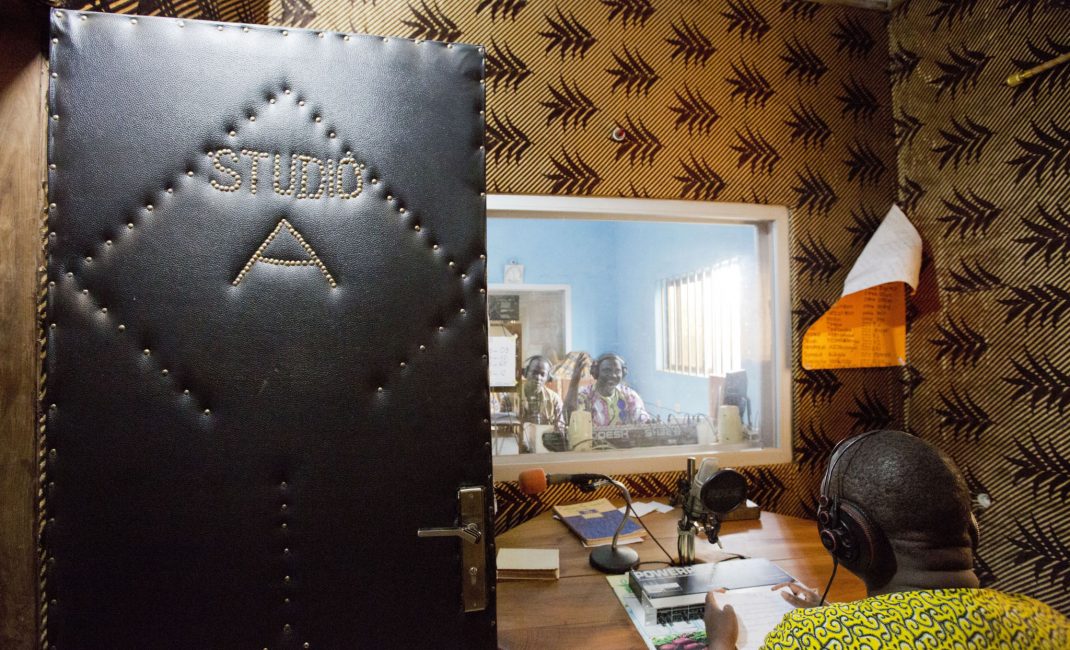

According to the World Health Organisation, around one billion people worldwide are affected by one or more Neglected Tropical Diseases. Yet these receive little attention and resources, despite their impact on economic development and quality of life. The WHO considers neglected tropical diseases as both a public health and a human rights issue. And while many diseases have been known by specialists for a long time, they only make headlines and enter public consciousness during times of crisis, as demonstrated with the recent ebola and zika epidemics. Raising public awareness of the multiple health problems that beset developing contexts, including many African countries, is vital to ensure some kind of coordinated response. This photo essay by Spanish photojournalist Ana Palacios on the people affected by Buruli ulcer in different locations in south Benin, in collaboration with the NGO Anesvad, gives us a glimpse of the human cost of neglecting this tropical skin disease.

*WARNING: GRAPHIC PHOTOGRAPHY FOLLOWS*

AFRICA’S MYSTERIOUS SKIN

Like snakeskin. That’s how your skin looks, with a kind of diamond pattern, when you have a skin graft done in Africa. That’s if you’re lucky and they have the little stretching machine that makes holes in the skin cut from you so it can then be stretched like a mesh over the wound, like one of those string shopping bags. . Otherwise, after the operation when they use strips of your healthy skin to cover the diseased patches, it can look like a bar code has been hand drawn all over your thigh.

This is how Boris, a 28 year-old Nigerian, describes the consequences of Buruli ulcer, “the mysterious disease” whose origins are unknown but has a devastating impact on its victims. Boris has just had an operation and he’ll have to stay in the hospital at Couffo, in Benin, for at least a month for ongoing treatment and rehabilitation.

BENIN HAS MORE FAITH IN WITCH DOCTORS THAN IN DERMATOLOGISTS

In Benin, home of voodoo, there’s a strong tradition of going to traditional witch doctors and shamans when someone gets sick. But Gbemontin Hospital is getting more visitors year after year, and it’s brimming with patients who see Sister Julia Aguiar as some sort of mystical skin guru. Last year, this “dispensary”, as the facility is referred to in the Benin registry, treated more than five thousand people and carried out over 40,000 medical consultations, a reasonably high figure in a country with 10 million inhabitants.

Surprisingly, despite all the financial difficulties and the lack of staff, Sister Julia has turned this small rural hospital in Benin into a ground-breaking world class centre for the treatment of Buruli ulcer.

WHAT IS THE MYSTERIOUS DISEASE?

Buruli ulcer got its name in the 1960s from the high numbers of people who were getting infected and displaying the same symptoms across the county of Buruli, in Uganda. Nobody really knows where the disease came from, only that it’s caused by mycobacterium ulcerans bacteria, from the same family as leprosy, and that it’s mainly transmitted via water. Benin is one of the world’s major endemic countries for the disease, along with Ivory Coast, Ghana, Cameroon and Togo.

It’s classed as a Neglected Tropical Disease and the infection destroys skin and soft tissues, causing huge ulcers, usually on the arms and legs. In Africa, the disease is often diagnosed too late because it’s difficult to identify, it’s painless and doesn’t cause a fever. If it’s not treated properly with a cocktail of antibiotics, the ulcer goes on the attack, devouring tendons, even bones, disfiguring the body and deforming the sufferer’s limbs, to the extent that amputation may be required. The risk of mortality is low, although secondary infections may prove lethal.

FIRST STEP: PREVENTION. FINAL STEP: SKIN GRAFTING

The disease began spreading at an alarming rate towards the end of the 20th Century. In 2004 the WHO decided to intervene by adopting a resolution aimed at increasing surveillance of Buruli ulcer and promoting research. The disease continued to spread geographically, with sufferers now recorded in more than 30 countries across Africa, Asia and the Western Pacific, prompting the WHO to issue a new alert in 2013. A new resolution was adopted, calling member states to step in and put measures in place to improve the health and social welfare of population groups affected by Neglected Tropical Diseases.

After awareness raising comes prevention, treatment (with or without surgery) and rehabilitation, followed by skin grafting at the very end of the disease process. The hospital monitors patients whose treatment has been completed to supervise their progress and ensure there are no new sources of infection.

OFFICIAL VOICES FIGHTING THE DISEASE

Didier Agossadou, who heads a government plan set up specifically for this purpose, the National Programme for Fighting Buruli Ulcer, tells how 80% of cases picked up in the early stage – category I – can be cured:

“Early diagnosis and treatment with antibiotics has been really effective, even reducing the net morbidity rate associated with the disease in recent years. If it’s diagnosed at the advanced stage (category III) or treatment starts too late, the result is lengthy hospital stays, which are costly for both patients and the government, plus there is a 25% risk of permanent side effects – shortening of limbs leading to reduced mobility. That’s why early detection is so important, to prevent people suffering from these irreversible injuries”.

“To control this disease it’s absolutely crucial to raise awareness in local communities and train medical professionals so we can achieve effective prevention, guarantee early diagnosis and ensure proper treatment,” says Yves Barogui, who is the only practising doctor for more than 100,000 inhabitants and who runs the Comuna de Lalo Health Centre in Couffo, specifically for treating Buruli ulcer.

Barogui and Agossadou are grateful that NGOs like Anesvad, a Spanish NGO, works jointly with the Benin Ministry of Health to provide equipment and facilities at clinics like his. Otherwise, he would have no access to anaesthetics, surgical instruments, gurneys or beds for post-operative recovery. In short, he wouldn’t be able to operate and patients wouldn’t be cured.

The central aim of the government and its partners is to eradicate Neglected Tropical Diseases, especially Buruli ulcer. In Benin, misinformation and barriers to accessing medical care still result in widespread infection. The ultimate goal is to eradicate leprosy and control Buruli ulcer by 2020, in line with WHO targets and the Sustainable Development Goals, which seek to “eliminate Neglected Tropical Diseases” by 2030. Raising awareness of Buruli ulcer is a step in the right direction.

All images by Ana Palacios.