After leaving school at 13, he went from wanted criminal to best-loved poet, refusing an OBE, fighting institutional racism and working with Nelson Mandela. Now a university professor (and part-time Peaky Blinder), Benjamin Zephaniah is turning 60, publishing his autobiography and going on tour – and he’s as political and radical as ever.

“What do I do as a Black man in England? I try my best to counter the stereotype.

“For those people who fear Black men, I want to be the nicest guy they’ve ever met.”

Being a nice guy seems to come naturally to Benjamin Zephaniah.

Labelled Britain’s “people’s laureate” you may have seen him on Question Time, responding to xenophobia with tolerance. You may have read the stories he wrote to inspire troubled kids. You may even have heard this lifelong vegetarian advocating for turkeys at Christmas.

The Life and Rhymes of Benjamin Zephaniah will be released in May.

He’s polite. He’s prompt. And he’s political.

“Black men are seen as being always late,” he says, “being slightly off their heads and not being consistent. So I am always very much on time and very organised.

“That’s our responsibility as individuals because it’s very difficult to change years and years of brainwashing.”

Turning 60 this year, Zephaniah releases his autobiography in May, promising a social history of Britain, charting the struggle for racial equality interweaved with his own extraordinary story.

Winner of the BBC Young Playwright’s Award, featured in The Times’ top 50 post-War writers, and boasting 16 honorary degrees, Zephaniah left school at the age of 13, dyslexic and unable to read or write.

The son of a Bajan postman and a Jamaican nurse, he grew up in Handsworth, the heart of Birmingham’s African-Caribbean community, and when school rejected him he found acceptance in local gangs. He says:

When I got kicked out of school my teacher said I would end up dead or doing a life sentence. She said I was ‘a born failure’.

“It was the day I left school at 13 and I remember it clearly.

“You can be told you’re no good at something or you’ve messed up something, but to be told you’re a ‘born failure’, that you were nothing right from the start? My confidence went right down.

“But then when I was out with my gang and they’d say ‘Kick that boy’ and I’d kick him and they’d go ‘Yes, bruv!’. That was a way of getting my status.

“I was doing bad things with the boys. I wanted to fit in.”

Zephaniah got in trouble with the police, serving time for robbery in borstal and prison. He says:

I can remember the night I was lying in bed and I was sleeping with a gun under my pillow because somebody wanted to get me and I wanted to get him before he got me.

“I remember that night listening to Marvin Gaye – What’s Going On? And I remembered that teacher and I said, ‘I want to prove her wrong’.”

By 15, inspired by his local preacher, Zephaniah was reciting poems at punk gigs and gaining a following with his unique style.

He says: “I was performing in Handsworth when somebody said to me ‘You’ve got a real talent for words, you know? The world should hear you man!’

by Richard Ecclestone

“I thought, ‘What? People want to hear me? White people care about us?!’

“That sounds crazy now because there’s so many anti-racist movements out there but at the time, in Handsworth, it was a big shock that people wanted to hear my poetry.”

At the age of 22 he moved to London.

“When I tell kids about this,” he laughs, “I say guess what happened next? I got into another gang – a gang of painters and poets!

“We all need gangs. We’re social animals. The key is finding the people that are doing good stuff instead of doing bad stuff.

“I found these creative people in London and within two years I was on TV and I was being published.

I went from wanted criminal to best-selling writer.”

Zephaniah has used his platform to campaign for social justice and to advocate for disenfranchised people.

After the killing of 18-year-old southeast Londoner Stephen Lawrence in 1993, he supported Stephen’s family in their long and tireless campaign for justice, and became the poet-in-residence at the chambers of Michael Mansfield QC.

It was there that he wrote What Stephen Lawrence Has Taught Us, donating a handwritten copy to the British Library.

Ten years after Stephen’s death, Zephaniah’s aunty called the police asking for support with her son, Zephaniah’s cousin, Mikey Powell.

Factory worker Mikey, a 38-year-old father-of-three, had depression and was suffering a breakdown.

He died of asphyxiation in custody within 90 minutes of the police arriving, after they had run him over, sprayed him with CS gas, beaten him and refused to call an ambulance.

It took 10 years of campaigning for justice before Mikey’s family received an apology from the police for the “pain and suffering” caused to his loved ones, to which Zephaniah responded: “it is just an apology, and it is not justice.”

Now, approaching 60, Zephaniah still gets stopped by the police (before being recognised and waved on). He says:

I remember as a kid in Birmingham the police stopping me in the car saying: ‘Get out of the car, n****r. Where’s the weed?’

“I hadn’t even opened my mouth yet. The police would have to be a bit more sophisticated with their racism now than to just open the car and say that.

“They’ll usually feel their way and see who I am.”

Does he believe anything, in terms of personal or institutional racism, has improved over his lifetime?

“It’s quite easy to say ‘no’, and I can give you lots of examples of racist attacks on people in the streets and racist policing,” he says.

“But there are places in Birmingham and places in London where I couldn’t go as a teenager because of the National Front. And if I got beaten up by the National Front I could never go to the police about it because I would get beaten up by the police too.

“I’m not saying that wouldn’t happen now but it was happening on a daily basis to Black men before, and it wasn’t covered in the news. So in some ways things have improved.

“Even if I see a commercial where the product they’re selling has nothing to do with Black people but Black people are in it, I really notice that.

“And there are laws now. The Race Relations Act has been in place since the 60s.

“But changing people’s attitudes is a bit more difficult. Despite the laws, racism and discrimination still happen all the time at grass roots level and in terms of institutional racism there’s still a long way to go.

“If you look at certain institutions, like the BBC, or sports in general, lots of them have Black people in front of the camera but very few Black people behind the camera, making the decisions.

“In football we have loads of Black people representing the country, but behind the scenes very few. There are, what, three black managers in the Premier League? And two more in the other leagues all together?

It’s all right dancing in the club but who owns the club? Who’s playing the tunes?”

Since last year’s fire, Zephaniah has been vocal about the treatment of the residents of Grenfell, praising the community’s emergency response as “anarchy in action” and calling out the media for token multiculturalism.

He says: “We have a media and a government that doesn’t celebrate multiculturalism enough. They only look at the Black people and the Muslims they approve of.

He says: “We have a media and a government that doesn’t celebrate multiculturalism enough. They only look at the Black people and the Muslims they approve of.

“When I was growing up the only time we saw Black people on TV was for crime .

“I remember getting a film script where I was at a door selling drugs to somebody so I asked the producer ‘Can you send me the rest of the script so I can see the context of this?’ and I never heard from them again.” He adds: “The film was a flop.

“Look what happened with the guy driving a truck into [Finsbury Park] mosque. Look at his background.

“It’s not just that he hated Muslims, it’s that he hated Black people, gays, Jews. He thought women should have a particular place in the world.

He was a true modern day Nazi, reading Hitler. This is a young man living in Britain now – and he’s not the only one. How do we stop these people?

“We have to understand the whole history of colonialization, where the British and some other European countries have gone out and colonised people and places.

“They called Africa ‘the dark continent’. Prejudice is deep in the language.

“There’s a grave of a slave in Bristol where the slave owner, who was seen as being quite liberal in the day, allowed his slave to have a Christian burial.

“But you read the gravestone and it doesn’t say he goes to heaven as a Black man. It says he goes to the gates of heaven and is then painted white before he’s let in.

All the books have to change. The way we educate has to change.

by Richard Ecclestone

“Black people are not slaves. They are human beings who were turned into slaves.

“Before slavery there were universities in Timbuktu and Alexandria. I show this to young people and they’re amazed.

“The first air conditioning systems and drainage systems to take waste away from homes came from Egypt. These seem like minor things but they challenge the idea that this version of civilisation is the only one.

“And it’s not like this is all about history. Whatever one thinks of the Royal Family, their family has been part of it.

“There are jewels in the crown that were stolen. There are things in the vaults of Buckingham Palace and in our British museums that were stolen and I think that’s what they are scared of: some stuff has to be given back.”

In 2003, Zephaniah was “horrified” to receive the offer of an OBE not long after Tony Blair’s “Cool Britannia” campaign.

Only two years before, in his anthology Too Black Too Strong, the poem Bought and Sold had plainly conveyed his disdain for royal honours, so he used the invitation to again voice his opposition to the monarchy and the continuing ethos of the Empire.

Refusing even to conform to a single career, Zephaniah flits between teaching and writing poetry, books and music (as well as acting in Peaky Blinders).

He became the first person after Bob Marley’s death to record with The Wailers – a tribute song to Nelson Mandela which started a long friendship between the two men, united in the fight to end apartheid.

Now, at least on the surface, Zephaniah’s life looks relatively conservative.

Living for the past six years in rural Lincolnshire, he grows his own vegetables and listens to Gardeners’ Question Time.

He’s an honorary patron of The Vegan Society and a professor of poetry at Brunel University.

But Prof Zephaniah remains dissatisfied with preaching to the converted, continuing his mission to convey complex ideas with simplicity and to take an archaic, inaccessible and predominantly white art form, and make it real and relevant to everyone.

He says: “I remember hearing about Enoch Powell and thinking ‘If he’s so clever why is he a racist?’

“You put that sentiment into poetry and people go ‘Yeah man! It’s that simple! It makes sense!’

“Even doing interviews I struggle for the words, but when I’m doing poetry I have this licence. I can change the words, leave a bit to your imagination, I can be as raw as I want to be.

“My mom always says when I’m on stage ‘That’s when I see my son’. It’s not the other way around.

“I’m acting when I’m off stage, when I’m talking to people and trying to be a normal person!”

The Life and Rhymes of Benjamin Zephaniah, will be published by Simon and Schuster on 3 May, and he will be touring 19 towns and cities in May and June.

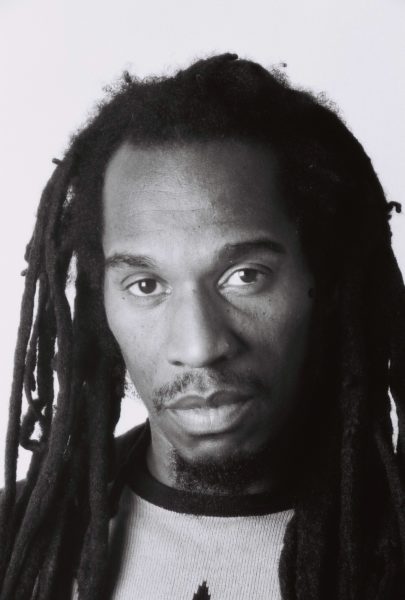

Main image by Adrian Pope.

- For more stories like this follow us on Facebook or subscribe here.

Benjamin Zephaniah: “The last thing to make me cry was an act of war”