Intensive farming has devastated the bee population in the Yucatán Peninsula. Jennifer Kennedy and Richard Arghiris relay the story of Mexico’s historic Maya beekeepers, the impact of pesticides on their sacred practices, and what is being done to resist the destruction of their culture and livelihood.

In the cool, quiet twilight before dawn, Benjamín Ye Acosta and his youngest son set out from their community of Suc-Tuc in the municipality of Hopelchén in the state of Campeche – a renowned centre of apiculture in Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula. The previous day, he had found his hives brimming with honey, signalling the advent of the annual harvest.

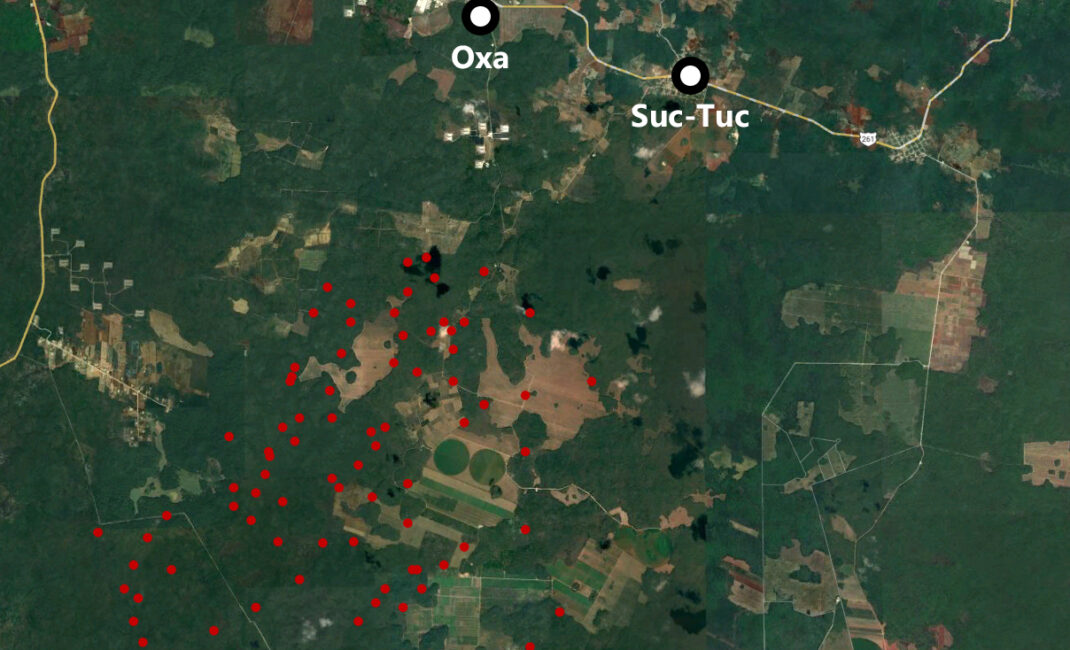

A Google Earth satellite image showing tree coverage and land use in and around the die-off zone (August 2023). Red dots indicate apiaries with dead hives as reported on 23-24 March 2023 (source: Vides Borrell et al, 2023).

They followed a roughly hewn backroad through a patchwork of parched thickets and cultivated fields. Soon they arrived at their apiary – one of dozens in the area owned by Indigenous Maya families from Suc-Tuc and Oxá – and found their bees destroyed.

Seated in a bodega belonging to José Manuel Poot Chan, a friend and fellow beekeeper, Ye quietly recalls the events of March 22, 2023:

“It was something tremendous. My youngest said to me, ‘Look, the bees are on the ground’. And I started to put on my veil. He says, ‘Why do you want the veil? The bees are dead. They’re dead.’”

“We were in shock,” agrees fellow beekeeper Poot Chan, dozens of empty hives stacked up behind him. “I’m ready to harvest and the only thing I see are dead bees, which means there can be no harvest. The space is polluted. And what does that mean? Lack of resources, poverty, misery. Everything comes into our heads. We were in shock. The helplessness of it.”

Impacting no fewer than 80 beekeepers, 110 apiaries, 3,365 hives, hundreds of thousands of honeybees, and an unknown number of wild pollinators, the die-off in Hopelchén proved to be one of the worst in the history of Mexican apiculture. It has cost beekeeping families around 13,200 days of rural employment and nearly 13 million pesos ($775,000 US dollars) (Vides Borrell, González Tolentino and Vandame, 2023).

Hundreds of thousands of dead bees lay scattered around the apiaries. Credit: Collective of Chenes Maya Communities

To determine the causes of the event, a team of bee specialists from The College of the Southern Frontier (El Colegio de la Frontera Sur or ECOSUR) – a public science research institute specialised in sustainable development solutions – visited 18 of the impacted apiaries and collected 16 samples of dead bees for forensic analysis.

Lab tests showed that the bees died from pesticide intoxication, specifically from the insecticide fipronil. Considering the spatial distribution of the impacted apiaries, the varying concentrations of fipronil detected, and the wind conditions on the day of the event, the source was most likely an irrigated maize crop just to the east of the die-off zone, according to the scientists (Vides Borrell et al, 2023).

Despite the scientific evidence backing these claims, for unclear reasons, the Mexican authorities have yet to competently investigate the die-off, or to provide any financial support to struggling Maya families, say the beekeepers.

MEXICO’S LONG TRADITION OF BEEKEEPING

Mexico has produced honey for export since the second world war when a global sugar shortage stimulated international demand for sweeteners. The lion’s share of production has always fallen to the Yucatán Peninsula, where a deep green mosaic of biodiverse tropical forests provides the floral resources for a characteristic dark honey with complex flavours.

In fact, the Maya of the peninsula have practiced beekeeping with native stingless bees for thousands of years. Species such as Melipona beecheii, known locally as Xunan Kab, the Royal Lady Bee, were kept for their products and pollination services long before the introduction of Apis mellifera, the European honeybee, in the 19th century.

Today, Xunan Kab continues to be kept on Mayan patios, but it is exclusively Apis mellifera, a tenfold more productive species, that provides for Mexico’s formidable honey trade.

José Manuel Poot Chan and Benjamín Ye. Credit: Richard Constantine Arghiris

Steered by a loose network of local families and rural cooperatives, commercial beekeeping on the peninsula has been a decentralised industry since campesinos [smallholder or tenant farmers] seized control of production from elite landowners in the 1960s. Poot Chan, who has worked with bees for more than 50 years, is descended from a line of Maya beekeepers.

“It’s my life, my wife, my family, and it gives me sustenance,” he says. “When honey production begins, many of us have a custom of offering thanks. I got to see this with my father and we follow it as a tradition. The whole family prepares to receive the harvest.

“These customs are inherited from generation to generation. It is something very deeply rooted in the mind, in the heart, so when we arrived to see a pile of dead bees, there was a mixture of fear and anger. It was a very ugly moment.”

Indeed, Poot Chan’s forebears might struggle to recognise Hopelchén today, despite the faithful endurance of beekeeping traditions.

Beekeepers were preparing for the annual honey harvest when they found their apiaries destroyed. Credit: Collective of Chenes Maya Communities

THE IMPACT OF INTENSIVE FARMING

Geographically, the municipality corresponds to the Chenes, a place of natural wells and abundance, a land “blessed and cursed with the best soils of the peninsula”, according to Irma Gómez González, a rural development specialist who has worked with Hopelchén beekeepers since 2010.

Neoliberal policies have transformed the Chenes and its cultural landscapes, she says. The changes started after amendments to Mexico’s agrarian law in 1992, which allowed federal and ejidal lands (state-owned lands with communal usufruct rights) to be privatised for the first time.

Mennonites – members of a German-descendent, radical Anabaptist sect who practice US-style intensive agriculture – were induced to settle those lands to exploit the fertile soils and ‘modernise’ the practices of the Chenes Maya.

“The whole production system has changed,” says Gómez González. “It’s very difficult to find traditional milpas [fields cultivated for time-honoured Mesoamerican food systems] and the beekeepers have been having increasing problems.”

As a method, milpa uses so-called ‘slash-and-burn’ techniques to laboriously clear small-scale patches of cultivable land from the jungle. Those plots (or milpas) are planted with traditional cultivars and, after a few cycles, left to regrow as secondary forest. Sown with heirloom squash, maize, and beans, the milpa has provided for generations of Indigenous Mesoamericans, the Chenes Maya among them.

In recent decades, however, government programmes and subsidies have stimulated a cultural shift towards the mecanizado – a large-scale plot that utilises intensive or industrial methods.

An old agricultural sprayer with a rear-mounted boom. Hopelchén, Campeche. Credit: Richard Constantine Arghiris

The mature mecanizado is a wide-open space with uniform rows of mechanically managed, chemically treated monocultures such as soybean, maize, and sorghum, much of it destined for livestock feed and international markets. Mechanised plots use modern technologies and economies of scale to maximise output and efficiency, making them far more lucrative and less labour intensive than milpas, but much more hazardous for the environment.

Where milpa integrates the principle of succession – the process by which a forest regrows and establishes its biological communities after disturbance – intensive agriculture aims to confront and dominate ecological processes, pushing them beyond their natural limits. Where milpas always return to the jungle, clear cutting for mecanizados tends to be permanent, and many end their productive lives as depleted cattle pastures.

According to Global Forest Watch, an open-source online platform that monitors global deforestation, Hopelchén lost 227,000 hectares of tree cover between 2002 and 2022 – an area larger than the West Midlands and Greater Manchester combined; or, in US terms, an area roughly equivalent to Jacksonville, Florida. Around a third of the loss (76,000 hectares) was primary humid forest.

Meanwhile, the savanna, a unique Chenes grassland ecosystem, has mostly disappeared, and seasonal watering holes called aguadas have permanently dried out.

DEFORESTATION, WATER SCARCITY AND PESTICIDES

Deforestation, land levelling, over-abstraction of water, and the drilling of infiltration wells, many of them illegal, have all modified local drainage systems and reduced Hopelchén’s resilience to natural disasters, such as Tropical Storm Cristóbal in 2020. Hovering over Campeche for three days straight, the deluge swept away homes, roads, crops, and thousands of beehives.

Geologically, the Yucatán Peninsula is one vast, flat, highly porous limestone shelf. Its freshwater aquifer – the only source of potable water in the region – is extremely vulnerable to contamination.

Maize monoculture in the municipality of Hopelchén, Campeche. Monocultures utilise economies of scale but are susceptible to plagues and diseases. Credit: Collective of Chenes Maya Communities

According to Ángel Gabriel Polanco Rodríguez, a researcher working on water pollution and public health at the Autonomous University of Yucatán (Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán or UADY), pesticides have entered some public water supplies and are posing risks to human health.

Glyphosate, a pesticide classified as ‘probably carcinogenic’ by the World Health Organisation in 2015, has been found in the groundwater, drinking water, and urine of farmworkers in Hopelchén communities. Similarly, ‘dangerous concentrations’ of organochlorines such as DDT have been found in cenotes [sinkholes] in Yucatán State.

Such pollution may be causing fatal illnesses. “Several water monitoring and biomonitoring studies have found very high levels of pesticides in the blood and breast milk of Maya women with cancer,” says Polanco.

Meanwhile, food chains appear to be contaminated too. In 2022, the Centre for Research and Assistance in Technology and Design of the State of Jalisco conducted tests on 26 samples of fruit and grain taken from markets and production centres in Hopelchén.

They found residues of 32 different pesticides, more than half which are highly dangerous, according to the researchers.

Of course, the true number of pesticides being deployed in the region may be much higher. In 2015, the Pesticides and Alternatives Action Network (Red de Acción sobre Plaguicidas y Alternativas en México or RAPAM) surveyed 20 farming communities in the Chenes and found 74 different pesticides in use. Forty-four have been classified as highly dangerous by the Pesticide Action Network, nearly half are banned in other countries, and 54 are highly toxic to bees.

A carpet of dead honeybees. Fipronil attacks bees’ nervous systems causing seizures, paralysis and death. Credit: Collective of Chenes Maya Communities

Yet those agrochemicals represent only a fraction of the inputs available to farmers. Dave Goulson, a bee ecologist and a professor of biology at the University of Sussex says:

“We’ve somewhere in the region of a thousand different active ingredients on the market available to farmers in North America. It’s pretty hard to disentangle which particular ones might be the most harmful.”

In the case of Hopelchén, all the samples collected by Ecosur tested positive for fipronil, a broad-spectrum pesticide that attacks the nervous system of insects.

According to the European Food Safety Authority – a European Union agency tasked with providing scientific food chain advice to lawmakers – fipronil poses a high acute risk to honeybees. The sale and use of fipronil are restricted in the UK and EU, but its production and export are not.

At sublethal doses, fipronil impairs the motor coordination of bees, disrupts their reproductive cycles, and causes them to abandon their hives. At higher concentrations, it causes seizures, paralysis, and death.

A carpet of dead honeybees. Fipronil attacks bees’ nervous systems causing seizures, paralysis, and death. Credit: Collective of Chenes Maya Communities

According to ECOSUR, the bees in 14 out of 16 sampled apiaries were exposed to a lethal dose at least 2.5 times higher on average than that which would normally kill half a colony.

Mennonite farmers, the usual suspects, could not have been responsible, says Poot Chan, because their farms are situated on the other side of the municipality.

STATE RESPONSES

Poot Chan says the authorities have yet to competently investigate the die-off or to provide financial assistance.

When investigators from the Federal Attorney for Environmental Protection (Procuraduria Federal de Proteccion al Ambiente or PROFEPA) arrived at the scene, it was several weeks after the event and far too late to collect viable samples, says Poot Chan. Since then, the prosecutor has relinquished his involvement and passed the case to a higher authority within the agency.

PROFEPA have not responded to a request for comment, so we are unable to independently verify the beekeeper’s claim that PROFEPS arrived too late to properly investigate.

Read more: “It dried up before our eyes”: How the loss of Jordan’s marshes has fractured communities

Meanwhile, officials representing the state of Campeche have offered what the beekeepers consider to be bizarre, implausible, or inaccurate explanations for the die-off, blaming the weather, the bees, or the beekeepers themselves. The officials have ruled out any financial help.

“The Mexican authorities don’t hear, don’t see, and don’t know anything,” says Poot Chan “That is the result we see to this day.”

“Something that is curious,” adds Ye, “is that after so many meetings with government agencies, there has been no talk of repopulating the hives that died. There has been talk of contracts with the companies that sell chemical products, that these contracts are indefinite because of the amount of money generated, but civil society can’t participate in decisions, in the change of law or regulations, or anything to do with the protection of beehives.”

One problem is the political influence bought by financial inducements, such as those bestowed by powerful agribusiness lobbies. Another is the fragmented nature of Mexican institutions.

At least half a dozen agencies with divergent remits and overlapping jurisdictions have vested political and environmental interests in Hopelchén. Apart from the bureaucratic challenges of coordinating responses, there is considerable ideological disagreement between them.

A mural outside the Casa de la Cultura (House of Culture) in Hopelchén, Campeche. Bees are a large part of the region’s history and biocultural heritage. Credit: Richard Constantine Arghiris

The beekeepers are hopeful that PROFEPA may yet provide compensation but won’t take anything for granted. As such, they recently filed a lawsuit to compel the government to act.

A DECADE OF BEEKEEPER PROTESTS

The die-off is particularly stinging because a landmark legal battle 10 years ago could have brought robust protections to Mexico’s honey-producers.

In 2012, the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Rural Development, Fisheries and Food (Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería, Desarrollo Rural, Pesca y Alimentación or SAGARPA, now SADER) authorised biotech behemoth Monsanto (now Bayer) to plant more than 250,000 hectares of Roundup Ready soybean – a transgenic variety engineered to withstand applications of the herbicide glyphosate (brand name Roundup).

Because EU rules stipulate that imported honey containing more than 0.9% of pollen from genetically modified plants must be labelled as transgenic, the concession threatened to spoil trade relations with the beekeepers’ principal export market.

In response, the beekeepers forged a transnational advocacy network comprised of diverse civil society groups, including national and international NGOs, scientists, journalists, lawyers, and academics.

Maize growing on a commercial farm near the community of Oxa, Hopelchén, Campeche. Credit: Richard Constantine Arghiris

Their efforts crystalised as the Ma’ OGM Collective (Ma’ means ‘no’ in Yucatec Maya i.e. ‘No a organismos genéticamente modificados’) – a dynamic, decentralised, anti-transgenic social movement that stimulated potent Mayan discourses on health and wellbeing, food sovereignty, women’s rights, environmental justice, and political autonomy.

Meanwhile, their legal strategy included the filing of several lawsuits to hold the Mexican government to account.

In 2014, a district court in Campeche ruled in favour of the beekeepers and ordered a state-wide ban on the cultivation of transgenic soybean.

In 2015, Monsanto appealed the decision and was referred to the Mexican Supreme Court of Justice (SCJN). Once again, the law found in favour of the Indigenous beekeepers, with the court ruling that their right to free, prior, and informed consent had been violated.

Read more: The Maya Train and other megaprojects threatening southern Mexico’s Indigenous communities

The outcome heralded a seismic victory for the Ma’ OGM collective. In 2017, Monsanto’s permit was permanently revoked. Then, in 2020, the government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador issued a presidential decree banning the use and importation of glyphosate and transgenic maize, which are to be phased out by 2024.

But despite these victories, nothing has changed on the ground in Hopelchén. Commercial producers are unwilling to change their ways and the authorities do not enforce the law.

ANCESTRAL KNOWLEDGE FOR FUTURE FARMING

Leydy Pech Martín is an internationally celebrated Maya activist, a leader of the Collective of Chenes Maya Communities, a Goldman Environmental Prize winner, a mother, a rebel, and a passionate guardian of stingless bees.

She says the Supreme Court of Justice ruling failed to protect Maya communities from the deleterious impacts of industrial agriculture.

Bees are an integral part of the region’s history and biocultural heritage. Credit: Richard Constantine Arghiris

Faced with recurrent catastrophes such as the recent die-off event, her group is now focussed on winning new rights for bees, on articulating and advocating sustainable alternatives to mecanizados, and on fortifying themselves from within. They are particularly focussed on future generations.

“We have to guarantee that this territory is a dignified territory where they can live, where they can produce their own food, where they can drink clean water, where they can coexist with nature as we did,” says Pech.

“We have a way of life. We want this way of life to be respected and recognised. We have a different way of living because we need our natural resources. We need our ancestral knowledge. We need these medicinal plants. We need the animals. We need the bees. We need everything we have, we the Mayas, the Maya people, the Maya communities integrated with this territory.” She adds: “Let it be a struggle of all of us for life.”

Ye and Poot Chan are not sure how they will survive the rest of the year, but they will continue to demand justice, restitution, and that the government recognises the situation as an environmental emergency.

“There is a pain, an unease in the beekeeping communities throughout the region,” says Poot Chan. “We’ve met with them and they all say the same thing. They say, ‘Right now it’s your turn, but tomorrow it could be ours.’”

FURTHER READING

Vides Borrell, E., González Tolentino, J., Gaspar Ramírez, O. and Vandame, R. (2023) Informe de análisis toxicológico de abejas muertas en Suc Tuc y Oxa, Hopelchén, Campeche, El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, Equipo Abejas [Online] Available at: https://www.dropbox.com/sh/a6ifm5mof5hu27s/AADjVfGVWsijxrYGDpo6h7zXa?dl=0&preview=Informe+muerte+abejas+Hopelch%C3%A9n+2023+-+parte+1.pdf (Accessed 19 Aug 2023) Vides Borrell, E., González Tolentino, J. and Vandame, R. (2023) Informe de análisis preliminar de la intoxicación masiva de abejas en Suc Tuc y Oxa, Hopelchén, Campeche, El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, Equipo Abejas [Online] Available at: https://www.dropbox.com/sh/a6ifm5mof5hu27s/AADjVfGVWsijxrYGDpo6h7zXa?dl=0&preview=Informe+muerte+abejas+Hopelch%C3%A9n+2023+-+parte+1.pdf (Accessed 12 Sep 2023)

Featured image by Collective of Chenes Maya Communities

Read more: