Successive governments have ignored and dismissed complaints of suffering in UK immigration lock-ups. This week, in Parliament and on national television, fresh evidence has been heard.

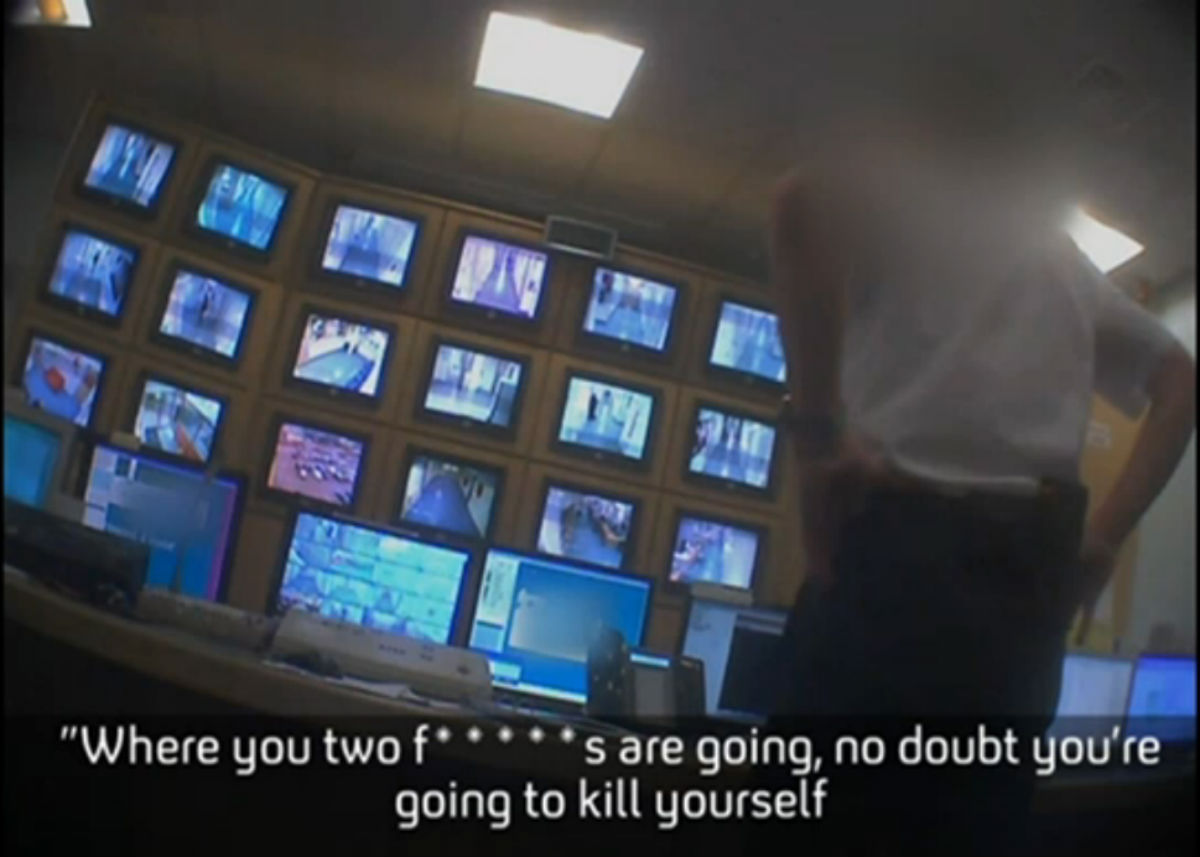

On Monday night Channel 4 News broadcast shocking undercover footage of guards talking about the women in their care at Yarl’s Wood detention centre in Bedfordshire.

“Headbutt the bitch, I’d beat her up,” says one guard at the immigration prison, which is run for the Home Office by the private security company, Serco.

“Let them slash their wrists,” says another.

“I allegedly walked into somebody’s room without knocking,” another Serco man tells his colleagues. “I just like tits. I’m addicted to the viewing of tits.”

On Tuesday a cross-party group of MPs and peers called for radical change in immigration detention in the UK.

The All-Party Parliamentary Group on Migration spent six months investigating conditions on the Home Office’s “detention estate” and they explored other countries’ alternatives to detention.

They found that the UK uses detention “disproportionately and inappropriately”, despite receiving far fewer asylum applications than its European neighbours.

Yarl’s Wood

In their robust and critical report published on Tuesday, the MPs and Peers said that whoever wins the general election in May should impose a statutory 28-day time limit on detention for immigration purposes, introduce automatic bail hearings, and stop detaining women who are victims of rape and torture. (Detention centre rules already forbid the detention of people who have been tortured. Regardless of that, it happens.)

A time limit on detention is only the first step, said the report. “Most problems could be resolved simply by not detaining most of the people currently held under immigration powers,” and the government should work to develop effective community-based alternatives.

Liberal Democrat MP Sarah Teather, who chaired the inquiry, said: “The current system is not working. It’s expensive, ineffective and unjust. We believe the problems that beset our immigration detention estate occur quite simply because we detain far too many people and for far too long.”

She told me that Channel 4’s story echoed what the panel heard during the six-month inquiry: “It is very similar to the type of allegations that people were making to our inquiry in terms of how they experience being detention.”

One woman told the inquiry: “I can tell you, anybody who is [on] suicide watch has sexual harassment in Yarl’s Wood, because those male guards they sit in there watching you at night, sleeping and being naked. You can hear them talking it.”

Another said: “On one occasion I was showering when a particular officer came into the room, using his key and without knocking. I was naked and vulnerable, he apologised but didn’t look away and started a conversation. I shouted at him to get out, which he did in the end.”

Teather and her colleagues heard of one recognised trafficking victim who was detained for more than one year.

Tinkering at the edges

The inquiry report remarked on the wealth of reports over the years documenting evidence of suffering and abuse of process within immigration centres across the UK. The Parliamentarians urged Home Office immigration officials to undertake a full literature review.

Sarah Teather said: “We are not going to solve this problem by merely tinkering at the edges and my worry a bit about these exposés is that sometimes the consequences are just that a few individuals are sacked and that is not going to fix the problem. We are going to need to do a whole scale review of the way in which we work with people.”

She went on:

“There is a culture of mistrust and a culture of misbelief, and a tendency to go heavy on aggressive enforcement techniques rather than engaging with people. That is not actually what other countries do, and it is not very effective. And that kind of culture is what tends to lead to people being treated badly and tends to lead to an experience of extreme anxiety for individuals who are caught up in it.”

The right to liberty

In 2013, more than 30,000 men, women and children were detained in immigration detention centres across the UK, half of them seeking asylum. Many detention centres are former prisons, while larger centres, such as Colnbrook and Harmondsworth, near Heathrow, are built to category B prison standards.

The panel’s key recommendation is a 28-day limit on detention for immigration purposes. Britain is the only country in Europe without a time limit on how long it can detain people subject to immigration controls. European Union rules on immigration and asylum specify that member-states should only detain people in cases where deportation is imminent, with a time limit of 6-12 months given. But the UK has opted out of this directive, and currently detains people for months and sometimes even years. The Home Office’s own guidance says detention should be used sparingly and as a last resort, but evidence presented to the inquiry indicates that people are routinely detained as a matter of course.

Britain is the only country in Europe without a time limit on how long it can detain people subject to immigration controls.

Examining immigration statistics, the inquiry found that the longer a person was detained, the less likely they were to be deported. In many cases people detained for months or years are eventually released. In written evidence to the inquiry, the human rights group Liberty said this was “rendering their detention a human tragedy and a futile violation of the right to liberty”.

Other factors used to make the case for a 28-day limit include: the severe deterioration in peoples mental health after more than one month’s detention, the lack of urgency among Home Office officials in resolving cases and the high cost of detaining people.

Detaining people is more expensive than case-working them in the community, the committee found. The estimated cost of running the entire detention estate in 2013 was £164 million and the cost of detaining one person £32,026. Between 2011 and 2014 the government paid nearly £15 million in unlawful detention cases.

The Swedish example

Teather’s committee defined success as higher compliance, which means more voluntary returns and less litigation, and found this in countries where the system was fair, transparent and dignified. The report notes that in Sweden, people seeking asylum were treated with “dignity”, rather than criminalised.

Migrants and refugees register at regional centres, they are assigned a case-worker and attend regular meetings to discuss and prepare for all possible immigration outcomes. “This assists individuals to feel they are given a fair hearing and are empowered and supported to make their own departure arrangements with dignity.”

Detention really is used in Sweden only as a last resort; in 2013 the average stay in detention was five days. That same year nearly 3,000 people passed through Swedish detention, compared to more than 30,000 in the UK, yet Sweden receives at least twice the number of asylum applications as the UK.

Looks like a prison. . .

Sarah Teather spent a day in a cell at Yarl’s Wood, where around 300 women are held at any one time. “In comparison to the living conditions in the detention centre in Sweden, the cell was bare, shabby, impersonal and the centre noisy,” she said.

“Of particular note were the sanitary towels stuck to the air vents in the walls.” This, she was told, was to block out sounds travelling between the cells, such as other women screaming or the jangling of the guard’s keys.

Yarl’s Wood – undercover in the secretive immigration centre

In written evidence to the inquiry the Church of England said:

“What has been built … is not just prison-like. It looks like a prison: harsh straight lines, built to high-security standards, bare of anything to soften the feel of the interior. It sounds like a prison – large echoing open wings. It feels like a prison: the attempts to call the places where the detainees sleep a ‘room’ is confounded by the fact that they are manifestly cells. The toilets have no seats, just a solid steel bowl. It smells like a prison: that toilet is inside the cell. In many cases, the detainees – who are prisoners, in any normal sense of the word – have to eat in those cells beside the toilet.”

Internet access is arbitrarily restricted. Blocked sites across centres include the BBC, Facebook, Skype, visitors groups’ websites, Bail for Immigration Detainees, Amnesty International, and the parliamentary inquiry’s own website. “The restrictions to sites of groups who offer advice and support to detainees is inexplicable, particularly given the problems many detainees have accessing legal representation and advice inside the centres,” the report said.

The law’s protection

Unlike regular prisoners, people held in immigration detention have patchy access to bail and legal representation, the report found. In 1999, the then government included a clause in the Immigration and Asylum Act allowing for automatic bail hearings within the first eight days of detention, and another before the 38th day.

According to the inquiry this was never enacted. It was repealed in a later immigration law in 2002. Laura Dubinsky of Doughty Street Chambers told the inquiry that whereas in the criminal justice system,

“You’re entitled to legal representation and you’re entitled to disclosure about why you’re being held. Terrorist detention is 48 hours and yet we have this extraordinary situation where immigrants who have such difficulties in obtaining legal representation have barriers of literacy, other vulnerabilities, are expected to instigate their own bail applications before the tribunal and even instigate their own challenges in the high court to the legality of their detention, and that’s an extraordinary state of affairs, and it’s one that’s an anomaly in our own legal system and an anomaly also in the EU.”

One government inspector found that of the people held in immigration for more than six months, nine (16 per cent) had never made a bail application. “This may have been because detainees were unaware of bail processes and/or had poor legal advice,” the report says. “A number of detainees said they did not know how to apply for bail or clearly needed help to navigate the process.”

Some people remained locked up for a more than a year, only because they could not find a bail address.

Witnesses testified to difficulty securing decent legal advice … One witness said after six months, they still hadn’t heard back from their solicitor.

The process of the bail hearing itself is carried out over a video link from the detention centres. In theory, judges are guided to grant bail where there is no reason to detain someone and alternative control measures would suffice. In practice, witnesses told the inquiry, judges often refuse bail in the mistaken belief that removal is imminent: “…they too readily accept statements in the Home Office’s Bail Summary that are not supported by any evidence, and they fail to require the Home Office to show why detention is necessary and that all alternatives have been exhaustively pursued,” said Detention Forum in written evidence. Witnesses testified to difficulty securing decent legal advice. Kay Everett from the Immigration Law Practitioners Association says in many cases people weren’t told about advice surgeries held at detention centres or how to sign up for them. When they did access surgeries, interviews lasted just 30 minutes, not enough time to case-work complex asylum applications. One witness said after six months, they still hadn’t heard back from their solicitor.

“All my friends in here have the same problem as me. We meet the lawyers, they tell us not to worry, and then they never come back or even tell us if they’ve taken our case or not – and for a few months we are hopeful and think they have. They don’t respond to our calls and we lose hope.”

In their final recommendations, the MPs and peers call for the Legal Aid Agency and the Immigration Services Commissioner to carry out regular audits on the quality of advice provided by contracted law firms in detention centres, and that contracts be amended to provide more than 30 minutes per client.

Institutional disbelief

The Parliamentarians were shocked by the evidence they heard about healthcare standards — rudimentary health screening, limited access to medical staff and delays in receiving treatment, including a woman left for three hours after having a miscarriage.

One man described visiting a doctor with four guards and in handcuffs:

“The first time I went there I was handcuffed with my two hands and they used a long chain to … one of my hands. So, all the officers that escorted me to cardiologists, they came into the private room with the consultant. The consultant was very annoyed. He said, look, I cannot treat my client like this. You handcuff him; you want to hear my conversation with him. This is not allowed.

“He said he will not be able to continue with my treatment. So he was talking to them. They have to release one of the hands for him. He asked me to lie down. All the officers. Four officers that took me in to the appointment, they were there. I have to undress in the presence of the officers. He was asking them that two should go out and two should stay in. They refused. They said they were doing their job. So, the consultant asked to discharge me, that he will not be able to continue, because they were interfering into the medical treatment that was given to me.”

The report criticises the Home Office practice of detaining people with mental illnesses. Government inspectors, doctors, nurses, and mental health experts, have warned against detaining people with mental illnesses for immigration purposes. Six high court judgements since 2011 found that the detention of mentally ill people for immigration purposes was a breach of article 3 rights of the European Convention on Human Rights. The Royal College of Psychiatrists gave evidence to the inquiry saying Home Office policy in this area reversed the “presumption against detaining those with mental health conditions”.

Protections in place, such as rule 35 of detention centre guidelines, to protect vulnerable people from being detained, are sometimes ignored, the report says. The panel was shocked that some detention centre staff were unaware that these protections existed. The charity Medical Justice told the inquiry:

“One client who disclosed a history of multiple-perpetrator rape by a violent gang was told her situation did not warrant a Rule 35 report. In the medical notes the doctor concludes: “rape – private. No Rule 35.”… Another client who reported being the victim of an ‘honour crime’ was told to ‘go and google torture’ – presumably a reference to the fact that as the ill treatment did not come at the hands of state actors it did not qualify as torture.”

The panel has called on the government to implement a mandatory training programme for all detention centre staff, which should include dealing with trafficking victims, survivors of rape and torture, and people with mental health needs. It added that pregnant women and women who are victims of rape or torture should not be detained, and gender-specific rules should be implemented in all detention centres.

The tipping point?

Ruth Grove-White, Policy Director at the Migrants Rights Network said: “This report shines a light on the devastating impacts of ‘barbed wire Britain’.

We welcome the cross-party recommendations especially a time limit of 28 days on the length of time anyone can be held in immigration detention. This would have a tremendous impact on the lives of those currently held indefinitely, without any knowledge of when they might be released and at the mercy of the Home Office.”

Dr Juliet Cohen, Head of Doctors at Freedom from Torture and a frequent visitor to immigration detention centres, said: “The report gives an unflinching critique of the UK’s immigration detention system and Freedom from Torture endorses the recommendations made.

“Over the years many credible reports have made constructive suggestions for the improvement of the asylum system, and immigration detention specifically, yet few appear to result in any meaningful action by the Home Office. On this occasion, the desire to create an effective and fair system must trump any other consideration.

On this occasion, the desire to create an effective and fair system must trump any other consideration.

“Of particular concern is the safeguard intended to protect vulnerable people, including torture survivors, from being wrongly routed into detention which has consistently been found to be failing. This inhumane system must be overhauled to ensure that vulnerable and traumatised individuals whose detention is for administrative convenience and no other reason are given the protection they came to the UK to claim.”

Speaking at the report’s launch, the MPs referred to the campaign to end the detention of children as a template for implementation. Work began within a year of the coalition agreeing the policy, they said.

When asked to respond to criticism of how the pledge to end the detention of children has been handled, Sarah Teather said: “I am not claiming that the current system around child detention is absolutely perfect. There are still some children going through the system who shouldn’t be there. However, it is dramatically different. You have gone from a situation of thousands being detained to just a small handful. Sure the system can still be improved and it demonstrates that change can happen.

“At this stage when there is so much negativity and defeatism about change never being possible, I think it is important to hold up an example of where change has been possible. And working together with others we have managed to do that.”

On Wednesday, Channel 4 News released fresh footage, filmed by a detainee on a secret camera at Harmondsworth, and handed to Channel 4 by Corporate Watch.

A Home Office worker, filmed covertly, explains why filming is bad idea: “Say you’re in government, right, and you guys are taking photos of these bad conditions like the rats and whatever other shit that’s in here and you’re sending that outside sending it to the news or whatever — that looks bad for the government, doesn’t it? Or these centre fights or someone’s cutting themselves and you’re taking pictures of that and sending it outside and being like, ‘look what’s happening in here’, they don’t like the bad publicity that would entail.”

He’s not wrong. Sometimes change happens when the light gets in.

This piece was first published by Shine A Light at openDemocracy.