In November last year, 100,000 people signed an e-petition calling for an assessment of the impact of changes in the welfare system on sick and disabled people, their families and carers. And 100,000 is a magic number: it triggered a Parliamentary debate on February 27th at the end of which Parliament passed a motion calling on the Government to carry out the assessment demanded.

So far, the government have failed to comply. They argue that ‘the complexity of the modelling required and the amount of detailed information on individuals and families that is required to estimate the interactions of a number of different policy changes’ makes a cumulative analysis impossible.

Is this true? The government regularly makes claims that it can measure things that look pretty complex and uncertain. We’ve been told that, for instance, for every £1 you spend on high speed rail (HS2), you get £2.30 in economic benefit back, which of course requires predicting a whole series of costs and benefits of a future project where construction will not even start until 2017. So are the impacts of austerity measures, particularly on the most vulnerable and disadvantaged, really too complex for the government to measure?

Finding out about the impact of policies on real people

Public authorities already, on a regular basis, measure the impacts of their policies on a range of equality strands including disability, gender, race, religion and belief, sexuality and age. Measurement is carried out primarily through a process known as ‘equality impact assessment’ (EIA). But the Prime Minister is not a fan.

In a speech to the CBI in November 2012 David Cameron said he was ‘calling time’ on equality impact assessments describing them as ‘bureaucratic nonsense’ and ‘tick box stuff’. They were unnecessary because there were enough ‘smart people in Whitehall’ who would think about equality when developing policy.

It’s certainly true that many equality impact assessments have been pretty woeful. It’s also true that many of the most inadequate have been carried out by those same ‘smart people’ in Whitehall. Take the Ministry of Justice’s impact assessment on the effect of cutting legal aid. It acknowledged that women were more likely to receive legal aid than men. But it argued that cutting legal aid didn’t have a disproportionate impact on women because the higher proportion of women who would lose legal aid was in line with the fact that they were more likely to claim it than men in the first place. Now that really does make a mockery of the whole idea of discrimination. It’s like arguing that wounded soldiers would not be disproportionately affected by a decision to stop funding prosthetic limbs, because more of them are getting injured in the first place than your average citizen. It completely fails to engage with why people need services, and what happens to them when they are removed.

The broader problem with the impact assessments undertaken by those smart people in Whitehall is that they stayed in Whitehall when they did them.

Our own research of government EIAs has found that, among other problems, they generally lack any proper consultation with people who will be affected by the measures. As a result, government officials don’t gain any understanding of what the real impact of their policies will be on those affected.

The petition for an impact assessment on changes in the welfare system was asking for something different. It was demanding a cumulative assessment of all the welfare cuts and reforms undertaken by the government on sick and disabled people, their families and carers. This means getting out of Whitehall and finding out about the actual affects of policies on these peoples’ lives.

Undoubtedly there are a great range of cuts and changes currently underway. Disabled people may be affected by cuts to Employment and Support Allowance, Personal Independence Payment, housing benefit, council tax benefit, the bedroom tax, the benefits cap, freeze to child benefits, cuts to tax credits and cuts to spending on health, transport and adult social care. And that does make analysis complex. But when you are experimenting on such an enormous scale with so many fundamental elements of peoples’ lives, you really do have to make every effort to find out what the effects of those policies are. And there are plenty of people outside Whitehall who have worked hard to measure the human impact of austerity and have produced results that politicians should look at carefully.

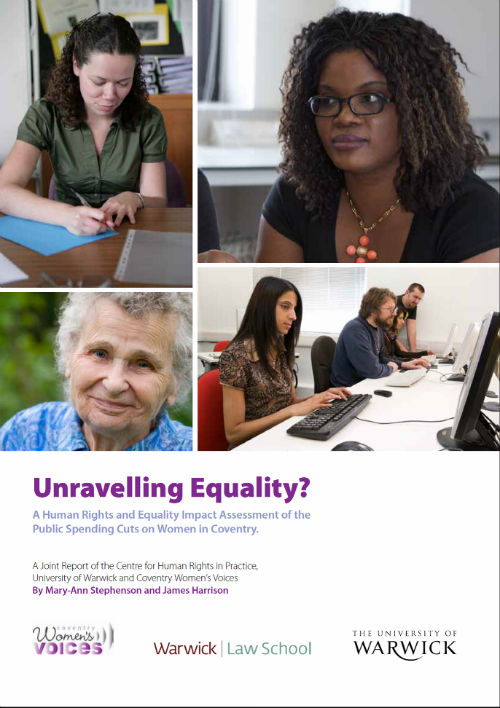

Unravelling Equality Report

In 2011, we produced ‘Unravelling Equality’, the first of three reports examining the cumulative equality and human rights impact of the spending cuts on women in Coventry. Unravelling Equality was the first report of its kind. It examined cuts in housing, education, welfare benefits, employment, health and social care, legal aid, violence against women services and the cuts in the women’s voluntary sector. We used Equality Impact Assessment as a starting point, but added a human rights dimension to it as well. We compared how different groups were faring (the equality dimension) and we examined whether any groups or individuals were suffering particularly badly (the human rights dimension).

Our research found that these cuts will have a significant impact on gender equality. Women will lose more money, more public sector jobs and will be hardest hit by cuts to public services. And the poorest women will be hardest hit of all. The report concluded that we’re in very grave danger of seeing decades of progress made on equality unravelling over the next few years.

Our second and third reports examined the specific impact on older women (‘Getting off Lightly or Feeling the Pinch?’) and BAME women (‘Layers of Inequality?’). All three reports explicitly recognise that not all women are affected equally by the cuts. Disabled women, older women, young women, BAME women, lone parents and women victims and survivors of violence have been particularly badly hit as a result of the intersection between their gender and other factors such as ethnicity or disability (see Kalwinder Sandhu’s article for more on this).

The reports also found that it’s the combination of cuts that are most damaging. Because many women in Coventry weren’t just affected by one cut, they faced a whole series of cuts at once. For instance, when we spoke to older women, particularly carers and disabled women, for our second report, ‘Feeling the Pinch?’ , we discovered that cuts to transport services loomed large in terms of the impact they had on their lives. Their ability to get to work, to education and to get to hospital or other health services was badly affected. Among women over 75, 60% have no access to a car. We already know that 1.4 million people a year don’t access health services because of transport problems. Among the older women we talked to it was very clear that the combination of poverty, transport cuts and cuts to health services were causing major problems.

Getting to hospital to find out your appointment has been cancelled (and we found the cuts mean this has been happening more regularly) can be annoying for anyone. Imagine being on a very low income and finding this out when you’ve already had to pay for a taxi because there’s no suitable bus service; Or you’ve spent a couple of hours taking several buses to get across town. If this happens to you, it can mean that you don’t bother next time.

Many of the women we spoke to were very worried about the reassessment for ‘ring and ride’ services and what that would mean for them – they might be able to get on a bus into town, but have problems getting back with heavy shopping or waiting at the bus stop for long periods in cold weather. If they no longer had access to this service they would go out less – increasing loneliness and isolation, reducing their access to health services, making it harder to buy cheaper food in the supermarket if they’re having to shop locally and increasing costs for heating if they’re at home for longer during the day.

Sometimes the cut can be tiny but the impact significant. At an Asian women’s organisation funded by the local Primary Care Trust, around 40-50 women met every week for discussion on health related issues. They were also able to help each other fill in forms, organise lifts to hospital and people to accompany them to translate. The cost of the group was the hire of the hall and one worker who facilitated the sessions – most of the support was provided by the women themselves. But then their funding was cut. Projects like this help provide resilience to cuts – women are able to help and support each other, when this support disappears the impact of the cuts is far more serious.

Our reports also raise serious concerns about the long term effects on structural inequalities within the UK.

One area where this appeared particularly serious to us, was in relation to violence against women. Estimates of the impact of violence against women vary, but surveys suggest that one in four women experience domestic violence and abuse during their lifetime while one in five experience some form of sexual violence.

In Unravelling Equality, we showed how women victims and survivors of violence in Coventry were likely to be affected by cuts to the budgets of the police, Crown Prosecution Service and health services, combined with cuts to voluntary support services, welfare benefits and legal aid. Together these cuts risked a situation where there would be less successful investigation and prosecution of offenders, more ongoing mental and physical and sexual problems for women, and more women trapped in violent relationships. This example shows how you cannot simply add up the impact of different cuts. You need to examine the way the different cuts interact. A series of smaller cuts by a range of different organisations might add up to a ‘perfect storm’ which threatens our ability to tackle serious human rights issues.

Ann Lucas, Chair of Coventry City Council speaks at the report launch

In Coventry, the City Council has made a commitment to continue to fund violence against women services, meaning that the situation is not as bad as in other parts of the country. But nationally a snap shot survey by Women’s Aid in 2013 showed that in one day 155 women and 103 children were turned away from refuges because of lack of space.

By focusing on the lives of groups and individuals affected by a range of cuts, it is possible to uncover some really profound (and very disturbing) impacts. Our reports demonstrate that ‘measuring’ the impact of public spending cuts is not only possible, it’s an absolute necessity. Without an understanding of the combined impact of a series of different cuts (as in the case of violence against women) policymakers can proceed in their silos blissfully unaware of how the cuts combine with others taken elsewhere to have devastating overall effects. There are so many cuts happening at once it can be difficult for people to keep on top of everything. Even in the relatively small area of Coventry, we found that both councillors and public officials who knew a great deal about cuts in one area didn’t know what other cuts would also be affecting the same groups of people.

Building up the National Picture by Investigating Locally

The work we did in Coventry examined what was happening locally. Often we were asked the question – why are you looking at the local situation, when the key decisions are being made nationally?

Local government and other public bodies in the Coventry area sometimes felt that we were being unfairly critical of their decision-making, when their own resources were constantly being cut by the national government. And we had a huge amount of sympathy for the incredibly tough decisions that they had to make because of funding cuts imposed from above.

But we concentrated on our local area because we knew that the combined impacts we were assessing would have a different effect in different areas of the country for a number of reasons. For instance, although cuts to welfare benefits have taken place across the UK, some of these cuts, like cuts to housing benefit, will vary dramatically in their impact depending on local rents and availability of rented accommodation in both the private and social sector locally. Decisions about cuts to services are being made at a local level by individual local authorities, police authorities, clinical commissioning groups etc. So to understand what the impact is of public spending cuts on the lives of individuals, you need to understand what is happening locally.

Fortunately, there’s now evidence of the impacts of public spending cuts being gathered by groups up and down the country. Our reports in Coventry have been followed by a series of reports in other parts of the country including Newcastle, Birmingham, Manchester, London, Bristol, Wakefield, Hampshire and the East Midlands as well as a number of reports looking at impacts in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

And there’s also increasing amounts of guidance and support for those who want to undertake their own assessments; for public authorities as well as voluntary organisations. In Scotland, we worked with the Scottish Human Rights Commission and the Equality and Human Rights Commission to produce a set of good practice building blocks for public authorities who want to undertake Equality and Human Rights Impact Assessments. Those building blocks were tested by Fife and Renfrewshire Councils. The results of the pilots were launched in April this year. We also worked with the TUC to produce a toolkit for trade unions and women’s groups wanting to undertake studies, which was used by Fawcett groups in Bristol and East London.

In fact, there are now so many reports and assessments that we decided to set up a database of assessments at our Centre so we could keep track of them all. They have sought to uncover and highlight the human cost of public spending cuts either through statistical analysis of the groups most likely to be affected, assessments of the actual (or likely) impact on those groups and individuals, or a combination of the two. If you combine the local reports and assessments with those that have looked at the overall national picture, we now have more than 150 reports and assessments in our database.

All of this suggests that measuring the human impact of austerity is not only possible and vitally important, but that it is already happening up and down the country.

It’s happening because individuals and groups from all kinds of backgrounds and perspectives believe they can and should find out what’s really happening as a result of the complex web of public spending cuts that are currently affecting peoples’ lives.

The national government should be embracing these efforts, and utilising this wealth of research to help it make better decisions; to take action to reduce and mitigate the effects of cuts on those least able to cope; and to ensure that the existing structural inequalities in our society are not further entrenched because the cuts disproportionately affect services that are vital to particular groups (like services for women who are survivors of domestic and sexual violence).

But in the absence of action by central government, this research is also a vital tool for all those concerned about the increasing inequalities of our society that will be exacerbated by the public spending cuts. Research into the real impacts of austerity on real peoples’ lives is vital to re-frame the debate away from a simplistic narrative about strivers and scroungers to one that recognises the complexity of why we end up as a ‘have’ or a ‘have not’. And when more and more local authorities and academic institutions join civil society actors in undertaking such research and publicising the findings, it becomes harder and harder for central government to put its fingers in its ears and claim that such measuring efforts are impossible. It also becomes harder and harder for them not to take action to tackle the impacts.

Photo by Barbara Krawcowicz