After spending many years sleeping rough, Bekki Perriman has created a gallery of doorways to share the untold stories of Britain’s homeless women.

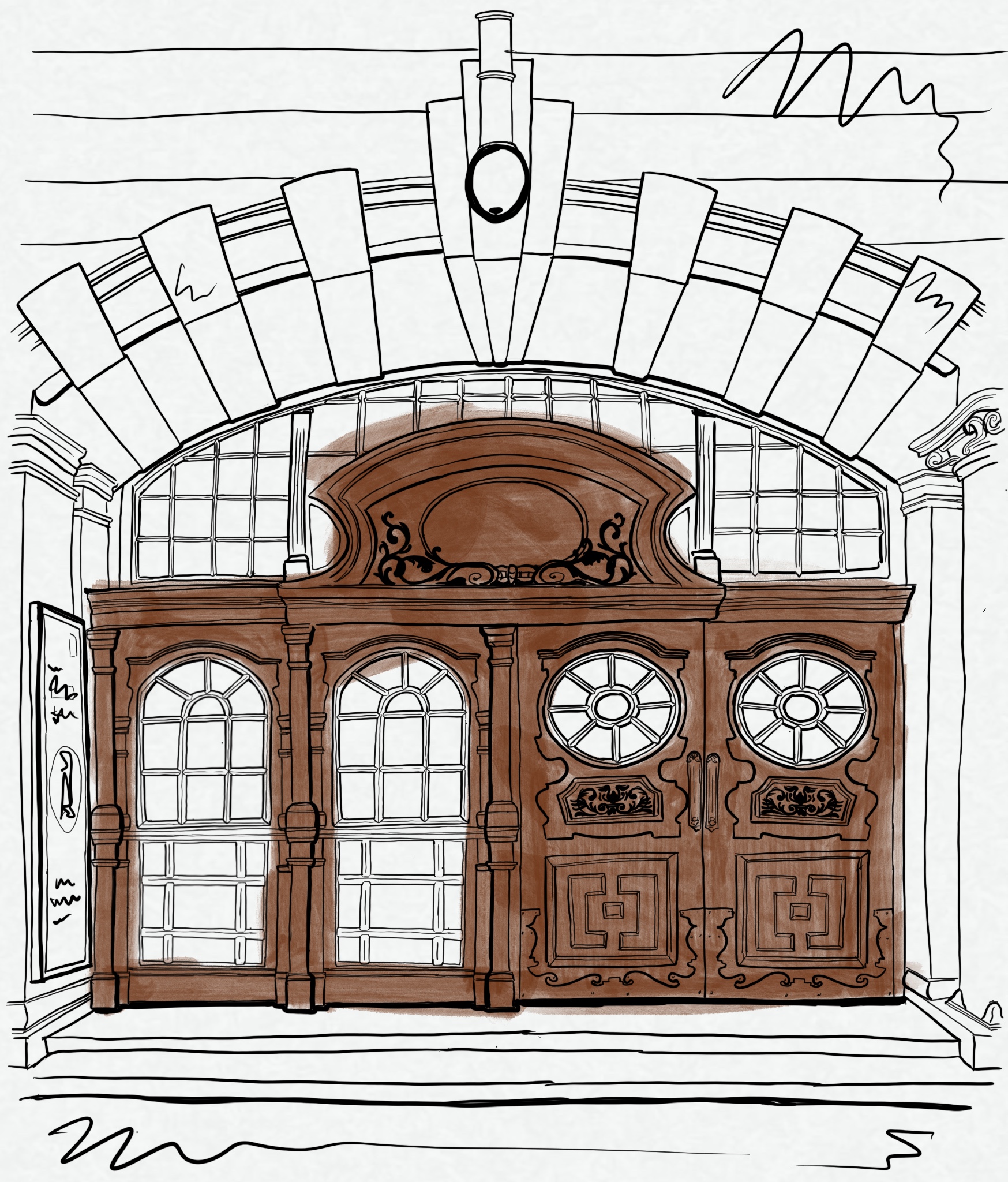

In her new book, Doorways, Perriman offers rare insight into one of society’s most marginalised groups by sharing brief testimonies of her times on the streets alongside the doorways she slept in.

Below we are featuring a selection of the images, followed by an interview in which Perriman shares the challenges of being a woman experiencing homelessness.

Veronique Mistaen speaks with Bekki Perriman about Doorways

“It’s like you’re a piece of dirt. People walk past you and tell you to ‘get a job’.

“Being a woman, you are so vulnerable to men, who think that just because you’re homeless you’ll do anything for a couple of quid,” says Bekki Perriman, talking about her long, hard years sleeping rough.

We sit in the courtyard of London’s British Library sipping coffee and lemon juice, discussing her book Doorways: Women, Homelessness, Trauma and Resistance, recently published by House Sparrow Press. Perriman, an artist and writer who works on issues of mental health and social exclusion, tucks her long chestnut hair behind her ears and speaks softly, hesitantly. It is hard for her to revisit her years on the streets.

“It’s like all the rawness and pain from the streets have come flooding back and it’s hard to process,” says Perriman, 40.

She chose to write Doorways to tell the story of homeless women – a story that is rarely understood unless people have been homeless themselves.

“People might speculate on why someone might end up homeless – mental health issues, substance misuse, debt, abuse, relationship breakdown – but very few people understand the day-to-day experience of being homeless.”

The book offers a rare insight into one of society’s most marginalised groups – through Perriman’s photography, memories and interviews with homeless women. These sit alongside essays by academics, artists and activists, exploring the cultural, social and political dimensions of women and homelessness.

The idea for Doorways emerged when Perriman was wandering through the West End a couple of years ago. She knew the place inside out because the streets, the side alleys, the doorways were her home for many years. Each holds memories of repeated trauma, but also of resistance and resilience.

It hit me that people walking by saw only a doorway, a place tucked away, but had no idea that people used to sleep there. That people still live there.”

She began photographing the doorways where she used to sleep “as a way of expressing the invisibility and horror of homelessness, but also as a way of telling stories of friendship and everyday life.”

As an extension to her photography, she recorded short interviews with homeless people and the project developed into a book.

On any given night, about 4,750 people are sleeping rough in England – a 250% increase since 2010. At least 14% of them are women, but the number could be far higher as many women are “hidden homeless,” hiding away out of shame and fear of sexual assaults and violence. Several of Perriman’s friends died on the streets.

There are complex reasons why women find themselves on the streets. Most have experienced multiple trauma and abuse both before and during homelessness. Yet, very few homeless services are gender specific and equipped to deal with women’s multiple disadvantages and needs.

For her Doorways project, Perriman interviewed 17 people and selected testimonies from eight women for her book. She uses the women’s first names only and doesn’t tell us their background, age nor where they live to protect them from the stigma associated with homelessness and because their families might not know the extent of their situation. She was equally protective of her own background. All she would say was that the women were aged from 22 to late 50s and from Glasgow, London, Brighton and Liverpool. Every single one had difficulty accessing housing support and many described being passed on from one agency to another and back again with no one willing to take responsibility.

One of the women quoted in the book, Emma, explains: “I tried to get help. I went to this advice centre nearly every day and they kept telling me the same thing: everything is full. They tell me to try Women’s Aid, but Women’s Aid tell me to try the advice centre and it’s just going around in a circle… It’s been almost a year now and I am still sleeping rough, they still haven’t found me anything.”

Jessica, another woman interviewed, says the Homeless Persons Unit wouldn’t help her because she was not considered “priority need”. “But I don’t know how much more vulnerable I could have been. I had nowhere to go at all. The ironic thing is that, although the council were telling me I was ‘not a priority’, a lot of hostels and night shelters were saying I couldn’t have a bed there, as my ‘support needs were too high’.”

Many shelters have no women-only areas. If they do, they might be separated from the men’s by a piece of cardboard or can only be accessed by crossing the men’s section, Perriman says.

“It’s not a safe place for someone who has been abused. I remember going to a night shelter. I had my own space, but it was separated from the men’s area by a glass window and they were all looking at me. I didn’t last 10 minutes. And emergency shelters have 20 or 30 people sleeping on the floor with all their various problems. That’s why homeless people don’t want to go there.”

The streets sometimes feel safer for homeless women as they can find friendship and a deep sense of loyalty and community, but it’s nonetheless the most brutal, crushing environment.

“Everyone is trying to survive,” says Perriman. “Then there is the constant abuse. Every single day someone abuses you, makes nasty comments about you, urinates on you and might sexually assault you, just because you are homeless. It is so hard to cope.”

National charity for homeless people, Crisis, found that people sleeping on the street are 17 times more likely to be abused than the general public – and in most cases the perpetrator is a complete stranger.

“Drunk people thinking it’s ok to use me as a bathroom, I hated that, and I was sleeping with one eye open,” says Arna, another woman quoted in the book.

“I often sit by myself now just reading and ignoring people. That is the only way I can cope, putting my head down into a book and just ignoring everybody that goes by me. I feel invisible,” Susan says.

It is for Arna, Emma, Jessica, Susan and all the women sleeping rough that Perriman wanted to write her book – “to help humanise a situation that many people find threatening or uncomfortable. Perhaps people may be a bit kinder or have more compassion towards the homeless people they walk past.”

- Doorways: Women, Homelessness, Trauma and Resistance By Bekki Perriman is published by House Sparrow Press and can be bought here.

All sketches by Kassidy Dawn.