In Ethiopia a sense of hopelessness hangs over refugee camps where hundreds of thousands of people are left waiting to build new lives. Lacuna’s writer-in-residence, Rebecca Omonira-Oyekanmi, meets those who have fled home but are yet to find sanctuary, and sees how art and performance are helping them heal.

Find part 1 and part 2 here.

Within 12 months of arriving at the Adi Harush refugee camp Nakfa, 19, had completed courses in traditional Eritrean dance, singing, youth work and computer studies. She wrote poems protesting sexual violence against women and songs about her home town, Asmara. When the Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) built a suite of classrooms to house a library and host art, music and dance lessons, Nakfa would spend all her time there. After she graduated from her own classes, she assisted with dance classes for the younger refugees. Nakfa’s anxiety rose as the opportunities to stay busy dwindled. She feared the time when there was nothing to do but wait.

Around her, other refugees waited, stuck in the unending time between fleeing home and finding sanctuary. The border crossed, story told, refugee status awarded, temporary hut secured, then the wait. Days became weeks, weeks turned into months. One year, two years, three years. “There are girls and boys like me who stay six years long here, who haven’t had any success for resettlement. I fear becoming like them,” said Nakfa.

***

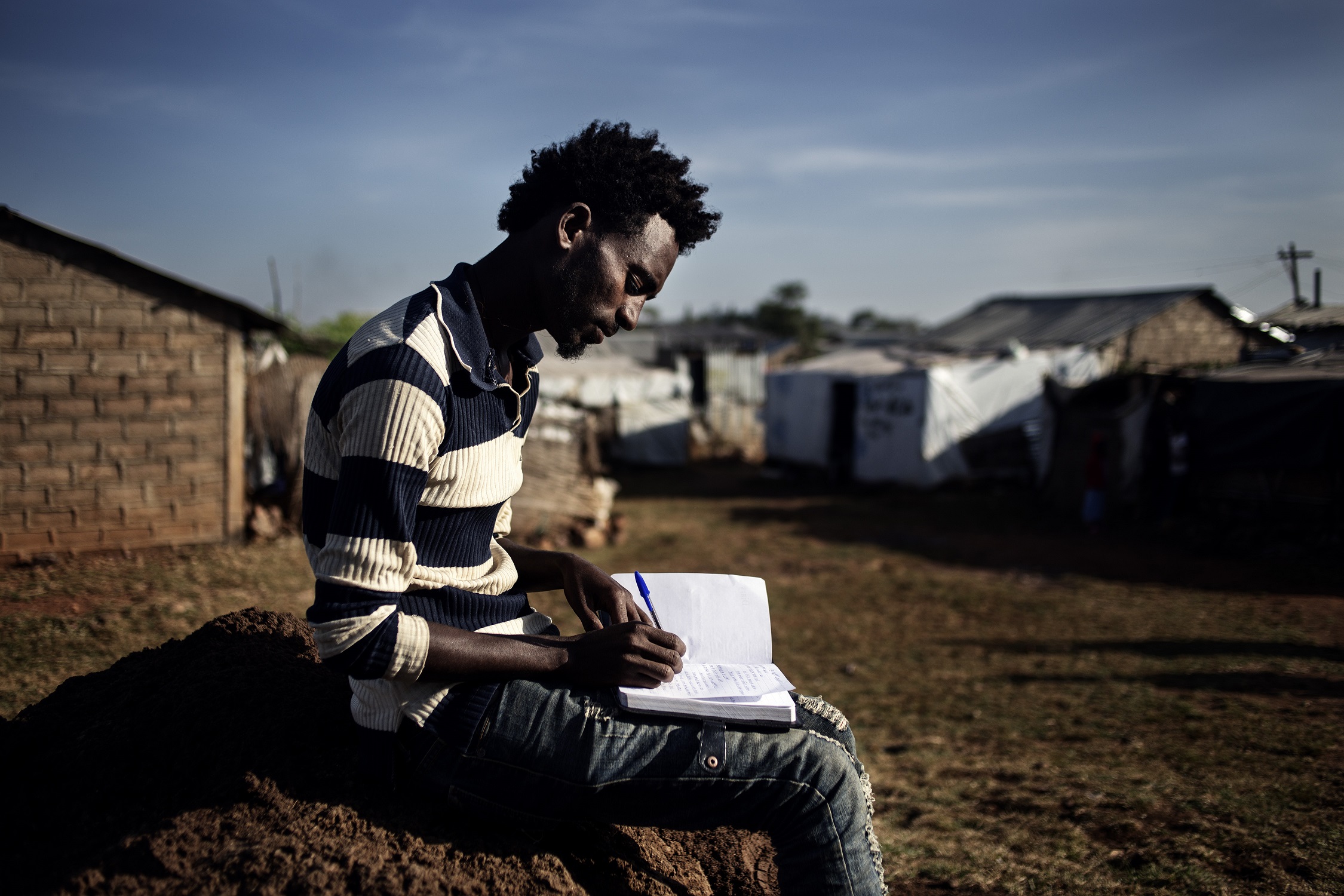

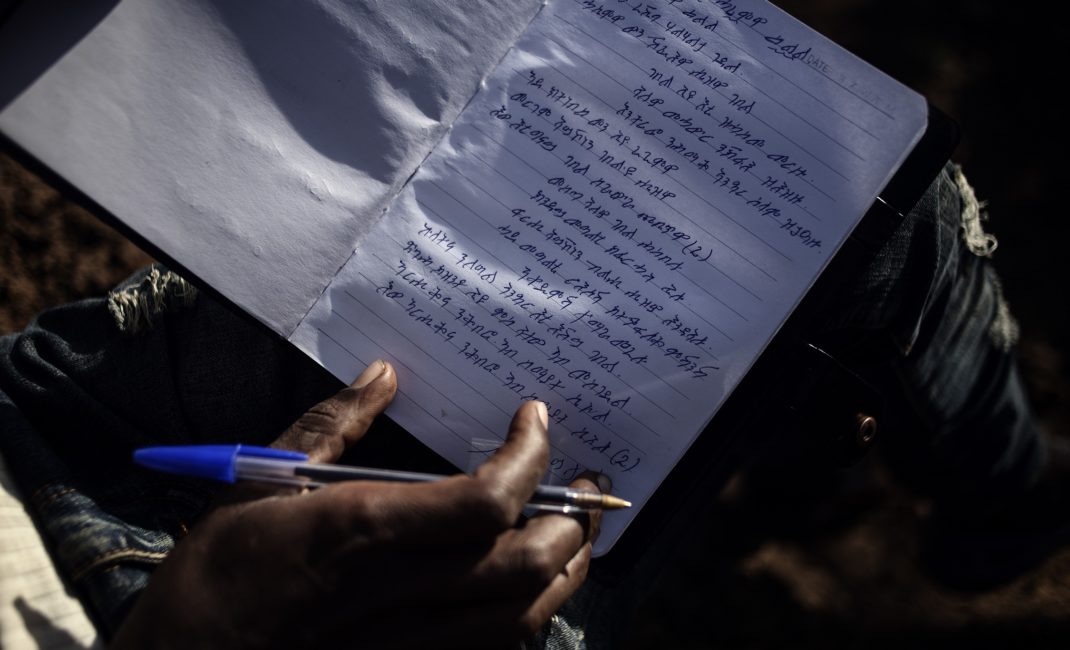

Tesfaye, a friend of Nakfa’s, describes this feeling of hopelessness in a poem he has written in between classes at JRS. The 24-year-old scribbles in a thick blue notebook, the story of his life “written in sheets of papers”. The poem is about the lack of Ele, he says. He makes a high pitched sound, rolling his tongue and raising his head. The “Ele” is a long ululation cry of happiness. “My country is desperate of getting [he ululates]. My mother is desperate of getting Ele.”

In sleep Tesfaye is haunted by all that has happened since he last saw his mother in Eritrea. He finds some relief in writing and telling stories of home. “Sometimes when in grief you can write about it. When you do this, you are writing life.”

Storytelling, whether through poetry, song or drama, is an important part of life among Nakfa’s group of friends at the camp. Most days they leave their huts and follow a dirt track busy with children playing, women carrying loads, herds of scrawny cows and occasional signs (Let’s Join Together to end violence against women!). After a mile or so the track dips into a rocky stream and up again to an open expanse of green and yellow grasses against a mountainous backdrop.

Gabriel Pecot for ODI

Adi Harush is found in the mountainous Tigray region of northern Ethiopia. It is one of four camps in the Shire district, home to predominantly Eritrean refugees of Tigrinya ethnicity. The day I arrive, Nakfa, wearing a ripped jean waistcoat, over pastel blue T-shirt with “JRS” written across it, dances between a drama rehearsal and a music session. She is one of the youngest musicians there in the jamming session. The others, a group of Eritrean men in their twenties and older, play guitar, keyboard, drums and an array of traditional instruments. Nakfa’s high pitched voice strains over the boom of Eritrean folk music. In another room, teenagers gather to rehearse a play Tesfaye has written.

The makeshift studio is part of the JRS suite of classrooms built recently on this open expanse, away from the huts, shacks and community buildings that make up the camp. Drama, art and music classes take place daily, attended mostly by children and teenagers. There is a library where Kibrom finds comfort in Eritrean history books and a space for outdoor sports. The classes are the brainchild of the Jesuit Refugee Service, which employs social workers and artists to work with the children and young people in the camp. Their staff work across several camps in the Shire region and employ refugees with the right skills as apprentice teachers.

In the bright classroom next door to the music studio, Nakfa helps her friend Freweyni teach small children to dance and sing in Tigrinya. Aged between nine and 12 they are all Eritrean and have experienced varying levels of trauma.

Having fled their homes with their families, they are now stuck in the camp, some have lived there for years. The children dance on Mondays and Wednesdays. For special shows they wear white sheets over their jeans and T-shirts.

Gabriel Pecot for ODI

Botel is 12 and has lived in the camp for five years. She learned Tigrinya dancing in Adi Harush, it’s her favourite subject. Glued to her side was Sale, a small nine-year-old with a wide smile. Botel is deaf and Sale was one of the few people who could communicate with her. Whenever Botel spoke, Sale turned to her and looked up at her face, hands flying, before turning to relay their thoughts. Zoweed, 10, was the best dancer and often led the group during performances. Before her family arrived in Ethiopia, she thought they were travelling to a big city, like Addis Ababa or somewhere outside Africa. “Then we came here and it’s not so big,” she says, smiling shyly. “We thought our life would be better.”

One young Eritrean man, a teacher, waited five years in Adi Harush. He applied to the UN for resettlement, along with hundreds of thousands of refugees like him living in Ethiopia. Of almost 800,000 refugees in Ethiopia last year, around 6,500 were placed on the resettlement waiting list. The resettlement process itself can take years. In 2015 there were 5,965 people on the resettlement list and just 3,818 departures. The US took 3,543 people, Canada 180, Australia 82, Netherlands 6, Sweden 5, Norway 2.

“Resettlement doesn’t mean movement. It takes an average of three years,” said a senior official involved in refugee administration and policy in Ethiopia. We met in Addis Ababa where he gave a long-ranging interview which he insisted be off record, sensitive to the implications of critiquing the process. But what he said is an open secret. Resettlement is a lottery, dependent on the political mood of richer nations in the West, bureaucracy, and in some cases, knowing the right people.

“It is not perfect, but we try,” he said, later adding: “Resettlement is not a right.” It’s a sentiment I would hear again from government officials, charity workers and refugees themselves.

The young Eritrean teacher placed his faith in the process and waited for resettlement. But for five years nothing happened. Tired of waiting, he left Ethiopia. He took the irregular route, crossing the border into Sudan. He made it as far as Libya, where he was caught in the crossfire of the civil war and killed. Back in Ethiopia his resettlement papers arrived too late.

***

The teacher’s story was one of many I heard at Adi Harush, where people gave me different population figures for the camp ranging from 8,000 to more than 30,000.

In 2015, the UNHCR, the Ethiopian government and the World Food Program conducted a counting exercise across the four Shire camps and discovered only 33,115 refugees were regularly collecting their food ration cards. At the time, more than 100,000 refugees were officially registered to receive the cards. Many of the ‘missing’ refugees had left the camp and moved to cities across Ethiopia or left the country.

The food ration cards provide each refugee with monthly rations. Nakfa told me she receives 10kg of wheat flour, 1 litre of oil, 1kg of lentils and 60 Ethiopian Birr cash (roughly £2). “The 60 Birr is not enough to purchase other food items, only 1kg of tomato and oil. It is too small. But for other people, they have assistance from abroad. It is difficult for anyone to survive on this alone,” she said.

Gabriel Pecot for ODI

The mobility of an increasingly youthful population, unwilling to spend years living in camps, is partly why it’s difficult to keep track of how many refugees live here. Toward the end of 2015 and early 2016 the Danish Refugee Council conducted extensive research across Ethiopia into the onward movement of refugees in the country. It discovered that in Adi Harush 54% of the population were aged between 19 and 25. In neighbouring Hitsats camp, 69% were aged between 16 and 25,. And the young are constantly moving. Some live undocumented in Ethiopia’s cities, others leave. Europe is one of many destinations. If there are opportunities in South Africa or Sudan, they go there. Or to countries in the Gulf, Yemen or Israel, all dependent on civil unrest, conflict, availability of work and the presence of a diaspora. Across the four Shire camps there were on average 300 to 400 unaccompanied minors arriving each month, and 250 leaving.

The Danish Refugee Council research revealed that “almost 40% of Eritrean refugees leave the camps within the first three months of arrival to Ethiopia and 80% leave in the first year of arrival.”

Reasons for quick flight vary: lack of work or opportunities for education, pressure from family outside Ethiopia. Ethiopia grants refugee status to nearly all asylum seekers, but restricts their movement within the country. This means you could be stuck in a camp for years waiting for resettlement. Camps like Adi Harush are in rural areas with pockets of poverty and few opportunities for newcomers to find work. Back in Addis, I interviewed two researchers who worked on the Danish Refugee Council report. They categorised the reasons for people leaving as lack of employment, lack of education and lack of integration. The harder to quantify finding was the general feeling of hopelessness.

***

Zoweed, Tesfaye, Nakfa, and the other children aren’t permitted to leave the camp. Though the Ethiopian government bestows refugee status on nearly all asylum seekers arriving in the country, it severely restricts their movement and access to the labour market. Refugees cannot leave designated camps, which are mostly spread along the country’s borders, unless they have serious medical requirements, are vulnerable to exploitation within the camps or are waiting to be resettled.

Gabriel Pecot for ODI

All this might change. As part of efforts to stem the flow of people crossing the Mediterranean, European governments have offered Ethiopia millions in aid. In return, the Ethiopian government has promised to ease movement restrictions and open the job market to refugees. The timeline for this process is uncertain. The Ethiopian government has only just lifted a 10-month state of emergency which placed certain restrictions on Ethiopian citizens. It is uncertain what this means for freedom of movement for refugees.

Meanwhile in Adi Harush refugees are under curfew because of hostility from nearby locals. Poverty outside the camp is strikingly similar to that inside it, and some locals resent the support being given to the refugees. A few NGOs work around this by providing essentials like clean water tanks to both refugees and local Ethiopians. Relations are said to be improving but refugees are prevented from leaving the camp after 7pm.

***

Nakfa is too poor to take advantage of the out-of-camp policy for Eritreans and travel to Addis, the place she is mostly likely to earn money. There are rumours that Eritrean girls are trafficked from the camps to Addis for sex work, while others can earn a living as musicians performing at weddings and in clubs. Refugees aren’t legally allowed to work, but unofficially the government is relaxed about Eritreans working as musicians or for charities within the refugee sector. This is something Tolde, a JRS social worker and teacher working in Adi Harush encourages his most talented students to consider. Music can be a way of surviving, he says.

Gabriel Pecot for ODI

He recalled one Eritrean refugee in his early twenties who had made some attempts to get to Europe, but found himself back in Ethiopia and at Adi Harush. He joined the music classes at JRS and looked set to stay put. Tolde was bowled over by his natural talent: “His work is amazing. He can create lyrics and melody immediately. He is an actor, a stand-up comedian. We all laughed when he performed.” But in the spring of 2016, the young man set off again and this time made it to Italy. “He wanted to stay here,” Tolde says sadly, “I was pushing for him to work on an album or a movie, to sell. But his family was pushing him to go again. He needs to help his family. They said, ‘You have to go. There is no way to make money here’. He needed money so he went to Italy.”

For the younger refugees left behind, music is a salve. “Most of them I would say, they are depressed,” says Tolde.

Every week there are stories of people leaving for Europe, stories of people killed in Libya, people dead at sea. Some of the younger refugees in the camp self-medicate with alcohol. Last year two girls killed themselves. Suicide attempts are not uncommon. The classes provide some relief, they can take a break from these pressures. The idea of the classes is to achieve a kind of therapy, even counselling, through performing arts and storytelling. Tolde has worked across Africa and Europe as a producer, contemporary dance teacher and therapist, and is writing a second book about the role of the arts in therapy and counselling. Infused in every lesson are the cultural traditions of the Tigrinya people, an especial draw to the younger refugees, many having left behind difficult home lives. It offers a more positive narrative about home. “I love remembering the culture of our people,” says Nakfa. “The culture of our grandparents is our inheritance.”

Gabriel Pecot for ODI

I watch Tolde’s class of teenagers and twentysomethings rehearse Tesfaye’s drama sketch. Asmelash, who was an actor and playwright in Eritrea, runs the rehearsal sessions. He is 32 and has lived in the camp for nearly three years. He keeps a picture of himself from his acting days in his back pocket. It was taken less than a decade ago, he has full cheeks, thick hair and bright eyes. In the intervening years Asmelash was tortured and imprisoned for two years by the Eritrean government for writing a subversive play. Then he was tortured as he tried to get to Europe – three times in fact, in Sudan, in Libya and in Egypt. All this sits on his person like a cloak.

He is visibly thinner, his cheeks hollow and his large eyes resigned. But when he is teaching, something of the man in the photo is kindled.

“The major thing that makes me happy is that the students have passion like me. During the weekends I feel stressed, until JRS opens.”

Gabriel Pecot for ODI

Asmelash begins his class with physical exercises. The students breathe, shout and stretch. “It is important because they are tired, their spirits are tired. It helps them relax their body and mind,” he says. Once the children are relaxed, they immerse themselves in creating art. The scripts they write, their music and their improvisation becomes a way of telling their own stories. Nakfa’s folksy songs of lament for Asmara. Kibrom’s poems of a poverty-stricken land, sang to the strains of a krar, a wooden guitar used by Eritrean and Ethiopian musicians. “They explain their lives naturally. What they feel, how they survive. They explain in music and lyrics and drama,” says Tolde.

Gabriel Pecot for ODI

They have been working on the drama sketch for two months. The objective, says Asmelash, is to reflect elements of traditional Eritrean storytelling as practiced in rural areas.

Rehearsals are cramped, taking place in one of the JRS classrooms. Chairs and tables are pushed to one side, and a gaggle of teenagers, or the chorus, slouch against the walls while scenes are acted out in the centre of the room. The play opens with a comedic exchange between two teenage boys leaning on shepherd crooks. Tesfaye, the lovesick lead character, enters and the scene becomes farcical. He hops and jumps, much to the delight of the chorus, as one of the shepherds tries to beat him.

***

Off stage Tesfaye is shy, far removed from the Romeo he plays, always scribbling in his notebook. The book was a recent purchase, for short stories, poems and scripts. Like Asmelash and Nakfa, for Tesfaye the drama classes provide a respite from the nightmare of his past. “When I come to the JRS centre I feel good. My mind is rested.”

Gabriel Pecot for ODI

Parts of his story echo Nakfa’s experience. Tesfaye was drafted into the army in Eritrea when he was just 15. He spent four years in the army and during this time saw his family just once. Aged 19 he fled the country and crossed the Marab River into Ethiopia. Free but poor and without connections, Tesfaye lived in a tent on a refugee camp for a year working odd jobs on the black market till he had enough money to leave. It was a lonely and isolated existence. “I felt stressed. I said to myself, ‘Who is going to help me?”’

Tesfaye saved 2,000 Birr (about £70), which covered part of his passage to Sudan.

“As soon as I went to Sudan I was kidnapped … I had no idea where I was. Then I was taken to the Sinai desert.”

He was tortured for three months: up and down his legs the skin remains charred. They used electric shocks and burning rubber as weapons. “They also hung me upside down, they tied my hands. The perpetrators wore blindfolds, veils in order to avoid being recognised. They beat me.” The kidnappers called his mother and demanded money or they would kill him. “But 11 years ago my father passed away, my mother has no money. But she raised the money.

Gabriel Pecot for ODI

She asked other people,” Tesfaye said. “As soon as I was released I couldn’t walk. My leg was paralysed. Then from Sinai we paced the desert and by foot we went to the Israel border and they dumped us there.” The terror continued as he was passed from Israel to Egypt and imprisoned for another four months, in a basement with no light. Then there were spells in prison in Cairo, threats and bribes. Eventually when he couldn’t pay anymore he was deported back to Eritrea. As punishment for leaving the country he was imprisoned where the torture and beatings continued. One day, during a mass escape from the prison he was being held at, four Eritrean prisoners were shot and killed by guards. Tesfaye escaped unharmed and made his way to Ethiopia.

That was two years ago. Tesfaye still dreams of going to school, but as far as he is aware he’ll have to leave Ethiopia for that. He has no intention of trying the irregular route again, despite applying for resettlement and hearing nothing back. “I will wait for the legal process because I know the situation. I have injuries on my body and I cannot go this way again.” Living in Adi Harush and seeing people leave every week can trigger nightmares of his own trip. Two of his friends took the same route he did; one made it to Germany and the other drowned in the Mediterranean Sea.

_______________________________________________________

Read more:

MORE FROM ETHIOPIA: