Christopher Davis reviews recent works on conflicts in the Middle East, with an emphasis on Gaza, trying to understand how we might see them through the eyes of others, looking at the everyday and the ordinary to salvage something understandable from the chaos of violence.

A Review of Je Veux Voir (2010) a film by Khalil Joreige and Joana Hadjithomas, Occupation Diaries (2013) by Raja Shehadeh, and The Book of Gaza (2014) a collection of storiesedited by Atef Abu Saif

I

In the opening frame of Khalil Joreige’s and Joana Hadjithomas’s film Je Veux Voir (2010), Catherine Deneuve stands by a window overlooking Beirut while a conversation moves along out of shot. We quickly pick up that the discussion taking place is a cagey one between the two filmmakers and Deneuve’s people, so to speak.

It’s really too dangerous. It’s not what we had planned. It’ll be a simple, quick shoot. We’ll go to the South this morning and be back by evening. But what for? Why take such risks? Catherine will go to the South with Rabih Mrouré, our favourite Lebanese actor. They will go through the post-war region and we will film, it’s as simple as that.

All the while Deneuve goes on listening, still eyeing Beirut moving down beneath her gaze. And then she cuts in: Je veux voir. I want to see.

Moments later we are watching the two of them – Deneuve and Mrouré – as they embark upon the stilted beginnings of a relationship, the latter driving them both in a dusty looking Saab through the Lebanese capital.

I didn’t get your name; there was a lot of noise outside. Rabih. Rabih. The “r” is rather difficult in Arabic. Rabih. Rabih. Rabih.

They seem unsure of what exactly is happening. We watch them through the windscreen from a camera seemingly mounted upon the bonnet, in a style we have seen on film before so many times. But where we might recall elsewhere the superimposed backdrop of moving traffic through the back window, and the driver’s hands unconvincingly rolling from side to side on the steering wheel, making it clear that the shot is staged, here Rabih is driving for real. The angled glass reflects the Beirut skyline as it streaks past, so that we can see driver and passenger, and what they both see, in a sort of dreamy montage.

The film is a patchwork, a monument to a mantra: it doesn’t matter what comes of it as long as we give it chance. Sometimes we are apparently watching a scripted scene between two seasoned actors – Deneuve always demure, Mrouré enigmatic. At other times, it would seem that there is no script at all. And there are moments when we are caught somewhere between. In any case, the film proceeds in this uncertain manner – always unsure of quite what it is meant to be doing – but held together by this planned journey southwards.

Lebanon’s border with Israel is fragile. A 2006 conflict waged between Israel and Hezbollah, a militant Islamist group based in Lebanon, found its epicentre along a border that stretches from the Mediterranean in the west to Syria in the east. The consensus is that the month-long conflict began after a Hezbollah offensive against Israel, which was then greeted with force in return. Casualties numbered somewhere close to fifteen hundred, the vast majority of whom were Lebanese. Je Veux Voir is not concerned necessarily with unravelling the knots of these circumstances, of investigating the workings of the war. Conflicts in the Middle East often seem to be characterised so often by this sense of indefinability, and perhaps suffer as a result of this. The terms of the debate are contested for so long and to such lengths that the whole thing loses sight of itself, while casualties continue to mount.

What is missed when wars are represented only by numbers, made visual only through images of suffering and wreckage, is the smaller details that simply cannot compete on the same scale.

What is missed when wars are represented only by numbers, made visual only through images of suffering and wreckage, is the smaller details that simply cannot compete on the same scale. I am not thinking only of the more everyday characteristics of daily life that we fail to see when faced with grand-scale depictions of war – that moment when a screaming, contorted on-screen face gives us a sense of outrage, but in its very crudity stops us thinking of the ordinary person it belongs to. More than this, watching from the outside we might also forget that the landscape itself goes on living in perpetuity, even as – and after – it is battered and bruised. Joreige and Hadjithomas restore this oft-lost dimension, hitting upon small rhythms of the Lebanese landscape. Minute-long panoramic shots across lush green hillsides give us chance to watch as cars snake slowly across. We drive along the edge of a wheat field for what seems like an eternity, watching the little heads disturbed in gentle waves as the car blows on by. For a time, the bonnet camera, dipping and shuddering in turn with the bumps in the road, follows a motorcycle upon which two men perch, gesticulating in conversation with one another. It is nothing and it is something. What we are watching more often than not provides not context, at least not in a socio-historical sense. But it gives us living backdrop.

When the convoy – the Saab followed by the filmmakers’ car – reaches the Lebanese south, the building Rabih tries to find, the abandoned former home of his grandmother, is no longer there, not in any recognisable sense anyway. After a time he does manage to locate it in earnest, but the village in places has been twisted hugely out of shape. From back at the car we observe Catherine observing Rabih observing a changed landscape, and it is difficult to know what to think. And so it should be.

The film comes to us in fragments. There is meaning to be had, but it is not packaged for us. We are left with half-thoughts, and a great number of them; but rarely do they come to us fully furnished. An extended shot of Rabih walking down through the village gives enough time to fully consume the scene. We can make out individual bricks, hear the hiss of a lorry coming to a halt somewhere out of shot. Deneuve waits in the car, rising up in her seat and peering through the smeared windscreen down to him. Later, as the two walk silently around, Deneuve always glancing across at her counterpart, we see in the background two workmen seemingly rebuilding a house, a rickety wooden ladder leant up against a wall. It does not feel like some narrative of hope, though – for one, the moment is barely registered on screen. No, it is a simple observation: buildings are damaged, buildings are rebuilt.

Everything about the film is so exploratory, always playing out as though scientifically testing what might yield something of worth. There is no noticeable aesthetic; it has the untidiness of a scrapbook. Some shots are vast poetic affairs, others almost bare. Some are sprawling, some clipped to a mere second or two and no more. Watching Deneuve, too, and her stream of sultry glances, the likes of which have been so iconic in circumstances much removed from these, we get the sense that she is feeling her way through it all in the only way she knows how. It all seems as though no one, neither cast nor crew, knows quite what to expect. (Of course, if I am mistaken and everything is delicately and painstakingly scripted, it could be either a masterstroke or a failing – there is no way of telling.)

The upshot, though, is that Je Veux Voir appeals to a part of us that does not wish for wholes. Instead, we feast on throwaway scraps, and do so relishing each one. It is in many ways just a repackaging of important questions, and a much grander equivalent to pointing a camera at an infant and hoping for something funny or endearing to materialise.

In all of this I am not suggesting that the film stops short of yielding meaning; or, on the contrary, that it signals a new beginning for cinema. It is perhaps simply that this landscape, so pulled from pillar to post and unsure of itself, is not underwritten by any solid narrative. There are few familiar tropes to fall back on in circumstances like these. As an Englishman, my green and pleasant land is always a comforting and enduring myth, no matter how weak my patriotism might be. I would always have green hills and coastal towns as a contingency plan. Je Veux Voir, though, speaks of contemporary Lebanon in different terms. In every sense, people do not know where they stand. To walk the landscape is not a grand tour but a piecemeal education.

II

The day I most dread is not the one that will prove to be my last, but the one in which I can no longer see the poetry. If there have been times when it seemed as though there were no greater sadness possible, I have from somewhere seen poetry in the bleakness. Likewise, if I have ever felt anger so acute that I might unravel, I have drawn – even if only much later – from the ferocity of it. I fear a day upon which my heartstrings could not be pulled, and when I could no longer be moved to take up a pen.

Raja Shehadeh, a writer who possesses his own fair share of anger, puts it somewhat similarly. ‘I don’t want to…become like those old men who stand passively smiling and caring most about the state of their health and preserving themselves, as though they were all that mattered in the world. I want to continue to feel the anger and to rage, rage against the dying of the light.’

Shehadeh’s anger is not a simple one, and it appears more difficult still for him to resolve it. It is fiery and easily fanned. The question of Israel-Palestine is difficult to find answers to, it seems, for insiders and outsiders alike (although for different reasons), particularly so in light of the latest swell in the conflict. Occupation Diaries predates by a year this summer’s escalation in violence, but does a good job in shedding light on it. Not only in the circumstantial evidence it gives us about Israeli-Palestinian relations, but also in the sense that it gives little anecdotal glimpses of the way that things in Palestine work, glimpses that start to illuminate the subtlety and the sensitivity of it. Early in the book, for example, we are told about the plight of Shehadeh’s driver and friend, Hani, whose brother’s murder has been unresolved for eleven years. The victim had been killed when a passenger in his car, who turned out to be a Jewish American, had shot him in the head while they drove through Jerusalem. Despite seemingly strong evidence, the Israeli police had kept Hani and his family waiting on any closure for the next decade. ‘How can I ever forgive them?’ Shehadeh asks. It feels like an everyday occurrence.

‘With every new war a new book,’ we read. ‘Five wars, five books.’ In light of what has been written so far, it seems to me only natural that such a pattern should emerge for the author, who counts the Second Intifada, the Israeli invasion of the West Bank, the Iraq war, the Lebanon war of 2006 and the war in the Gaza Strip in his quintet. Writing is all at once a coping strategy, a vocation, and a way of finding self-understanding. Occupation Diaries consists of diary entries written by the author in the two-year period leading up to Palestine’s bid for United Nations membership in 2011.

This much can be noted with authority: the book recounts Shehadeh’s comings and goings during that time, his engagements with old friends and allies, his encounters with filmmakers and politicians. It is a biting and honest account. It is a book I enjoyed reading and which gave depth to my knowledge of Palestine. Beyond this, I find I have a certain difficulty writing about it. More generally, I find it difficult to write about the region – and I imagine that I am not alone in this. Writing the Middle East is so difficult at present. There are so many lenses, so many degrees of abstraction. It can be testing to pick out an individual voice in a raucous crowd of shouts. Some might say, as though to drolly emphasise their point, that the Middle East is a minefield. But that is precisely the problem. To try and understand events as they develop invariably involves attempts to nail down facts and weave together narratives that are coherent. Therein lies propaganda, political interests to serve, the thorny issue of diplomacy. The reality on the ground is easily missed. The small rhythms. Knowledge is highly priced and fiercely competed for. Writing the Middle East seems to be a discipline in its own terms and is defined by impasses.

There are so many lenses, so many degrees of abstraction. It can be testing to pick out an individual voice in a raucous crowd of shouts.

Shehadeh is no stranger to this himself and bemoans the ‘corruption of political language’ in the region. At one juncture he reflects on first seeing the Oscar-nominated film, Ajami (2009), and the anger he feels at its ‘ideological underpinnings’, its screaming silences and sub-texts. It is a wider phenomenon, one feels. There is genuine irritation in the tone of the passage. ‘The film offers no possibility of redemption or hope,’ he writes. ‘Its subtext is that since the Arabs are so murderous, Israel is left with no choice but to oppress them and build a wall inside the West Bank to divide the civilised from the savage.’ Later, something similar occurs in relation to a piece of his own work that is earmarked for a stage adaptation, one that would appear in Israel. The play would be state-sponsored. Shehadeh has concerns about losing the integrity of his work as it is passed into strange hands. ‘The meeting ended without a resolution,’ the reader is told. ‘I needed a few days to think about it.’ The next entry comes five days later: Shehadeh cannot bring himself to do it.

The book is not short on astute commentary, telling anecdotal evidence, and ruthlessly delivered criticism of Israel’s ongoing political behaviour. I stop short of lifting and recounting examples here simply because to do so would hold up the book in a way not in keeping with its overarching spirit. Statements of a political nature are pristine and obdurate when given in isolation. Shehadeh is not only a political writer. The book is a diary, and part of its strength as a cohesive piece of writing about Palestine is the way in which it is subject to the meandering patterns of daily life. How much more telling a scathing passage is rendered when it comes with personal context. The turns the author takes, through belligerence and despair, contentment and dejection, give us some idea of his daily Palestinian life – as an existence full of contradictions and inconsistencies.

And that is how I feel we are best to read Occupation Diaries: as a deeply personal account written by someone whose impassioned opinions are equalled by his wish for normality in the Middle East. We should not lose the humanity of the book by concentrating only on its politics. For me, what stays with me more than anything after reading the book – or, to put it differently: what brings the text together – is Shehadeh’s heartfelt feeling towards Palestinian soil. Not in an abstract sense, but in the very manifest brown matter beneath his feet. He is a keen gardener, and the trope comes up repeatedly throughout the book. (Any reader who arrives here on the back of reading Palestinian Walks, the author’s Orwell Prize-winning book, will already know of his affinity with the landscape of his homeland.) It is perhaps unsurprising that this should be the case when one considers that the nature of Palestinians’ grievances relate to issues of land ownership. That said, Shehadeh’s tenderness towards the soil has more subtlety about it. The book is punctuated by passages delighting in the lay of Palestinian land and particularly, in a more personal sense, the lay of his own garden.

Gardening grants time for reflection, it would seem, grants Shehadeh perspective. He writes of his garden as though it were an organ to be either cared for or left to die away. It is linked inseparably to his happiness.

‘Today I sat for a long time on my back porch overlooking the garden, with the dappled light coming through the gazebo covered with wisteria. The garden is just glorious, with colour everywhere, and plants hanging so naturally and looking as if they utterly belong there. I have finally learned what works best for my garden. I managed to plant cyclamen between the rocks that surround the raised earth around the trunks of the olive trees, and they’re doing splendidly, sprouting out the rocks like candles. The weather is superb, and the whole place cooled by the gentlest breeze. The only sound throughout the day has been the chirping of birds. It started in full force early in the morning, when I woke up after a long night, having gone to bed all too early, and has not ceased. I want for nothing more on a day like this.’

The garden is an apolitical space, one of leisure, but also one of productivity. Later in the book, Shehadeh writes of the crops the soil yields – thyme, parsley, winter vegetables and olives – and it rings out like a joy incapable of being dampened by anything that is happening beyond the garden fence.

Something resonates with me about the innateness of the logic of gardening. It is primordial and there is refuge in it. To call it life affirming sounds too grand, but it has something of that sentiment. I planted an apple tree four years ago and this summer the young sapling bore fruit for the first time: big, oddly shaped waxy apples that are a touch bitter on tongue. There are only four or five, barely enough for a pie. It does not matter, though – I am happy. They started as little pink-tinged buds in the spring and now, six months on, they are ripe for picking and eating. It is not a matter of sustenance, but something to do with the faith we can invest in the certainty of nature’s enduring cycle, even if our faith wanes elsewhere. Gardens are resolute and full of character. They grow unruly if left alone, but at the behest of our hands can be guided gently and made beautiful. They outlive us. They speak a common language.

While it might seem obvious, Occupation Diaries is a book to be read in a manner wherein the reader never lets go of the image of the pen clasped within the author’s hand. The hand that writes is the same hand that tends the soil is the same hand that holds the steering wheel of the car that traces lines across the Palestinian Territories. Read with this in mind, it is possible to see the way that politics in the region sits alongside everyday life, and that Palestine is not only a political landscape. It is a book to drift through, the reader taking the time to follow its course of days and weeks, and its rolling waves of feeling. It is stronger not in nailing down arguments (which, incidentally, it does pretty convincingly) but in opening out a landscape – something that feels far more fruitful. I have suggested that the book is difficult to write about. That is only because I want to resist treating it as an authority on Palestine. It amounts to more than that. It is not an extraordinary book; it is an ordinary book in many ways. And that is its strength.

III

Late in the days of South African apartheid, the publication of an essay by Njabulo Ndebele lamented black writers’ unwavering inclination toward the representation of spectacle. He writes: ‘The visible symbols of the overwhelmingly oppressive South African social formation appear to have prompted over the years the development of a highly dramatic, highly demonstrative form of literary representation.’

To his mind, all that was familiar in the everyday life of the African – mass shootings, the passing of draconian laws, forced removals, the economic exploitation of workers, the luxurious lifestyles of white South Africans – all of this led the black writer inexorably into an unbreakable bind with the spectacle.

Ndebele saw that the short story, the mainstay of the black literary scene in the apartheid years, was damagingly trite. Everything in it was signposted, he suggested, pointing towards what he called the ‘complete exteriority of everything’. The spectacle invariably took precedence over all else, with nothing left to chance. As a body of work, it was protest literature, writing based on the logic that the more brutal the depiction of the violence, the better. ‘No interpretation here is necessary,’ Ndebele writes, ‘seeing is meaning.’ The upshot, then, was that this literature could have no greater claims than the representation of spectacle. It delivered its message demonstratively, straightforwardly, and left no room for anything more.

Ndebele’s recourse is towards what he terms the ‘rediscovery of the ordinary’; that is, the antithesis of spectacle, which he imagined would pave the way for the growth of a consciousness. ‘The ordinary is sobering rationality; it is the forcing of attention on necessary detail,’ he writes.

Comma Press

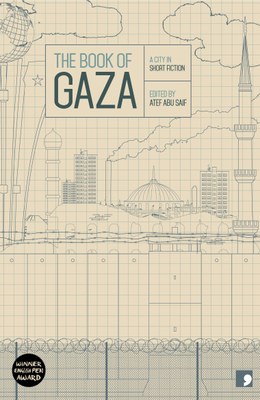

The apartheid literary lineage traced by Ndebele in his essay finds an historical counterpart in Palestinian writing over the same period. In the introduction to The Book of Gaza: A City in Short Fiction, Atef Abu Saif recalls those same years – the 1960s and 1970s – and a literary culture in Gaza that was similarly characterised by concision and an unrelenting lens on issues of the nation. The echoes of Ndebele are difficult not to hear in Saif: ‘[The short story] shed light on simple characters, people living in camps and in the neighbourhoods of Gaza City, overcome with hardship and suffering, yet filled with determination and defiance.’ That changed in time, Saif suggests, with a later generation becoming ever more ‘attached to their inner worlds.’ But one imagines that inclination towards the dramatic, when it is so commonplace a presence, must remain strong.

Just as in South Africa, the short story has assumed an important role in the cultural history of Palestine. And, as Saif suggests, Gaza itself has for centuries ‘had a central place in the literary life of the region’. The short story is a form that has been able to cope best with the strictures of censorship; it can be written on the wing. And, as a latter-day endorsement of Ndebele’s sentiment towards his apartheid-era homeland, I too look to this return to ordinariness in the short story – more than ever given the current circumstances – to help buttress our collective understanding of Gaza. And The Book of Gaza does to an extent make that much-needed commitment to the ordinary. Its contributions, ten short stories spanning a three-decade period beginning in the early eighties, help to add depth and texture to our conceptual mapping of the territory.

‘The ordinary is sobering rationality; it is the forcing of attention on necessary detail,’

Again, it feels difficult to discuss the book as an entity, as an authority – the themes it touches upon are so broad, the prose so varied from story to story, the background circumstances so different from one to the next. Throughout, there are moments that have us prick up our ears, little pithy state-of-the-nation signposts. ‘Gaza was hard on her,’ we read in the opening story, ‘Journey in the Opposite Direction’, one of Saif’s own works, which sees the unexpected coming together of four characters in a café in the southern city of Rafah. ‘It was hard on her constantly.’ And later: ‘Gaza is just a big prison.’ But elsewhere, Saif’s writing is delicate and appeals to us somewhere deeper. Toward the end, the four characters push back from their café table, take to the car, and head northwards by night to Gaza City.

‘The moon escorted them, as though to protect them from the phantoms of the night. The lights of Gaza City began to appear from behind orange fields when Ramzi suddenly cried, “The moon has disappeared!”

Samah laughed: “Who’s stolen the moon!”

Ramzi stopped the car and the four of them got out, drunk on the beauty of the moment as they searched the sky for the moon. It was veiled behind a bank of cloud that was gathering above Gaza. Samir suggested that perhaps the moon had decided to remain back in Rafah. “I saw it just a short while ago, near Deir al-Balah behind the date palms.”’

It is much easier to discuss the book as an experience. We sail through these passages from story to story gathering images and symbols – truisms – along the way. Saif’s moon-scene, here. The image of a young veiled woman sprawled out and fantasizing in the privacy of her darkened Gazan bedroom, conjuring up images on the walls, in Naajlaa Ataallah’s ‘The Whore of Gaza’. In Mona Abu Sharek’s story, the phrase: ‘Passion in a rational heart is a mythical idea’. And, in Asmaa Al-Gul’s, the narrator’s invitation to the reader to join her on the walk to university, a route along which she counts relentlessly: ‘I count every contiguous and incidental thing: successive drains (like I’m doing now); the storeys of buildings, their windows, balconies, electricity pylons, the doors of closed shops.’

One short story alone cannot frame the whole picture; and when it tries to do so, it is perhaps to its detriment. But from this series of stories read together we as readers are well placed to pick up snatches of meaning, glimpses of life, fragments that merge clumsily together to become constellations of personal knowledge. That South Gazan night-scene of Saif’s has stayed with me enduringly. (So, incidentally, have the twinkling lights of Beirut, Shehadeh’s blossoming Ramallah garden.) It comes to mind whenever I now hear the word Gaza, along with other little signals and pulses that I have picked up en route. All this that I recount here is not one sole strategy for understanding Gaza, Palestine and the wider region. But it forms a complementary part of a larger process of individual discovery. No single voice can gives us answers, for there is never objective truth in it. It is up to us to stitch together our own patchwork.

No single voice can gives us answers, for there is never objective truth in it. It is up to us to stitch together our own patchwork.

How double-edged the timeliness of the Gaza anthology is. Published only in April, there was no way of foreseeing the sudden unravelling of Israeli-Palestinian affairs over the summer (although, of course, one might well suggest this such a thing seems always foreseeable). In early June, the kidnapping of three Israeli teenagers in the West Bank quickly escalated to the level of airstrikes, such are the precariousness of relations. While the ensuing conflict mobilised debate the world over for a month or more in July and August, the situation then seems to have slipped from view somewhat. Images of Gaza explode in great dazzling clusters. And just as quickly they are gone.

This is a collection that contains within its pages a more subtle thread than what we – that is, those of us who do not know the feel of Gazan soil beneath our feet – are used to, which is something altogether less subtle and more like a bold attack on our senses from time to time. That is not to say there is not anger in the book; there is anger and violence and sadness and loss. But there is also the soft glow of moonlight to cool it, the gentle sound of Mediterranean waves to soothe it, and the sound of café table laughter to partly snuff it out. These are ordinary stories.

IV

It has taken a while to get to this. I have read and I have written. I walked and looked and noticed things and returned to my chair. Sat down, read some more. Wrote again. There have been skeletal thoughts that have fallen away and other thoughts stillborn. Some have been committed to paper, as true to their original spirit as I have been able to make them. And this is what I have come up with.

After encountering the works written about here, it makes me wonder who is making what and for whom. Wonder too whether the thing made is ever anything like the thing received. And whether it matters. Every making of one thing is at the same time the unmaking of another. As much as this has been a looking inward upon the work of others, it is also an opening out of my own.

In many ways the region I have focused on is unlike any I have met with before, on film, on paper. It puts one on guard and makes one tread lightly. The nomenclature sits clumsily in my mouth when I try and use it. The Middle East. The Levant. I feel always like I will ruffle feathers somewhere. There have been so many voices issued, both towards and from here, voices that have always vented such strong opinions. It is hard not to listen to the loudest voice. But issuing a voice of my own in turn is to join the cacophony. Every word spoken seems to beget a deluge more (and still we feel no closer.) There have been so many images, too – spectacles, as Ndebele would have it – that have vied for our attention. Have we not been hardwired to look to these images as though there were no other way of learning?

There have been so many images, too – spectacles, as Ndebele would have it – that have vied for our attention. Have we not been hardwired to look to these images as though there were no other way of learning?

But what I have grown to do – and have been doing for a little while now – is to read differently. To look differently. With a book in my hand, I have learned to let the words linger a little longer. I have drunk in whole scenes on screen and not tried to pick fussily from them, discarding the surplus. I do not throw a scrap away. I know that I am not alone in this. Is not Je Veux Voir a monument to this logic? It is that sense that every single thing holds within it something worth keeping. I am a hoarder. And as I hoard I go beyond the collecting of simple truths – I get a feeling for something. I know now about the Oslo Accords, the Israel-Palestine agreements signed in the mid-nineties in an attempt to broker peace between the two bodies. I know that very complex relationships exist between individuals on either side of the divide. Know about the refugee camps at Rafah, Al-Shati and Jabalia. About the UNIFIL presence in Southern Lebanon. About low-flying Israeli planes stalking the Lebanese borderlands. That the wreckage from the 2006 conflict has been gathered at a site by the coast, broken down by machines into a fine dust and fed to the ocean. But I also know now about the many cinemas that once dotted the old city of Jaffa. That a majdalawi is a robe of hand-woven cloth originating in the village of Al-Majdal. That olives, oranges, almonds, pomegranates and peaches are all grown in Palestinian soil. And I can begin to imagine the fear of a Palestinian camp-dweller who has snuck out at nightfall beyond the guarded boundary of his prison.

Joreige, Hadjithomas, Deneuve, Shehadeh, Mrouré, Saif, Ataallah, Al-Gul – they have both given things to me and to themselves. And me? I too have sifted through the many scraps and have cobbled together a constellation – both for myself and for anyone else who may find something in it. We have all made and unmade things. The most difficult things to understand deserve the most care. And we will never reach a conclusion. The only thing I am clear about in all of this is that nothing should be thrown away. Everything holds something within it worth keeping. Every one thing is tied to another. A single leaf, an apple, a pothole, a hillside, a kidnap, an airstrike.

I am writing this in the garden. The last of the season’s fruit needs to be picked. The sun is up but so is the moon. Its white surface is faint and probably goes unnoticed by many. But for me seeing it conjures up a million fragments in the September sky.

Photo by Jill Granberg