“I hate fishing – but was hooked” exclaims the latest review of Kings of the Yukon. Previously writing for Lacuna about whaling in Alaska and the reintroduction of wolves to Scotland, here Adam Weymouth recounts his latest quest, canoeing for months alongside the salmon of the Yukon River.

I first travelled through Alaska in 2013 with a brief of exploring stories of climate change and resource extraction, and I found no shortage of them: the site of the Exxon Valdez oil spill, 25 years on; Newtok, slipping away into the sea as the permafrost beneath it thawed; Chicken, where gold miners from across the state came to celebrate the Fourth of July.

I had read about a man called Mike Williams, chief of the Yupiit nation, who had spoken widely about the climatic changes that his people were experiencing.

He invited me to his village, far out on the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta.

All flights to the delta pass through Bethel, and it so happened that whilst I was in town Mike was coordinating the trial of 23 Yup’ik fishermen who were in court for catching king salmon during a fishing closure in the summer of 2012.

“Gandhi had his salt, we have our salmon,” Mike said to me.

The closure had been implemented by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game as king salmon numbers plummeted, unexpectedly and inexplicably.

The fishermen pleaded not guilty. They were justified in fishing, so they said, because the taking of king salmon was part of their spiritual practice, their cultural heritage.

Getting caught had not been an accident: they had press released their intentions before setting out. Yet the state argued, successfully, that with king numbers at a fraction of what they once were, there was sufficient need to enforce a ban.

The fishermen were convicted. There were tears in the courtroom.

Back in England I kept an eye on the story, and in 2014, and then again in 2015, the ban on kings was extended to the entire Yukon River, an unprecedented move.

I felt there was a larger story to be told.

Adam’s canoe on the Yukon River

It was the beginning of a long fascination with a fish which I had never considered before. The more that I studied the king, the more that they enthralled me: how they found their natal streams navigating by their sense of smell; how they could straddle both fresh and saline environments; how the nutrients they brought from the oceans inland would nourish an entire river’s ecosystem, their carcasses breaking down into the soil and being drawn up into the trees, so that by looking at the condition of a forest, one could gauge the state of a salmon run.

I had already seen in Alaska how entwined the salmon was with people’s lives, whether that was families piling into the car on the Fourth of July weekend to go catch a few for the deep freeze, or indigenous societies that had evolved over millennia in coexistence with the harvest.

If I was to try and better understand the North, I thought, then perhaps I should go looking for one of its most iconic species, the royalty of the river, before it was gone for good.

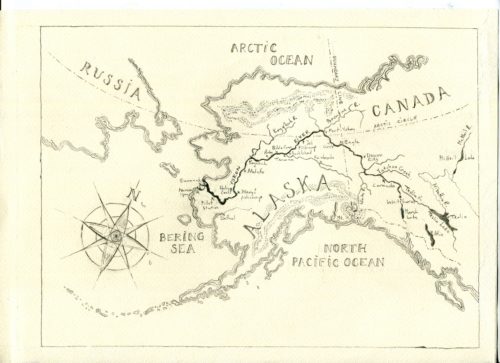

The Yukon River is the longest salmon run on the planet. Rising in northwest Canada, it bisects Alaska, and bythe time it reaches the Bering Sea it stretches seven miles from bank-to-bank.

The kings arrive at the river’s mouth from somewhere deep in the Pacific, and those that travel furthest will then swim 2,000 miles upriver, against the current, to reach the spawning grounds of their birth.

It is one of the planet’s great migrations, and like many of the others, it is now dramatically in decline.

The king has threaded together the communities that live along the Yukon for millennia.

It intimately connected the lives of a Tlingit Indian at the river’s source and a Yupik Eskimo on Alaska’s coast, 2,000 miles away, long before these people were aware of each other’s existence.

It is a link to peoples’ ancestors and their hope for their children’s children.

Many of the Yukon River’s villages, once the sites of seasonal fish camps, remain hundreds of miles from the closest road, and unless going by plane there is no way in but for the river.

Travelling by canoe at the same time as the king run and covering the same path as the fish, albeit paddling in the opposite direction, I hoped to better understand what is changing, not just in the life of the river, but in the lives of the people that depend on it.

And I wanted to see how one of the most remote regions on the planet is experiencing the climatic and economic forces that are shaping the rest of our world.

I had made long, slow journeys across countries before – in 2010 I walked from England to Istanbul – and I found this way of travelling revealing in the interactions that it opened up and the stories that people shared, the trust that people placed in me because I had come from a village that they knew, was heading somewhere they had been.

Now I wondered whether such a journey could also shed light on what was happening to the Yukon’s kings.

Now I wondered whether such a journey could also shed light on what was happening to the Yukon’s kings.

For four months I paddled from the source to the mouth of the longest free-flowing river in North America.

I spent time with gold miners, Athabascan grandmothers, village chiefs, salmon biologists, missionaries, dog mushers and reality TV stars.

I fished with people and cooked with them. I helped three generations of one family tend the fire in their smokehouse.

And I listened as people told me how they found themselves facing a decision almost too stark to navigate: whether to stop fishing in an attempt to preserve the king, or to keep fishing to keep hold of the culture.

And I listened as people told me how they found themselves facing a decision almost too stark to navigate: whether to stop fishing in an attempt to preserve the king, or to keep fishing to keep hold of the culture.

All across the northern hemisphere, salmon have practically vanished.

Kings of the Yukon by Adam Weymouth

In Ireland they were once so plentiful that they were hunted with dogs.

The River Salm in Germany, after which the salmon is thought to have been named, has no salmon anymore.

Overfishing, industrialisation, deforestation, dams and salmon farms have decimated runs.

In many ways, Alaska is only iconic for salmon because it’s the only place that salmon survive. And now these too hang in the balance.

The decisions made along the Yukon in the coming years will determine the fate of one of the last great salmon runs in the world.

And in a place where the salmon is the lifeblood of the people and the land, it will determine much more than that.

Pictures and map by Ulli Mattsson

- Kings of the Yukon is published by Penguin Books.

- For content like this direct to your inbox once a month, subscribe here.