Yesterday was the first anniversary of his death. He would have been 41 years old this October. Unlike ‘love,’ which seems to imply a viscosity of feeling wherever it is applied, ‘loss’ is a vacuous term, describing even trivial occurrences that do not seem to warrant its use. I could lose a pencil but it’s not like losing him.

He had been disabled since the age of three – diagnosed with a spinal tumour that made him no stranger to hospitals and surgeries. This did not prevent him from graduating from the premier law institute in India – the National Law School of India University (NLSIU) in Bangalore. He specialised in copyright law, and started running his own firm in Chennai. In his 30s, he underwent a risky surgery that deprived him of partial mobility in his legs.

In 2008, he was invited by the World Blind Union to help draft an international treaty on providing material in accessible formats for the print-impaired. While he was sitting there trying to control the periodic spasms in his leg so that he didn’t shake the table too much and spill his coffee, it dawned on him that he too was a member of the disabled community, a community which had its own specific requirements. It was perhaps then, at that very moment, that his life forked across two distinct terrains: either continue as an intellectual property rights lawyer or change his specialty entirely, enter a new field of law and fight to protect, preserve and promote the basic rights of the disabled. He chose the path less trodden.

Once, when he was young, he and his classmate were pulled up in class because their answers for an examination were exactly the same. To find out who had copied who, they were both made to answer a question on a blank sheet of paper. ‘I didn’t copy,’ wrote his classmate, while he wrote, ‘Me neither.’

Many years later, I had started working as a reporter for a magazine called The Week in India. I called him for help on a story I was writing about there being too much copying and not enough innovation in the Indian entertainment industry.

‘Have you ever thought about what’s wrong with copying?’ he asked me. ‘It’s actually copyright law which prevents the disabled, specifically the visually-impaired, from accessing content and converting it into formats like Braille, audio or e-text. But it’s not only the blind who need different formats. Copyright law stops that. Or makes it harder and more expensive.’

Thus was born the idea of ‘Inclusive Planet’ – an organisation that works on all aspects of disability rights – from reform in copyright law, creating a social media platform for the visually impaired (that is now the largest social network in the world for the disabled) to organising campaigns to provide people with visual disabilities the right to read.

What is my relation with him? He was my first cousin. To me, he was always the ‘cool dude’ of the family – the one who tattooed the logo of his company on his forearm; the one who wore a custom-made kurta at his own wedding with a feather nodding at you from the back; the one who created a ‘pyramid’ of his family’s good looks and placed himself at the pinnacle.

He had always been a rebel, even before he found his cause. He could make you believe that prostitutes enjoy sex, that God is a farce and that MBAs are for sissies. (The moment you agreed with him he would take the opposing view.)

I don’t know whether he believed half of what he said. In many ways he was a chimera, or a shape-shifter. Trying to pin him down was like trying to fork a grape on a buttered plate. The lawyer in him could convince you that artificial intelligence would rule the world in less than ten years. He could cite quantum physics, Moore’s law, power sources, censors and target environments to prove his point.

There is often a thin line between the acceptable and the offensive. Often, he tangoed with that line. He could nettle you, provoke you and leave you dumbfounded. He could question every belief that you stood for and sometimes strip you of them entirely. If it had been anyone else, you would have run a truck over him in your mind many times over. But not him. The conviction that you are unique is ubiquitous but it is not often that the conviction that someone else is unique is unanimous.

In his fight for justice for the disabled, he did not paddle. He dived in. He organised the Right to Read campaign which ultimately led to an amendment of Indian copyright law. However, at this point, he started wondering if he could really make a difference in the world. Should he have continued as a copyright lawyer?

Perhaps it is fate which brought him an email from a person in Turkey with visual impairment who used Inclusive Planet to access books and other reading material online. The person asked him if he could translate the website into Turkish as there were many blind people in Turkey and ‘to benefit from this treasure is their right too.’ The email set the course of his life. There was no turning back.

Occasionally, he would ping me on Facebook asking if I had read his latest article in some magazine or newspaper. It was not out of vanity but simply a desire to share his passion with others. Once I told him that perhaps in ten years, if we were lucky, we might have a Nobel Prize winner in the family. ‘Ten years?’ he asked. ‘You’ll have one in three.’

He was on the panel of legal experts constituted by the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment to give input on India’s new disability law. He had helped the State of Kerala to draft a plan document with a vision to ensure that by the year 2025, persons with disabilities shall be completely integrated into mainstream society. He was one of the experts who helped to draft the international Treaty for the Visually Impaired, and was subsequently invited to assisting the World Blind Union, advocating for the treaty at the World Intellectual Property Organization.

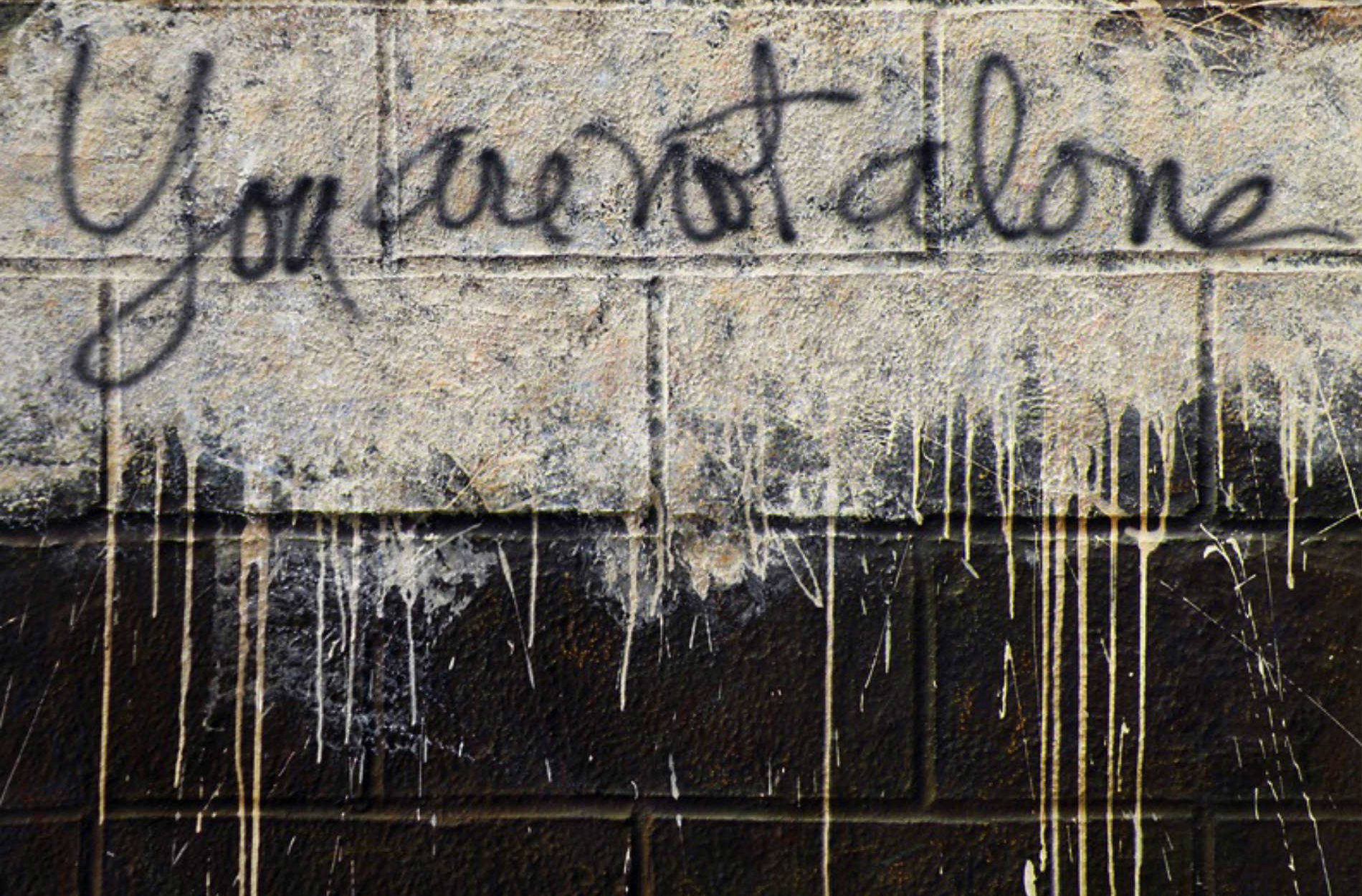

In February 2013, he contracted an infection while on a family vacation to Goa that left him in intensive care for many days before he left us. But his legacy remains, summed up by the logo of his company tattooed on his arm: an alien with crutches pointing at you and saying – You Are Not Alone. The tattoo was just one way in which he lived his ideals.

I’ve realized that other people’s opinion of you does not rest on your accomplishments, or who you are but how you make them feel. He was special because he made us all feel special. Each of us fancied that we were his favourite person in the world, not knowing just how many of us there were.

Some weeks after I had finished my journalism course, he asked me if I’d like to do some pro bono work for him. I looked at him, abashed that I didn’t know the meaning of the word ‘pro bono’ despite graduating from a journalism school.

‘Free of charge,’ he told me gently, and I agreed.

Sometimes, the relationships that come free of charge are the ones that cost you the most.

Rahul Cherian died in February 2013 aged only 39. The organisation he helped establish, Inclusive Planet, continues to campaign for the rights of persons with disabilities in India.