and technologies connected to natural resource management” argues Moyo.

To settle the perennial debate, I turn to the wisdom of the people, those at the receiving end of foreign aid. I prompt tribe-chief Aboubakr on colonial legacy, economic monopolies, capitalist greed – and the profound implications for the continent. Toiling from under the gaze of a caravan of camels, he describes conflict, power and greed as “little Earthly affairs”.

Through the wise eye of the Amharic people, the cycle of metamorphoses in the continent’s topography, space and shapes are a reminder that, as Aboubakr, says, “the beauty of Mother Earth is in the alchemy that is in the transient nature of life and all her creations.”

A reminder of Mankind’s cosmic insignificance.

All images by Soukaina Rabii.