Morocco’s cities have one of the highest rates of youth unemployment in the world, with young people struggling to find affordable housing and meet basic needs. In this story, our author spends 24 hours with a group of Moroccan youngsters in Casablanca, hearing how they handle these pressures while looking on the bright side of life, just as the Arabic exclamation “Raha!” suggests.

I am sitting out on the terrace of a beach shack in Casablanca, soaking up the afternoon sun, my hat slightly tilted so I can peer at the last of the golden light setting over the Atlantic Ocean. The café is one of many along the Corniche — a beautiful seaside promenade lined with palm trees along panoramic views of the coastline. The Hassan II mosque — a vestige of Moorish splendour — stands proudly against a dramatic ocean backdrop, undeterred by the waves crashing against its façade.

At the adjacent table, a group of animated boys raucously chit-chat away as they delight in artificially-flavoured, brightly-coloured ice cream purchased for less than a couple of cents. One captures my attention. I notice the shoddy stitch work on his pair of knock-off ‘Abibas’ sneakers. The worn-out jersey emblazoned ‘Wydad AC’ — a Moroccan soccer club popular amongst poor kids in a country where sports not only unite but also provide an outlet to day-to-day ennui. He has his feet propped up on the table, imperturbable and nonchalant, almost in defiance of social conventions. He smirks sardonically, as he scrutinises the overly pompous crowd in the more ‘high-end’ terrace restaurant next door, almost amused at how anyone could take themselves so seriously.

‘A Casawi [local from Casablanca]’, I deduct from the inflexions in his dialect. Though his unfazed attitude, and how unimpressed by the surrounding opulence, tells me he must hail from a nearby shanty town on the outskirts. I follow his gaze as he pauses from devouring his now-melting Solero sorbet to contemplate the glorious sunset vistas. He scans the bed of sea urchin spines covering the honey-coloured sand. The flock of pelicans in the distance skimming over the water. Then the blue-shuttered homes lining the horizon, before lingering on the tiny barbecue stalls overlooking the ocean where a carousel of fishermen come-and-go carrying nets of gleaming fish. Soon after dawn, locals will be feasting on succulent red mullet for a few dirhams. His mouth trembles at the aroma of frying fish.

He inhales, and as if his heart and soul have just suddenly been permeated with all the joy and gratitude in the world, he exclaims: “Raha!”

Chances are, if you’ve been to Morocco, you’ve heard locals use the word “Raha” colloquially. In its simplest form, the Arabic meaning for Raha translates to “Happiness, Freedom, Bliss”. It slips out of the mouth in instances of intense rapture — beatitude, ecstasy — and captures the essence of Moroccan culture. A testament to the inexorable naïveté with which we delight in the littlest things. An ode to the veracious way we rejoice in moments of exquisite joy and ravishing beauty, that we know are temporary. An invitation to let oneself be wholly swathed in the present.

I stare at him a bit longer. The human allegory for all of Morocco’s forgotten lot. Homeless youth. School drop-outs. Parking boys. Street vendors. Rag-pickers and shoe-shine boys. Cataclysmic levels of despair and misery — softened by youthful roguishness, riotous cheekiness, buoyant modesty and pathological generosity all at once.

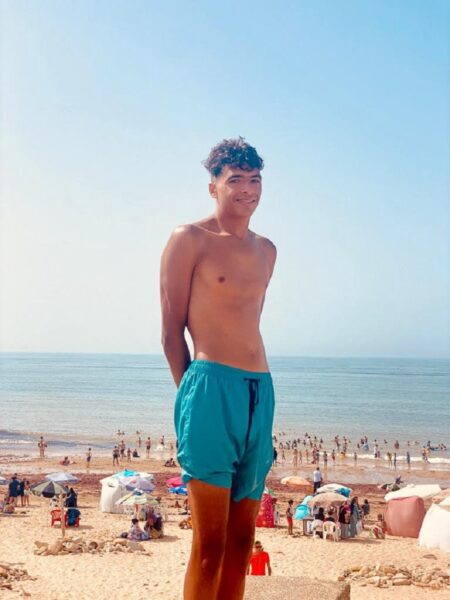

The beautiful boys of the Corniche — how do they do it? I follow the boy — Hussein — out of the café and ask if I can tag along the next day. Perhaps shoot some portraits.

Hussein, staring cheekily at the camera. The Corniche, packed, can be seen behind him.

8 am-10 am. I am standing at the meeting point Hussein advised, near the railing overlooking the sea where fishermen have started lining up. It’s a scorching hot Sunday morning. The beach has already opened for lovers’ trysts — a grey-haired couple bikes past us, while a few young paramours have sought refuge under the shady grove, perhaps hoping to escape the watchful eyes of parents. A man is selling candy from an old wooden cart a few meters away; the scent of warm candy floss tickles my senses when I am interrupted by the joyful Hussein. He lets out a sigh of relief, “I am glad I have a reason to leave the house today!”

North Africa has one of the highest rates of youth unemployment rates in the world. With six out of 10 Moroccan youth unemployed or between jobs*, the Corniche provides solace away from the hectic, congested bustle of the medina — a vulgarised term loosely used to refer to poorer neighbourhoods. At home, 23-year-old Hussein explains he spends most days cramped in the one-bedroom unit he shares with his parents and two younger siblings. Exorbitant gas prices also make it increasingly difficult to travel, “I only use my motorbike in case of extreme necessity”. Broke, bored and with no realistic prospects other than low-paying menial jobs, Morocco’s ‘invisibles’ linger their days away on the few desolate industrial sites the government hasn’t bulldozed yet.

I feel for an entire generation’s wasted potential. For the lack of foresight from our nation’s leaders. For these youth whose aspirations might never extend past these shores. For those who, in a last act of desperation, embark on perilous sea journeys to a foreign El Dorado in search of what they fantasize to be a better existence. But Hussein reassures me: “For me, just staring at the Corniche opens up an ocean of possibilities. I like to stare at the migrating birds or planes passing by and imagine where they’re heading”. The power of gratitude… “Raha!”

10 am — 2 pm. We’ve now set up camp on the beach, where we’re joined by a crowd of Hussein’s friends. Greek Gods under the Sharqi sun, they’ve swapped their street clothes for a soccer strip, revealing the width of their musculature. Sun-weathered hair. Skin warm and soaked in iodine. It’s a scene stealer. A postcard-from-the past recalling a hedonistic era. The days when the metropolis served as the playground for intellectual revolutionaries. Where Uum Kulthum, the ‘Voice of Egypt’, once mingled with Samy Elmaghribi, dubbed the ‘Morrocan Aynavour’. Where trail-blazing women — Fatema Mernissi, Aicha Chenna, or Touria Chaoui — pioneered feminism and decolonial thought.

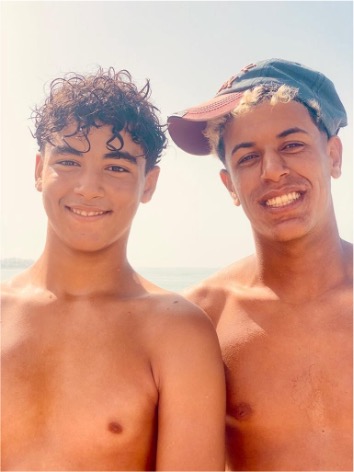

As with most Moroccan boys — divine creatures of eternal youth and imperishable beauty — I cannot place their age. They exude a Peter Pan allure; perhaps due to their impetuousness towards authority, or the way they delight in the mundane with juvenile candour. Their big brown eyes, warm like the incandescent hue of melting chocolate, bear an adolescent glimmer. Upon closer inspection, however, the lines of strain around their mouths and eyes, and hardened expression etched on their faces, let transpire years of toil and hardship. Eerily similar to Hussein’s story, they tell me the beach is the only place where they’re embraced, not cast out. Fancy cafés, which routinely charge steep prices, are out of reach. The swanky malls refuse them entry. “If we’re lucky, they allow us to look at designer stores from afar,” jokes Achraf, a cheerful 21-year-old aspiring graffiti artist who’s been working as a garbage collector since moving from a far-flung village near Ouirgane to the city.

Local children playing makeshift games using whatever they can find — sand, sticks, plastic bottles, used surf boards.

The boys joke about it. But the injustice sits at the limit of humour. With the Corniche just a stone’s throw from the port, the spot offers only temporary respite to these youngsters looking to sidestep boredom and misery, drugs or abuse. Yet, as ever, I am stupefied by their disarming dose of self-derision. Something beautifully, achingly familiar about Moroccan resilience; we laugh even as we weep. I stare at Achraf as he sprints towards the ocean, undeterred by the treacherous salmon rocks and viperous tidewater. “Raha!”

