Almost two years after the EU bailout of Spain, the Euro crisis is still very present in the everyday lives of young Spaniards. Youth unemployment hovers around 60%, and the desire for political change remains unsatisfied. The Euro crisis has instilled in Spain’s youth an awareness of their lack of prospects, coupled with a cynicism towards domestic affairs. There is a generation of young skilled people whose main objective has become to flee the country.

Among Spanish university graduates there is a stark awareness of the lack of prospects. “We are the generación perdida – the lost generation,” says Raquel, a 26-year-old audio-visual communications graduate who has been looking for a job since her graduation in June 2013. When asked what kinds of jobs she is seeking, she says anything will do. Unable to find a job which builds on her communications degree, she is searching for jobs as a waitress. “Out of our classmates I only know one with a paid, degree-related job. Others are either working without pay, doing stints in restaurants or shops, or unemployed,” she continues.

Miguel, a recent architecture graduate, says that he and his girlfriend sent 40-50 job applications each upon graduation, without a single response. In the end, the pair had to migrate to Madrid from their home town, one to work as till staff in a retail store, the other having obtained a temporary degree-related job through a family connection. These youngsters realise that if they cannot find a job that matches their degree, they will be left without specialised work experience. And they worry that when the economic situation improves, there will then be new a generation of graduates, more attractive to employers due to their more recent university education.

What are the options for these young people? Hundreds of thousands of young Spaniards are moving to work abroad according to Deutsche Welle, and even more would go if their language skills allowed it. In 2011, the media picked up on a European Commission report about youth mobility entitled Youth on the move. It found that almost 70% of Spanish young people want to find work in another European country, triggering headlines such as “Unemployed youth turn their backs on Spain”. When compared with figures in other countries, however, the situation perhaps seems less extreme – Spain’s 68% is overshadowed by rates of well over 70% in the Nordic countries, and is only ten percentage points above the desire of British young people to move abroad.

Spanish youngsters seem to want to go because they have to go, rather than because they want to go.

Yet in Spain the talk of leaving has a darker tone. When asking Spanish students and recent graduates about their future plans, moving abroad comes up almost without exception. And Spanish youngsters seem to want to go because they have to go, rather than because they want to go. A group of 19-year-old international relations undergraduates, Laura, Carmen and Alejandro identify several people in their close circle who have had to leave the country in search of a job, mainly to Germany, Britain, or South America. “Define have to, though. It’s not like they’d die of starvation if they stayed,” challenges one. A response comes from his peer: “Alright, one can stay in Spain, but at what cost? Having to depend on your parents till you’re 30?” The group concludes that for them, the most important reason to leave would be to find a job that matches their education.

Some would argue that the Youth on the move poll represents a lot of talk but no action: “Many say that they want to go, but then don’t do anything about it,” says Adriano, a 24-year-old maths undergraduate. But statistics tell a different tale. The European job seekers’ portal Eures has more Spanish job seekers listed than those of any other nationality except for Italians. The urgency to emigrate is also demonstrated in the high demand for foreign language classes, especially English and German. Raquel is now on an English course hoping to find work abroad, and the demand for private classes and language exchanges appears never-ending. “There is never a situation where I want to take on another student, but can’t find one,” says Joseph, an English teacher giving private classes mainly to young graduates.

The youngsters’ plight also translates into a deep distrust in government and politicians. The Spanish political system is effectively a bi-party one, with the Spanish Socialist Worker’s Party (PSOE) and the centre-right People’s Party (PP) have alternated as governing parties since the 1990s. Having emerged from a dictatorship in the 1970s, Spain is still a young democracy in Western European terms, which shows in its political practices.

