The new curator of the Screening Rights Film Festival, Misha Zakharov, explains how the festival has evolved, what the challenges are in producing an event like this, and how personal identities, histories and politics can enrich the film festival programme.

The Screening Rights Film Festival, now in its ninth year, was founded by Michele Aaron, Professor in Film and TV at the University of Warwick (then Senior Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Birmingham).

Initially held across various venues in Birmingham, in 2018 SRFF grew to encompass Coventry, with an online edition taking place in 2020.

Known for its diverse range of films about human rights and social justice issues—from historical atrocities to contemporary stories of activism—the festival aims to foster connections within and between communities, facilitate space for critical thinking, and provide tools for direct action.

All screenings at the festival are special events involving a post-screening expert-filled panel discussion on the topics raised. SRFF puts as much emphasis on the Q&As and audience participation as the films themselves.

This year, the festival’s theme is “The Dreams of Others”. It explores ideas of hope and despair, radical empathy and the necessity to truly listen, influenced by prominent artists and thinkers from bell hooks and Saidiya Hartman to James Baldwin and José Esteban Muñoz, from Maggie Nelson and Rebecca Solnit to Susan Sontag and Pauline Oliveiros. Here, the festival’s new curator, Misha Zakharov, Film and TV PhD candidate at Warwick University, explains the intricacies of curating and producing a human rights festival.

Organising SRFF 2023 is a part of my PhD project at Warwick which will be touching upon the ethics of film programming and film festivals as sites of learning, so it seems necessary to acknowledge my own positionality and relationality as well as to properly ground my identity. I identify as a Russian-born, male, queer person of Korean descent; an author, translator, film critic and curator; a fully-funded practice-as-research PhD student; and a political immigrant based in Coventry, UK.

Scene from the film “Ertak” shown at this year’s Screening Rights Film Festival “The Dreams of Other’s”

In March 2022, almost immediately in the wake of the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine, I left Russia to escape the political persecution on the basis of my pro-Ukrainian, anti-war stance; to evade the draft (which I’m eligible for as a male of conscription age) and taxes, so as not to fuel the military machine; and to flee the potential anti-LGBTQ+ crackdown, which I was certain would happen at some point (and it did, taking the form of the more severe anti-LGBTQ+ propaganda law introduced in Russia in December 2022).

Under no circumstances can I go back to Russia at the moment, which is why not only my funding and my stay in the UK, but also my safety depends on this PhD project, exacerbating the financial and legal precarity that international postgraduate students are facing with a political one.

Protests for solidarity with Ukraine in Manchester in March 2022. Picture by Ian Betley via Unsplash.

Not only is it the first-ever film festival I assembled largely on my own (from selecting the programme to negotiating with the venues and distributors to contributing programming notes and synopses to locating the after-screening panellists to engaging with local initiatives and communities to communicating with various administrative branches at Warwick), but it’s also one that I’ve made in an entirely new cultural and political context as well as within the financial infrastructure of an academic institution. It’s a huge undertaking, and I want to thank my supervisor and Screening Rights founder Michele Aaron for trusting me with the festival, and Pablo Alvarez Murillo for his invaluable contribution as a festival coordinator.

Ever since Harald Szeemann’s groundbreaking exhibition projects, there exists a modernist discourse of a curator as an author and even as an artist, the principal voice and the driving force behind the exhibition. This is in contrast with a postmodern idea of participatory art and a socially-engaged curator, who downplays their own involvement in the project, bringing the artist-audience relationship to the forefront. And this binary has been recently questioned on numerous occasions, most notably by Lynn Wray, who in her article “Taking a Position: Challenging the Anti-Authorial Turn in Art Curating“, borrowing from an artist and theorist Mieke Bal, proposes the idea of accountable curators completely in charge of their task, who see their exhibitions as arguments and “use [their symbolic power] as a means of political influence, rather than trying to neutralise their own privileged position”.

Read more: Nine human rights films not to be missed at this year’s Screening Rights Film Festival

In that view, being an activist film programmer would mean fully and responsibly embracing one’s own role while being self-critical of it; recognising one’s own agency while owning up to one’s mistakes; and adhering to certain principles in one’s programming, such as commitment to gender and ethnic diversity and the ecology of curating (giving voice to the oppressed, marginalised and underrepresented).

So, instead of concealing my biases, I’d like to focus on them to explain the programming choices and to also outline a few of the innumerable challenges that arise in the process of curating a social justice film festival.

My particular focus as a curator lies in queer and female-led cinema and collective filmmaking; the geographical area of Central and Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia; and the medium of the artists’ moving image. To select the films, I’ve been combing through the line-ups of other festivals, which included region-focused ones (GoEast), documentary film festivals (DocLisboa, CPH DOX, Sheffield Doc, Open City Doc, IDFA, Hot Docs, DOC NYC, DOK Leipzig), LGBTQ+ film festivals (Frameline, BFI Flare, Queer East), and human rights and activist film festivals (Human Rights Watch FF, Take One Action, FIFDH Geneve, Document FF). I always keep an eye out for the latest releases from certain distributors, such as Dogwoof and CAT&Docs, and online platforms like MUBI, Criterion Channel, BFI Player, Le Cinema Club, Shasha Movies and Another Screen. I was fortunate enough to issue my German visa to travel to this year’s Berlinale to watch as many social justice-related and specifically Ukrainian-led films as possible.

Scene from the film “A Night of Knowing Nothing” shown at this year’s Screening Rights Film Festival “The Dreams of Other’s”

On a personal note, my biggest concern was whether I was entitled to screen Ukrainian films as a Russian-born curator. This is an incredibly sensitive issue to tackle, and over-and-over I can see Western institutions making the same discursive misstep of inviting both sides for a supposed ‘dialogue’ or in an attempt to accommodate everyone, and then failing to mediate the situation.

Ideally we at SRFF should employ guest curators, something that has been done by my colleagues and fellow PhDs at Warwick at their Glasgow-based Eastern European film festival called Samizdat, but there’s no way we could afford this with the limited funding that we had. So, for me it was a choice of either curating the screening of a Ukrainian film myself, or not using an opportunity to platform Ukrainian voices at all, which is why I decided to go with it.

On every step, I sought advice from my Ukrainian friends, including other film curators, and from the Ukrainian institutions. By organising two screenings of Alisa Kovalenko’s We Will Not Fade Away at MAC and Warwick Arts Centre, we would first and foremost like to facilitate meeting points for the Ukrainian community in the Midlands.

The other challenge I’ve faced as a curator of an activist film festival is managing the political intensities of various communities.

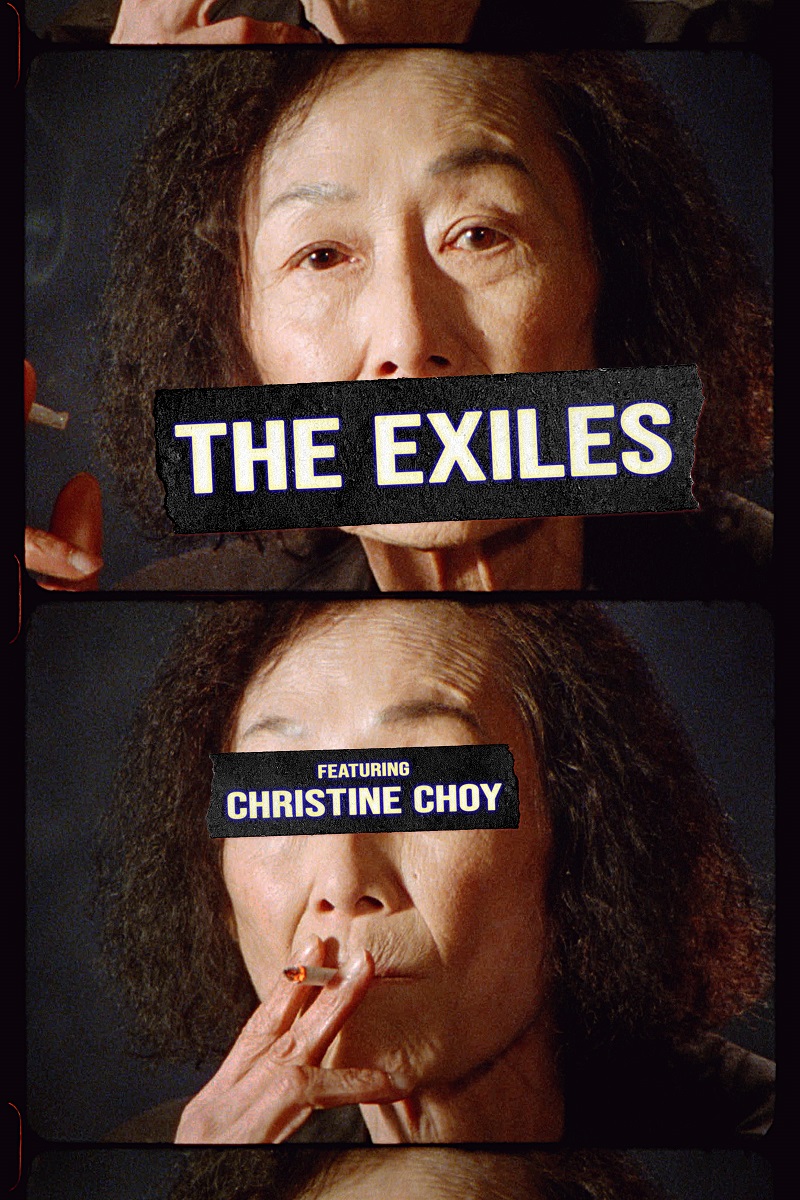

I was conscious that the Tiananmen Square massacre is an extremely sensitive issue for many Chinese people, but didn’t quite expect that we’d face refusal from certain Chinese communities in promoting one of the films from our programme, namely The Exiles, due to the divide that it might cause between the communities’ members. When asked about this, my friends from China and Taiwan explained that this timidity might be caused by the presence of the Chinese secret police in the UK, and also by the fact that many Chinese people, especially students, have to travel back to China. (It needs to be said that The Exiles is banned on the Chinese film-related social media network Douban.) Conversely, other audiences are mobilising against injustice, particularly the Palestinian/Arab, Armenian and Ukrainian communities, and we have to keep up with them.

Poster for the film “The Exiles”.

Curating a social justice film festival, especially a small-scale one, means to inevitably prioritise one human disaster over another. It also means that global politics will always affect the inner workings of the localised festival—sometimes in an unpredictable, disruptive, or devastatingly relevant way.

Due to the recent events, such as the escalation of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the occupation of Artsakh by the military forces of Azerbaijan, the attack on trans rights in the UK, and Russia’s ongoing war against Ukraine, films of the programme, which are urgent by themselves, have acquired an increased importance. But this also means that some of our speakers are now in grave danger or under a lot of stress, and obviously it rubs off on the festival team as well.

I would say that psychologically any curator of a human rights film festival operates under enormous emotional pressure, and there’s no easy remedy for this.

Over recent decades, the notion of human rights has become increasingly neoliberalised, and today ‘human rights cinema’ is a market as much as any other. Maintaining certain personal principles and integrity—such as refusing to collaborate with certain institutions—is therefore key for any curator. And then there is an issue of accommodating everyone—filmmakers, audiences, panellists—not only within a single screening, but across an entire festival, where different persons’ views might not necessarily correlate.

Social justice film festivals are difficult and messy (researcher Sonia Tascon calls them “sites of organised unruliness”), but maybe this is exactly what we need right now: agoras for public gatherings and discussion, where we can combat, disprove, or highlight certain things, and where four actors—the film, its audience, the invited panelists and the film programmers—can mutually educate each other.

Find the full Screening Rights programme here.

Read more:

- Nine human rights films not to be missed at this year’s Screening Rights Film Festival

- 12 Netflix documentaries and films to expand your worldview

- Short Film: Detention without walls

Main image by Photo by Felix Mooneeram on Unsplash.

Get involved

SRFF 2023 is looking for volunteers—film buffs, socially-engaged citizens, or both—in Birmingham, Coventry and the immediate vicinity, who could greet guests, redistribute flyers and questionnaires before and after screenings, lend a hand during the after-screening discussions, and provide some on-site photos and videos for the festival’s social media accounts. They are offering free tickets for festival screenings and can cover travel expenses. Email Misha Zakharov at misha.zakharov@warwick.ac.uk and Pablo Alvarez Murillo at pabloalvarezmurillo@gmail.com for more details.

In concurrence with this year’s programme, the festival is particularly keen on working with volunteers from the following backgrounds:

students

LGBTQ+ and more specifically trans persons

climate activists

contemporary art aficionados

Indian diasporas

Mainland Chinese, Taiwanese and Hong Kongese diasporas

Central Asian and more specifically Uzbekistani diasporas

Armenian diasporas

Arab and more specifically Palestinian diasporas

Ukrainian diasporas

and any other related communities.