After spending months piecing together details about the life – and death – of Carlington Spencer, our writer-in-residence Rebecca Omonira-Oyekanmi shares the opening chapter to his story. Carlington, 38, held at Morton Hall, was one of six people who died last year in or shortly after transfer from immigration lock-up.

This article was first published on Shine a Light, an investigate journalism & storytelling project that publishes first on openDemocracy.

Laura is 33 and lives in a small terrace house on the edge of Derby. One Thursday in September last year she finally got her baby daughter home — she’d been born 10 weeks early and spent four weeks in the hospital. Back at home, Laura felt like normal life was about to begin again.

But that same day, 50 miles away, something else was happening. Laura’s friend, her soulmate, her former partner, fell gravely ill. His name was Carlington Spencer. Friends recall him lying motionless on his bed, dribbling, calling for help, struggling to breathe, his left arm and leg limp.

Carlington was an immigration detainee, held by the UK Home Office at Morton Hall detention centre, a former prison. Over months I’ve spent time with Laura in Derby, I’ve visited Carlington’s friends, two locked up at Morton Hall, one at Brook House detention centre close to Gatwick Airport. I’ve tried to piece together Carlington’s story, to get to know him a little, to find out how he ended up dead.

Due to ongoing legal proceedings I can’t share everything I’ve learned just yet. On Monday (Sept 3) a pre-inquest review will be held into Carlington’s death. There has been no date set for a final hearing. For now, I will tell you a little about Carlington and how he came to be in immigration detention.

***

Laura and Carlington’s story began more than decade ago in Jamaica when they were both in their twenties. A skilled tradesman, he ran his own metal fabrication business fitting doors and windows.

His home town was small and strong on community. Laura told me that Carlington taught local young people the trade, helped them when they were broke, made sure they had clothes and shoes.

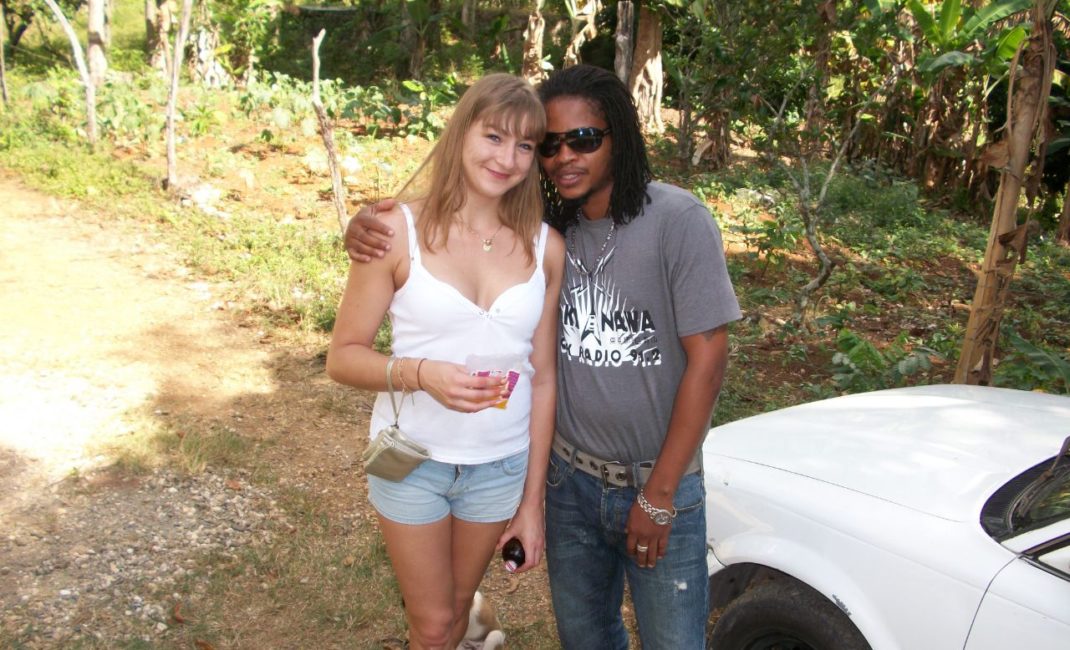

Laura and Carlington in Jamaica (published with permission of Carlington’s family)

Laura, born and bred in Essex, was in Jamaica visiting a friend when she met Carlington. He made her laugh. They enjoyed each other’s company, he was kind and fun, they shared a passion for music.

Laura fell in love with him, and stayed in Jamaica for two and half months. She would have moved there, but she had responsibilities back home. Soon after she met Carlington, she took on caring for her 13 year old cousin full-time and another 14 year old cousin part time. For a while it could only be a long distance relationship with Carlington.

Laura and Carlington getting married (published with permission of Carlington’s family)

They made it work and married in 2008. Two years later Carlington moved to the UK and they started a baby together. But then they lost the baby. Things fell apart. Carlington took to drink, he slept with someone else, their marriage collapsed. Laura was done with him.

Carlington fathered a son. For a while he lived with his new family in Derby. That didn’t work out. He moved to Birmingham and met another woman. His drinking got worse, he made mistakes, did things he regretted, got into serious trouble. Convicted of charges including criminal damage, skipping bail and possession of crack cocaine, he was sentenced to two years, 10 months and seven days. While on bail during this time Carlington was beaten up, hit over the head with a hammer, taken to hospital. There, doctors diagnosed his diabetes. He went straight from hospital to prison.

Not long before the prison sentence Laura and Carlington had started talking again. He wanted her back, to be a married couple again. She refused, but did visit him in prison. There she glimpsed Carlington as he once was. Sober Carlington was calm and reflective, a different person to his hurting drunk self. He began the process of applying for formal visitation rights to see his son, then four years old, but it was too expensive to do from prison. He’d sort it once he was out.

Political context

By May 2017, Carlington had served his sentence. If he’d been born in Britain, he’d be free. But since he was Jamaican born, special rules applied to him. Since 1971 anyone not a British citizen handed a prison sentence of 12 months or more could be deported after serving their time. The Home Office was supposed to consider each and every case and decide whether to deport.

The decision-making varied depending on the political weather. When in 2006 the then Home Secretary Charles Clarke couldn’t explain why more than 1,000 foreign national offenders hadn’t been considered for deportation, he lost his job. Clarke’s successor John Reid wanted to show that he was tougher.

He brought in a new law in 2007 to ensure that anyone not British and sentenced to 12 months or more in prison would automatically be considered for deportation. The Home Office would be obliged to deport them. Thanks to Reid, there’d be less room for discretion – a Home Office case worker must seek deportation before considering the unique circumstances of a case. And it became even harder for people to challenge a removal order.

Then Theresa May made it harder still. As Home Secretary between 2010 and 2016, she hired more Home Office case workers and gave them targets to increase deportations of foreign national prisoners. More laws were introduced which restricted the rights of people to challenge deportation.

Even though Carlington was a father to a British child, there was slim chance of his being allowed to stay in the country after his sentence. It followed that when he had served his time, he was moved to Morton Hall, the immigration detention centre in Lincolnshire.

Morton Hall

Laura visited nearly every week. She’d drive an hour and half from her home in Derby to Morton Hall, a sprawling old prison building surrounded by farmlands. She’d sign in at the visitor’s centre, a white-walled cottage next door to the prison. Once she’d handed over her identification, she would wait in the reception centre for anything up to an hour on busy days. Visitors are let in one by one.

When it was her turn Laura was escorted through the first two gates. Then she was searched. After that, she’d get sent into the visiting room. It had the feel of a school canteen with rows of chairs and low tables. There was a little tuck shop selling tea and coffee in small plastic cups. Behind a large desk sat the guards keeping watch. Small children played in an area to one side that had cushions, books and toys. Visitors entered through one door, the people detained would come through another, escorted by a guard, keys jangling. Laura would watch the locked door, waiting for Carlington to come through.

They would talk and talk. He enjoyed listening, joking around again, he wanted to know how her pregnancy was going, what she would name the baby. Laura had split up with the baby’s father. It was good to be able to share things with Carlington.

Laura tried to visit Thursdays for the extended visiting hours. She could arrive around 1pm and stay until 8pm. Sometimes the staff offered them dinner. Carlington would tease, Aw, I’m bringing you out for a meal.

He was always trying to get back with her, pick up where they left off. But Laura said if anything was to happen, it would have to be from scratch. She’d wait and see if he could stay sober on the outside.

Carlington and Laura (published with permission of Carlington’s family)

Whatever happened they were close friends and they made plans. They talked about moving to Jamaica together. Carlington wanted to open a pizza restaurant in his home town. He was a good cook and thought there was a gap in the market. Laura did the research, costing pizza ovens. If she was to move, it would have to be in 2018, when her little daughter was stronger.

There were times when Carlington wanted to stay in England. For his son. At other times, he believed he could find a way to make a father-son relationship work from Jamaica. It was anyway impossible to make firm plans from inside Morton Hall, with no money and no legal advice.

Laura and Carlington tried to figure out a way to get him back to Jamaica quicker. It wasn’t simple. Laura couldn’t just book a ticket online, it would need to be done through the Home Office. Carlington would have to be deported formally, escorted by a guard, not on a flight of their choosing. It was frustrating, and kind of crazy. He wanted to get back to Jamaica but he had to stay locked up in Lincolnshire, while the Home Office took its time arranging to deport him.

Laura’s final visit to see Carlington at Morton Hall was at the end of August. Complications with the birth of her daughter kept her away after that. The baby, arriving 10 weeks early, had to spend her first four weeks in hospital.

And then when at last Laura’s baby was released from hospital and home with mum, Thursday 28 September 2017, there came a worrying phone call.

The caller was a man who had been detained at Morton Hall and was now free. He had spoken to other men locked up at Morton Hall. They said Carlington was ill, that he’d had a stroke.

Laura didn’t know the man and supposed it might be just rumours, people making trouble. She called Carlington. No answer. She sent texts. Are you alright? I haven’t head from you. Nothing.

She called Morton Hall. Though she’d been a regular visitor that summer, staff refused to tell her anything. Said they couldn’t, since Carlington had no next of kin details on file.

Around 7pm the next day, Friday, a man from the Home Office phoned. He was the first official person to call. He told Laura that Carlington had been taken to a hospital, he didn’t know which. Once they had located him she would be told.

On Sunday 1 October 2017, Laura was at home with her mum and her new baby when the phone rang. It was Queen’s Medical Centre in Nottingham. They said Carlington had swelling on the brain. Doctors had operated on the Saturday night. He was stable, they said.

Laura and her mum discussed rehabilitation, how she would cope looking after Carlington and a small baby. Laura’s mum reminded her that it would be big job, he would need emotional support as well as physical. Later Laura told me about her grandmother, who’d died of a stroke, at 83. But this should have been different. Carlington was just 38. She had expected him to recover.

And that Sunday morning she believed Carlington would pull through. She thought about going in to see him, but her mum said, no let him rest, he’s just had a big operation. She could visit tomorrow.

The next day, Monday, around 11am, Laura received another phone call. Someone who said they were from the Home Office. Not the man she had come to know as her family liaison officer, someone new. This man said Carlington had been released from custody. The guards who’d watched over him at the hospital had left and gone back to Morton Hall. Laura was confused by this and asked him to explain what he meant. The man said that Carlington wasn’t fit or well enough to return to Jamaica. He was no longer a detainee.

So that was good news, wasn’t it? Carlington was free.

But when Laura arrived at Queen’s Medical Centre hospital later that day, two doctors pulled her to one side, into an office. They hadn’t wanted to tell Laura over the phone. Carlington was dead.

***

Morton Hall is run by the Prison Service on behalf of UK Border Agency. When I called the Ministry of Justice for comment, they directed all questions to the Home Office. The Home Office said they were unable to comment. A spokesperson provided this statement: “An inquest into the death of Mr Spencer remains open and is awaiting the conclusion of the Prisons and Probation Ombudsman. We are therefore unable to comment.”

- Due to ongoing legal proceedings we are restricted from reporting more at this stage but we will return to the story of Carlington Spencer in due course.

This article was first published on Shine a Light, an investigate journalism & storytelling project that publishes first on openDemocracy.

Illustrations by Rana Younis.