“I personally don’t know anybody in favour of the government anymore – not even among those who still supported the governing parties five or six years ago. Government malpractice is so evident that it is impossible to overlook,” says Juanma, a 25-year-old economics student. This view is supported by a 2012 Transparency International report on corruption in Europe . It concludes that the public administration in Spain is “found seriously wanting in terms of the legal framework of accountability and integrity mechanisms, and its implementation in practice. […] inefficiency, malpractice and corruption are neither sufficiently controlled nor sanctioned.” Spain appears to be a prime example of a classic pattern: whereas malpractice is ever-present behind the scenes, it is only exposed to the public eye in times of economic downturn and increasing public demands from the government.

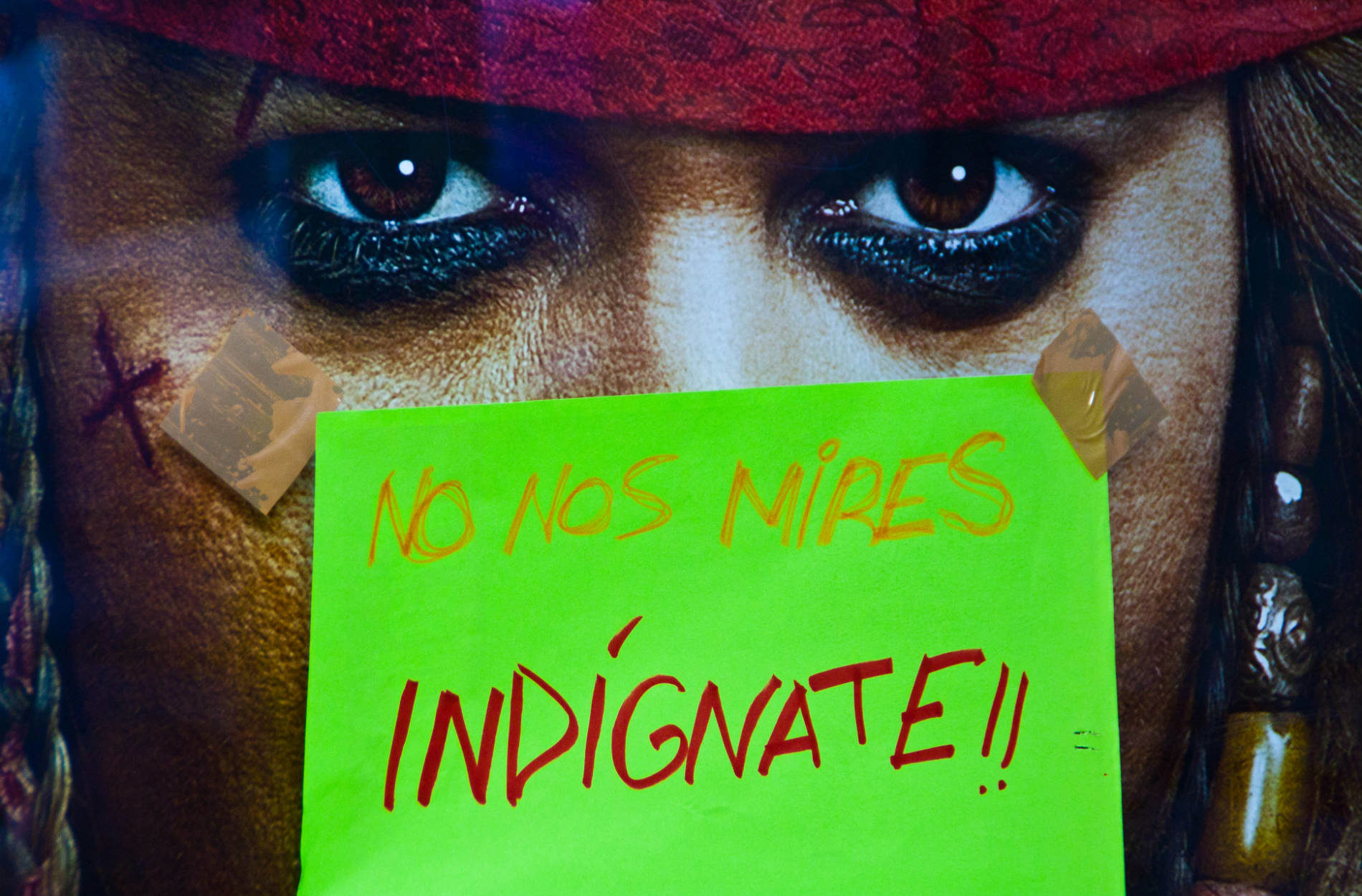

Laura, Carmen and Alejandro shed light on the motives for discontent, complaining that “the government only concerns itself with the interests of the wealthy. Something we don’t understand, for instance, that they claim not to have money for healthcare or universities, but somehow funds are found for a new motorway.” Miguel continues in the same vein: “When I hear the word politician, it is like hearing the word pirate.” To him it seems like the government is not interested in the people and tries to divert attention from important problems. “It is a very disconcerting thought that the people who should be taking care of you don’t do that,” he says.

“When I hear the word politician, it is like hearing the word pirate.”

Government malpractice, however, is met with increasing passivity. The 15M movement that lists lower unemployment, fewer privileges to the political class, and invigoration of citizens’ rights among its objectives started as a sit-in on Madrid’s Plaza del Sol on May 15th, just before the last parliamentary elections almost three years ago. Demonstrations quickly spread to other cities and towns, and up to 80% of Spaniards said they supported the movement in the summer of 2011. A study conducted by El País in May 2013 found that the support for the movement’s aims has not fallen significantly, with 69% of young people still standing behind the movement.

Yet to most of the students and graduates interviewed, the countermovement appears to have lost steam. “I think it’s because people see that they haven’t actually achieved anything. For example, university fees are still rising and grants are being cut, for, and corruption scandals are on the news every other day,” says 19-year-old Yanilda. In addition to the lack of tangible results, the movement has been hindered by increasing regulation: “The authorities have made it more difficult to protest. Nowadays they give fines to people for camping outside among other things.” Amnesty International came to a similar conclusion in a report in April, stating that the Spanish authorities have responded to the mobilisation generated by movements like the 15M with “unnecessary or excessive use of force during demonstrations, the fining of organisers and participants and legislative proposals imposing additional restrictions on the freedom of assembly.”

Juanma on the other hand perceives that frustration has pushed the movement in a more radical direction, away from the popular, peaceful movement that it was to start with. And indeed, in the protests against another tightening of the university grant application process, out of the 53 people detained only half were students – the other half were members of extreme left-wing groups. This radicalisation makes it more difficult for a broader audience to identify with the ongoing political activism.

The economic crisis and the increased cynicism towards domestic politics also shape perceptions of the European Union and the Euro. The 19-year-old Laura, Carmen and Alejandro believe that the leaders of the EU are replicating the behaviour of their own government. “I think the EU is unfair, acting in some people’s interest and overriding or ignoring those of others. They mainly only work in the interest of German banks – you can really see the influence of Germany. Not enough has been done to help Spain,” says Carmen. These three share the sentiment of Yanilda, to whom European integration is “a good idea that isn’t working in practice”.

On the other hand, the increased opportunities brought by the union are welcomed with open arms. Not surprisingly, freedom of movement and programs such as the Erasmus exchange are viewed as great benefits to students and graduates across the board. To some, the EU is seen as a counterforce to the corrupt Spanish government: “The more power we give to an outside organisation, the better,” says Juanma, who is in favour of a fiscal union. “Given proper institutional frameworks and incentives, tighter integration can only be beneficial to Spain.” All the other youngsters interviewed welcome European collaboration – as long as it is fair.

The economic situation has left an indelible mark on the attitudes and outlooks of Spanish youth. Their lack of future prospects is reflected in their widespread pessimism about national politics. And as trust in domestic affairs falters, European cooperation and mobility seems like the best way out of the crisis to most, whether it be on a personal, or on a national level. “Just don’t leave us alone in our troubles,” pleads 19-year-old Sharon.

Photo by Pablo AL