When the Covid-19 pandemic hit and wealthy countries assured poorer countries that ‘help is on the way’, instead of waiting for those promises to materialise, Cuba got to work. Belinda Rawson explores how one of the poorest nations in the world is developing vaccines and sharing them where they’re needed most.

Cuba is one of the poorest nations in the world, yet resilience and scientific accomplishment in healthcare is never in short supply. This Caribbean nation’s innovative Covid-19 vaccine development program and willingness to share its intellectual property and technical know-how, in spite of experiencing its own severe and sustained economic hardship, is providing a lifeline for not only Cubans, but also for many people living in the Global South.

‘Vaccine apartheid’ violates human rights

Ensuring affordable access to medicines (including vaccines) has been authoritatively interpreted by the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights as a core component of the right to health. Yet, the nationalistic practices of high-income countries in vaccine hoarding, and preserving intellectual property laws that protect pharmaceutical monopolies, have proliferated throughout the Covid-19 pandemic.

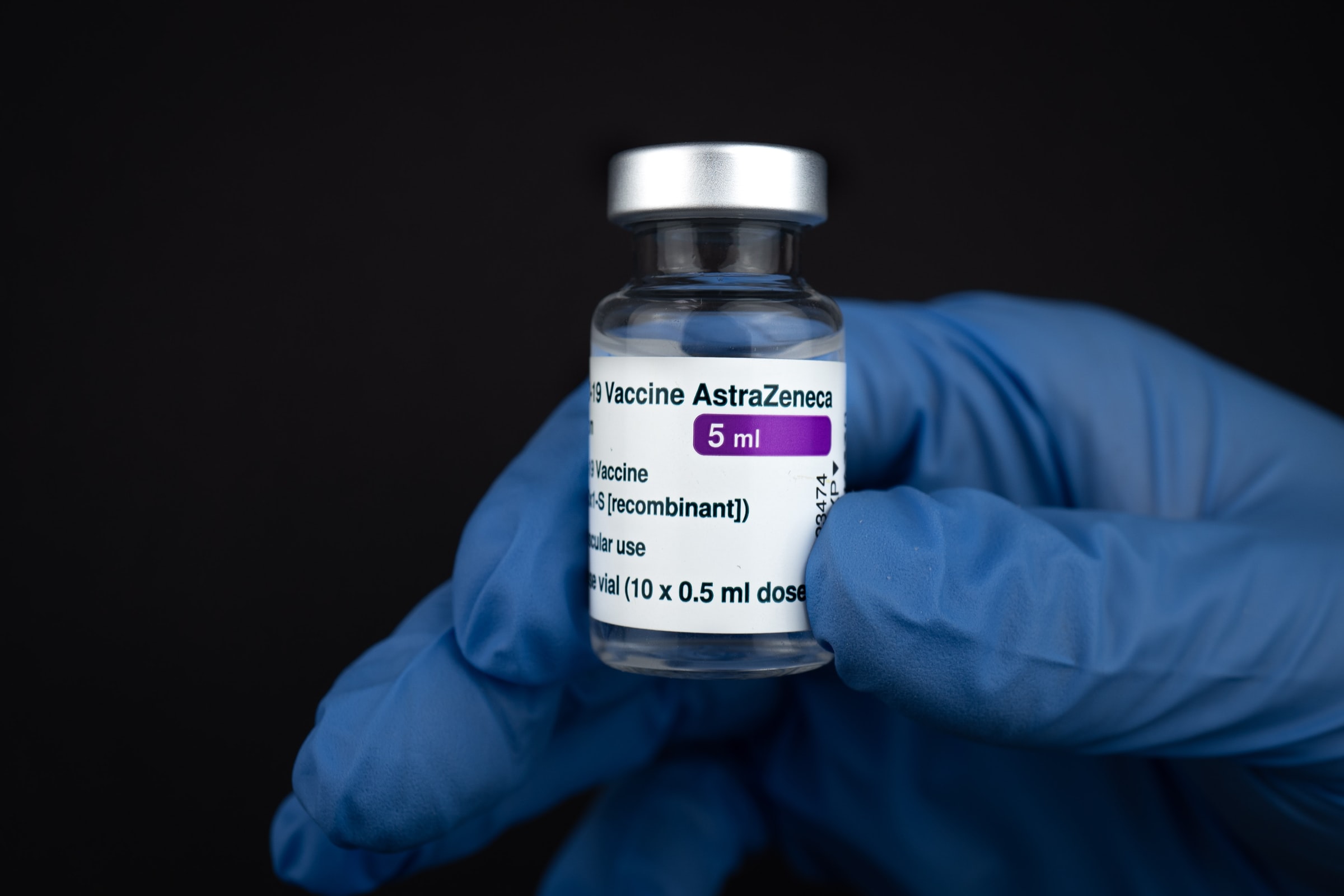

Photo by Mika Baumeister on Unsplash

Despite nearly 70% of the global population being partially vaccinated, the majority of vaccinated people are domiciled in wealthy nations in the Global North, with only 20% of people in low-income countries having received at least a single dose as at the time of writing.

The director-general of the World Health Organization (WHO) has referred to this nationalism as “vaccine apartheid” and condemned it as a “catastrophic moral failure” of our time leading to a “two-track pandemic”. Vaccine apartheid has hampered the equitable distribution of Covid-19 vaccines on the international scale needed to end the pandemic and prevent the emergence of new variants of the highly infectious disease. These practices have also been described by scholars as “a microcosm of neocolonialism that hurts us all”.

Human rights defenders and champions of global health equity have condemned these nationalistic practices. They say they not only worsen the divide between rich and poor countries, causing global inequalities to be exacerbated and leading to human rights violations, but also subvert notions of international solidarity and collective responsibility during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The term “vaccine apartheid” which makes “explicit comparisons to the South African system of institutionalised racial segregation”, is intended to send a strong message about the moral failure of high-income countries throughout the pandemic. In response, more than 100 civil society organisations and humanitarians have mobilised through creating the The People’s Vaccine Alliance, a global campaign to “end vaccine monopolies”.

Cuban Health Specialists arriving in South Africa to curb the spread of COVID-19 via Flickr

Since 2020, countries in the Global South have been advocating for a “waiver” to a World Trade Organization (WTO) agreement that restricts poorer nations’ access to vaccines. Waiving patent rules under the Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement would permit the scale-up of manufacturing of Covid-19 vaccines, increasing global accessibility beyond the borders of wealthy states. After almost two years, WTO member states have agreed to a TRIPS waiver, however, campaigners argue that it has shaped up very differently to what was originally sought and is “absolutely not the broad intellectual property waiver the world desperately needs”.

The international COVAX initiative led by the WHO, Gavi and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), was developed with admirable intentions to “accelerate the development, production, and equitable access to Covid-19 tests, treatments, and vaccines” globally.

But bilateral agreements struck between wealthy countries and pharmaceutical giants have undermined the scheme’s success, and resulted in tokenistic gestures of “goodwill” by wealthy countries “donating” stockpiled vaccines with a short shelf life to poorer ones with little notice, making it difficult, if not impossible, for the latter to use those doses to vaccinate their populations.

In this context, Cuba has emerged as a new protagonist in the story of infectious disease control, becoming a crucial player in the global fight against vaccine apartheid by making moves to vaccinate the Global South against Covid-19.

Cuban vaccines for Covid-19 and human rights

Cuba’s ability to import Covid vaccines for its own population, like the majority of other Global South countries, was severely hampered by the economic and market forces that enabled vaccine apartheid to take root. While wealthy countries paid lip service to poor countries intimating that ‘help is on the way’, instead of waiting for those promises to materialise, Cuba got to work.

Image by gabrielmbulla from Pixabay

It pooled resources and capitalised on its prestigious biotechnology sector by developing five Covid-19 vaccine candidates (Abdala, Soberana 1, Soberana 2, Soberana Plus, and Mambisa). Clinical trial data indicates that the Soberana vaccines have very high efficacy against Covid variants (up to 92.4%). Being subunit vaccines, all of the Cuban vaccines contain highly purified proteins of the pathogen and are deemed to be much safer than whole-pathogen approaches.

These vaccines do not need to be kept at super low temperatures, are inexpensive to produce, and can be easily manufactured at scale, which make them ideal candidates to dispense throughout the Global South.

By mid-2022, over 94% of Cuba’s population (of more than 11 million people) had been vaccinated against Covid-19, and as Cuba is now one of the most vaccinated countries in the world with its astonishingly high rates of inoculation (343 doses administered per 100 people), it has far exceeded the benchmarks of many wealthy nations for Covid-19 vaccines.

The Pharmaceutical Accountability Foundation recently released its ‘Fair Pharma Scorecard 2022’, which ranks Covid-19 medical product developers based on their commitment to human rights principles. Cuba’s Finlay Institute, which developed the three Soberana vaccines, was ranked third (out of 26 pharmaceutical companies globally), having successfully met a number of human rights criteria−particularly in relation to:

- fair pricing and equitable distribution globally (offering Covid-19 vaccines to poor countries for free or at cost),

- its pledge to full technology transfer in order to enable producers in low- and middle income countries to manufacture Cuban vaccines for their local populations,

- and its commitment to not enforce exclusive patent rights on its Soberana 2 vaccine which it considers ‘open source’.

Cuba’s Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (CIGB) which developed the Abdala and Mambisa Covid-19 vaccines (which are intranasal, needle-free vaccines), was not far behind, ranking seventh based on the same criteria.

Photo by Ricardo IV Tamayo on Unsplash

Cuba has itself been subject to criticism by human rights organisations for restrictions of basic civil liberties, with critics highlighting widespread government repression of dissent, restrictions on freedom of expression, arbitrary detention of political activists and discrimination against LGBTI people.

While Cuba’s overall human rights record is therefore much debated, its achievements in providing vaccines that are important in realising the right to health for not only its own citizens but for those in many other developing countries are laudable.

Photo by Ricardo IV Tamayo on Unsplash

How did Cuba become a trailblazer in vaccine development?

Cuba has historically enjoyed a stellar reputation for demonstrating solidarity with its Global South comrades in providing emergency health care and facilitating access to locally produced essential medicines and health technologies despite its own limited resources.

The history of Cuba is a turbulent tale of repressive colonisation by the Spanish, a hard-fought revolution and war of independence, economic upheaval due to dependency on the Soviet Union (a communist ally before its collapse), and political and economic isolation throughout six decades of a debilitating trade embargo imposed by the US.

Cuban Health Specialists arrive in South Africa to support efforts to curb the spread of COVID-19 via Flickr

Cuba’s biotechnology successes are in part attributable to former President Fidel Castro making health care “a defining characteristic of its Revolution” by investing early in biotechnology and scientific education in the early 1950s. The country’s investment in social services and health care are unrivalled in the developing world.

Castro’s vision manifested in the creation of a viable, state-led domestic pharmaceutical manufacturing industry which survived protracted periods of significant economic and social turmoil caused by 60 years of crippling trade embargos. This instability, much to US dissatisfaction, increased Cuban resilience and independence, while also fuelling domestic innovation. Cubans have historically been pioneers in vaccine development. Since Cuba’s national immunization program was introduced in 1962, Cubans are vaccinated against 13 potentially fatal diseases – and many of these vaccines are developed and manufactured in Cuba.

Since the 1960s, Cuba has also been known for deploying throughout the developing world its award-winning Henry Reeve International Medical Brigades, comprised of health care workers expertly trained in infectious disease, to offer front-line emergency medical treatments to patients in need. While there are too many remarkable stories of Cuban medical diplomacy to recount here, we can acknowledge a few.

During the 1970s, Cuba sent its first doctors to Angola, and by 1982, many thousands of Cuban doctors, nurses, and other healthcare workers were serving in 26 countries across Africa, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia. Many more were on the ground during the height of the 2014-16 Ebola crisis in West Africa, and almost 40 countries across five continents received Cuban medical support during the Covid-19 pandemic. This commitment to equality in healthcare has saved an immeasurable number of lives globally.

Photo by Yerson Olivares on Unsplash

How is Cuba planning to protect countries in the Global South against Covid-19?

To combat vaccine apartheid, Cuba has already donated doses of homegrown Covid-19 vaccines to Syria and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, as well as exporting doses to Argentina, Iran, Venezuela, Vietnam and Nicaragua.

Cuba has also pledged to share knowledge and technical know-how with Global South countries to enable local manufacture of the vaccines and will assist countries with building medical capacity and training for vaccine distribution by deploying its Henry Reeve International Medical Brigades. Iran has already become the first country to begin local production of the Cuban Soberana 2 vaccine at scale, with many more including Vietnam, Argentina and Mexico, to shortly follow.

State-run conglomerate BioCubaFarma, which coordinates the country’s vaccine research institutes and manufacturing facilities, recently made an application to the WHO to have three of Cuba’s vaccine candidates (the Soberana series) approved under WHO’s Emergency Use Listing procedure−a risk-based assessment process which enables countries to expedite regulatory approval for unlicensed vaccines. WHO approval will be an important step in enabling Cuba to fulfil its commitment to export high volumes of vaccines to a greater number of low- and middle- income countries at “solidarity prices”.

Photo by Ricardo IV Tamayo on Unsplash

While Cuba has been the first country in Latin America and the Caribbean to develop its own vaccine candidates for Covid-19, many more countries in the Global South are anticipated to shortly follow suit. The mRNA vaccine technology transfer hub in South Africa has, with WHO’s support, already made headway in supporting vaccine manufacturers from Argentina, Brazil and Ukraine to produce mRNA vaccines (similar to the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines for Covid-19) locally. UK organisation Global Justice Now has praised this as a huge development allowing for revolutionary medical technology to be “prised out of the hands of the profit-obsessed transnationals” and into the hands of those who need it most.

Will other countries in the Global South follow Cuba’s lead?

While Cuba has not been the only country to engage in vaccine diplomacy during the pandemic, its commitment to share vaccines and technology with Global South countries will assist in combatting vaccine apartheid. Cuba’s ingenuity in developing Covid vaccines was necessitated by a range of factors−its tumultuous past, beginning with its violent colonisation; the continued trade embargo by the US leading to the political and economic isolation of Cuba; and the monopolisation of Covid-19 vaccines by wealthy nations to the detriment of poorer ones. Its Covid-19 vaccine successes were also possible due to Cuba’s prestigious biotech sector and extensive experience in vaccine development, and its inclination to assist other countries in this time of need is likely to be grounded in its long history of medical diplomacy.

Cuban Health Specialists arrive in South Africa to support efforts to curb the spread of COVID-19 via Flickr

Many countries in the Global South already have the technical capabilities to develop Covid-19 vaccines locally, but Global North countries continue to curtail these efforts by exerting either direct or indirect control over sovereign countries in the Global South−a pernicious habit that they just can’t seem to shake. As new forms of neocolonialism become increasingly contested, Cuba’s lead will give the Global South continued impetus to innovate for itself when faced by health crises.

Read more: