Ben Richardson and Laura Gelhaus investigate food and drink adverts on television. They argue that the food industry occupies a critical position in determining social attitudes toward food and the exclusion of larger people from their adverts should be seriously scrutinised.

Launching its new ‘one brand’ strategy, Coca-Cola’s advert tells you to “choose happiness”. It shows you images of sportspeople, activists, friends and lovers, all of them in celebratory mood. They are different sexes, ages, ethnicities and abilities. It is a panorama of diversity. But none of them look fat. The slender body is dominant.

A series of still shots from Coca-Cola’s advert ‘Choose Happiness: What Are You Waiting For?’.

The advert ends by showing you the different varieties of Coke you can buy; some with lots of sugar in them, some with less. According to the company’s UK marketing director, the campaign is about “motivating people to go further and to take action by choosing happiness”. In plain English, this means encouraging individuals to take responsibility for their own health and wellbeing, with the beneficial side-effect for Coca-Cola of absolving them from blame for the spread of dietary-related disease.

Manufacturers of processed foods have long maintained that their products can be enjoyed safely as part of a balanced diet and active lifestyle, wary of the twin threats of state regulation and consumer rejection should they be perceived as a genuine health risk. As Coca-Cola’s rebrand makes clear, scrutiny on this public relations strategy is increasing as the maelstrom of media reports and political campaigns around obesity and foods high in sugar, fat and salt intensifies.

Most critical commentary on this strategy has focused on the duplicity of the food industry’s ‘personal responsibility’ doctrine, suggesting that voluntary measures like providing more information to consumers about healthy eating were designed to fail. In other words, companies told people to eat a balanced diet knowing full well that this message would be drowned out by the marketing spectacle – the adverts, the offers, the sheer ubiquity of the products – that they would use to push sales.

The widespread criticism is that the food industry produces obesity. But on top of that, it also devalues people with obesity through its public messaging and thereby feeds the wider phenomenon of fat discrimination.

This happens in two ways. First, there is the aesthetic dimension of the food industry’s personal responsibility doctrine. Through press releases, media quotes and infomercials, they constantly reiterate the over-simplified claim that obesity has spread as a result of too many calories and not enough exercise, thereby reinforcing the stereotype that anyone who is obese should be seen as lacking in self-control (the food industry always point out that they are doing their bit to provide healthy options).

For instance, in response to a proposed tax on sugar by the British Medical Association, the UK Food and Drink Federation denied that this would work and repeated the industry mantra that what was needed was “better, more balanced diets and lifestyles” (italics added). Their views were subsequently reported in The Guardian, The Grocer, The Daily Mailand on the BBC, adding ever more grist to the mill of those who believe that what a person eats and how it affects their body is simply a matter of individual choice. In far less measured tones, the CEO of PepsiCo even proclaimed that: “If all consumers exercised, did what they had to do, the problem of obesity wouldn’t exist”. The conclusion we are left to draw from such judgements is that fat people are either making the wrong choices or just outright lazy.

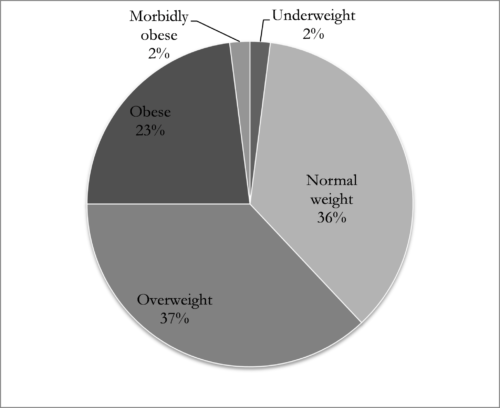

Second, there are subtle but powerful visual messages contained in the food industry’s marketing campaigns. Adverts for the UK’s major retailers and manufacturers of fast foods, soft drinks and confectionery systematically exclude fat bodies. Among the 39 TV campaign adverts on the McDonald’s UK YouTube site for instance, none featured people who looked obese as central characters or restaurant customers. Neither did any of the 35 TV adverts hosted on the Sainsbury’s site. Thus, a social group which account for a quarter of the UK adult population – albeit based on the questionable Body Mass Index method – are, on our interpretation, entirely absent from these and many other adverts (see for yourself in this database of food industry print adverts).

On those occasions where fuller figures were cast on camera, they were typically used for comedic effect. In an advert for Mars’ Snickers as part of the ‘You’re Not You When You’re Hungry’ campaign, one portly actor is mocked for his inability to control his mood and so is temporarily replaced on screen by the famous diva Joan Collins.

Contrary to the prevalence of fuller body shapes in society, companies have (deliberately?) omitted them from their adverts, even those with an evident ‘everyday’ feel as typified by the McDonald’s and Sainsbury’s campaigns. An unintended effect of this is to suggest to the viewer that larger people do not belong in thesocial scenes depicted in adverts; the only exception being when the errant body size is highlighted as such and explained away through humour. As with the personal responsibility doctrine, this lends subtle and tacit support to the belief that fat people are deserving of condemnation, condescension, and social ostracism for having failed to control their size.

UK adult population by Body Mass Index weight classification, 2013*

One riposte might be that the food industry is right to practice fat discrimination, as otherwise it might help normalise obesity and discourage people from losing weight. This is a common sentiment in societies suffering an ‘obesity crisis’ and even the UK’s Department of Health has acquiesced to it, believing it preferable to avoid any written or visual reference to obesity in its Change4Life campaign because many people assigned a derogatory meaning to the term. It is a spurious and dangerous argument. Shame and stigma are widely recognised to be awful motivators for sustained behavioural change and can even be counterproductive, discouraging people from exercising in public for instance.

Such arguments also serve to conflate heavier weight with failing health. Whilst not denying the increased medical risks associated with higher levels of body fat across an entire population, it is misleading to read off an individual’s exposure to things like diabetes and cardiovascular disease from their Body Mass Index without considering a host of other factors including blood pressure, cholesterol levels and insulin resistance. Similarly, while studies show that obese people may be more likely to sustain injuries from falls than people of ‘normal weight’, it would be inaccurate to say that these accidents are symptomatic of weight alone. There is thus an established position in the medical literature which maintains that obesity is not harmful in and of itself, but that ill-health is best ascribed to other factors. What is important to stress here is that it is impossible to deduce a person’s health simply from their size.

What is important to stress here is that it is impossible to deduce a person’s health simply from their size.

What can be harmful is the psychosocial damage wrought by adverse moral judgements about fat people. For instance, perceptions of weight discrimination in places like clothes shops or GPs’ surgeries have been found to strongly correlate with increased symptoms of depression. Young adults interviewed for one piece of research also highlighted the acute discomfort and anxiety they felt in sites of food consumption like restaurants, cafés, and public eating spaces.

Sanctioning discrimination in the name of health is not just ineffective; it also undermines universal claims to human dignity. As argued by legal scholar Lindsay Wiley, this claim was used to overturn the intrusive and coercive interventions initially targeted at people with HIV/AIDS in the US, a rights-based strategy of de-stigmatisation that she posits must now be applied to so-called ‘obesity control law’.

It may not be right, but is the food industry free to practice fat discrimination?

Legally, yes. Representations of size in UK food adverts currently fall between two legal regimes. On the one hand, there is human rights legislation in the form of the 2010 Equality Act which seeks to prevent individuals from discrimination based on certain ‘protected characteristics’ including appearance-based characteristics like age, race, sex and disability. Whether size should also be considered a protected characteristic is hotly debated. In 2012 the All Party Parliamentary Group on Body Image proposed that it should be explored. The Conservative-led government did not take them up on the invitation but did undertake a series of awareness-raising initiatives, including asking the Professional Publishers’ Association to create an award celebrating “the inclusion of diverse body images in magazines”. Given out once, the award has since been scrapped.

More significant are the legal decisions recently reached in the European Court of Justice and a Northern Ireland Industrial Tribunal over workplace disputes, both of which established that differential treatment based on morbid obesity could amount to disability discrimination. This could have far-reaching effects since such discrimination is seemingly rife. For instance, a recent survey of 1,000 UK businesses found that nearly half were less likely to hire obese applicants. In this instance, then, some forms of sizeism would already be covered by the UK’s Equality Act. However, since the Act allows exemptions for legitimate occupational requirements, such as hiring actors to fit a required role, it would be difficult to extend into advertising. More generally, the UK legal system is more open to cases filed by wronged individuals who have been actively discriminated against, rather than class actions brought on behalf of groups structurally marginalised from public life. For the same reasons that people from minority ethnic groups still find themselves under-represented and stereotyped in the British media, it is unlikely that equitable representation of body size in the UK will be best served by appeal to anti-discrimination law.

GlaxoSmithKline had to remove an advert which claimed that the sugar-laden sports drink Lucozade “hydrates and fuels you better than water”

The other legal regime that might be expected to address fat discrimination in food advertising is administered by the UK’s Advertising Standards Authority. Yet here too the question of how bodies are represented is largely ignored, with the issue of discrimination declared outside their remit. Regulation of the food industry by ASA has instead been concerned with its dietary messaging. Nonetheless, it is worth noting that a number of verdicts against food companies have been made for breaches of the rules, indicating their ambivalent position toward the public interest. GlaxoSmithKline had to remove an advert which claimed that the sugar-laden sports drink Lucozade “hydrates and fuels you better than water” while Kellogg’s had to do the same for misleading viewers about the amount of calories in a bowl of its Special K cereal.

Also worth highlighting is the fact that, where other socially-disadvantaged groups have been subject to pejorative portrayal in food adverts, there has at times been a public backlash. In the US PepsiCo was forced by public pressure to remove an advert dubbed “the most racist commercial in history” for playing on stereotypes of young black men as violent criminals, while the global head of beverage company SABMiller has openly criticised his own industry for being “dismissive and insulting” to women in their adverts for beer. Unlike race and gender, however, size relations have not yet been subject to the same sensibility.

Strong legal guidance on the representation of size may be lacking, but the aesthetics of fat are being challenged.

Networks of self-defined ‘fat activists’, many gaining prominence outside traditional media through Internet blogs, have highlighted the personal damage caused by negative body images and advocated instead for greater size acceptance. One example is Dr Charlotte Cooper, who is credited with coining the term ‘headless fatty’ to draw attention to the photos that typically accompany news stories about obesity; another example of the way larger people are (partially) excluded from mainstream media.Responding to this situation, an academic in Australia worked with fat activists there to compile an image library of ‘stocky bodies’ engaging in everyday activities. By having these alternative representations circulate in the media, they intended to disrupt the dominant discourses of obesity by “challenging stereotypes, re-humanising fat bodies and celebrating fat flesh”.

Image SB_IB_food-15 from Stocky Bodies, licensed for research purposes

Other voices have highlighted the parallels between sizeism and more widely recognised prejudices like homophobia, attempting to shift social attitudes against fat shaming. Again in Australia, one commercial devised to promote the idea of Fat Pride tried to do this by comparing cruel jokes about “poofters” and “Jews” to one about “fat chicks”, but was pulled by the television network for being too offensive itself.

Not all strategies of size acceptance have been so confrontational. In London, to some extent mimicking the historic sanctuary offered by the gay bar, “body positive” club nights have been set up to create safe social spaces. Meanwhile, some medical professionals have promoted the idea of Health At Every Size, which seeks to replace an obsession with weight-loss with a focus on health-gain and body respect. The UK group of this global community state that they are not against weight-loss per se, but stress that health improvement can occur independently of weight change and that practices such as mindful eating are a much better way to develop long-term self-care behaviours than shame-induced crash dieting.

These are all facets of the counter-movement against fat discrimination and the public messaging of the food industry should also be part of this debate. In the same way that the fashion industry has a privileged influence on beauty norms, the food industry occupies a critical position in determining social attitudes toward food and its physical embodiment, not to mention an annual UK marketing spend of over £800 million in advancing these ideas. Yet compared with the fashion industry and TV shows like The Biggest Loser and You Are What You Eat, it has so far evaded scrutiny as a cultural force shaping body norms. This should be addressed. Adverts for nutritionally-deficient foods which emphasise that everyone can “choose happiness” except those with fat-looking bodies are ignorant at best, shameful at worst.

* Source of BMI weight classification chart: Adapted from Obesity Statistics (2015) House of Commons Briefing Paper.