While new HIV infection rates have been steadily falling worldwide, in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus the rate of HIV diagnosis per 100,000 inhabitants has risen by 126% since 2004. In that area a record 100,000 new cases are diagnosed each year, which make up nearly three quarters of new cases in Europe.

Romania is one of the hotspots for this new HIV epidemic. The economic downturn and reduced funding for prevention efforts and treatment programmes have led to the spread of this virus, especially among the most vulnerable sectors of society, such as drug users, sex workers and the homeless. HIV infections among communities at risk have skyrocketed: among IDUs (injecting drug users) the rate of HIV grew from 1% to 53% between 2007 and 2012, affecting mostly the capital area. Thousands of people in Bucharest, many of them young adults born after the fall of Ceaușescu’s regime, live between the streets and the sewers in unsavoury conditions worsened by disease, drug use, and unprotected promiscuity.

These figures continue to rise as a consequence of funding cuts for HIV prevention activities in Romania. The EU has discontinued its financial support for distribution of clean needles and syringes. The Romanian government has been slow to respond, despite clear research indicating that new infections drop up to 80% where free supply programmes are in place. Against the backdrop of the unprecedented economic crisis and the simultaneous boom of legal highs, HIV has soared since 2009. And in the homeless communities around the Gara de Nord train station in Bucharest HIV infection rates are close to 80%.

‘Romanian Nightmares’ is a journey in the communities afflicted by HIV. The author met drug users, sex workers, orphans and homeless people in squats, ghettos and hospitals. This journey is about the forgotten victims of AIDS in the only European capital facing an HIV epidemic while global infection rates are falling.

Florin is lying in bed. His arms unnaturally thin, his legs barely skin and bones. He’s been kept alive by a respirator at the Dr Victor Babeș Hospital in Bucharest for about a month, the doctors say he only has a few weeks left now.

What is killing him is a virus we no longer talk about in Europe. It seems so far removed from us, perhaps an African or Asian problem, but certainly not something we worry about here. Florin contracted HIV two years ago, when he was only 15. At that time he had been living on the streets for 5 years, moving from one abandoned building to another, and sometimes down in the sewers of the city. Much like Florin, another 25,000 people in Romania, mostly in the capital, are living with HIV.

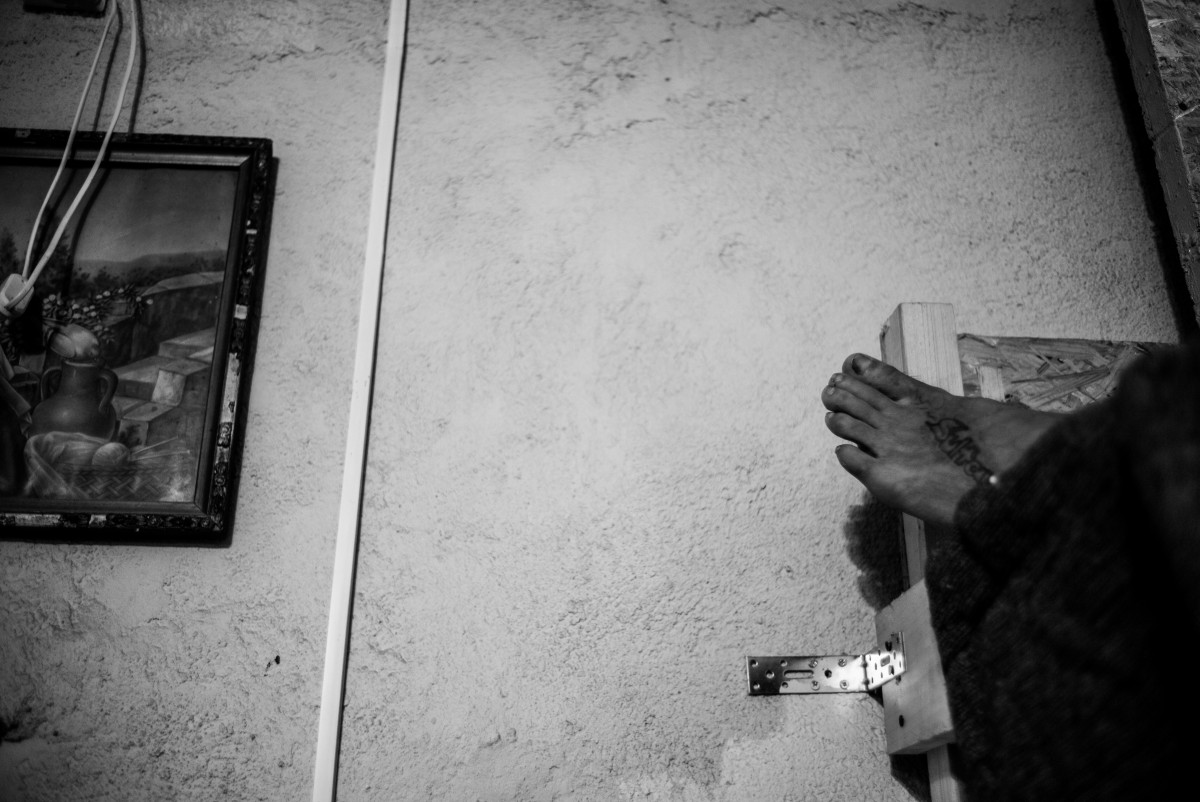

Amer shows the scars on his arms due to the heavy use of drugs

25,000 people in Romania, mostly in the capital, are living with HIV

“It is a real and proper epidemic. An epidemic which is killing thousands right in the heart of Europe, without anyone saying a word,” says Dan Popescu, of the NGO Aras, which provides assistance to the most vulnerable groups, such as drug addicts, prostitutes and the LGBTQ community. It is precisely amongst these groups that HIV is spreading. In 2007, among drug addicts, the percentage of infected people was 1%; in 2012 it had risen to 53%. But where does this epidemic originate from? And why is it so difficult to contain in a country now part of the European Union?

A young boy sniffs painting in a squat occupied by drug users in Bucharest

“There are two main reasons,” says Dr Adrian Abagiu of the Matei Balș Hospital in Bucharest. “First, with the entry of our country into the European Union in 2007, the Global Fund has cut funding for HIV prevention initiatives, as well as programmes aimed at reducing the effects of HIV/AIDS. Then in 2009, we experienced the boom of so-called ‘legal highs’. These substances are far cheaper and much more readily available, in addition to having now been legalised. This has contributed to increase in drug addicts who need to inject themselves with these new synthetic drugs up to 20 or 30 times a days now, which multiplies the risk of contracting contagious diseases such as HIV.”

Inside a makeshift house near Gara de Nord where drug users spend their days

Florin used to live in what is known as the community of the Gara de Nord. Close to forty or fifty people, of both sexes and all ages, with no home, no jobs, no possessions, congregating around the central station of Bucharest to find shelter. During the freezing Romanian winter, they sleep down in the sewers to survive the cold. In the summer they return to the surface. They walk around the streets and parks like zombies, begging in parking lots, scraping together just enough for the next dose. Then they run back to their makeshift shelters, tiny brick structures, just behind the hospital, facing the central station. There, among bunk beds and gas cylinders they use for cooking, they sleep, eat and take drugs constantly. The thick air reeks of glue snorted by the younger ones; syringes are littered all over the floor.

The entrance to the sewers where drug addicts and homeless live during winter

The top dog of this community used to be an ambiguous, charismatic figure. He has since been arrested (in July 2015) for drug trafficking. He goes by the name of Bruce Lee. This is what this man in his forties, with lots of tattoos and scars on his arms, with grey gel in his hair wants to be called. He walks the streets with a 30 cm knife tucked under his belt, along with snap hooks and keys attached to his jacket.

“I’m trying to help these people, to give them a home,” says Bruce Lee, “because just like them, I never had anything either.”

Here nearly everyone is ill

Not a word about drugs, and certainly no mention of the diseases infesting this building: TB and hepatitis C. Here nearly everyone is ill. Aras volunteers come here at night, three times a week, with an ambulance, to supply new syringes and condoms to these people in an attempt to try and slow down the spread of infections. According to their statistics, 80% of this community is HIV positive.

Two drug users injecting themselves with legal highs

“I was born in an orphanage, I was abused more than once, and when I was 12 I ran away. The street is my home, and drugs are the only entertainment I have. It’s a distraction, the only way I have to forget,” says Nico, 17 years old, HIV positive, snorting glue from a black plastic bag.

Since joining the EU, the severe economic downturn has become the primary concern for state institutions. The desperate young people at Gara de Nord, many of whom are children of Ceaușescu’s fallen regime, are a social ill to be kept hidden away. Only a handful of local charities have taken any notice of them. And one brave woman stands out: Raluca Pahomi. Four years ago she decided to take care of the homeless people of Bucharest. She brings food, she helps with any paperwork, and she hosts some of them in her house.

A man regains consciousness after taking some drugs

“This situation is outrageous; these people are dying in the streets without anyone noticing them. HIV contagion and drug addiction rise together. Cases of TB and hepatitis C have also exploded over the past few years. And all these people, and I mean thousands and thousands, have no rights, no accessible healthcare, not even the right to die humanely.” Raluca has asked for permission to bury Florin when his time comes. The local administration said no.

The epidemic is invisible in central Bucharest, among the busy shops, trendy bars and upmarket restaurants

People living with HIV still face stigma and discrimination across Romanian society. They are confined to living on the margins of urban life by the government and local institutions, who are yet to understand how social inclusion and prevention are the only ways forward to limit this epidemic. The epidemic is invisible in central Bucharest, among the busy shops, trendy bars and upmarket restaurants. But you may notice whilst walking along the streets of Ferentari, one of the biggest ghettos of the city, where mostly Roma people live.

Soviet era buildings in Ferentari district in Bucharest

Here, the luxurious villas of the nouveau riche and the squalid grey buildings of the communist era in appalling states of disrepair coexist. Drug addicts appear from behind every corner as soon as the Aras ambulance arrives. The people form a crowd around the van as they wait for clean syringes. Some even take buckets full of used ones, so that they may pick up more new ones. Drugs, like HIV and TB spare nobody here. Substance abuse and diseases spike during times of crisis, when the poor become even poorer. European austerity measures and the cavalier attitudes of Victor Ponta’s government run the risk of ruining a whole generation. One in four Romanians between 19 and 24 has been diagnosed as HIV positive. These are the highest figures in the EU. By comparison, in Italy only 6% of that age group are HIV positive. There is no upper or lower age limit to contracting the disease, which in the vast majority of cases ends in death.

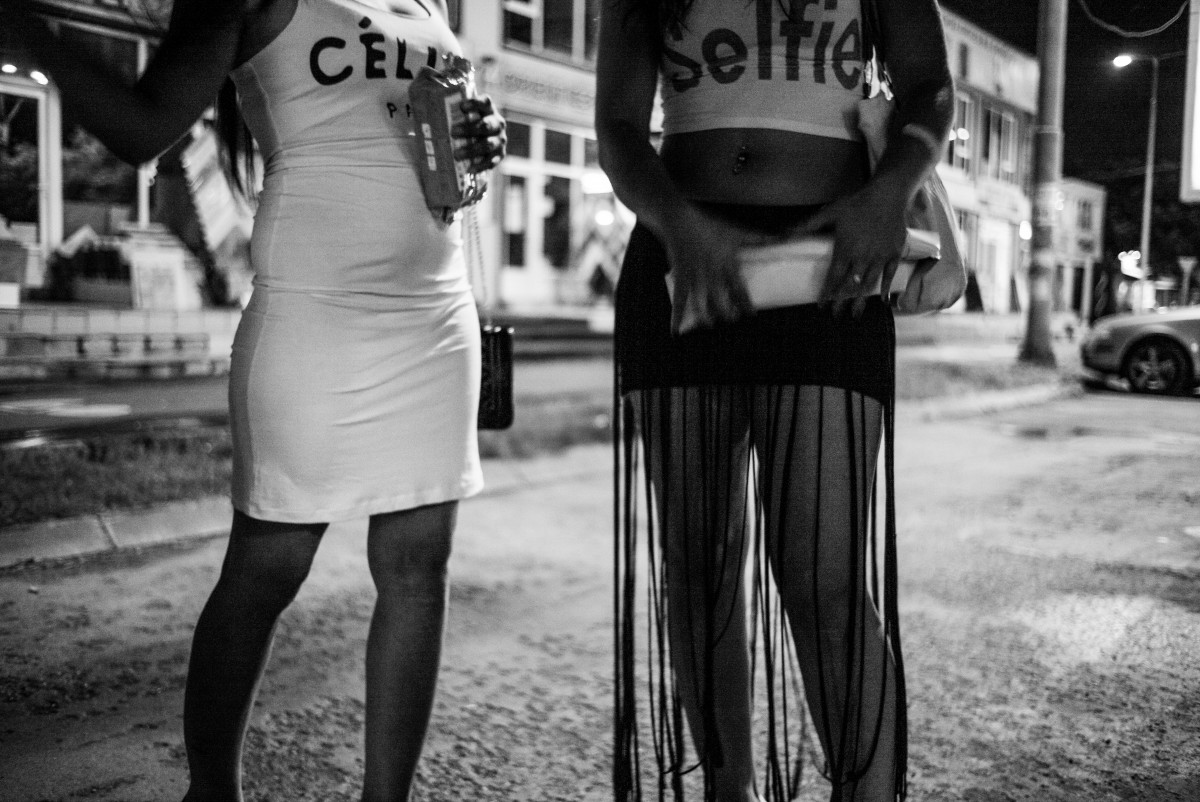

Two young sex workers have just been tested for HIV by Aras volunteers

He could be cured, like some of his friends, and live. But his condition of homelessness, social marginalisation and vulnerability, teamed with the prejudice of Romanian society and institutions, have sentenced him to a premature death

The methadone distribution centre at the Matei Balș Hospital receives more or less between two and three hundred people per day, most of whom are teenagers. Just like Romeo, Nomi, Mona, and Santo, who have yet to reach their twenties. At night they wander the streets of Bucharest snorting glue and injecting ‘legal highs’ into their veins. They say Santo has only another month to live; he has been HIV positive now for three years. He could be cured, like some of his friends, and live. But his condition of homelessness, social marginalisation and vulnerability, teamed with the prejudice of Romanian society and institutions, have sentenced him to a premature death.

A drug addict near Bucharest main train station

“When the Global Fund axed funding to Romania because it joined the EU, the government should have raised its voice to say that the threat of HIV had not yet disappeared,” says Dan Popescu, “so the combination of the economic downturn and the ready accessibility of new synthetic drugs, most of which are legal and found quite easily in high-street shops, was enough to make the situation collapse. Studies demonstrate that efforts to reduce the damage are a very effective tool to fight HIV spreading further, but politicians seem not to quite understand. Better to keep the whole thing hidden, not to speak about it at all, and finance some other social problem with the small amounts of funding available.” Still, it is always the most marginalised who die, those who are the least important. And this is in Europe in 2015.

All photos by Tomaso Clavarino.