In his 2011 book ‘The Precariat’ Guy Standing argued that the insecure employment and irregular work being normalised within capitalist economies was creating a whole new social class. To investigate this further, Ben Richardson looks at how precarity affects people’s diets differently to poverty, and asks whether the precariat could mobilise politically around the issues of health and hunger.

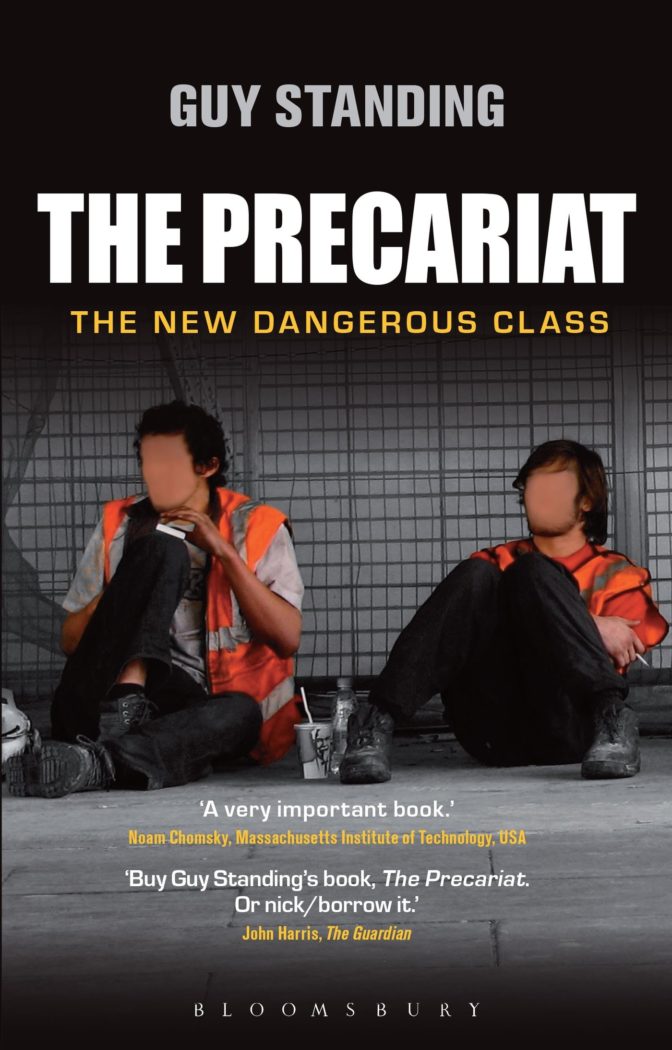

The construction workers on the front cover of Guy Standing’s book The Precariat are faceless. But there is one small visage smiling out at the reader. It’s Colonel Sanders. The workers are on a break and a KFC takeaway is their meal of choice.

Standing argued in the book that within mature capitalist economies like the UK, a new social class is emerging. Working in precarious jobs without clear career paths, these people were seemingly distinct from the old proletariat that at least had lifelong occupations. They were thus dubbed ‘the precariat’. This thesis has been controversial. Some academics responded by saying that the precariat is really just a segment of the larger working class. Others said that precarious employment is best understood as a process affecting the entire labour hierarchy. As proposed by Matt Davies, one way of exploring whether a new social class, with its own sense of identity and ways of behaving, is emerging is to look at the pathologies of precarity. Taking the provocative association of Standing’s cover as a starting point, this article asks whether the hunger and dietary-related disease connected to precarious work is giving this group of people a specific class consciousness.

In its flagship study on the burden of disease, Public Health England concluded that unhealthy diets, meaning those that are nutritionally imbalanced, are now the biggest risk factor for disability and premature death in the country, ahead of tobacco smoke, high body mass index and high blood pressure*. By analysing national statistics from the family food dataset, we can see how some jobs are associated with riskier diets than others.

The two occupations in this survey which give us the best proxy for ‘the precariat’ and ‘the salariat’ (another one of Standing’s classes) are routine occupations and higher professional occupations**. According to the Office for National Statistics which oversees these categories, the former typifies the ‘labour contract’ of piece work payment while the latter typifies the ‘service relationship’ of salaried work with long-term benefits.

Importantly, these patterns of consumption are not simply a function of income.

Over the period 2012-14 those in routine occupations spent on average £32 per week on food and drink, compared to £51 per week by higher professionals. What is more significant is that these budgets were spent on different products. Breaking down the expenditure on food purchased for household consumption we find that people in routine occupations spent proportionately more than higher professionals on processed meat, cakes, bread and potatoes, and absolutely more on soft drinks and chips/crisps. They spent proportionately less on fresh fruit and vegetables, fish, and alcoholic drinks.

Dietary difference between ‘salariat’ in higher professional occupations and ‘precariat’ in routine

| Product category | Higher professional occupation (pence per person per week) | Routine occupation (pence per person per week) | Routine occupation as % of higher professional | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top five product categories where people in routine occupations spend proportionately more than those in higher professional occupations | Processed potatoes | 78 | 94 | 121 |

| Soft drinks | 89 | 105 | 119 | |

| Fresh potatoes | 36 | 35 | 99 | |

| Bread | 123 | 118 | 95 | |

| Cakes, buns and pastries | 67 | 61 | 91 | |

| Top five product categories where people in routine occupations spend proportionately less than those in higher professional occupations | Alcoholic drinks | 395 | 231 | 58 |

| Fish | 152 | 81 | 54 | |

| Other fresh vegetables | 151 | 81 | 54 | |

| Fresh and processed fruit | 304 | 151 | 50 | |

| Fresh green vegetables | 66 | 30 | 45 |

Source: Author’s own derived from data to spending on products for household consumption in Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (no date) Family Food Survey dataset for 2015. Available from Family Food Datasets.

In nutritional terms, this translates into a ‘precariat diet’ that is lower in total protein and vitamins and minerals, and higher in sugar and total calories, excluding alcohol, than its salariat equivalent***. Those in routine occupations consume 2,044 calories per day and those in higher professional occupations 1,818 calories per day. (The possibility that the salariat has its own dietary pathology, namely hazardous drinking, is cause for separate enquiry.)

Importantly, these patterns of consumption are not simply a function of income. In other words, Precarity shapes diets in different ways to poverty. Comparing the data against the purchasing habits of heads of households in the lowest decile of ‘equivalised income’ – that is, income after tax and accounting for family size – we find that those in the poorest households actually spent 29p more per week on fresh and processed fruit, fish, and fresh vegetables than those in routine occupations. They also spent £1.23 less per week on processed potatoes, soft drinks, bread, cakes and meat products.

The class characteristics that Standing attributes to precarity give some clues as to why such dietary differences might exist.

First, the precariat have distinctive relations of production, or labour relations. Standing argues that increasing numbers of people, and in particular young adults, have become used to continually changing jobs and employers. They are formally over-qualified for the roles they take but unable to build a career and develop an occupational identity. This flexibilised workforce is also one which has little control over how it spends its time. Zero hours contracts, short-term employment, shift work, long commutes, and the variety of tasks associated with finding and restarting employment (what Standing calls ‘work-for-labour’) can all destabilise established patterns of daily life****. This in turn makes planning regular meals difficult, disrupts social lives, and encourages irregular eating. This idea resonates with research which finds that snack time – and not breakfast, lunch, or dinner time – is the most frequent occasion when Britons eat. The dietary impact is due to the fact that these changing ways of eating privilege industrially-manufactured ‘ultra-processed’ foods that can be readily served around the clock. They also permit uninhibited eating, where dietary norms around portion sizes and meal composition are more easily ignored, because people are either dining alone or outside conventional times/places.

A second defining feature of the precariat is its distinctive relations of distribution, or sources of income. For the precariat this is almost exclusively money wages. They are bereft of the non-wage benefits extended to the salariat such as generous pension entitlements, medical coverage and subsidised food at work. Where other forms of social protection, including state benefits or community safety nets are absent too, the precariat are left exposed to any shortfall in paid hours. When such hardship bites, it is often via food consumption where savings are found. Recent surveys aimed at struggling families by Save the Children and Netmums both found that around one in five parents had skipped meals to help cut back on household spending. Other responses include trading down to low-cost alternatives, and switching from fresh food to processed food – both of which occurred during the post-recession period in the UK, and as shown by the Institute of Fiscal Studies, adversely affected nutritional intake too.

This income vulnerability relates to the third feature of the precariat: its relations to the state. According to Standing ‘the precariat is the first mass class in history that has systematically been losing rights built up for citizens’. This has rendered them more like denizens of a country than citizens of it, subject to the conditions typically faced by migrant workers such as restricted economic rights and limited legal recourse. Related to diet, this resonates most clearly with the turn to foodbanks. The systematic erosion and individual sanctioning (often incorrectly) of entitlements to unemployment and housing benefits have been identified as a leading cause of foodbank referral. Again, it is important to stress that this doesn’t affect only the very poorest in society. Research on foodbank users in northeast Scotland identified that sudden and unanticipated loss of income was the main factor for referrals, but found that only 12% of these people came from the lowest category of the ‘Scottish index of multiple deprivation’. The handout diet is hardly a healthy one. Not only does the lack of fresh produce means foodbank parcels tend to be deficient in fibre, calcium, iron and vitamins, but the shame associated with visiting foodbanks also raises concerns about people’s mental wellbeing, reminding us that healthy diets encompass more than just nutrients.

Who are the precariat? Standing identifies a variety of groups making up its composition, but one of the most notable is the large number of women that have entered the workforce over the last three decades. Not only have women provided a ‘reserve labour army’ for companies to draw on, but their employment has also enabled certain job roles to be feminised as flexible and low-skill in keeping with the historic treatment of female domestic work. In thinking about how people are fed, the changing working life of women is more important still. The proportion of working-age women in the UK labour market has increased from 54% in 1984 to 70% in 2015. Yet as shown by the last time-use survey carried out by the Office for National Statistics in 2005, women still retained primary responsibility for feeding the family. Even when doing the same duration of paid work as men, women still spent an additional half an hour a day on chores, with cooking and washing-up accounting for most of this housework. The time constraints brought by this double burden go some way to explaining the declining amount of time dedicated to meal preparation in British households and the high proportion of calories in such meals derived from time-saving ultra-processed food.

Politically, there have been three different responses to these pathologies of precarity. One has been to argue for better industrial food.

This is perhaps an uncomfortable ideological position for those on the Left to adopt, since it seems to concede too much authority to corporations and their organisation of food provisioning around the profit-motive. Nevertheless, the consumerist call for culinary modernism opens important space to consider how cheap, quick and healthy meals could be sold at scale. This perspective also takes issue with the potentially oppressive discourse of dietary rectitude that valorises home-cooking and casts convenience food as tasteless – a claim which can (and does) easily slip from culinary judgement to cultural denigration.

Another response has been to agitate for better jobs. This has involved attempts to reconfigure the working day to allow meaningful time to eat and recover, with strategies ranging from micro-resistance in the workplace (insisting on taking a full lunch hour, for example) to union strikes over inadequate breaks. Also within this category are efforts to improve the stability and level of wages, especially for those working within the food industry. It is worth noting here that the lowest paid jobs in the UK include bar workers, waiters and waitresses, kitchen and catering assistants, and cashiers – all earning less than £300 for a full week’s work. Zero hours contracts are also most prevalent in the ‘accommodation and food’ industry. An estimated 199,000 jobs fell into this category in 2016.

The ‘slow food-slow time’ analogy can arguably be flipped over.

Actions against inadequate pay and conditions in the food industry include the organisation of ‘independent contractors’ working for Deliveroo and UberEats, protests online against the use of unpaid ‘work experience’ labour in Pret A Manger, complaints about the deductions from staff tips by Las Iguanas, pressure on McDonald’s to allow its staff to choose fixed-hours instead of zero-hours contracts and boycotts of Byron Burger for its duplicitous role in a Home Office raid on illegally employed staff. These can all be seen as attempts to push back against a creeping precarity affecting both native and migrant workers, recognising that 40% of the food manufacturing workforce and 28% of the food and beverage service workforce are foreign-born. The constitution of the precariat has been a transnational phenomenon.

A final response has been to reclaim leisure time. In part this has concerned a reallocation of the unpaid work of food provisioning. This can happen within the household via intra-family negotiations (over who does the daily drudgery of washing the pots, for example) or between the household and the state (as seen in the growth of school breakfast clubs). But it has also involved drawing boundaries around the necessity of paid work, in effect delimiting labour. The debate on the UK government’s attempt to extend Sunday trading hours can be seen in this light, where the sanctity of a Sunday evening for people to dine together and prepare for the week ahead was ultimately preserved. Some of the proposals in Standing’s ‘politics of paradise’ also fall into this camp. He calls for a replacement of ‘workfare’ social security that forces people to look for jobs or face sanctions with a universal basic income instead, paid regardless of employment status. The spirit of this proposal is to allow people to live first and labour second. Indeed, taking inspiration from the slow food movement, Standing argues that such policies could contribute to a ‘slow time movement’, one in which communal activities and localised cultures can be properly nurtured, free from the unceasing demands of paid work.

The ‘slow food-slow time’ analogy can arguably be flipped over. The harried schedules of working life within late capitalism have become symbiotic with buying fast-food and eating food fast. But will this dietary pathology contribute to a class conscious precariat? Two pathways seem open. If the focus is on agitating for better jobs, then this will highlight the hand to mouth existence particular to those in precarious employment positions. This makes it more likely that the precariat will turn into a ‘class-for-itself’, pursuing strategies in its own interests and becoming antagonistic to other social classes. If the focus is instead on demanding better industrial food and fighting for less work, then these are issues that have cross-class appeal that could subsume the concerns with precarity within a broader social protection agenda.

Acknowledgements

This writing emerged out of a walking tour on food and politics organised by Tomáš Uhnák for the Delfina Foundation in which the author participated.

*Specifically a diet which is: (a) low in fruit, vegetables, whole-grains, milk, nuts and seeds, calcium, seafood omega-3 fatty acids and polyunsaturated fatty acids; and (b) high in red meat, processed meat, sugar-sweetened beverages, trans fats, and sodium. See Public Health England (2016) ‘Changes in health in England, with analysis by English regions and areas of deprivation, 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013’, The Lancet, 386, pp. 2257-2274.

**Standing’s class structure comprises plutocrats, elite, salariat, proficians, core (traditional proletariat), precariat, and the lumpen underclass.

***The nutritional data refers to food eaten inside the house and outside the house.

****Over 2% of the UK workforce are on zero-hours contracts and 17% are asked to do shifts. The average commute time is estimated at almost two hours a day. See respectively Office for National Statistics (2016) Labour Force Survey: Zero Hours Summary Data Tables; Trade Union Congress (2013) ‘Working Time’ excerpt from Hazards at Work: Organising for Safe and Healthy Workplaces; Royal Society for Public Health (2016) Health in a Hurry. London: RSPH.

Banner photo by Jabiz Raisdana.