“He was drowning in facts, yet knew little about the human tragedy of unemployment, what it was actually costing in terms of broken families, alcoholism, disease and hunger. He wanted something more, something intangible and descriptive, something that would tell him what it felt like for a man to lose his job, his savings and his house and to watch his family sink into misery. Only then, he said, would he really be able to take the pulse of the country and devise a sound relief programme for the ‘third of the nation’ that was ‘ill-nourished, ill-clad, ill-housed.’”

Caroline Moorhead, (Introduction to The Trouble I’ve Seen, by Martha Gelhorn)

The above passage is an account of Harold Hopkins’s response faced with running one of the largest public employment programmes during America’s Great Depression. The New Deal administrator eventually sent out a team of journalists, economists, and novelists, “all people accustomed to listening to what people said” across the country to places where poverty and unemployment had destroyed lives.

This method of using individual stories to influence political policy continued into the thirties with the Federal Writers Project, which spawned oral histories, photography and essays, all documenting the social scars left on different communities by economic crisis. These programmes also formed part of a wider literary movement, where the voices of those usually silent took centre stage. John Steinbeck, Zora Neale Hurston, Saul Bellow, Richard Wright, John Cheever, Ralph Ellison are some of the now revered authors who took part.

Who will capture the reality of lives disrupted by the latest Great Economic Crisis? Politicians still drown in facts and statistics, even more so than they did in the 1930s. And the government appears content to devise austerity policies regardless of the experiences of the poor and the marginalised. However, writers and artists are interested, they are listening, and many are voicing the complex array of experiences under austerity.

This week’s edition of Lacuna explores the impact of this work on the debate around austerity. In his affecting review of Clio Barnard’s 2013 film The Selfish Giant, Chris Davis begins with a reflection on his time as a teacher at a Nottingham secondary school. Many of his pupils arrived at school hungry and unkempt leaving him “deeply saddened” and “quietly troubled”. The lack of language to describe such modern want, without descending into grotesque caricature, added to his unease. But in The Selfish Giant, he finds two teenage characters, growing up in an impoverished area in Bradford who resonate with him profoundly. Their stories provide a powerful portrait of social deprivation and “shows us what happens when one is driven to trading in an attempt at mere survival”.

Illustrator Linnéa Haviland also amplifies the voices of young people. Since 2010 a series of policies, particularly the scrapping of the Education Maintenance Allowance and the increase in university tuition fees, has made it difficult for many young people to imagine a prosperous future. The alternatives to further and higher education are just as bleak. Armed with a sketchpad and pencil, Haviland spent time with children at a youth club in Peckham, South London. Her drawings capture the transient dramas of childhood interspersed with real concerns about the future of the club amid spending cuts and the dangerous gaps they could leave behind.

Dallal Stevens also defers to the young in her introduction to Into the Fire, a documentary about refugees and migrants living in Athens. “I look around at the 50 expectant young faces – all men and women in their early twenties…what has attracted them to the study of refugee law?” It will be these young people who will have to unravel the deadly legacy of our current crop of politicians. Into the Fire reports the human reality of this legacy; racist groups randomly attacking anyone they believe is a migrant or refugee, the cruel indifference of those administering Greece’s asylum and immigration system and the destitution in which many are forced to exist.

Poetry can also be a powerful tool for holding power to account when human rights are abused, says Laila Sumption. Sumption chose three poems for Lacuna from the anthology In Protest – 150 poems for human rights. Each vocalises the lives of the unheard and the isolated, in Paris, Kolkata and China. The dry economics of inequality and poverty are brought to life with poignant imagery and clear, simple language in these poems.

When considering how we capture the reality of lives disrupted by a sustained programme of austerity, one might point to Nathan Filer’s award winning novel The Shock of the Fall. It tells the story of Matthew Homes, a young man with schizophrenia, struggling to navigate a chronically under-resourced mental health system. However, in his article for Lacuna on the process of writing the book, Filer reveals that the novel is not overtly about “the failings of mental health services”, though he has criticised spending cuts in other writing. The focus instead is the personal story of Matthew. This zoning in on human stories is something that is lacking in the public discourse on austerity. It is something that Harold Hopkins believed would better help him “take the pulse of the country and devise a sound relief programme”. Faced with growing inequality, job insecurity and poverty, perhaps it’s time this government started to listen to the stories of those affected.

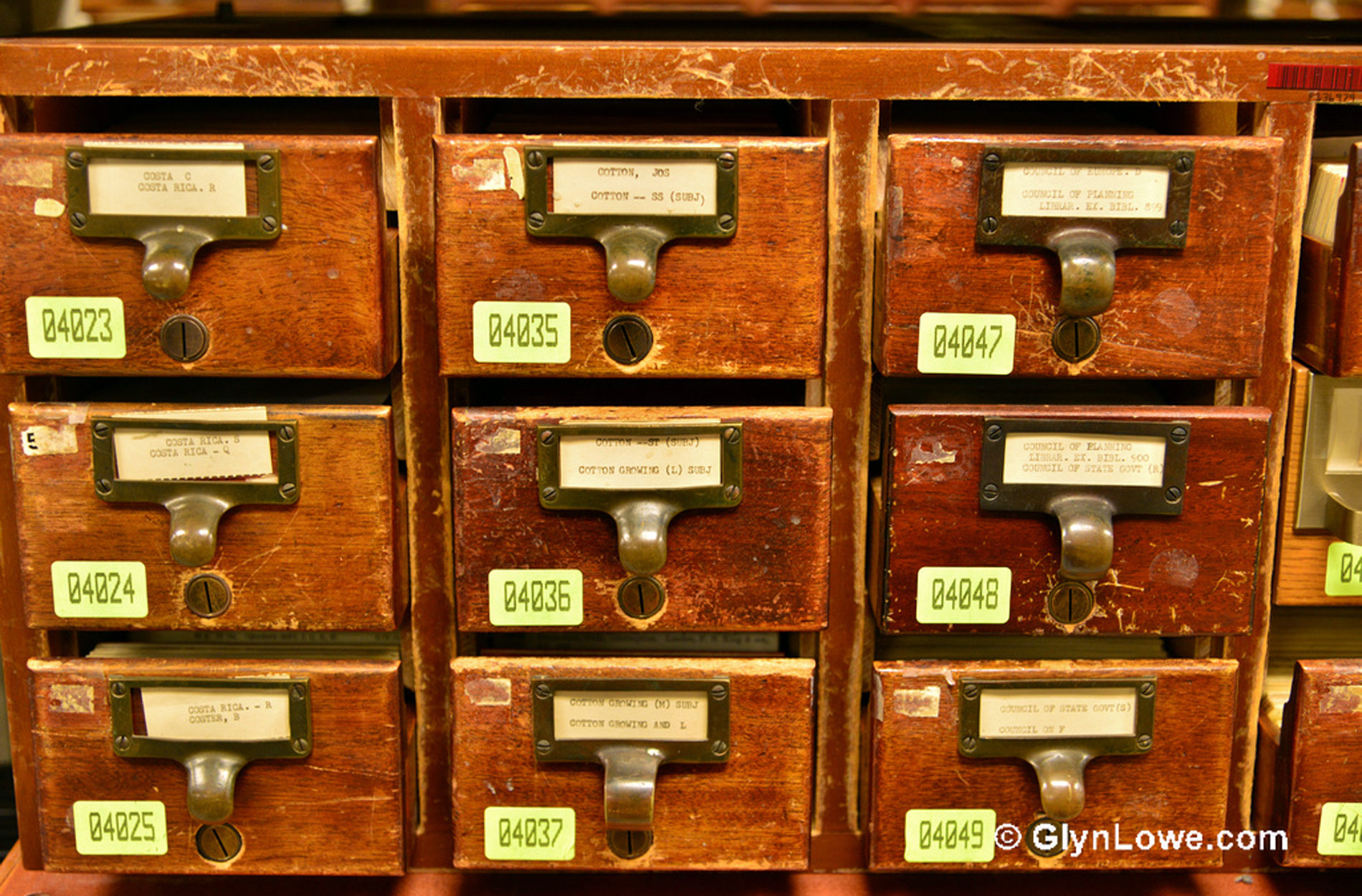

Photo from the Washington Library of Congress collection![]()