Childhood friends Acharf (left) and Nassim (right)

2 pm — 7 pm — The rest of the afternoon alternates between viciously competitive soccer games, naps under the palm tree shade, and ambient trip-hop pouring from speakers — North African classics such as reggae, raga and chaâbi. Occasionally, time momentarily stops at the distant sound of prayer calls from the nearby minaret, gently lulling worshippers into the mosque. We indulge in the devotional adhan melodies; a humbling reminder of Man’s cosmic insignificance. Children are playing makeshift games using whichever they can scavenge — sand, sticks, plastic bottles, recycled foam boards. As the sun intensifies and the Atlantic swell grows more ardent, attracting the most intrepid surfers, beach-goers are now struggling to plant umbrellas and plastic chairs on the last strip of the Corniche that’s still free to the public.

Later, Hussein offers to fetch a few bocadillos, a hoagie-style street sandwich, from an improvised Mahlaba stationed at the entrance of the beach. In typical Arab fashion, lunch lasts hours, punctuated by a few mint tea interludes. Anass, a former national wind-surf champion from Essaouira and familiar presence around the Corniche, teaches me how to make Sahrawi tea the “proper Amazigh way”. I watch the atay boil over hot charcoal, as Anass tells me about his early days as a struggling athlete: “I’d spend hours picking up trash on the beach and bring it to local surf shops. In exchange they’d give me old boards to practice”.

Anass, shot by the author during a tour of the surf shop where he works by the Corniche

These accounts signal that the ‘left-behinds’ enjoy disproportionally fewer public spaces. A shortage of basic social infrastructure, such as parks, playgrounds and sports facilities amongst other cultural assets. Despite these realities, the boys exhibit a refreshing brand of optimism — one rooted in perseverance and resourcefulness. “We try to make the most of the places available for us to meet and engage in community life.” The power of perspective… “Raha!”

7 pm — 12 am. We’re wandering the Old Medina and each turn down a new alley provides a fresh photo opportunity: a tightly- packed medley of shops selling everything from fresh spices to used electronics, cafés so packed they’re pouring crowds onto the curbs, and tuk-tuks struggling to make their way amidst the clatter of the souk. A patron lures the group inside one of the many hole-in-the-wall bars. Posters of Leon Sultan and Ali Yata — two emblematic figures of the Moroccan Liberation and Socialism party in the 1960’s — adorn the walls, giving the place a communist flavour. The owner stands languidly beside us, cigarette protruding from beneath his moustache, reminiscing about a time when political activists and militants secretly convened in his basement to re-imagine a one-world utopia.

One of the medina’s many hole-in-the-wall shops, all interconnected by curving tunnels.

As the night progresses, patrons gradually migrate to the pavement where people squeeze around communal tables to mix with drinkers from neighbouring bars. The crowd continues to spill out onto both sides of the street. Most remain outdoors even as it gets chilly, huddling under awnings to nurture their cigarettes, chatting the night away in a blend of French, English and Darija amongst other distinctive Moroccan patois. The sweet symphonies of spoken Berber languages Tashalheet and Talifeet…”Raha!”

1 am — 3 am. It’s now late, and the boys — invigorated by the trust built over the day — spend the next hours detailing their day-to-day lives. What comes out are stories of herculean resilience. Perpetual hunger, the struggle for affordable housing and worrying about needs as basic as proper shoes and warm clothing. For Mohcin, a 23- year-old who found himself unexpectedly homeless during the Covid-19 pandemic after his father could no longer support their household, the experience felt disorientating. “As long as I remember, getting access to food and shelter has always been complicated. But since the lockdowns it’s become harder.” The majority lament similar ordeals, including the lack of wrap-around services to improve social safety. It’s a war waged by the dominant class — as the 1% add on to ever-increasing private debt making use of wild speculation, the appropriation of public resources and subsequent breakdown of social protection. “Leaving us [the poorest] to shoulder the cost while a few lucky ones enjoy their fiscal paradise.”

They also talk about the implicit, symbolic violence of poverty; beyond “the obvious economic domination”, as Hussein puts it. The ostracization and feeling of ‘otherness’ from having their lack of ‘socio-cultural riches’ reflected back onto them. Not being ‘polished’ in the ridiculously pontifical art of conversation and manners, of coteries and associations, of educational prestige and expensive hobbies.

Jaafar, a bold and vivacious 22-year-old who taught himself graduate-level sociology to score a vocational training in a prestigious French business school, describes the incomprehension (and rage) he felt when wealthier peers acted genuinely surprised that Jaafar had never been to Varsity ski. Or that he could not cover the €200 fee for the May ball.

In other instances, he was left out of chess club because they assumed Jaafar “wasn’t into that stuff” rather than understanding that ‘no one taught me growing up. I did not even know it existed’. He tells of ‘cool, rich kids acting poor’, “dressed in rags [..] chastising anyone who does not make their own Kombucha”, throwing “disgustingly opulent parties that appropriate third-word or ghetto culture” as they drive up gentrification in traditionally poorer neighbourhoods. “All they’ll ever know is a fantasy world of great fairs and exhibitions, travels, mundane dinners, enchanted childhoods punctuated by countryside escapes, the joys of organic home-cooked meals, berry picking, mushroom hunting and nocturnal swims [..] What do they know about living off food stamps, cramped in a one-bed house with no distraction or pastime other than wasting your sanity in front of the TV?”

1 am. Hassan II mosque out of focus.

These incidents capture a dark reality; that of a close-knit elite, which exerts — willingly or unconsciously — a form of power that is simultaneously subtle but violent. One which is keenly aware of external allures, socialising together in exclusive settings that serve as points of condensation for polishing networks, and which ultimately functions in ‘co-opting mode’, deciding who can be part of these circles. What transpires is the absolute nullification of interactions amongst classes. Socio-cultural separatism rooted in totalitarian rejection of anyone perceived as non-valuable “…ultimately rendering us, and our struggle, invisible.” A tautological loop whereby some are expected to play a lifetime of catching up, proving their worth to institutions, while simultaneously being shamed for not meeting standards of excellence. Doomed to never belong.

This juxtaposition of economic wealth and social affluence — such as connections in high places — is constantly working insidiously against lower classes. The disengagement from lacking a ‘support system’ to guide them through school applications, the absence of a ‘network’ when searching for a job, not knowing how to write a CV. Jaafar looks back on the series of tone-deaf remarks from university peers; being told “he could start his own business to get out of poverty”, he’s “not a risk-taker” or people looking down on him for working menial jobs instead of pursuing his passion for academia. “These people cannot comprehend that not everyone enjoys a financial safety net to take on jobs you like. I have zero ownership on career or life trajectory.” By lacking access to ‘social wealth’ — like exclusive youth clubs, elite universities or acquaintances in eminent positions from business to politics, arts and letters — the poorest get locked in a disadvantage which may take a lifetime to overcome. “Plus, if you’re not of value to them, no one will help. It’s all transactional, mobilised in the pursuit of their own interests.” No such thing as kindness without return.

The irony lies in the arbitrary nature of such social order. “Some won the genetic lottery, act self-righteous about what they think is a successful life […] but they could’ve been born in my slum”, opines Hussein. The judgmental attitude amongst the privileged seemingly boils down to a misconstrued belief that “blue collar people lack work ethic”, chips in Mohcin. A myth the wealthiest have not only internalised, but actively perpetuate through the toxic positivity mantra ‘you can achieve anything, if you work hard enough’.

Mohcin, standing proudly in front of the camera

This idea of meritocracy, illusionary at best, eclipses an uneven playing field: systemic inequalities in access to education and job opportunities; jumping through immigration hoops; food insecurity which keeps a racialized underclass trapped on cheap food and empty calories; financial stress and the harmful consequences — academic, personal and medical — of constantly overriding body and mind limits. All mechanisms of oppression that take place at the intersection of race, gender and social class.

This psychological aspect to precarity and inequality — such as mental health — is discussed at length. The “exploited” know there is nothing natural about class hierarchies. Yet, “to be denigrated [directly or implicitly] profoundly affects the mind and sense-of-self”. Some recall the overt disdain of bouncers outside shops and cafés, like 22-year-old Nassim, who was refused entrance into a bakery “despite showing I had the 5 euros to pay for the pastry [..] I just wanted to treat myself to a tart.” He details the “tingling in the hands [..] and pit in the stomach from the humiliation” — showcasing the intangible yet pernicious ways class violence manifests in the psyche and physical level.

Lahbib, a teen wise beyond his years, notes that “the more privileged, their bodies become of a certain kind [..] they’re marked differently because of the nutritious food they eat”. The naïve reflections of a kid going through life always hungry. These socio-economic fractures ultimately morph into physical and spatial distance amongst classes. “The urban space is designed for the rich,” interjects Hussein. This is true in regard to housing segregation — “the poorest are rendered invisible in the eyes of the richest” due to virtually zero social interactions across income brackets. As the lifestyle choices open to poor people remain far more constrained than those the wealthier can pursue, the latter are able to monopolise lands to grow their own organic food, privatize oceans for exclusive use, spend time in nature for leisure, prioritise wellbeing through fitness, or escape to far-flung havens in times of crisis — as many have done during Covid-19. A freedom of social and geographic mobility the boys cannot dream of as they endure the patronising tone of employees at the bank or visa centres; the interminably suspicious line of questioning when attempting tasks as simple as applying for a loan or wishing to pursue an education abroad. Visa restrictions mean “I have no control over the jobs I take, let alone moving around for leisure,”, says Hussein.

The bubbly and luminous Lahbib, through the lens of the author’s Hasselbad.

Surprisingly, the boys do not feel they’re missing out. They choose to live by the old adage that a good life comes from altruism, purpose and community – with a responsibility to care for each other. The delusive nature of hedonistic happiness, hoarding wealth, and the inherent selfishness in pursuing pleasure at the expense of other human beings and the planet;

“None of this makes sense. A good life is about empathy. That’s how you cultivate abundance. That’s the power of Raha!”

5 am. Sunrise. The crowd is still boisterous and on the move; relishing the last of Casablanca’s al fresco nightlife. Syrian refugees from a war not far away, are ducking between tables, badgering the last-remaining drinkers to buy some roses. A street artist from Cameroon — self-taught as we learn later — adds the final touches to a portrait painted on scavenged wood. A comicotragic picture takes form: ‘Ad-dār al-Bayḍā’, the arab name for ‘Casablanca’ in homage to the ‘white tower’ that guided 19th-century passing sailors who stopped by the metropolis for its art and culture scene — now stands as the parkway of broken dreams for disillusioned artists, poets, writers, musicians. The shattered aspirations of an entire generation.

Sunrise in Casablanca, Morocco

Yet, here they are, bringing the streets to a standstill until the early hours of the morning. The beautiful sight of the Corniche boys. Melancholic, wistful. Simultaneously nervous but desirous to see what the future holds.

Conspicuously resolute in the face of adversity. Brimming with optimism rooted in the certitude and knowledge — passed on by their elders — that a meaningful life lies in our collective humanity. The power of ‘Rahaaaa’, the way the boys utter it, extending the ‘a’ akin to honey melting in their mouth.

‘Raha!’… a reminder to lean into the delicious accumulation of small joys, the little things that once were and shall always be. The fresh taste of watermelon on the first day of summer. Post-nap mint tea. The perfume of the sea mingled with the sandalwood and coconut-spiced undertones of sunscreen and monoï oil. The familiar, comforting memory of rattan furniture in my grandmother’s house. The olfactory titillations of grilled fish and kofte bocadillos. The last choco-almond Cornetto on the beach. Birds chirping in the morning, mosquito bites on the way back from a friend’s house on a humid summer evening. Open-air terraces and crowded cafes, all connected by disorientating tunnels and lit in startling colours. Long, easy summer nights as streets come alive with revellers and peddlers…“Raha!” as we fall in love with Casablanca again.

It’s in these ephemeral moments, transient morning scenes — both frenetic and fickle — that Casablanca’s beauty is revealed. The city can be seen in the lights reflecting off the Atlantic Ocean, its expansive sweep from beyond the Corniche and to the lighthouse. As clear as the bluest sky. Freed from its severity. A picturesque vista. At times, the free oscillations of the sea mirror “my hopes and fear that time might escape through my fingers”, muses Hussein. “But mostly hopes and dreams”… a final testament to Moroccans’ unwavering optimism.

Photographs by Soukaina Rabii with support from and thanks to Rwina.

* This statistic is from an interview with Dr Driss Ouaouicha, president of Al Akhawayn University. There is a lack of accessible data on youth unemployment in Morocco. This report found four out of five unemployed Moroccans are aged 15-34, while this report estimated youth unemployment at 32% in 2022. This report by the International Labour Office (ILO) also finds high rates of youth unemployment, particularly in Morocco’s urban areas.

Read more: