The Annual United Nations Forum on Business and Human Rights is the world’s largest gathering dedicated to discussing companies and their human rights impacts. In its fifth year, the forum last week attracted more than 2,500 participants from business, government, civil society, UN bodies, trade unions and academia. James Harrison attended the forum and reports for Lacuna. He reflects on the human rights challenges posed by global business activity, which appear even greater after recent Brexit and US election results. He finds inspiration in the work of dedicated individuals fighting bravely and creatively for change, but leaves the Forum concerned about the role being played by the United Nations.

The Challenges

The 5th UN Forum on Business and Human Rights takes place at the Palais Des Nations, the UN’s headquarters, in Geneva. I approach the Palais on the bus from Geneva railway station. Flags of UN member states form a guard of honour leading up to the Palais’s imposing golden-stone façade.

Swinging round the side of the Palais, we arrive at the Pregny Gate where long queues of attendees are slowly navigating the UN’s complex security process. By the time I have been given a name badge and my bags have been scanned, the opening plenary of the Forum is about to start. I rush across the Palais’ grounds, into a large atrium where security guards initially bar entry into Room XX. It’s full I am told. I manage to find another entrance and make it inside. Looking round the vast hall as I enter, coloured stalactites on the ceiling add to the cavernous feeling of the place. The only spare seats are those reserved for the media. No one seems to be taking these, so I sit down as the session starts.

Room XX, Palais des Nations. Ceiling by Miquel Barceló. Photo by BriYYZ via Flickr

Jeremy Oppenheim, Programme Director of the Global Business and Sustainable Development Commission reminds the audience early on of the scale of the human rights problems embedded within our global systems of production.

“There are still over 160 million children who are working at ages where they should not be working. Half of them are working in hazardous conditions. There are between 20 and 40 million people in forced labour, modern forms of slavery… There are well over 600 million people in [global] supply chains who are being paid significantly less than a living wage.”

Mr. Oppenheim suspects that every person present in Room XX will be wearing a piece of clothing, or carrying a phone that is, at least in part, made by people whose fundamental rights have not been respected

Mr. Oppenheim suspects that every person present in Room XX will be wearing a piece of clothing, or carrying a phone that is, at least in part, made by people whose fundamental rights have not been respected. Even in a room of human rights proponents, we are all complicit.

Over the next 3 days, more than 60 workshops take place in a variety of rooms around the Palais. Most sessions are full to bursting. Diverse panels delve into specific human rights problems. Many examine the exploitation of workers, from tea plantation workers in India to child workers mining cobalt in the Demoratic Republic of Congo. Other panels explore human rights problems for the communities in which businesses operate, from open cast mining in Mexico, to rubber plantations in the Mekong.

A number of sessions highlight the grave dangers facing those trying to protect communities from these abuses. At a plenary session in the UN Assembly Hall, Gillian Caldwell from Global Witness tells us that 2015 was the deadliest year ever for human rights defenders. As Global Witness has reported. “More than three people were killed a week in 2015 defending their land, forests and rivers against destructive industries”

The most authoritative voice at the Forum is Professor John Ruggie. He is the author of the UN’s Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), which are very much the centre-piece of the UN’s efforts in this field. In his first words he raises a different set of problems and challenges: “I suspect, like me, you were surprised by the results of the US election and Brexit” he says. Suddenly, among people who have up until now listened quietly, there are murmurings and mutterings all around me, as if people are still in the process of coming to terms with these events.

Brexit and the US elections are discussed throughout the Forum, and Ruggie himself concludes his speech with a warning:

“[There is a] growing threat that globalisation faces from populist nationalism in industrialised countries….These populist forces involve people who have been left behind by the liberalisation and technological innovations that have made it possible to slice and dice production processes into the most minute of parts, each located where labour costs are cheapest or the regulatory context is the most malleable. Surely a level playing field is a better answer to these challenges than more Brexits or other such electoral surprises?”

But how can we create that level playing field? Linda Kromjong, Secretary-General of the International Organisation of Employers reminds us about the contribution that global supply chains have made to record numbers of people lifted out of poverty, particularly in China. No one at the Forum is suggesting that supply chains should be cut, that production should be returned to industrialised countries at the expense of poor workers and communities in the developing world. Instead, everyone is focused on how supply chains can become more responsible, how workers and communities everywhere can be better protected.

The Hope

The sheer scale and global reach of the Forum is incredible. I hear presentations from individuals who come from more than 30 different countries over the course of three days. Most speak fluent English. But translators sit in booths, tucked out of sight, translating Spanish, French, Portuguese, Russian, Arabic and a host of other languages into English, allowing myself and others to gain the perspectives from grassroots activists and a range of practitioners from all over the world.

I hear from two particular types of people who give me hope at the Forum. First there are those who are seeking to uncover human rights violations. For instance, I hear cobalt mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo discussed at several sessions I attend. These discussion are possible because of the intrepid activists and brave journalists who uncovered the story of the terrible conditions of mine workers in Democratic Republic of the Congo, and then pieced together the journey taken by cobalt into mobile telephones all over the world.

This work is vital in creating business responsibility for human rights abuses

Reading the reports and articles by these journalists and activists in the breaks between sessions is a reminder of the dangers and difficulties of first finding human violations and then tracing responsibility all the way through complex global supply chains. This work is vital in creating business responsibility for human rights abuses.

The second group of people who give me hope are those who are using the ‘leverage’ of powerful organisations to make change happen. And it is in two sessions early on during the last morning of the forum that I am most inspired. The first session starts with Katherine Schwenn, from the City of Madison in Wisconsin USA, explaining how her city is now making efforts to ensure that all uniforms the city purchases for its police, fire brigade and other public offices are produced by workers paid a living wage and whose basic labour standards are protected. Pauline Gothberg talks about similar efforts on a much wider range of products by County Councils and Regions in Sweden. Trinidad Inostroza tells us how, in Chile, more than 200 companies have been blacklisted from doing business with the state because of not respecting fundamental labour rights.

“Public procurement amounts to around 12-13% of GDP in the EU and US. If we use the combined leverage of public procurement, then we can do amazing things.” says Björn Claeson, Director of Electronics Watch. He and his fellow panelists explain some of the complexity and difficulty involved; getting public authorities on board, agreeing contracts that ensure responsibilities are passed down throughout the supply chain, and then creating robust and sustainable systems for checking that workers’ rights are in reality respected.

Small pockets of transparency, small pockets of leverage, which seem to be leading to real change in global supply chains. But we need to do so much more. As Professor Ruggie argues:

“More than 1 in 6 workers today are part of multinational value chains. Also reflect on the fact that many of these workers … have families. They live in communities who suffer the ill effects and reap the benefits of how those workers are treated… A concerted effort by business to respect the human rights of workers … and the communities around them would have [significant] transformative effects.”

There are many companies at the forum who talk about their extensive efforts to make sure their supply chains respect human rights; from Apple to Coca Cola, from Nestlé to BP. But listening to their speeches it is impossible to know whom to trust. I have no way of judging whose efforts are extensive, genuine, transformative. Whose are limited, questionable, aimed only at preserving and enhancing the company’s brand.

The Questions

Can the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), the cornerstone for all action on human rights and business at the international level, help ensure that companies take their human rights obligations seriously? The forum is, in part, a celebration of the UNGPs’ fifth anniversary. But I leave as puzzled as when I arrived about the UNGPs’ actual impact on real world human rights problems in global supply chains.

There is one aspect of the UNGPs that I know about more than any other. I have myself researched extensively on the biggest responsibility which the UNGPs place on businesses; that they should conduct human rights due diligence (HRDD) of their business operations. At every session I attend, companies, states and UN actors mention HRDD. But nowhere is practice discussed in any detail. What I find at the forum, is exactly what I have found when looking at corporate websites. No company is willing to share their methodology for undertaking human rights due diligence, or their detailed findings.

And so outsiders like me are left to wonder what is going on behind closed doors and to worry whether the UN may be facilitating ‘superficial legitimation’ of corporate human rights performance, rather than deeper knowledge and understanding of what is actually happening in global supply chains.

In a break between sessions, I meet with Kendyl Salcito in a café with glorious views out over Lake Geneva and the mountains beyond. Kendyl is co-founder of Nomogaia. I have long admired Nomogaia as the only organisation globally who have published detailed HRDD methodologies and robust reports on the human rights performance of companies including mining operations, tree and fruit plantations and pipeline projects. I ask Kendyl why she isn’t speaking at the forum.

“I have never been asked. And I am not sure that anyone really wants to discuss the kind of complex processes we undertake. It seems to be beyond what the UN wants to support.”

At every session of the Forum, the UNGPs are continuously namechecked, but their actual impacts are never discussed. At the session on public procurement, I ask the panellists directly how the UNGPs will help future efforts to create more ethical procurement processes. No one seems sure how to answer. HRDD may be useful, but it’s not entirely clear how.

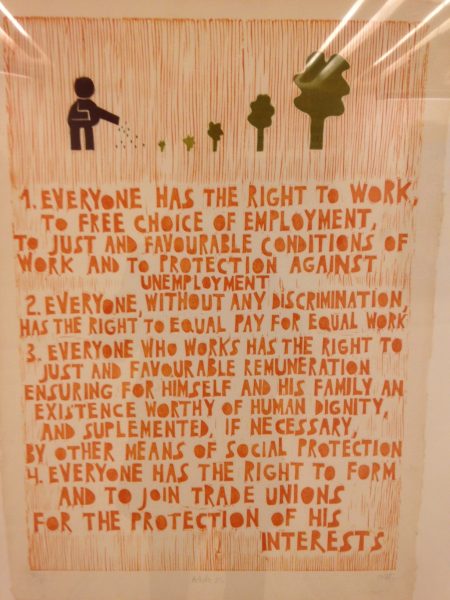

Picture in the atrium of the Palais des Nations

At another session, it is governmental representatives who talk about their engagement with the UNGPs. Representatives from Colombia, Kenya, South Korea, Mexico, Mozambique, Italy, France, Norway, Japan, Finland, Poland, the United Kingdom, the United States, Greece, Switzerland, Slovenia and Chile one by one describe their efforts to create a National Action Plan on business and human rights. The audience gets restless, considerable numbers leave. But I stay. I feel hypnotised by the seemingly endless repetition of bureaucratic processes. It is only towards the end that Fernanda Hopenhaym, speaking on behalf of civil society, breaks the monotony: “It’s not about how many action plans we have globally, it’s also about their quality.”

And so leaving the Forum, I wander through the atrium again, this time at a more leisurely pace, looking at the walls where the human rights which are enshrined in UN Treaties are colourfully depicted. But my mind is no longer filled with hope and inspiration from encounters with cobalt activists and procurement practitioners. Instead I am worried that the UN may be prioritising the engagement of states and corporations over efforts to hold them to account, to ensure that they do something meaningful.

Read James’ follow-up blog post: ‘Business and Human Rights: What should the UN be doing’