Two adolescent boys withdraw from school life and enter into the murky world of scrapping, roaming the dour West Yorkshire landscape in search of metal to trade for sustenance. A stylish film from Clio Barnard, whose reworking of Oscar Wilde’s short story opens up the debate on socioeconomics and the darkest mores of contemporary capitalism.

School uniform is a great leveller, concealing beneath its colour-coded livery the disparate lives of its wearers. By which I mean only that starched collars, pressed trousers and buffed shoes tell but part of a story that begins well before eight-thirty and continues well after three.

I worked for a time in a Nottingham secondary school, the lie of its catchment meaning that it took in pupils from some of the city’s most deprived wards. Perhaps partly as a result of this – its large numbers of children whose families hovered somewhere near the breadline – its prescribed school uniform was somewhat unambitious: only crested yellow polo shirts and plain black trousers were mandatory. Even still, by the spring term some yellow shirts appeared visibly murkier than others, some trousers bore marks and frayed edges where others remain pressed and jet-black.

There is something deeply saddening for any teacher about the sight of a child whose muddy-kneed trousers remain in a smudge-brown state for days at a time, perhaps even spanning a weekend; something quietly troubling about the child with ever-dirty fingernails; or the one who admits to never having eaten breakfast. I am not being elegiac here, not trying to raise eyebrows by painting greyscale portraits of lives less desirable. There exists a sizeable (and incontrovertible) cohort of the school-age population in Britain who are overwhelmingly regarded within schools as problems-to-be-solved. Children who for one reason or another have been failed somewhere along the way – by any combination of dubious parenting, poor governmental decision-making or just plain bad luck – and who, consequently, often become treated as hurdles in the way of others’ learning. I would query the testimony of any teacher who claimed never to have sighed relief at the absence of a problem child from a classroom on a given day.

These children can be, more often than not (although I write only anecdotally here), the offspring of parents whom wider society has treated with a similar predisposition. I am thinking of the sorts whom we – and I use plural with a degree of confidence – have been at one point or another quick to judge, to scoff at, on the narrow basis of appearance and elocution before all else. A Jeremy Kyle generation, as the very least sympathetic have put it, a tracksuit-wearing underclass of chavs, scruffs and benefit cheats.

Part of the problem has been that over the course of the last decades, and particularly since the 1970s, we have begun to lack an adequate vocabulary with which to discuss class, instead falling back on an uncaring, reductive nomenclature that casts the wealthiest among us invariably as unscrupulous money-grabbers and the most disadvantaged as shirkers and scroungers. It does not nearly do justice to the reality. The discovery of a suitable vocabulary then is paramount, especially for use as a tool with which to overturn a perverse logic that sees deprivation as a metonym for bad taste, ill manners and indolence. As though anyone a step above the lowest rung of the social ladder could turn up his or her nose.

Equally pressing, too, is a need for writers and artists to discover a sensitive and suitable language – read: antithetical to the sort of practice that has held up, say, Vicky Pollard as a grotesquely caricatured, cultural figurehead for the deprived – a language that may speak of social deprivation in a productive, and hopefully revolutionising, way.

What is written here comes directly off the back of watching The Selfish Giant, as though it were a segue to deep, topical discussion. Yet Clio Barnard’s film is not overtly political, makes few sloganeering advances on the viewer, and yields little hardened context from which we might draw judgement. That is its strength, though, that it speaks of the plight of two young boys roaming around in a lost time.

Nevertheless, when the film opens and introduces the two leads, Arbor and Swifty (Conner Chapman and Shaun Thomas), all ‘bell end’ this and ‘daft twat’ that, one could be forgiven for seeing them in the same mould as Billy Casper (Kes) or Shaun Fields (This is England), cheeky tearaways to whom we can latch onto as teenage anti-heroes. Unruly types whom we can cheer on in these sorts of callous landscapes, whilst wilfully forgetting that they would be the first ones we would shoo from our streets in real-life.

But there is something altogether too resonant about these two, even when they enter into the unfamiliar arena of metal scrapping. I watch the film with a teacher; I know exactly that child, she says of both Arbor and Swifty in the early stages, when the boys are still in school. Arbor is the archetypal baby-faced imp-child, likely to dish out expletives with an angelic grin; Swifty is the one who tags along because it provides him a friend he might not otherwise have. They are the types likely to exhaust and endear teachers in equal measure, but kids whose antics have their roots in unenviable home lives. And they do here: Arbor is fatherless, while his brother is drug-dependent and reckless; Swifty is the oldest of seemingly countless siblings, and the son of a father who is squirting away the family’s meagre income.

In partnership, the two boys have a dynamic remarkably similar to that made famous by Steinbeck’s George and Lennie: the little and large duo alone against the world, with no more than shared dreams of financial security to their name.

Indeed, solvency is the biggest morsel the film encourages us to chew. When the boys are excluded from school after fighting, their subsequent scavenging brings in much needed income for their families. When Swifty’s mother talks to him, preaching the value of his education, we have already seen his father selling an as yet unpaid-for sofa for a knockdown price and his numerous siblings eating cold beans from plates on their laps. What immediate value can education have if it cannot put a square meal on the table? The half-heartedness of the mother’s preaching suggests she thinks likewise. (It is, incidentally, a figurative table – there is not one to be seen in the household.)

The inclusion of the school setting is integral to the success of the film, though. Its clean lines and polished floors are at odds with the damp, cluttered scrapyard where the boys, to a degree, find much more joy. But the school remains perpetually as the anchor from which they have drifted. The conversation between head teacher and parent (‘I’m sorry, I don’t think mainstream education is an option anymore,’ the former says) is a vital reminder of where the boys should be spending their days. They are not ready-made trickster figures always destined for scrapping, but would-be school children who have lost their way.

Whether we put it down to good casting, scriptwriting or just good chemistry, the on-screen performances of Arbor and Swifty are pitch-perfect. Not only do they feel like knowable figures, they epitomise an endearingly innocent attitude to money that has at one time gripped the best of us (‘Sick! I can go out scrapping and earn some money,’ Arbor titters at his exclusion.) But where I might have half-wished at thirteen to forego education and favour employment instead, the boys actually follow through with it and for a while reap rewards that are indispensable to their families. Perhaps getting caught up in the fantasy of the plot, I do not wish for the Arbor and Swifty to return to school, but hope instead that they continue to steal and scavenge their way through life. Why? Because it feels like the most viable option for them.

They quickly evolve from school kids into legitimate agents in the scrap scene. They begin to appear ageless. What does age matter, I think, when the value of money is not graded relative to it? By the end, to hear Arbor asking adult-like at the scrapyard for the receipt for his traded wares does not, like it does the first time, draw a laugh from me; it just seems like sound business sense. There’s a good lad – keep hold of a record, just in case.

As much as the film is a commentary on social deprivation, it is a direct address to the terminal conditions of post-industrial capitalism. Or, put in less grandiose terms, it shows us what happens when one is driven to trading in an attempt at mere survival.

Social realism has provided fertile ground for British filmmakers for half a century or more, from Ken Loach through to the likes of Shane Meadows and Samantha Morton in recent years, and The Selfish Giant undoubtedly emerges from the same tradition. Just as the boys might be archetypes of the genre, the depressingly blue-tinged filtering of the cinematography, making every scene look like it has been filmed at dusk, feels like a staple inclusion.

The landscape of post-industry has in some ways been reduced of late merely to an aesthetic, a distinctive look that sometimes seems to have shed the sorrowful story of its decline. (And not only on screen. How often one nowadays encounters, say, restaurants whose décor of bare brickwork, exposed pipes and obsolete industrial curios testify to the vogue of this befallen era.) One might be forgiven for thinking that canvas backdrops featuring the looming silhouettes of cooling towers and dilapidated shopping precincts have been passed from filmmaker to filmmaker in recent times, each one unfurling it at a convenient point in their respective productions to emphasise a number of points: This is the nadir of post-industrial Britain. It’s fucking awful. But doesn’t it look somehow dour and yet beautiful all at once?

Here, though (and again it is a cap doffed to Barnard), the furniture of the film is put to constant use. Buzzing, popping power lines are not in shot for show, as they often seem to be, but are invested with a money value (which the boys soon cotton on to, considering stripping the rubber off and trading in the metal cable). In fact, everything in shot appears to advertise its value, and I find myself gradually drawn into the boys’ way of thinking, looking constantly for anything that might have a monetary worth. Everything holds the potential for profit, no matter how meagre. I don’t recall ever watching a film in this manner – pick that up, I want to blurt at the screen, that’ll be worth a few quid – and certainly do not remember a mise-en-scene that seems to speak so resonantly of the world it seeks to portray. At one point I notice something as simple as a half-drunken bottle of cheap squash on the kitchen worktop in Arbor’s kitchen and suddenly it fills my head with ideas about the kind of lives the film is dealing with. It is a subtle signpost (barely one at all, in fact), and one much less pigeonholing than tracksuits and broken televisions discarded in front gardens. It might have just been happenstance, a happy accident, but it is so effective. It takes me back to a previous point. There is little sloganeering in the film, none of the more obvious cues that would both alert the viewer to this as an arena of deprivation but also, in that very instant, put it beyond the reach of our action.

A film that rests too heavily upon an aesthetic risks elevation to the solitary status of artwork. That does not appear to be Barnard’s aim. In line with the film’s spirit of thrift, the director leaves not a scrap to surplus: there is no musical score, virtually no computer graphics and the dialogue is astonishingly economical. It inhabits a sense of austerity as much as it imparts it.

I wrote earlier of the need for a revolutionary language with which to revive platforms of representation for this marginalised cohort. Naïve would be the artist or writer who felt this undertaking was within their grasp alone.

Such a feat, as Owen Jones has written, requires not that we tackle prejudice itself, but the fountain from which it springs. And yet we should not underestimate the worth of artists, least of all Barnard, who hits upon a language that feels unremarkable and yet on the money enough to help get to the heart of the issue.

In a literal sense, the language of The Selfish Giant – and I am not intentionally indulging in the hyperbolic here – is about as progressive as I have ever seen on film. Shane Meadows is rightly praised for the naturalistic, off-the-cuff dialogue of This is England, but Arbor and Swifty’s seemingly improvised conversations here are so organic and candid that they need never spell out anything explicitly at all. Arbor’s diction is stilted, punctuated with the great sighs and screwed-up facial expressions one might expect of a moody teen (‘I work my arse off, yeh,’ he says to his mum, ‘for this [money], for you, yeh. And you don’t even accept it, you ungrateful bastard! Fuck off!’).

Swifty’s deeper voice is that little bit slower, with an ever-rising intonation that always borders on disbelief, his pronunciation invariably suspect (fick, he says, instead of thick). Vitally, though, when the film’s central trope crops up – money, the lack thereof, its wider implications – the characters’ dialogue always speaks so rudimentarily to it that, paradoxically, it resonates much more powerfully than if their inner thoughts were laid bare. We are poor, they might well say, being failed somewhere along the line; we lack suitable role models, opportunities, support systems. Instead, dividing out their winnings at the scrapyard (after trading in a stolen cable drum), the boys’ conversation runs simply as follows: ‘Swifty, ‘undred and ten quid there. That’s mum’s electric, that.’ ‘Ha, buzzin’!’ ‘What you gonna spend yours on, then? Buy a new settee and that?’ ‘Yeh, ha!’ Pause. ‘‘Ere’ though Swifty, just don’t let your dad get ‘is ‘ands on it.’ ‘No, I wont.’And all this in a dialect that, perhaps coincidentally, lends itself so well to this sort of banal exchange: a wonderfully thick, seesawing Yorkshire lilt.

The film is about much more than Arbor and Swifty, and there are some impressive cameos along the way, a leitmotif of horses, too, that might sustain a piece of writing by itself. But I am drawn always to the two boys because, watching the film, I am swept up in a wave of naivety much like they are. I, too, feel for a while like there is a happy resolution to be brokered. They start out uncorrupted by the machine. Perhaps there is a niche that will allow them to defeat it. But then I remember the territory. Not only that, I remember the narrative we are dealing with: even on this small scale, it is the well-worn narrative of contemporary capitalism, and history tells us how it ends. Boom and bust. (Which, incidentally, is a handy analogy for the film’s denouement, which I will not spoil here.)

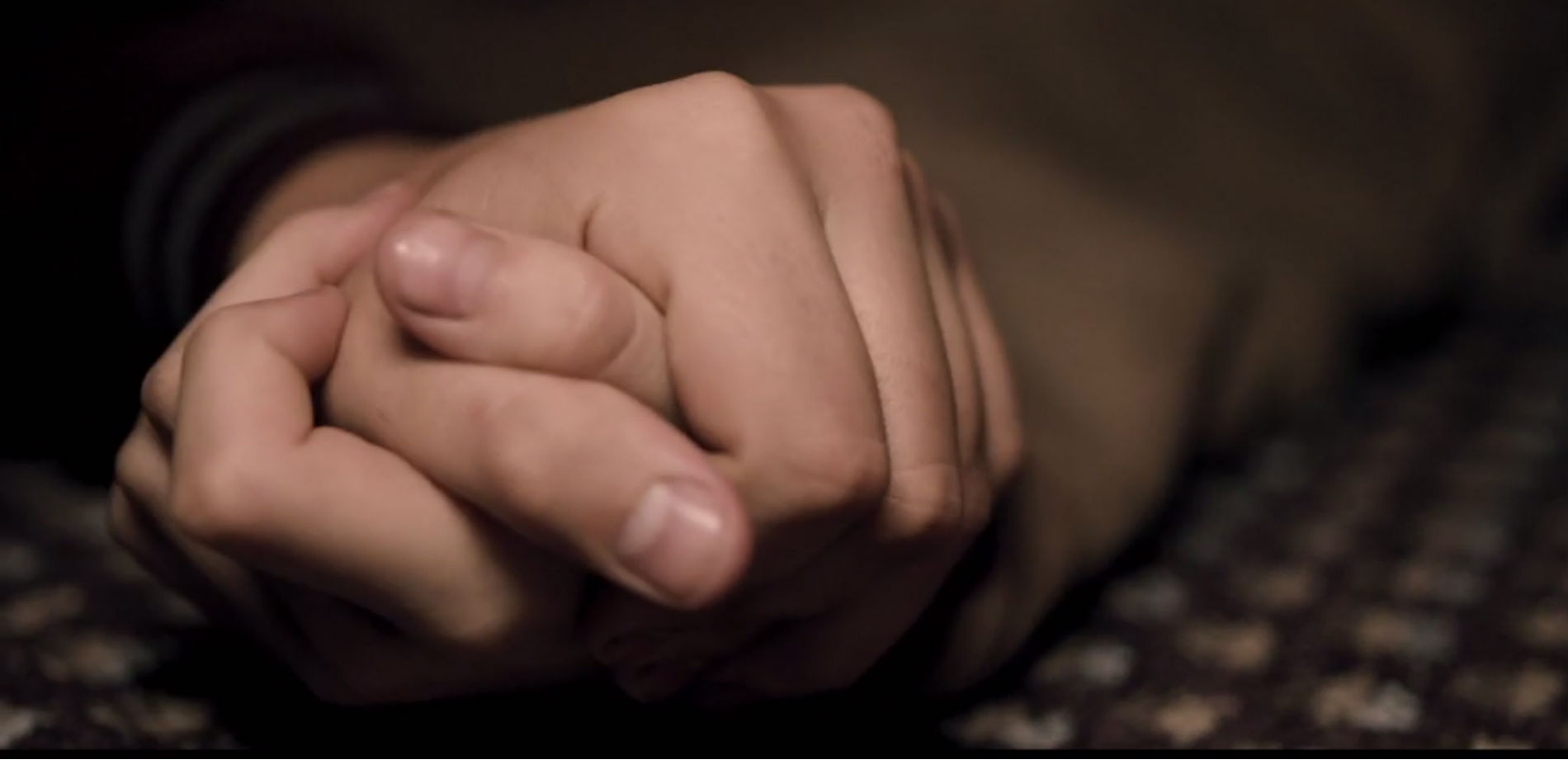

What is telling is that the final passage of the film sees Arbor curled up beneath his bed, just as he had been at the very beginning. A shot of his outstretched hand reveals that his fingernails are still dirty. Moments later his torn, dirty jacket reappears. At some point, although it is not shown, we imagine he will have to return to education, and will do so in uniform still faded and frayed. He will get himself into trouble once more. Perhaps we might see that he has come full circle. The realist would see that he has moved nowhere at all.

For me, what does shift, in the wake of the film, ever so slightly, is the wider discussion on social deprivation. Forwards. Woe betide the critic who with only words talks up the value of art, invests faith in cinema to revolutionise a social issue. But if a new language is to be at the heart of the project – and I believe firmly that it should be – The Selfish Giant undoubtedly offers up a few opening words.