More than 500 refugees have drowned in the Mediterranean Sea this year raising fears that this could be the deadliest yet in Europe. Politicians have responded by tightening EU border security and outsourcing controls to third countries. Meanwhile refugees continue to move. In this three-part series from Ethiopia, Rebecca Omonira-Oyekanmi tells the stories of people risking their lives to reach Europe and the factors affecting their decision making. Photos and film by Gabriel Pecot.

Find the first part of the story here.

Nakfa was 15 when she first left Eritrea.

Leaving the country under cover of darkness was something like a rite of passage at her secondary school in Asmara. The year Nakfa ran away around half a dozen of her classmates were leaving each month. Sometimes in groups and sometimes alone they would cross the northern border into Sudan. Nakfa left with two friends. It was a snap decision with little planning. “One of my friends, Solyen, got 100 Nakfa [about £5] from her home to buy transportation tickets. We headed to Tesseney in the footsteps of the other children. We didn’t tell anyone.”

In Tesseney they caught a bus to Mekeserat, a small village on the northern border with Sudan. Nakfa had never travelled this far from home and immediately she was struck by the pale skinned northerners with their “Arabic look”. Up till then she imagined that hers – soft brown hue, round cheeks, loose curly hair – was the look of Eritrea. “We saw their faces, different to us, we felt excited,” she said. “We had never seen such people and we assumed we’d entered a different country.” The trio stopped at a cafe for bread and tea, and gawped at what were likely members of Eritrea’s Rashaida tribe.

An elderly woman selling coffee spotted the outsiders and beckoned them. “If you would like to cross the border, you need to veil your faces and wear the full dress otherwise you will be taken by smugglers,” she said, passing them a bag of black cloth. “You are still in Eritrean soil and not in Sudan. If you want to cross the border, you will have to pass through vegetation, banana and orange plantations. Pretend to be fruit pickers and then cross.”

The teenagers had been walking for some time when they saw a man approach. “As-salaam ‘alaykum,” he said. The man carried a “big knife” and a “pistol”. A veil covered most of his face. “Because we watched films, we knew how to respond,” says Nakfa. “We said, ‘Alaykum salaam.’”

The man replied: “Do you speak Arabic?”

Confused and scared, Nakfa and her friends shook their heads. “So he took us. He said, “OK let’s go.’” They followed him into the forest.

Nakfa wants to go to Europe from the Horn of Africa and her only option is on foot.

She knows people that have travelled this way. She has relatives whom she knows have been tortured and killed on route. And she has neighbours who have drowned as they attempted to cross the Mediterranean Sea, the deadly finale for refugees and migrants without papers on their way to Europe. Last year 4,579 people drowned trying to cross the sea from Libya, including around 700 children. Hundreds of thousands with dreams like Nakfa’s remain trapped in Libya.

Death is not the only risk. Children are especially vulnerable to a myriad of evils. UNICEF collected the testimony of thousands of children in a new report, a violent tale of kidnap, rape and torture as they make their way across Africa to Libya and Europe.

Nakfa didn’t make it as far as Libya. She and her friends followed the mysterious man into a forest to a house made of tin sheets. “He put us there. There were many girls and boys kept nearby. We were kept in different cells.” Nakfa’s biggest fear was sexual assault. “This is a known fact, every Eritrean knows this. For women sexual assault is common. Kidnap is common.”

Increasingly international governments, journalists and NGOs working closely with refugees across Africa and Europe know this too. Nakfa was at the start of what is known as the “Sinai Trafficking” route, a gruesome trail of exploitation and murder. It is estimated that some 5,000 to 10,000 people die in the Sinai Peninsula, on their way to the northern shores of Africa.

The other captured children Nakfa saw were Eritrean too, and she soon discovered why they – and she – had been kidnapped. “The smugglers asked me for my phone number. I said no because in my home country I knew that there was a relative who experienced these difficulties. I wanted to avoid bothering my parents,” she said. “Of course, I knew my home number, but I said I didn’t know. Then he beat me.” The man began to shout: Tell me the truth! Tell me the truth! He wanted Nakfa to call her parents so that he could demand a ransom. When she refused, he beat her.

The evidence of her ordeal is a forest of darkened scars on her calves and thighs. One of the shrivelled patches of skin is shaped like the three prongs of a small fork. A knife, hot rod and a fork dipped into hot oil and pressed on to her skin. “My leg was swollen, liquid was coming out, it was very big. They couldn’t… I wasn’t telling them everything.”

Four years separate Nakfa from that night and she is matter of fact as she wields a knife and fork to explain what happened. Torture was always a possibility, she says, perhaps in hindsight: “I knew they were doing such things. I have a cousin who was held by the smugglers. He was very burnt with so many iron rods. He was released. I paid him a visit, he showed us the wounds. He died in Asmara hospital.”

Nakfa explains what happened in Sudan

Time disappeared. Nakfa heard the screams of others, someone locked a door, she was in a room with adults and children now, they were left alone. Her friend Solyen was with her again and had fallen asleep, but now and then she would wake up, screaming. Perhaps the noise bothered him or maybe he needed the room for the latest cohort of unfortunate travellers, but Nakfa says her kidnapper eventually let them go. “He opened the door and let us out. We were five in total.” The others had been held longer than Nakfa, more than a month in their darkened prison, and they winced when they were let out into the daylight. They were all sent back across the border and warned to stay quiet.

When they reached Eritrea they were taken to a military base where the adults were held by soldiers and the children were scolded and then sent home.

Nakfa returned to school and stayed until she was 16.

Following her 16th birthday, she joined the Eritrean army. It wasn’t by choice. Every Eritrean schoolchild is obliged to complete their final year of secondary education in a special school cum military base known as Sawa, where they undergo physical training alongside academic study.

During the brief years of peace after independence in 1991 and before the border war with Ethiopia in 1998, Eritrean leaders devised a governance strategy that put military service at the heart of a new Eritrea. The spirit of the liberation movement would live on. Men and women would serve together, everyone between the ages of 18 and 50. Training would begin at school, with few exceptions. The slogan oft heard was, No war, no peace. Life in the army was tough, especially if you were a young woman. Sexual assault was common. The most extreme cases were documented in the UN’s report from its special inquiry into human rights abuses in Eritrea.

Recruits worked a 12-hour day, starting at dawn with a long run. Much army work was construction, agricultural and mining. Food rations consisted of one or two meals of watery lentils, stale bread and tea. There were no wages until the first year of training was completed, even then it depended on the whim of senior officers. And military service can last years. There are Eritreans who have served since the mid-90s with no prospect of release.

Nakfa hated army life. She served one year and performed poorly in her final exams, and after a brief period at home she was recalled back to serve. But for two months, Nakfa ignored the summons.

***

Nakfa is the eldest child of eight and she needed to find paid work. It wasn’t clear whether she would be paid in the army. Her father had died when she was 13 and there were no relatives abroad to support the family. Nakfa’s family had moved from their home in Adi Quala to the capital Asmara because her mother hoped to find work there. Though her mother earned an income as a hairdresser, it was still a struggle to pay the rent and basics were expensive.

But there was little chance that a 17-year-old girl could disobey army officers without consequence. The army stopped the family’s food ration card when Nakfa failed to report for duty. Join the army or starve your family, the message was clear. “The food coupon was for the whole family,” Nakfa said. “We don’t have anybody abroad to send us remittances, we cannot afford to buy food from other shops, it’s too expensive. So we rely on the food coupons. To avoid my family being prevented from accessing the subsidised food I was forced to go.” She was given a uniform and sent to a small town in the north west of Eritrea close to the border with Ethiopia.

It wasn’t long before Nakfa decided to escape again. Furious at being refused leave to see her family, she tried to simply walk out, but was caught and punished. “I considered all the problems I might encounter. I could die on the journey. But my plan was, like my peers who settled in other countries, to send remittances to my mother,” she said. “Upon the completion of my punishment I decided to leave my home country.”

A teenage shepherd boy named Kibrom herded his cattle close to the border where Nakfa was stationed. They struck up a friendship. Kibrom was smart and deft on the mountains and forest trails of the border. He knew the safest places to cross and the shift patterns of soldiers guarding the border. When Nakfa confided her plans, he decided to go with her. To keep her company, he said, and protect her from the dangers of being a young woman crossing borders on foot.

Nakfa and Kibrom walked for hours, unseen by the border patrol.

They were frightened, exhausted, but certain of their path. Thousands had walked it before them. Every month 5, 000 people leave Eritrea. The profile of the people fleeing is getting younger. Like those before them and others since, Nakfa and Kibrom traversed mountains, forests, steep hills and trenches. Then they came to the river.

In some seasons the River Marab is shallow and easy to cross, but the teenagers were unlucky. The water flowed fast and lapped over Nakfa’s chest. “There were two people swept away by the river when we were crossing,” said Nakfa. Kibrom was calm. “For me the fact that I have grown up near, whether it is deep or fast flowing, it is the same for me. I can swim and I can manage to cross,” he said.

Kibrom is 19 and grew up in a rural village close to the border between Eritrea and Ethiopia. He was the middle child in a family of nine. After leaving school aged 11 or 12, he worked as a shepherd herding goats, cows and other cattle. His family sold firewood, charcoal and what crops they could grow. “We could afford life,” he said. “We could help ourselves, but we couldn’t help others.”

Now he had chosen to help Nakfa, he cared for her as a sister. “She shared her plans with me, that she wanted to leave our home country. I decided to help,” he said. “She could face rape or something else bad or be attacked by wild animals or drown in the stream. So I decided to go with her.” Nakfa was tired and struggled to swim, so they waited for low tide. Then early one morning, they crossed the river.

Songs of home: Kibrom playing an Eritrean guitar

When Kibrom and Nakfa first arrived in Ethiopia they were separated for two weeks. Nakfa feared she would never see Kibrom again. He was more sanguine. “Once I crossed the Marab River I convinced myself we could face anything. I wasn’t afraid,” he said.

Any euphoria Nakfa felt on reaching freedom was fleeting. The first thing she did was attend a makeshift funeral for a woman who drowned trying to cross River Marab. Then she was taken to a refugee screening centre where she was surprised to find others like herself. It depressed her. “Women, children, mothers, many brothers. I didn’t expect so many people to have left their home country.”

Kibrom and Nakfa found each other again in the Adi Harush refugee camp, buried in the lush valleys and mountains of the Tigray region of Ethiopia, in a place called Shire, close to the border with Eritrea and a long way from the nearest city. The camp is home to a fluctuating population of round 8,000 Eritrean refugees. The camp opened in 2010, but only in recent years has it began to look habitable: the tents have been replaced with brick huts, built using supplies provided by the Norwegian Refugee Council. Several NGOs and charities offer jobs training, and language and literacy classes. The UNHCR puts on screenings and distributes leaflets alerting refugees to their human rights and warning them of the dangers ‘onward secondary migration’. Onward secondary migration is how humanitarian organisations and the refugees themselves describe the irregular trail from Africa to Europe. The information is designed to subtly deter people from leaving, rather than explicitly tell them not to. Even so, across the four refugee camps, including Adi Harush, in the Shire region, 40 per cent of new arrivals leave within three months, 80 per cent within one year, according to UNHCR data.

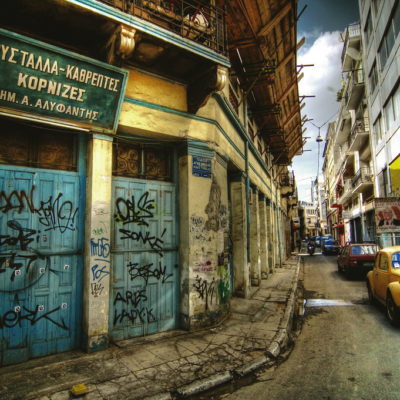

Adi Harush refugee camp in northern Ethiopia

Now having escaped the brutality of military service, Nakfa wondered how she could fulfil her next ambition: to find work to support her family in Eritrea. One of the first things she did on arrival was to create a Facebook account to contact her mother. (Relations between Ethiopia and Eritrea remain fraught; phone calls from Ethiopia to Eritrea are banned.) “Once I told her my whereabouts she cried,” Nakfa said. “I thought she was going to ask me to send money, but she said no, what she really wanted to know was my whereabouts.” Nakfa often boasts that she is the first in her family to escape Eritrea. But obligation flowed from such an achievement: money must be earned and sent home. As weeks turned into months, Nakfa grew desperate.

Ethiopia recognises nearly all the refugees appearing bedraggled at its borders, but the sheer number means support is limited. They are mostly stuck in border camps, where there are few opportunities for work. Eritrean refugees can only leave the camps if they have money or relatives in urban areas. In the Shire region, home to a handful of Eritrean refugee camps, there are pockets of comfort in some of the bustling towns featured on tourist trails from Axum airport. But Ethiopians living in the tiny hamlets surrounding the refugee camp have very little. Their poverty mirrors that of the refugees. Some NGOs even share resources, such as clean water, between the two communities. Nakfa couldn’t see how she would find work here, but she didn’t have any money to leave either.

Nakfa buried her anxiety by immersing herself in camp life. “If I stay home [in her hut], I think too much. Why am I living here? Why am I staying here? But if I leave home, then I entertain myself, I think less.” Babysitting for her friends was one way to stay busy. Hoisting a chattering child to her hip when mum was busy selling food or cleaning. Her favourite chattering child is the daughter of her neighbour Amleset. Nakfa likes babysitting her, “because I have a sister like her and when I am with her I feel good”.

Nakfa: “I have a sister like her and when I am with her I feel good”

The months waiting turned into a year. As she approached 16 months in Aid Harush, Nakfa had completed all the education opportunities open to her: courses in music, drama, dancing, poetry, computing. She wrote her own songs, melancholy tales of Eritrea, and performed in a show staged in a nearby town, part of an effort to reduce local hostility towards the refugees. Nakfa sang of home. “When I was singing about Asmara I was about to cry. I feel emotional, close to tears.”

Music consumed her, it was a way of reckoning with her situation and a way to escape it. She danced traditional Eritrean dances with her friends and began to teach the younger children. “When I’m dancing I don’t even feel like I am a refugee,” she said. When the Jesuit Refugee Service built a suite of classrooms at the bottom of the camp, Nakfa soon began to spend all her time there. She jammed with older musicians, her vocals reminded them of the traditional high pitched tones of classic Eritrean pop singers.

Nakfa and other young refugees learning traditional Eritrean dance

But there were times when Nakfa had to return to her hut.

There she was always restless. It had been more than a year since she left home and what had she achieved? “The biggest problem is that I need to help out my mother.”

Every day people leave for Europe, crossing Ethiopia’s border into Sudan. The same dangerous journey she attempted as a schoolgirl. On Facebook, news is constant: a friend in Holland, another in Germany, Switzerland. One friend dead. “I would consider going along with my peers to Sudan,” she said. “But there are too many risks on the journey. You could drown in the sea, you could get killed, you need to have money.” Even so, at times she thinks taking the irregular route to Europe is the only way to “put myself in a higher position” and “to support myself and send remittances to my family.”

The only certainty of Nakfa’s future in Adi Harush is the endless wait. “There are girls and boys like me who stay six years long here, who haven’t had any success for resettlement. I fear becoming like them,” she said. “I cannot predict my future, but I will go one day. I will see my chance. There are women who managed to reach their destination.”

Having fled twice, it is unlikely Nakfa will stay put. The only questions are how and when she will move, and what will happen to her on the way.

Next week Part 3 – Camp Life

Photos by Gabriel Pecot ©