The death in custody of 31-year-old Stefano Cucchi has brought the abuse of police power under scrutiny in Italy. After losing her brother and enduring the subsequent trial, Ilaria Cucchi is now receiving harassment and online threats from police officers. Sociologists say Stefano’s case is not isolated and ask what the country will do to clean up its policing.

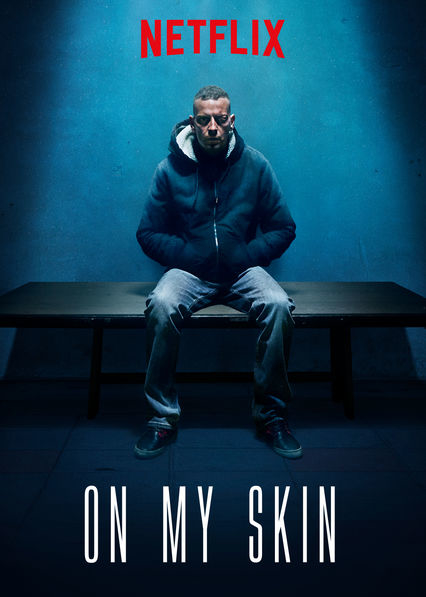

The Netflix film On My Skin (Sulla Mia Pelle), directed by Alessio Cremonini and starring Alessandro Borghi, premiered at the Venice Film Festival in August 2018.

At the end of the screening, Ilaria, a woman wearing a red dress, walked towards the film’s director, who was standing in the front row of the cinema receiving applause, and wrapped her arms around his neck.

The embrace momentarily hid their noticeably moved faces from the gaze of the surrounding crowd.

On My Skin (featured in our collection of human rights documentaries) tells the story of a man who was arrested by Carabinieri (Italy’s domestic police) officers in Rome and died in unclear circumstances after seven days of being in precautionary custody.

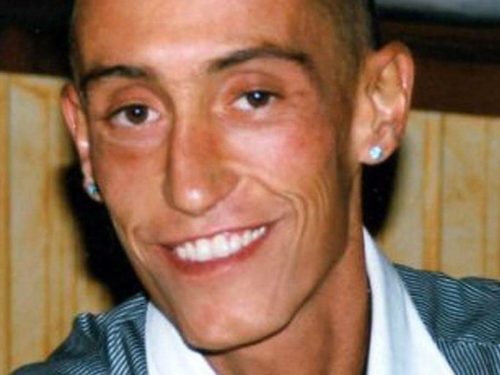

The man was Ilaria’s younger brother, Stefano Cucchi.

Since his death in 2009, Stefano, 31, has become an icon of the abuse of police power in Italy.

He was arrested on 15 October 2009, after being caught handing a dose of cannabis to his friend Emanuele Mancini.

He spent his first night in custody in a Carabinieri cell. The next day he was taken to a prison wing of the local general hospital with distinct marks and bruises on his eyes, back pain and injuries to his legs.

Seven days after his arrest, at 6.15am on 22 October, Stefano was found dead in his hospital bed.

This young amateur boxer was in good health before his arrest but his family obtained photographs from the morgue showing Stefano’s emaciated body covered in purple bruises. They rejected the assertion that Stefano had died of natural causes and began a campaign for justice.

A sister’s fight for justice

Stefano’s story sparked a debate about the abuse of police power at a national level. The case polarised the Italian public, as the story was heavily politicised and peppered with accusations, slander, threats and cover-ups.

Stefano’s sister Ilaria received support from many, but she also received criticism and scorn from those who believed the Carabinieri officers’ integrity and innocence.

However, this year – seven years after the first trial – one of the Carabinieri officers involved in the trial added a new twist to the story.

On My Skin (Sulla Mia Pelle) film poster

On 11 October 2018, Francesco Tedesco, one of the three indicted officers, confessed that Stefano had been beaten, accusing his two colleagues, Alessio di Bernardo and Raffaele D’Alessandro. Tedesco claimed he was only a witness to the abuse and tried to stop the other two officers as they beat him for refusing to cooperate.

Furthermore, he accused his superiors of forcing him to stay silent about what happened that night.

He claimed to have written a report about the beating, but said it was suppressed by his managers.

Seven years after the first trial, following 45 hearings, dozens of reports, investigations and more than 100 testimonies collected from witnesses, the second trial is still not concluded. The confession of Francesco Tedesco, however, could add a new direction.

Stefano’s sister Ilaria Cucchi hasn’t been alone in her battle as she has significant public support in fighting for justice.

Nevertheless, since the release of On My Skin, Ilaria has been receiving death threats on Facebook from supporters of the Northern League (one of Italy’s two co-ruling political parties) and from accounts she believes belong to police officers.

On 20 October 2018, Ilaria posted one such comment on Facebook, saying she feels that she and her loved ones (as well as lawyer Fabio Anselmo, who followed Stefano’s case from the beginning) are in danger.

Shining a light on police brutality in Italy

Anselmo’s law career spans some of the most renowed cases of abuse of power in Italy.

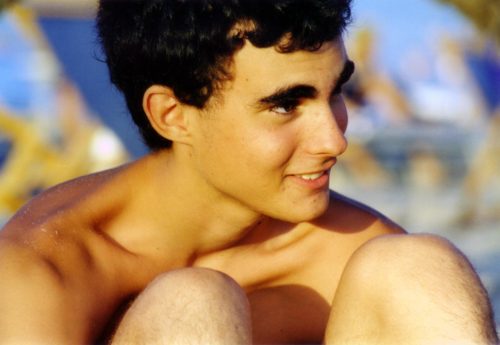

In 2005, he represented the family of 18-year-old Federico Aldrovandi, who was killed by four police officers when he was returning to his home in Ferrara. The trial ended in 2012 with the four officers sentenced to three years and six months each. This was later reduced by the Italian parliament to just six months each and the officers have now returned to work.

Lawyer Fabio Anselmo

Anselmo was also involved in the case of Giuseppe Uva, who died in unclear circumstances in 2008 while in police custody. The trial is ongoing.

These and other cases have brought to public opinion the concept of “morti di Stato” (deaths at the hands of the Italian State), a term which defines all those incidents of violent deaths in police custody and the corresponding abuse of power.

While the abuse of police power is not unusual in Italy, it’s not easy to obtain statistics or figures on the topic as the only available sources are the witnesses in the trials.

And while the stories of Stefano Cucchi, Federico Aldrovandi and Giuseppe Uva are the most well known among the Italian public, there are many more cases which have not yet had media coverage.

Federico Aldrovandi before his death

International organisations such as the UN and the EU have criticised Italian policing of certain events.

One of the most widely reported episodes in recent years of abuse of police power in Italy occurred in July 2001, during the 27th G8 summit hosted by Italy, in Genoa.

The two-day summit was attended by leaders of Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, the UK and the US. The summit drew 200,000 protesters from all over the world for a mass demonstration.

Between July 19 and 22, hundreds of demonstrators were involved in clashes with Italian police officers. Many were injured and 23-year-old Carlo Giuliani, was shot dead by officer Mario Placanica as he and other protesters attacked the officer’s van.

On 21st July, the day after Giuliani’s death, 250 police officers raided the Armando Diaz school with additional support from Carabinieri officers, beat demonstrators who were spending the night there. Police authorities justified the assault claiming that they were looking for black-bloc members (hard left protesters who wear black and obscure their faces) who had devastated part of the city of Genoa during the previous days of the summit. They arrested 93 people, but only one belonged to the black-bloc group. Nevertheless, 61 of them were taken to hospital with injuries.

In the same night, the police brought some of the activists and demonstrators arrested in the school to holding cells in the barracks of Bolzaneto, a suburb of Genoa. There, some of the officers tortured several people, mentally and physically, using humiliation, threats and beatings. They even forced some to exalt Fascism.

Amnesty International labelled the incidents during 2001’s G8 “the most serious suspension of democratic rights in a Western country since the Second World War”.

In 2015, The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) condemned Italy for the events, defining the violence committed by police officers as acts of torture. Later, Italy financially compensated 29 people who were beaten at Armando Diaz School and six who were tortured in the Bolzaneto barracks.

Italian laws fail to meet international standards

At an international level, Italy ratified the United Nations Convention against Torture in 1989, but did not introduce the convention into its legal system. In 2016, Ilaria Cucchi launched a petition on Change.org to introduce a law against torture. She gained more than 240,000 signatures. Eventually, Italy introduced the law in 2017, motivated by the verdicts of the ECHR.

However, according to the UN, as well as some experts and international human rights associations, the new law doesn’t respect international standards. As Human Rights Watch highlighted in their report, “the text of the new law requires ‘multiple acts’ for torture to occur. The [UN] convention, reflecting the international law, affirms ‘any act’ might be torture if it meets the gravity standard. The new law also requires that psychological trauma be ‘verifiable’ to establish ‘psychological’ torture”.

In the same report, Human Rights Watch said the discrepancy between the definition of torture drafted in the UN convention and the new law adopted by Italy (article 613-bis of the Penal Code) implies that “the restrictive definition and short statute of limitations – in a country whose judiciary system is infamous for its lengthy trials – raises the risks that torture will go unpunished, as well as hinder the ability of victims to get redress. This means that Italy will continue to be in violation of its international obligations.”.

Criticism about the new law, but for opposite reasons, came from some Italian right-wing movements too. On 12th July 2018, Fratelli D’Italia (Brothers of Italy) leader Giorgia Meloni announced on Twitter two proposals to abolish the crime of torture in Italy, on the grounds that the law would hinder the police officers to work properly. Her tweet has been widely criticised.

Two years before the introduction of the law, the current Deputy Prime Minister of Italy and Minister of the Interior Matteo Salvini criticised the verdict of the ECHR concerning the G8 in 2001 and said that a law against torture is a nonsense law that would allow criminals to blackmail police officers.

Could Cucchi’s case lead to improvements in policing?

Based at the University of Genoa, professor of sociology Salvatore Palidda is one of the few Italian researchers focusing on the relationship between police and civil society.

Stefano Cucchi before his death

According to Palidda, there are hundreds of cases like Cucchi’s, Aldrovandi’s and Uva’s that have not received media coverage, because they concern outcasts or immigrants without residency permits.

“The activity of police forces is always characterised by the coexistence of a peaceful management and a violent one. The discretion of power held by officers may turn into free will and lead to torture and murder”, Palidda said.

Key to understanding the violence perpetrated by some officers is their sense of impunity. “Some police managers tolerate and cover up illicit behaviours of officers in order to earn the respect of other subordinates and police trade unions,” Palidda explained.

Another factor that facilitates impunity is the reticence of police force members to report their colleagues. The stories of Aldrovandi, Cucchi and Uva, as well as the facts of the 2001 G8 in Genoa and many others are characterised by cover-ups and silence imposed by the officer’s superiors and colleagues. Indeed, the unexpected confession of the Carabinieri officer Francesco Tedesco regarding the death of Stefano Cucchi is a rare breach of this convention.

Palidda says one practical method of containing and controlling police brutality in Italy is to “establish an independent authority that would monitor and regulate the activities of police forces. This should bring impunity to an end and tribunals would investigate the alleged crimes without the support of police”.

However, he added, “these measures are possible only in a country where most of the population has an effective sense of democracy”.

- For stories like this direct to your inbox, subscribe here. Or follow us on Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.