China’s crackdown on fantasy literature and video games poses a critical obstacle to readers, authors, and those who seek to make these works accessible. Why restrict these apparently innocuous stories? Eric R Stone interviews censored writers who describe how censorship and outright banning of certain concepts, words, and allusions render works of fiction unintelligible.

In 2019, the year China celebrated the 70th anniversary of the People’s Republic, a million voices fell silent overnight.

That night in May, online novels disappeared in a mass digital book purge, ordered by the government and carried out by independent hosting platforms.

Overnight, an estimated 1.2 million books were removed from the platform Qidian alone, according to an article on Openbook.org.tw. Later the same month, JJWXC.net – a similar online book platform with over 16 million users – was forced to partially shut down for “self-auditing” as well.

The deleted works weren’t the manifestos of radical activists, nor the blueprints for a political revolution. They were internet fantasy novels, similar to Twilight or a work of Tumblr fanfiction.

Of the 1.2 million removed from Qidian, for example, 350,000 were mystical fantasy novels (Xuanhuan), 140,000 were kung-fu fantasy (Xianxia), 80,000 were regular fantasy, 80,000 were science fiction, and 70,000 were based on video games, listed a China Digital Times article, citing a post from a Weibo user with the handle “@bukezhi.”

Beijing 2017 Pirated and Illegal Publications Disposal Event

And many of the works that survived the purge were subjected to puzzling redactions.

Plot Surgery

“Who ordered you to make the sacrifice?” Klein said in a low voice.

Since attaining Sequence 4 and becoming a Bizarro Sorcerer, Klein could now do more than just read the Marionettes’ unconscious thoughts; utilizing his enhanced Spirit Body Threads mastery, he could essentially act as a medium. Still, the higher level the Marionettes, the less effective his medium abilities were on them.

This is an excerpt from a Lovecraftian, steampunk, Victorian-era web novel called Lord of the Mysteries (an example of “mystical fantasy”) from the Qidian platform.

If you haven’t read the more than 900 chapters that precede it, you might well feel confused by this scene.

Read more: Banned books behind bars

According to the author, though, even he couldn’t make sense of this chapter after it had been butchered by Qidian’s targeted censorship – entire chunks of the text having been removed inexplicably.

“Who’s going to understand this section of the plot with these parts removed?” he complained in a footnote under the chapter after it. “Not even I can understand it!”

The author was candid about his exasperation: “I can’t deal with my novel becoming inconsistent, structurally broken, and incoherent. It’s become random unintelligible nonsense… I can’t accept how perverted these revisions have become, to the point where the plot isn’t even coherent. I can’t even write clearly.”

Then, like so many other complaints about censorship behind the Great Firewall, the footnote disappeared – though not before it was archived by Taiwanese readers outside the wall, such as those on the CFantasy board of the PTT web forums.

And although the author later cooperated and rewrote the chapter to get around the censorship measures, this wasn’t enough to fix the choppiness of the plot, and distorted the overall tone of the story so it went from being mysterious and creepy to being a “buddy story,” according to one reader from Taiwan who I interviewed in person.

Vague Standards

Unfortunately, things haven’t been getting any better in 2023, said the same interviewee, who asked to go by the name “Daxiong.”

While Daxiong is free to say as he pleases in Taiwan, attributing such statements to him could put him at great risk if he ever flew to China – like human rights activist Li Minzhe, who was imprisoned for five years from 2017 to 2022 for “holding online political lectures and helping the families of jailed dissidents”, “demonstrating how Beijing’s harshest crackdown on human rights in decades has extended beyond China”, according to an article in the Taipei Times.

And just as before, the standards for censorship are frustratingly vague.

Violations were defined simply as “online literature problematic due to deviance, vulgarity, sexuality, and violence” in one interview with the head of China’s Sao Heng Da Fei Office, or SHDF (which translates to National Office Against Pornography and Illegal Publications).

Another press release on China News indicated obscene content is that which “is lewd or contains lewd material; sells sex and is unsuitable for circulation; advertises incorrect concepts of marriage and family morals; appeals to vulgar tastes, such as online satire and sarcasm; and that which advertises violence, gore, terror, cruelty, etc.”

But beyond blanket statements such as these, writers can often only guess what words or phrases might trigger the algorithms behind the censorship.

“There’s no telling what the ‘red line’ for online articles is, and it’s erratic,” one JJWXC.net author said in a recent report by The News Lens. “Sometimes it’s fine at the time, then a month later you’ll be told you’ve crossed this line out of nowhere and be asked to make changes, or the whole piece will just be deleted or locked.”

And the author of Lord of the Mysteries echoed similar sentiment when he speculated about his own case in 2019:

“We’re getting deleted for writing about bad people doing bad things and the ugliness of lashings? I didn’t even write about the sacrifice in detail, so it’s not like it could be imitated. I don’t understand these censorship standards at all. Are we supposed to just revise our books until they’re meaningless bullshit?”

Invisible Blacklists

In addition to the forms of censorship above, in which paragraphs disappear from books (or are flagged), or books are removed from platforms altogether, Daxiong and others have also observed a third form of censorship, in which individual words are starred out with asterisks.

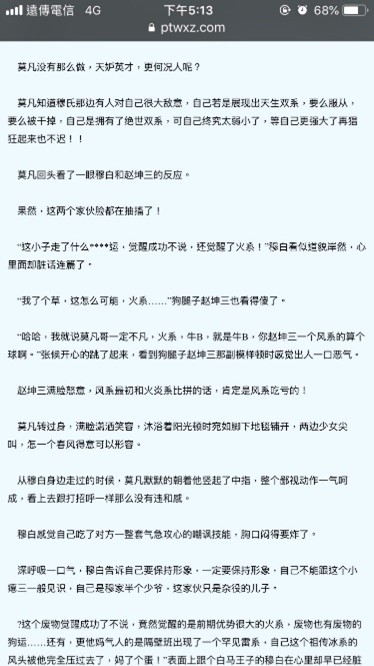

Daxiong showed me an example from a novel he had been reading on his phone – he didn’t have to look far to find it – “這小子走了什麼****運。” (“I don’t know what kind of **** luck this guy is having.”)

Screenshot of web novel censorship from Daxiong’s cell phone

He shrugged. “Dogshit good luck” would make sense in the context, but neither of us could be sure.

Unfortunately, the Chinese government doesn’t make its keyword blacklists public.

This is no surprise, as Daxiong told me there is something of an arms race between netizens and the government, as the former tries to get around censorship measures with increasingly obscure character combinations.

Sometimes, they use homophones – replacing characters with other characters that are pronounced the same. Other times, they do the opposite, and substitute characters that look similar but are pronounced differently.

The Latin alphabet is also used to skirt the rules, either by representing forbidden words in a full Romanized form – such as by writing out Xi Jinping in English, but with all lowercase and no spaces – or by shortening Romanizations into code-like acronyms – such as by shortening Xi Jinping to “xjp.”

He readily pointed to similar examples, some of which looked like swear words.

Still, the automated censorship could be sloppy even with these, such as when two halves of innocent words were mistakenly grouped together. For example, one netizen noted that the phrase for “an exchange of fire at a village entrance” (村口交戰) would get censored on Qidian because the middle two characters mean “oral sex” (口交) out of context.

And others couldn’t even be mistaken for obscenities. These are innocent words that have been banned not because of what they say explicitly, but because of sensitive topics they could implicitly refer to.

While we don’t know the exact word lists used for web novel censorship, in addition to piecing together clues from user feedback, we can also extrapolate from older blacklists that have been leaked.

The 2006-2009 Baidu search engine keyword blacklist leaked to Wikileaks, for example, is likely to have some cross-over with modern lists.

This list features innocuous words such as: “human rights protections” (人權保護) “brainwashing” (洗腦), and the decimal “6.4” – referring to the Tiananmen Square incident, known in Chinese as the six-four incident (June 4th incident). Slightly more overtly political terms include: “the nation of Taiwan” (台灣國), “don’t love the Party” (不愛黨) and “withdraw membership from the Party” (退黨).

Self-Censorship

Still, the matter is further complicated by the fact that content isn’t censored by a unified system, but platforms are instead pressured to either “self-censor” or face the consequences.

This is a daunting task for platforms like Qidian, which hosts over a million novels – often millions of characters long each – making for billions of characters’ worth of content to regulate.

If the “exchange of fire” example is any indication, they don’t seem to be up to the task either.

This is a fact the head of China’s SHDF seems to be aware of – and for which he fully blames the platforms.

“Some companies are overzealous and take a mechanical, cookie-cutter approach when asked to conform to clear censorship standards,” he said in the interview mentioned above. “This results in misunderstandings about regulation policies for people in the industry.”

Regardless of how clear these standards are made to such platforms, what is clear to everyone is that companies and individuals that don’t self-censor to the government’s satisfaction can face fines, be shut down for “reconsolidation,” and be put on “loss of trust blacklists” if they reoffend, as such penalties are regularly advertised by party media.

Backlash

Still, the SHDF head insists that China’s online community supports the new regulations for online fiction, as indicated by their proactiveness in reporting inappropriate content and problem companies (though this willingness can also be attributed to the money these whistleblowers are awarded for their efforts).

The SHDF announced that it had awarded over 1 million yuan RMB (about $150,000 USD) to whistleblowers for over 140,000 cases of violations from January to June of 2020, for example, including over 128,000 cases of “lewd/sexual information,” 5,502 cases of “illegal publishing/illegal religious publication,” 4,819 cases of “copyright infringement,” and 1,274 cases of “fake media, fake reporting, or fake reporter websites.”

As for those members of the public who are not onboard, the head of SHDF insists they are the victims of the intentional hyping of independent media outlets telling them certain groups are being oppressed, claiming: “[They] purposefully distort things to manipulate public opinion, making normal business regulation seem like it’s targeting [people].”

More telling is what he doesn’t say – that people may have valid concerns, or that there may be something his office or the government could be doing better.

Going Forward

Still, onboard or not, authors are increasingly involved in the self-censorship process, if only because they don’t want to see their works gutted or deleted as they’re posted.

Hands tied, these authors who haven’t disappeared – or been “404’d” – continue to struggle to express themselves.

In a way, they struggle in silence, as there’s only so much they can openly communicate. In another, their readers are with them, as they rely on a bond of mutual understanding to read between redacted lines.

“We notice things,” said Daxiong. “They have tricks for getting around the rules” – like innuendo and substitution words – “or they repost things that have just been deleted.”

As for Lord of the Mysteries, the novel continued to be serialized for another year until the plot concluded in 2020, even winning accolades domestically – though to this day no one can truly experience the author’s original vision for it.

In any event, it would seem the author was true to the final words of his 2019 footnote: “I’ll keep writing until I can’t write anymore – until I can’t bring myself to. I’m not going to punish my readers for someone else’s mistake. That’s that.”

Editor’s note: Sao Heng Da Fei (SHDF – the National Office Against Pornography and Illegal Publications) has not responded to requests for comment.

All artwork by Isabelle Broad.

Read more: