More than 500 refugees have drowned in the Mediterranean Sea this year raising fears that this could be the deadliest yet in Europe. Politicians have responded by tightening EU border security and outsourcing controls to third countries. Meanwhile refugees continue to move. In this three-part series, Rebecca Omonira-Oyekanmi tells the stories of people risking their lives to reach Europe and the factors affecting their decision making.

When I first met Nakfa she didn’t mention her trip to Sudan or what happened to her there.

We sat side by side watching a play in a small classroom in a refugee camp in northern Ethiopia. She was 19 but trying to look older: curly hair piled high on her head, a smudge of dark pink lipstick and an air of certainty and confidence.

I was reporting at the camp alongside the photojournalist Gabriel Pecot. We’d been commissioned by two experts on migration from the Overseas Development Institute (ODI). The ODI had its own team of researchers working on an official report, but what they wanted from us were stories and the human realities of what life was like for Eritrean refugees living in Ethiopia. Both Gabriel and I had covered different aspects of the European refugee crisis in recent years, and shared a desire to delve deeper into the lives of the people arriving on Europe’s shores.

This was back in November when the narrative around the refugee crisis had long since shifted. While there were still pockets of sympathy for the plight of refugees in Europe, the popular press had reverted to vilifying them. They drew links between terrorist attacks and refugee arrivals, and questioned the veracity of asylum claims. Meanwhile, the fall in refugee numbers in 2016 made it easier for policy makers to look away even though the symptoms of the original crisis remained. Refugees and migrants arriving in Europe by sea fell from more than one million in 2015 to around 360,000 in 2016. In one of its regular press notes Frontex, the EU’s border police, attributed this to deal the Union agreed with Turkey last March. A deal widely condemned as unlawful.

Of the more than one million arrivals in 2015, a little over 800,000 came via the eastern Mediterranean. These refugees are now blocked by the Turkey deal: that number dropped to 173,450 in 2016. Over in the central Mediterranean, the number of people arriving from North Africa rose, from 153,842 to 181,436. And this group, from Africa, accounted for many of the deaths at sea last year, which jumped to 5,082.

This all matters because policy-makers continue to look away from the structural, global symptoms causing people to move. They look only at the numbers. In February, European Union leaders signed a deal with Libya, echoing the pact made with Turkey last year. In return for millions in aid, Libya will beef up its border security and stem the flow of people crossing the Mediterranean Sea. Again, this deal has been widely condemned. The horrors of life in Libya for migrants are well documented. But still the compromises continue. The deaths of people trying to get to Europe, will simply be pushed back, away from our beaches, the dying will occur out of sight.

But what if we knew more about the hundreds of thousands who arrive in Europe? Something of their inner-lives before they even make the decision to leave Africa, the fantastical, dangerous aspects of their reality and the mundane, the everyday things that affect them. What if we listened to the tapestry of stories lost in the deals and politics? This is what I went to find out in Ethiopia.

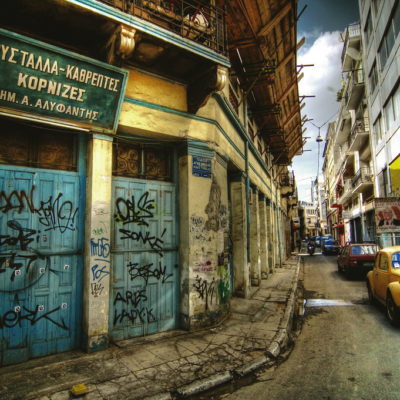

Searching for stories: sunrise on the Adi Harsh refugee camp

Nakfa told me her story over several days. We chatted first, casually as she went about her day, before sitting down for a formal interview, filmed by Gabriel. The next day, I followed Nakfa to a friend’s house, where she babysat and prepared lunch while her friend cleaned the hut. And we talked some more about her family and about Eritrea, her home country, and life in the camp. After some time, a shy teenager looked in. He was thin, shorter than Nakfa, with darker skin and thick eyelashes. ‘This is the one I told you about,’ Nakfa said. His name was Kibrom and they’d crossed the border from Eritrea together.

Later I interviewed Kibrom too, in the one-room concrete hut he shared with Nakfa and another girl, Tewen. (Tewen wanted to share her story as well, but I was evicted from the camp by officials before I could speak to her.) Their room was dark, but the late afternoon sun provided a sliver of light through the doorway. Nakfa knelt in front of a portable stove and roasted a pan of coffee beans. We talked for an hour. Kibrom told me about the route people took through Sudan and the costs that would incur.

At one point Nakfa interjected. She had been bustling in the background, conducting the elaborate coffee ceremony both Ethiopians and Eritreans perform several times a day. Greenish beans are roasted, ground and strained into hot water, transferred to a special jug, and poured slowly into tiny cups full of sugar.

New generation: Nakfa using her smart phone to show us a Facebook video.

Nakfa looked up. “I myself went to Sudan in 2012. I was burnt by fire,” she said in English. Then, switching to Tigrinya, she stood up, lifted her leg and pointed at the skin on her calf. “I was stabbed. They boiled an iron rod and burned my leg.” Her expression blank, she twisted her body and lifted her shorts revealing more thick slabs of blackened skin.

Our first interview had been harrowing, she had been in floods of tears. But here was yet more trauma that she’d kept hidden. “I didn’t think you were interested in that,” she said when I asked why she hadn’t mentioned it. The translator wondered if she’d told UNHCR, it might help her chances of resettlement. She shook her head. Nakfa had kept quiet during her screening interview when she’d first arrived in Ethiopia.

But that was months ago. The dream of resettlement had dwindled and Nakfa was less fearful of the official process. We agreed to another interview, later, but for the moment we continued with Kibrom’s story and she went back to making us coffee.

Part 2 – Nakfa’s story

Banner photo by Gabriel Pecot©