The 966-mile Maya Train being built through Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula is the latest in a series of megaprojects impacting the region, from solar arrays to industrial pig farms. While some residents hope the project will encourage tourism and boost the economy, many others fear environmental destruction on a scale of ecocide and ethnocide. In Yucatan, Jennifer Kennedy speaks with Indigenous communities and activists.

It is a hot, humid day in March 2023 and more than a hundred people have gathered to listen to the testimonies of Indigenous communities impacted by the so-called Maya Train – one of several megaprojects intended to drive the economic transformation of southern Mexico.

At the Tribunal on the Rights of Nature – a citizens’ tribunal meeting on the grounds of an agricultural school in the city of Valladolid in Yucatan State – territorial defenders, academics, and environmental experts speak about how the train is the latest in a series of “megaprojects” threatening southern Mexico’s Indigenous communities.

They say the 966-mile railroad will exacerbate the harm communities are already experiencing from pork farms, industrial agriculture, tourism and renewable energy projects.

The Maya Train map showing seven different sections (from Ruta Tren Maya)

Wilma Esquivel Pat is one of twenty-three Indigenous delegates impacted. She tells the Tribunal: “To talk of nature is to talk of our people. To talk of territory is to talk of our spirituality. We cannot talk of our people, and we cannot talk of our territory in isolation from nature. We are territory.”

Hosted by the non-profit Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature, the Tribunal is formed of five international judges. And although not legally binding, it is an important forum for communities to publicise the destruction of their lands.

As the Tribunal ends, the judges declare that the Maya Train and associated megaprojects are irrefutably violating the rights of nature and of the region’s Maya communities.

The audience cheers and applauds in agreement.

The judges rule that these violations constitute “crimes of ecocide and ethnocide”. Holding the Mexican state responsible, they describe the railway as the “sum of interconnected and large-scale projects with multidimensional impacts.”

Wilma Esquivel Pat testifying at the Tribunal on the Right of Nature: Maya Train that took place in March this year – by Jennifer Kennedy

The controversial Maya Train project is the brainchild of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, whose left-wing populist party Morena won the 2018 Mexican general election. Financed through public and private money, the project is currently estimated to cost up to $20 billion US dollars. The railroad will traverse the three states that form the Yucatan Peninsula – Quintana Roo, Yucatan, and Campeche – as well as Chiapas and Tabasco. It will have seven sections, 20 main stations and 14 substations. According to the National Fund for the Promotion of Tourism (Fonatur), 3,286 households will have been relocated by the project’s completion.

The train is a major infrastructure project that the government insists will promote economic development in one of the country’s poorest regions. It is a key component of the Fourth Transformation – a campaign promise that included reducing violence, ending corruption, growing Mexico’s economy, and building infrastructure.

However, the train has elicited staunch resistance from some of the region’s Maya communities, as well as from civil society, including environmentalists and regional and national NGOs.

Environmental groups have voiced concerns over deforestation, fragmentation of important habitats and destruction of the peninsula’s aquifer, an intricate network of hundreds of caves and cenotes (sinkholes). Selvame del Tren, a group formed of concerned citizens, academics, and scientists in Quintana Roo, has calculated that some ten million trees have already been cut down to make way for the train.

Deforestation on section 6, Tulum to Chetumal, of the Maya Train – by Jennifer Kennedy

Maya communities and organisations have accused the government of human rights violations. The Assembly of Defenders of Maya Territory Múuch’ Xíinbal, which represents Maya communities across the peninsula, says that the 2019 consultation process for the train violated Indigenous communities’ right to free, informed, and prior consent.

Haizel de la Cruz, a member of Múuch’ Xíinbal, says the National Fund for the Promotion of Tourism (Fonatur), the government agency responsible for carrying out the consultation process, only promoted the train’s benefits.

“The people were asked “Do you want a train to come? It’s going to bring you education, it’s going to bring you water, it’s going to bring you hospitals, it’s going to bring your medicines. So, faced with these questions people are going to say yes because ‘that’s what I need, but I’m not saying yes to the train, I am saying yes to the benefits you are offering.”

Section 5, Cancun to Tulum, of the Maya Train in February. Construction work continued despite the order of a definitive suspension – by Richard Arghiris

Indeed, at the time, not a single environmental impact assessment for the project existed. As such, communities lacked the critical information they needed to make an informed decision about the long-term environmental, social and cultural impacts, says de la Cruz. In December 2019, a regional referendum was held, with 92% of votes from 84 affected municipalities cast in favour of the train. However, just two per cent of registered voters participated. Nonetheless, López Obrador and his supporters claimed the result as a victory and proof that the project has widespread backing.

In January 2021, Múuch’ Xíinbal filed an amparo – a type of legal complaint that provides citizens with a mechanism for holding authorities to account for human rights violations. It is one of the tools that territorial defenders have been using in their pursuit of justice.

Múuch’ Xíinbal called for the suspension of work on sections one, two and three. They argued that communities have the right to a healthy environment and to participate in decisions that could impact their territory and natural resources.

The amparo was successful – the court granted a definitive suspension. But despite the court’s ruling, construction work continued unabated.

Construction work taking place at section 7, Bacalar to Escárcega, of the Maya Train – by Jennifer Kennedy

“Under this government not only are amparos not respected, but every time [the courts] give a resolution in our favour, the president announces that he is going to come and take a tour of the peninsula. So, we see that the work shifts are doubled or tripled.

“So, in that sense, the president makes a mockery of us, because every time a suspension is granted, the president comes and says everything is fine, nothing is going to stop,” said de la Cruz.

Fonatur and the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (Semarnat) appealed the court’s decision, and in 2022 the suspension was removed, dealing a blow to the territorial defenders.

The Dama Blanca cenote on Section 5 of the Maya Train by Jennifer Kennedy

To date, more than two dozen amparos have been filed in relation to the train. In February this year, a local NGO called Selvame del Tren won its legal complaint when the court granted a definitive suspension of work on section five.

The court’s ruling was ignored. A Selvame citizen caravan, visiting section five to see two of many cenotes that stand to be damaged or destroyed, found construction workers were easily visible and toiling away. With the first train journeys scheduled for December 2023, work to complete the line is furiously underway. And as Múuch’ Xíinbal and other territorial defenders are keen to stress, the train is the latest in a series of megaprojects that are harming local communities.

De la Cruz says that there are four main project types in the peninsula – renewable energies in the form of solar parks and wind farms, touristic infrastructure, industrial agriculture, and industrial pork farms.

In Homún, a small town in Yucatan State, the community has been fighting for six years to keep a pork farm from operating. Situated in a protected area known as the Ring of Cenotes, so-called for its hundreds of sinkholes, Homún is home to some 7,000 residents.

In 2017, Mexico’s Ministry of Urban Development and Environment (Seduma) granted the company Producción Alimentaria Porcícola (Pig Food Production) permission to build an industrial farm housing some 50,000 hogs near Homún. In response, community members formed the collective Kanan ts’ono’ot (Guardians of the Cenotes) and filed a legal complaint on the grounds that their right to consultation had been violated and that the company’s environmental impact assessment was full of irregularities.

José May Echeverría, Kanan ts’ono’ot’s secretary, said: “One of the most important things we have learned is that we as Maya people, as Indigenous Peoples, have rights and the greatest right we have is the right to say what can and cannot be done in our territory. We have the right to self-determination.”

Kanan ts’ono’ot carried out its own consultation process and a vote in which most voters voted against the pork farm. The community also won a definitive suspension of the farm and other megaprojects inside the protected area.

May Echeverría said their legal struggle was far from over, however. The suspensions are temporary until a court ruling that the community hopes will happen later this year.

Meanwhile, Homún is far from an isolated case. In 2020, a Greenpeace Mexico report found that hundreds of industrial farms in the region have been established with “little or no regulation, a situation that contributes to the impact on the air, soil and water of one of the areas with the greatest natural wealth in Mexico”.

According to the report, there are 257 pork farms in the peninsula registered on public databases, but just 22 of them have submitted environmental impact assessments. In March this year, López Obrador announced that he will issue a decree prohibiting pig farms in the peninsula that contaminate the aquifer. He also promised to close all farms operating illegally.

Section 5, Cancun to Tulum, of the Maya Train in February. Construction work continued despite the order of a definitive suspension – by Richard Arghiris

“Right now, we are seeing what happens,” said May Echeverría. “[The president] said that not one more farm can be opened in the Yucatan, not one more will open and that they are most likely going to regulate them. But we don’t know because there is a lot of corruption and economic interests that are involved in the state government.” At the time of writing, the pork farms continue to operate, despite a recent Semarnat investigation revealing that there are unacceptable levels of water contamination in 13 municipalities in Yucatan State due to pig farming.

In Hopelchén, Campeche, beekeeping communities are battling industrial agriculture, which is impacting their way of life, driving deforestation, and affecting the aquifer.

Section 5, Cancun to Tulum, of the Maya Train in February. Construction work continued despite the order of a definitive suspension. (Richard Arghiris)

José Manuel Poot Chan, a Hopelchén beekeeper, said he thinks the harmful practices of industrial agriculture in his municipality will only increase because the cost of transporting soy, one of the main crops grown in the state, will decrease.

Ana Esther Ceceña, an economist and geopolitical expert at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, said that although the project is touted as a tourist train, it will mostly carry cargo.

In fact, the Maya Train’s general director has estimated that the railway will move two million tons of cargo in its first year. By 2053, it is expected to carry some 12.5 million tons of cargo every year.

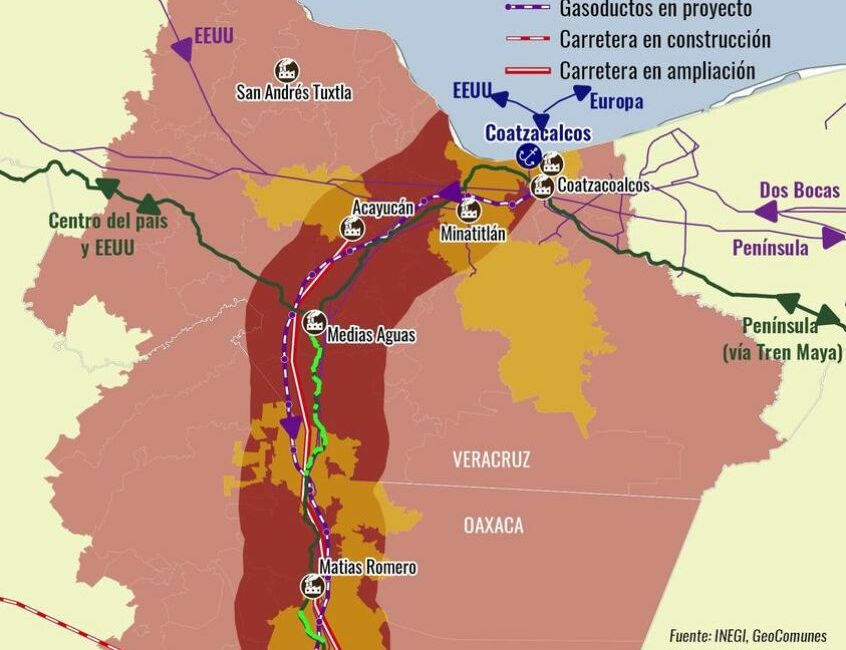

The Interoceanic Corridor (from GeoComunes)

The Maya Train will also connect with the Interoceanic Corridor, a 188-mile railway that will run from the port of Coatzacoalcos in Veracruz to the port of Salina Cruz in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, Oaxaca.

The project includes rehabilitating existing railway lines, developing ten industrial parks and building a gas pipeline. It will attract more than two billion US dollars in investment, according to the government.

Ceceña, who testified at the Tribunal, said that the “Interoceanic Corridor is one of the greatest projects for the reordering of the global circulation of goods”. As such, it will transport oil to international markets, while the “Maya Train will transport oil to the peninsula’s tourist areas.”

Economist and geopolitical expert Ana Esther Ceceña testifying at the Tribunal on the Right of Nature: Train Maya that took place in March this year. (Jennifer Kennedy)

It will also transport commodities such as pork, which is already being exported to China and other countries in Asia.

Plans to transport cargo are connected to the construction of development poles at each of the Maya Train’s main stations. The aim of these poles – which are expected to focus on sectors such as tourism, agriculture, manufacturing, and energy – is to stimulate economic activity by attracting investment and creating jobs.

As such, for people like Luis Roberto Marzoa Merlan – a resident of Candelaria, Campeche, where one of the main stations is being built – there is hope that the Maya Train will bring new opportunities.

Marzoa Merlan said: “I think most people here in Candelaria are in favour of the project. For a long time, this part of Campeche was forgotten – it was abandoned by past government administrations. They didn’t give much importance to tourism.

I think [the train] will bring us many benefits in terms of the economy and tourism because about five or ten years ago Candelaria was not a tourist destination at all, but this government is promoting tourism a lot.”

Marzoa Merlan expressed concern, however, that maybe tourism could also bring insecurity, violence, and organised crime, which currently affect the tourist hotspots of Quintana Roo. He was also worried about the possible impacts of large-scale tourism on important ecosystems like the Candelaria River.

Wilma Esquivel Pat blessing the land on section 6, Tulum to Chetumal, of the Maya Train during La Caravana el Sur Resiste (the south resists caravan) in April – by Jennifer Kennedy

Even so, Marzoa Merlan was optimistic about the train’s arrival and invited visitors to experience Candelaria’s natural reserves, cenotes and archaeological sites. While some of the region’s residents are hopeful that the project will benefit their communities, others are adamant that they will be transformed for the worse.

“We see that this development for us is death,” said de la Cruz. “And not only our death but the death of all of us who live here, who live in the territory. In other words, it is a familiar death that happens when a development project comes. Because we have seen, and not only with the arrival of the train but with other previous megaprojects, that this is what they always do.

“That’s why we say that when they take our land away from us when they dispossess us of the land, they are really dispossessing us of our language, our culture, and our way of life. And our way of life cannot be understood without our connection with nature.”

*Government agencies Semarnat, Seduma and Fonatur have not responded to requests for comment.

Read more: