In Part 2 of his three part investigation, Adam Weymouth goes in search of the place where the last wolf in Scotland was killed. He finds a story of land and change and enduring battle for wilderness in the Highlands and around the world.

Part 2: The Last Wolf

Three days after leaving Alladale I meet Cait McCullagh, archaeologist and curator, in the Inverness Museum. I had crawled from my tent on the north side of the Beauly Firth two hours earlier and rushed across Kessock Bridge with the morning commute to make the meeting. I am feeling a little grubby and dishevelled now that I find myself in public. Cait hands me a cup of coffee.

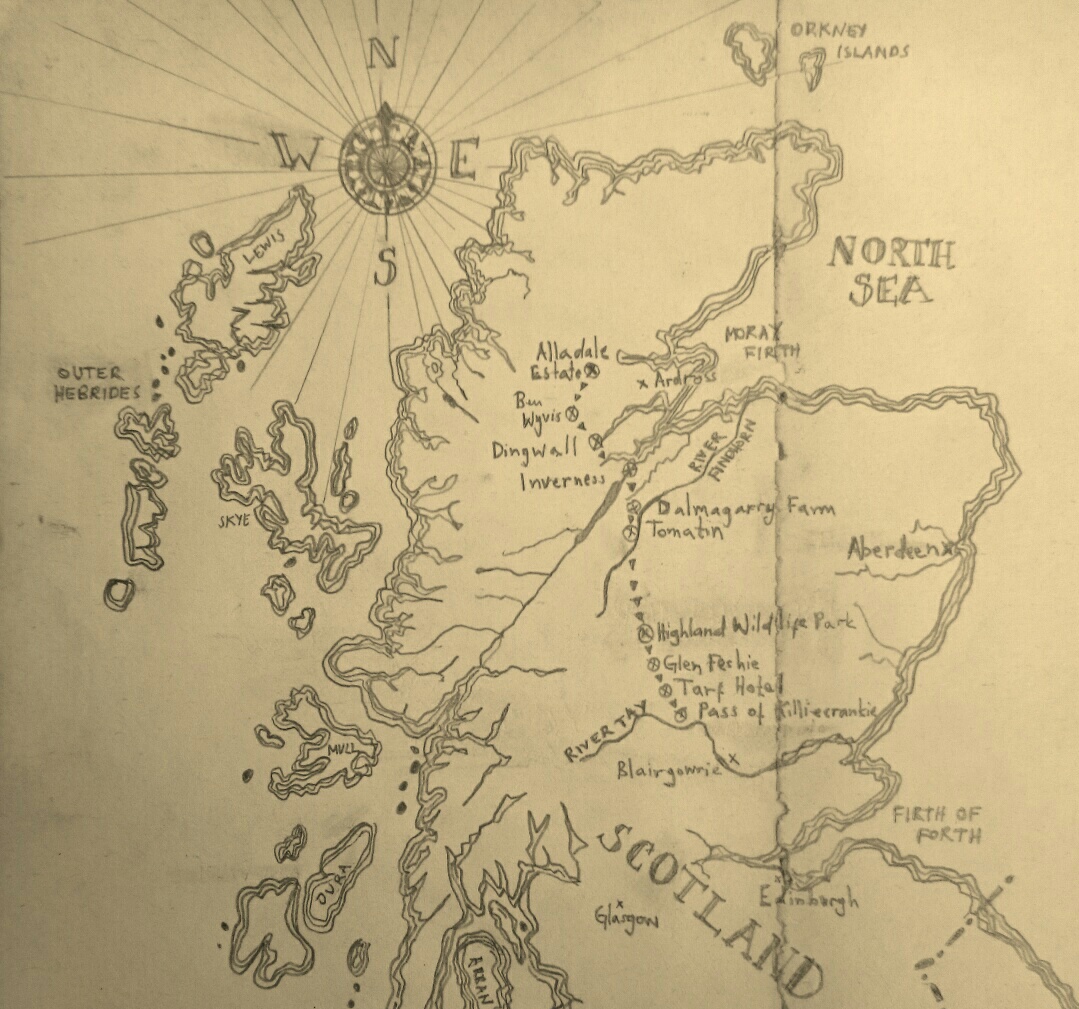

Map of Adam’s walk by Ulli Mattsson

I have come to see the Ardross Wolf Stone, one of the centrepieces of the museum’s collection. It was carved by a Pict, a people, Cait explains to me, who lived north of what is now Aberdeen at the time of the late Iron Age, in the middle of the first millennium. They wrote nothing down, and the little known about them derives from contemporary historians. It was the Romans who called them Picts, thought to mean ‘painted people’, but already we are moving into speculative territory. They lived in settled communities in the valleys, much in the style of early modern farmers, surrounded by arable crops and with some livestock on the slopes. “And that’s it, that’s all we know,” Cait says, six minutes into our conversation.

But what they did leave behind are these carvings. Geometric shapes, discs and spirals and rods, combs and mirrors, flowers, and many different animals. They are domestic or semi-domestic: bulls, deer, horses, birds. The wolf stands alone, she tells me, in being the only truly wild animal in the repertoire. It is a beautiful piece, head down, mid lope, the curves of its line speak of movement and of muscle. “It’s clear from the art that they are people who are hunting these animals,” she says. “There’s an observational quality that I think comes from spending a lot of time with the animal out in the field.”

The wolf stands alone in being the only truly wild animal in the repertoire.

It is the most tangible sense I have yet had that once there were wolves that walked here. I could touch this carving before me, this carving done by someone who had seen a wolf, many wolves, 1,300 years and 30 miles away.

“It’s a time,” says Cait, “when land wealth was important. What we do know is that there’s an emergence of kingship, and this centralising of power to a few individuals is based on the accumulation of land resource.”

The Christianisation of the Picts was lending justification to the notion of a single ruler. One God, one master, imbued with the divine right to govern. There began a shift away from a tribal society to a nascent nation state, along with all that that implies. “Enclosure is happening on a grand scale,” says Cait. “The enclosing of what’s tamed, the land that’s under pasture, the land that’s under arable, the land that’s enclosed within the monastery, the land that’s enclosed within the hill fort. This notion of what’s within and what’s without is strong. And perhaps hunting animals which are out in the wild, perhaps that has some meaning. We’ve inherited an understanding of wolves as being predatory, wild. Maybe the use of the term wolf, and the danger of the wolf, acts as a metaphor for all the other things that people are frightened about. It’s out there. The unenclosed.”

The wolf tempts us towards recidivism, and we choose to hate him for it.

This broaches two of the fundamental reasons why the wolf has been able to exert such emotive power over us since we first put up fences and called one side ‘inside’ and the other side ‘out’. One, that in our coming to have property in the form of livestock, the wolf morphed from a rival with whom we competed for prey into a poacher, a criminal, who took what was rightfully ours. Slighting us, devouring our flocks, was a calculated act that demanded retribution. And two, the allure of the wilds, the seductive terrors that have addled our dreams since we first hung up our nomad’s sandals and planted seeds. When the wolf tells the little pig “let me come in” he does not bark it, it is a voice laced with honey. An old teacher of mine was fond of saying that people are the missing link between animals and civilisation. The wolf, more than any other creature, tempts us towards recidivism, and we choose to hate him for it.

The wolf was once the most widely distributed, non-domesticated land mammal on the planet, except for ourselves, populating the entire Northern Hemisphere from Alaska to Japan, from Mexico to Ethiopia. But almost without exception the crusade against them has been merciless.

Wolves were effectively exterminated in Wales by the end of the first millennium, in large part thanks to King Edgar the Peaceful who levied three hundred wolves a year as tribute from the Welsh, as well as demanding a quantity of wolf tongues as atonement for certain crimes (Powell, 1774: 57). Michael Drayton, seemingly incapable of anything but the passive tense, wrote an ode to Edgar several centuries later:

“O Conquer’d British King, by whom was first destroy’d

The multitude of wolves, that long this land annoy’d;

Regardless of their rape, that now our harmless flocks

Securely here may sit upon the aged rocks.”

In England they had more or less been wiped out by the end of the 13th century: in 1300 the Reverend William, needing “four putrid wolves” for a medical purpose at which we can only guess was forced to import them from abroad, to the displeasure of English Customs (Rackham, 1987: 35).

The wolves continued to be annoying in Scotland for much longer. The final definitive record there is from 1621, a note in the diary of Sir Robert Gordon that “sex poundis threttein shillings four pennies [was] gieven this year to thomas gordoune for the killing of ane wolf, and that conforme to the acts of the countrey.” (Rackham) It is an exceptionally high sum that suggests demand was far outstripping supply. From this point on the stories cross over a threshold into the more shadowed place of myth.

Looking at maps before I set off on my walk, I decided to finish my hike where the last wolf in Britain was killed. It seemed a fitting bookend to Alladale. I chose Killiecrankie because it was the first story that I came across, and I had already begun to plan my journey before I came to realise that Britain’s last wolf is more numerous than the name might suggest, more akin to Britain’s Oldest Pub.

Sir Ewan Cameron, of Lochiel, is reputed to have killed the Killiecrankie wolf. I had found mention of it in Harting’s British Animals Extinct Within Historic Times, who describes how in 1818, when the collection of the London Museum was dissolved, the following item was auctioned off:

‘Lot 832 WOLF, a noble animal, in a large glazed case. The last wolf killed in Scotland by Sir E. Cameron.’ (1880: 175)

I pictured it in the bowels of some Scottish estate, moth-eaten, its glass eyes staring madly, or perhaps as the footstool of some English Laird. And I decided that I wanted to find it. I began to search in the archives of the Natural History Museum.

The London Museum was opened by Edward Donovan, amateur zoologist, in 1807. In the museum catalogue he gives short shrift to his wolf exhibit. “Happily those rapacious creatures, once the scourge and terror of the country, exist no longer in a state of nature in Britain.” It is in keeping with the parlance of the day. Diatribes against the wolf masquerading as biology were practically a genre of their own. One of my favourites is from the Comte de Buffon’s Natural History, 36 volumes of which he published throughout the 18th century. Despite being a remarkable work of scholarship and research, when it comes to the wolf he cannot resist the following: “In fine, the wolf is consummately disagreeable; his aspect is base and savage, his voice dreadful, his odour insupportable, his disposition perverse, his manners ferocious; odious and destructive when living, and, when dead, he is perfectly useless” ([1749-1788] 2007: 209).

Donovan’s Natural History of British Quadrupeds has a chapter on the wolf. With only one in his collection we can assume that what we are looking at, here, is the animal he claimed to be the last in Britain. It is a fearsome beast with an unhinged look, a hint of slaver round its chops. His description waxes, at times, almost Shakespearian. Canis Lupus, he tells us, “frequently commit[s] prodigious ravages.”

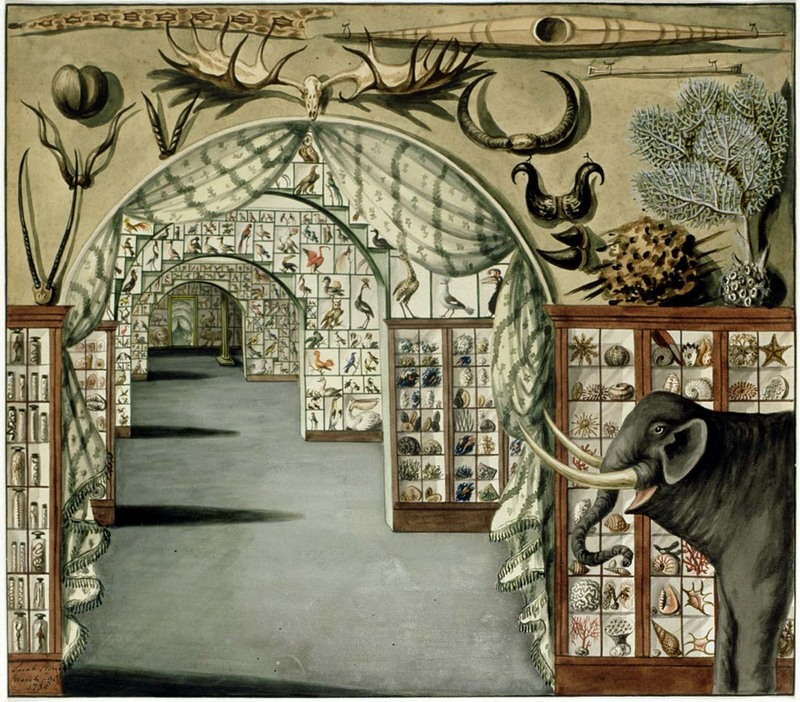

Image by Sarah Stone, via Mitchell Library

The museum had cost Donovan £15,000 to set up, and despite an enthusiastic public, by 1817 he was broke. He attempted to pique the public conscience. “That the dissolution of such a vast repository of the natural productions of Great Britain will excite the regret of every well-wisher to the promotion of knowledge, cannot admit of doubt.” But no benefactor came forward, and in 1818 his entire collection was auctioned off. I found the sale catalogue, but there is no record of who purchased the wolf. I was going to have to look elsewhere.

Sir Ashton Lever’s museum opened in 1775. It was widely recognised as the best natural history collection of its day, but Lever, like Donovan, was less interested by accounts than by collecting. In 1786, bankrupt, he disposed of all 28,000 exhibits with a lottery. The winning ticket was bought by James Parkinson, a law-stationer, who himself beset by financial difficulties auctioned it off in 1806. Donovan bought more items than anyone else. On 30th June, along with “sea otter, young,” “large piece of timber,” “crab, with a number of oyster shells adhering” and “a curious water rat”, he paid five pounds for “the wolf in fine preservation.”

George Shaw made a study of Lever’s collection. The illustration of the wolf must be taken from the same specimen as Donovan’s; see how that front left forepaw is cocked. Yet this beast looks closer to a collie, docile and pastoral.

Shaw is less hysterical in his prose than Donovan, although he does admit that “the rapacity and gloomy disposition of the Wolf have…rendered it the aversion of mankind.” He continues: “the ferocity…is greatly mitigated by an early education; of which the individual specimen from which the present figure was taken, is a remarkable instance; having been rendered in a great degree tame and gentle by the assiduity of the late Sir Ashton Lever.” Donovan’s ravaging wolf, it seems, the last wolf to terrorise Great Britain, was Ashton Lever’s pet.

The Wolf as depicted in Musei Leveriani, Open Library

One can only assume that, on the verge of bankruptcy and with no qualms about misleading a public who had failed to stump up the cash to save his life’s collection, he turned his wolf into The Last in the hope of a few extra quid. Maybe he coaxed those jaws into a snarl. There have always been those that benefited in making the wolf a little more ravening than in reality.

The more one explores the story, the more it falls apart. Even Cameron killing a wolf in Killiecrankie seems to derive from no more than a footnote in a travel book from 1771 (Pennant), a story a century old that the author presumably heard while on the road. What is certain is that Cameron was at the Battle of Killiecrankie, in 1689, as one of the commanders in the Jacobite uprising against the Government, a spectacular victory one month before their rebellion was snuffed out.

There is another last wolf story, this one from 1743, involving a man named MacQueen at a place called Ballachrochin on the River Findhorn. That one is close enough in time and place to the Battle of Culloden to ponder whether significant moments in the crushing of the clans and last wolf myths have a tendency to get conflated. The wolf has always been a potent symbol of wildness and freedom that has only increased with their persecution. Its extirpation could be an analogy for the English civilisation of the Highlands, whilst at the same time honouring the heroism of the last of the clan chieftains, their bravery in the face of the ravages.

The wolf has always been a potent symbol of wildness and freedom

“If you want to stretch the metaphor,” Cait says to me at the Inverness Museum, as both of us gaze at the Wolf Stone, “and talk about the Picts as indices for a past freedom, a state of the Highlands being outwith the control of Southern governments, and it has been used – archaeology is always used as an underpinning for a variety of ideologies and nationalism is certainly one of them – then maybe the wolf is tied into that romantic past as well. There is a romanticism around wolves, and part of the debate around the reintroduction of the species rests in that romantic Celtic twilight.”

Certainly the Clearances could never have happened had the wolf still loomed in the Highlands: vast flocks of sheep with few shepherds to work them was only feasible because they no longer had any predators. And certainly there has long been a tendency to conflate the wolf and the native. A Massachusetts law of 1638 stated that: “Whoever shall [within the town] shoot off a gun on any unnecessary occasion, or at any game except an Indian or a wolf, shall forfeit 5 shillings for every shot.” (Lopez, 1978: 170). Barry Lopez, renowned nature writer, says: “Insofar as the Indian became a Christian and lived like a white man he was accepted; insofar as the wolf became a dog, a pet, or a draft animal in someone’s sledge harness he, too, was accepted. But by 1900 there wasn’t much point being either a wolf or an Indian in the United States” (1978: 170). The wild, the native, the wolf, they were to be spoken of in the same breath. All were God-forsaken, all were required to fold before the inexorable logic of progress.

In the battle for wilderness, as David Brower has said, those that fight against it only have to win once.

And yet these last wolf stories are not entirely lost to twilight. A day’s walk south of Inverness, just shy of the Findhorn and just off the A9, is Dalmagarry Farm, and at Dalmagarry farm, five or six miles from the bend of the Findhorn where MacQueen shot the last wolf, lives a man named David MacQueen.

“My grandfather came into the farm in 1908,” he tells me as we sit in his kitchen and I try not to eat all the biscuits, “although we’d been in the area for generations before that. We originally came from Skye, my forebears, and they came over as protectors for somebody who was marrying into the MacIntosh clan, to keep an eye. About 400 years ago, probably. And we’ve been in this area ever since.”

The MacQueen story was first written down by Sir Thomas Lauder in 1830, 83 years after the event. He describes him as “nearer seven than six feet high, proportionately built, and active as a roebuck.” The MacQueen in front of me looks tough as well, as any hill farmer would be. He keeps 600 head of sheep and some cattle, a fairly average size, he tells me, for a family-run farm round here.

Photo by Adam Weymouth

“The MacQueen who killed the last wolf,” he says, “he’s a great-great-great whatever, you know, of ours. He had a croft down the Findhorn valley there. This wolf had allegedly killed someone, a child, I think it was, and MacIntosh had organised a shoot. They were all to meet at Moy Hall, and this MacQueen who was to head up the hunt was late in arriving that morning. MacIntosh was furious. And when he eventually did arrive he started having a go at him, telling him off, and story has it that MacQueen threw the head of the wolf on the ground. They say that he’d come across him on the way over and he’d killed it. So that’s the story. And as a result of that, MacIntosh was delighted, and he was given his croft rent free for the rest of his life.”

“How true do you think it is?” I ask him.

“Oh, I think it’s true. There was a chap who’s written a book, a journalist, and he was pouring scorn on it. But our family’s been here for generations and it’s been passed down. I’ve no reason to disbelieve it. It’s a link to our past, right enough. And I suppose he was a hero at the time, because these were harsher days. Some people would say I doubt they would attack children, but that was the story, so I don’t know. You either believe it or you don’t.”

The last wolf would have died weak and old, alone, and become no more than carrion.

The chap he refers to is Jim Crumley, and Crumley certainly doesn’t believe it. There are many Last Wolf stories throughout Europe, he points out, and they invariably conform to similar tropes. “The wolf had to be hideously terrifying, preferably huge and black, and had to have killed someone vulnerable. The hunter had to be preternaturally gifted and heroic.” (Crumley, 2010: 66). So far, so good. And as he goes on to discuss, the notion that the last wolf was killed by a human pushes the bounds of credibility. American trappers in the first part of the last century described hunts for outlaw wolves that lasted years: the few that remained had survived because they were smart. The most notorious garnered nicknames. The Werewolf of Nut Lake. Three toes of Harding County. Cody’s Captive. Old Lefty. The Traveler. Ghost Wolf of the Little Rockies. Captured, they were paraded through the streets like the outlaws of the past: Jesse James, John Wesley Hardin. They are shy, elusive creatures, and the last few wolves in Britain, a scattered handful of lone animals, probably lived on for years after the final sighting or shooting. Undoubtedly we pushed the creature to extinction, but it is perhaps giving ourselves too much credit as a species to think that we put the last one’s head on a pike. The last wolf would have died weak and old, alone, and become no more than carrion.

But that is not quite the point. Such stories are not of value for their facts alone. They conjure a version of nature that serves those that inhabited a certain time and place, and being a sheep farmer, as much as being a MacQueen, David has a fairly persuasive vested interest for maintaining the story and the status quo that his ancestor may or may not have helped to put in place.

“It’s all kind of distant folklore,” he says. “It’s only come back to the fore with this idea of them reintroducing wolves. Our memories are quite short.” The number of wolves in Europe has quadrupled since the 1970s, and MacQueen must be turning in his grave.

The spread of wolves through Europe in the past forty years has indeed been prodigious. There are now permanent populations in twenty eight European countries (Nuwer, 2014). There has only been one European reintroduction, in Georgia. The rest have come through their own natural spread. Wolves are travellers. In 2011 a male known as Slavc travelled 2000km from Slovenia, via Austria, to Lessinia in Italy, crossing motorways, traversing mountain passes in the middle of a winter where the snow lay six metres deep, swimming the Drava river at a spot where it was 280 metres wide. In Lessinia he met a female, and he has since fathered two litters (Nicholls, 2014). Big carnivores do well in times of economic and political crisis – wolf numbers have doubled in Russia since the collapse of the USSR as state-sponsored culling programmes ceased – and from there they have spread into Eastern Europe. Some conservationists have suggested that the current economic crisis in the Mediterranean has encouraged their recolonisation, as people in rural areas migrate to the cities and abandon their land to wildlife (Vidal, 2014).

“You’ve got to admire the wolf in the sense of the creature he is,” says David. “But they’re pack animals, and they roam over a lot of ground. I think the world has moved on a bit from the days when things were a wee bit more frugal in the Highlands. I’m just not sure there’s the space for them, to be honest. As a sheep farmer, obviously, I wouldn’t be in favour of them at all.”

David is hardly alone in this. The National Farmers’ Union Scotland is strongly opposed to the idea. The reintroduction of the sea eagle, which began on the Isle of Rum in 1975, has been controversial enough. Despite two reports authored by Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH) which have found the raptor to have “minimum impact” on lambs, (Simms et al, 2010) (Marquiss et al, 2005) farmers living out on the Western Isles claim otherwise. With the eagle population growing by 8-10% a year (Miller, 2014) there are regular calls for culls or even complete extermination. This for a bird of prey which has been definitively linked to taking healthy lambs in only exceptional circumstances. The link between wolves and sheep is somewhat more proven, a rivalry as entrenched in the folklore as that of cats and mice.

“I would be wary about a lot of the reintroductions as a livestock farmer,” David tells me. “We’re not bothered with sea eagles here, but I know other people who are bothered by them. It’s quite soul destroying if you’re wanting people to be farming efficiently, keeping up with the times as it were, having to do certain things, and then you say, oh well, we’re going to put back all these beasts of prey and raptors and they can all just help themselves.”

In Europe compensation is paid out to farmers who have sheep taken by wolves – an average of two million euros annually across France, Greece, Italy, Austria, Spain and Portugal (Monbiot, 2013: 114). But David is sceptical about how that would work here. “You can just see it being a case of arguing about compensation for this that and the other. And it’s not the same, you know, if they take one of your best ewes.”

If livestock are well protected and there is sufficient alternative food, wolves are much more inclined to go for wild animals.

The arguments go back and forth. Those that support the wolf’s return will say it is responsible for a tiny proportion of the sheep deaths in a region: in Italy 0.35%, in Slovakia 1% (The Wolves and Humans Foundation). That is even less than the sea eagle. But that is because wolf numbers remain small for the time being, farmers say, and an individual farm can be disproportionately affected, with wolves sometimes killing many animals in one night in an attempt to make a larder (Monbiot, 2013: 114). Studies have shown that if livestock are well protected and if there is sufficient alternative food then wolves are much more inclined to go for wild animals than domesticated (Wagner et al, 2012), but those whose livelihoods depend upon the domestic find that hard to believe. There are ways to protect your sheep, say conservationists, a mix of old and new techniques that range from fencing them in or keeping dogs with the flock, to collars that monitor the sheep’s heart rate (suggesting distress and perhaps a wolf in the area) and text the farmer to let them know.

When I suggest this to David he tells me that it’s hard enough to scrape a living as it is. “You’ve got the vagaries of the weather against you all the time. We’ve got enough problems with crows and seagulls. So it does annoy you a wee bit when some joker that you’ll see once in a blue moon is telling you how to run the place. They’re maybe showing up on a nice sunny day in the middle of summer, and you’re working the place all year round and putting up with it. That maybe grates a wee bit.”

Outside the sun is shining, and although he doesn’t quite say it, I can’t help feeling that what he really thinks is that there’s one sure fire way, one hundred percent effective, to protect your sheep from wolves, and MacQueen hit upon it three centuries ago.

A short walk up the road from David’s farm, through the morning dew and fields of lapwings, is the village of Tomatin. Outside the shop I meet Allan, a gamekeeper on one of the estates in the area. Along with the livestock farmers, the gamekeepers have been most outspoken against reintroducing the wolf. We climb into his Land Rover and he drives me up to the land where he works. Allan has a face you could strike a match on, sun and wind burnt, a sandy moustache, dressed in army fatigues.

“I’m getting paid to do my hobby,” he says. “I’m supposed to go on holiday. I’d never leave the place if the wife didn’t make me go.”

Photo by Adam Weymouth

We stop on a rise amongst the heather and he shuts off the engine. We sit there, the windows down, the crackle of the skylarks’ song, looking out across forest toward mountains dim and blueish in the distance.

“People think this is a wilderness and there’s tonnes of room up here,” he says, turning to me. “Look at it. All these trees are planted by man. We can’t quite see the Cairngorms, but that’s about the only bit of wilderness in Scotland and there’s people all over it. Wilderness doesn’t exist. Man manages this now. Scotland’s changed forever. Unless they’re going to get rid of the population and have a few hunter-gatherers. The wolves were killed out for a reason. They were a problem, to agriculture and people living in the countryside. That’s why they were done in.”

Allan sees managing the landscape as vital, not as something that should be left to either the wolves or those high up in SNH who never leave the office.

“Everybody wants to get songbirds back to a certain number,” he says, “and all these farmland birds to a certain number. But they forget that when these birds were at their peak, probably 80% of Scotland had a gamekeeper on it. In those days a gamekeeper killed whatever he wanted, whenever he wanted.” If you want songbirds, you need to manage the raptors. If you want grouse on the moors, you need to manage the trees. “They [SNH] go to Scandinavia and they say, we’ve got to have more trees in Scotland. Well why do we want to be like Scandinavia? We’re different than Scandinavia. Scandinavians come over here and think this is wonderful because they can see more than a hundred yards. We’ve got something that’s unique in the world, heather moorland. It’s rarer than Amazonian rainforest. And we want to plant it with trees to make it look like frigging Norway.”

It might be working in Yellowstone, he says, but Yellowstone isn’t Scotland. This is an artificial, peopled landscape, and that merits considerations which do not come to bear in the vast national parks of America. He tells me a story about the Isle of Skye, where a woman was sent out to address farmers’ concerns about the sea eagle taking lambs. “Someone said to her ‘this is ridiculous, it’s going to put us out of business, we’re just not going to be able to farm anymore.’ And the lassie said ‘maybe that’s the answer. Maybe you have to move out and just leave it for the eagles.’ Is it really that important we have eagles?”

It is easy to hear in this the narrative of the clearances. The principal characters may have changed, but the story feels familiar. Shifting those who belong there off the land for the benefit of outsiders. Justifying it through how it will make the land more economically beneficial. A final culmination of emptying the landscape, begun more than two hundred years previously. Certainly it is refreshing that we are coming to remember that other species have a worth alongside our own, but there may be something disturbing when they are placed on an equal footing.

“They’ve all got their woolly hat and their beard and they’ve all been to college and they’re all taught the same thing. That it’d be better if man didn’t exist on this planet. That we’ve got an adverse effect, we’re not part of the ecosystem, that we shouldn’t interfere with anything, and it’s absolute bollocks. We’ve as much right in this place as anybody else. Things have moved on far too far, for far too long. It’s going to cost some people millions. And it’s not gonna cost the people who think it’s a good idea a fucking penny.”

Those who depend upon the land for work would have their lives dramatically changed.

Three-quarters of Sutherland’s 5,200 square kilometres is in the hands of 81 families. One person is employed for every seven square kilometres. Sutherland generates £1.6 million through deer stalking annually, whilst £4.7 million is spent on deer management (Monbiot, 2013: 102). Those who own estates concede they are fantastic way to haemorrhage money: they are expensive playgrounds for the very rich, for inviting friends up for the occasional weekend of stalking and single malts. Surely there are better ways of managing the land than keeping it as a preserve for the shooting of deer and grouse, better ways of bringing in jobs and money. Maybe ways that involve bringing back large predators and tourists. Yet it is irrefutable that those who depend upon the land for work, not the absentee landlords but the few remaining locals, would have their lives dramatically changed. Maybe they could weather those changes, maybe in the long run they would be better off, but change is always significant and it is dishonest to pretend that things could just carry on as before. Whether curlews or red kites, whether gamekeepers or safari guides, whether forest or moor, whether grouse or wolves, these are difficult decisions and it is unclear who should make them. But they are being made all the time, and it is our responsibility to make them.

“In a country where you haven’t got a wilderness,” Allan says, “you have to play God.”

Next Week: Rewilding

Banner photo by Neil McIntosh ![]()