Inspired by a single sentence she snapped at her mother, Muna Alzuhairi’s story is about cognitive bias, internalised racism, anti-immigrant prejudice and the supposed power of the English language and accents. But, beyond this, it’s a love letter to a fantastic mum who is unfairly overlooked and underestimated.

Muna Alzuhairi is the joint-winner of the University of Warwick’s eighth annual Writing Wrongs Schools’ Competition, organised by the Centre for Human Rights in Practice. This is her winning article which she reworked with Lacuna Magazine during a paid summer internship.

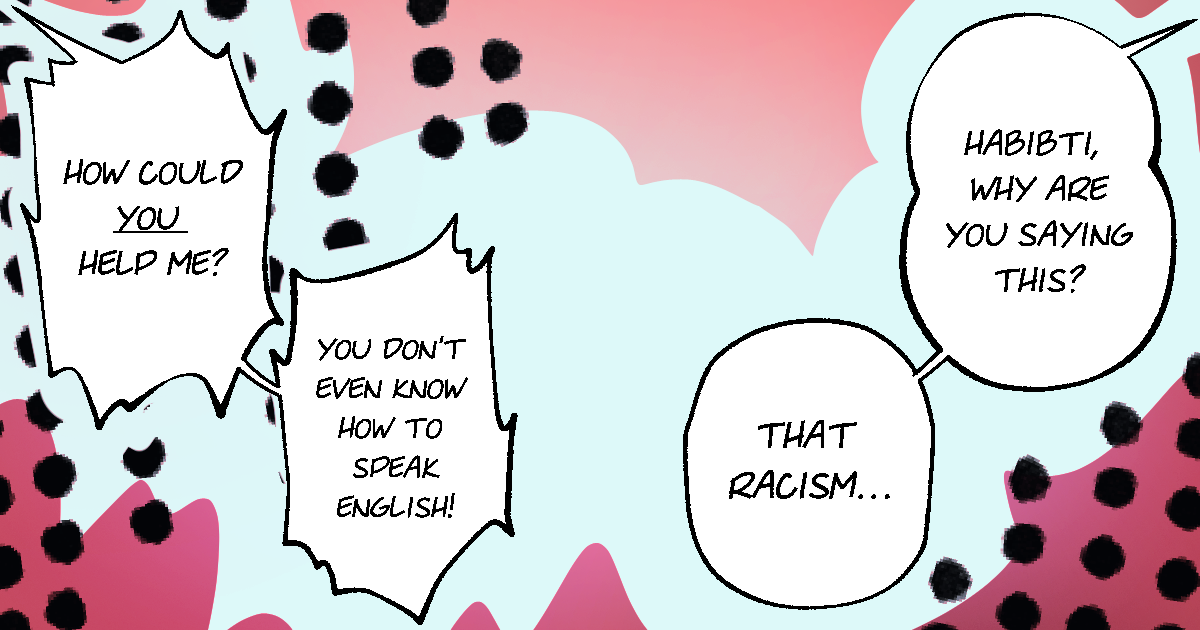

“How could you help me? You don’t even know how to speak English!” I snap, the anger seeping through my mind and into my words.

I wait, expecting a response from my quick-witted mother, but I don’t get one. I look at her. My eyes, a reflection of her own, scanning her face. I watch her buffer, attempting to translate my words into the appropriate language. I watch her try to twist the Arabic she knows into English she can use. I watch her buffer, attempting to produce a response that won’t cause me to turn my nose up at her. I watch as she tries: “Why you are saying this? This not nice. Am trying to help.”

She waits, expecting a response from her equally quick-witted daughter, but she doesn’t get one. Her eyes, the template for mine, scan my visage. The scowl I wear, not a result of my stress, but of the disgust at the disorder of her words, the fact that she cannot grasp simple grammar I understood before I could ride a bike, and at the accent that humiliated me throughout my childhood, renders her silent.

My face softens as I realize that her English response was a defence against my English insult.

“Sorry habibti,” she half-whispers. I pause. My mother is not one to apologise quickly.

“I am dentist,” she continues, “That racism. Discrimination. You… You hurt me.”

My lips part to produce an automated defence but my mind makes no attempt to create any noise to support me.

“I can speak English but maybe I got some accents,” she continues. “My patients, they speaks to me, they even likes me!” she finishes with a hushed tone of pride laced between the words she spoke back to me.

I think back to my sister and me giggling at mum’s mispronunciation at the dinner table. “Who has been the most racist to you?” I ask jokingly, expecting her to say the woman who drunkenly ordered her to go back to her own country in the street, or any of the others who had become another statistic stored in the back of her head.

My sister and I continue to laugh. She ignores us. Without hesitation, she responds: “You.”

Me? Me?! Me. I was a statistic. In fact, I was the primary statistic. The racism I had internalised and faced myself, I had been projecting onto my mother.

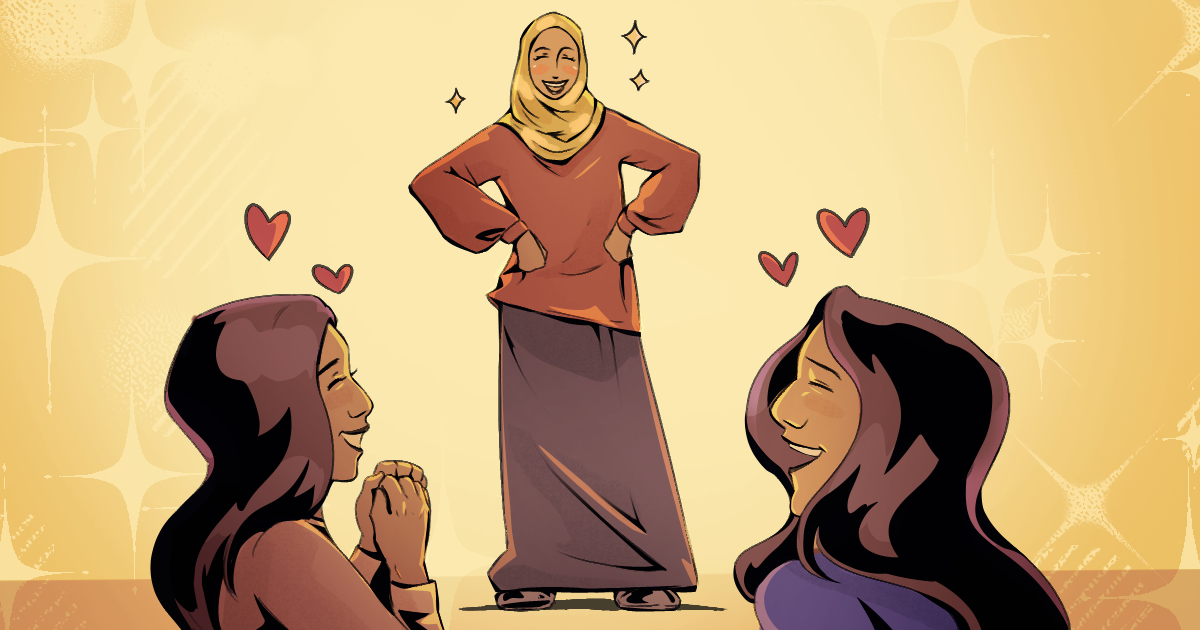

I return to the current moment and begin to smile at my defeat. My grin widening as I realise the power my mother holds, the power to call out those who undermine her, and recognise her own value. She knows her importance as the owner of the hands that carry my heritage and my future, the back that held my weight when I tore my ligaments playing football, and the arms that I will lean on for as long as I need to.

I look again to my mother. I let the admiration wash over my face, and I soak in it. I think of all that she has done, and all that she will do. She was – and still is – a powerful woman in a powerful place. I reply with a simple: “Love you mum,” hoping my three words will erase the anger of the previous moment, and replace it with pride.

But still, it plays in my head. The incessant guilt continues to hang over me, and I try to imagine myself in my mum’s position. I think of the simple tasks that my mother would have once deemed anxiety–inducing feats: ordering a coffee for example. I imagine her, shortly after leaving war in Iraq for a safe English haven in 2011, trying to read the menu and decipher the pronunciation and meaning of words such as “cappuccino” or “frappé”. Back home we would have just said “gahwa” and been understood, but things were different here.

I think of the hopeless feeling she must have had when trying to get around Waterloo station for the first time, how she must have felt as though she was trapped in a maze which everyone but her knew the way out of.

I often feel angry that people undermine my mother until they see her in scrubs, as though she had to have an “established” job to be worthy of respect. I often feel angry that they view her as unintelligent, or that they over-explain jokes and idioms to her, thinking that she isn’t capable of understanding them.

There are moments when I have been so angry with the way my mum has been treated, but there have been moments where I’ve been the perpetrator too.

It occurs to me then that from the sound of my voice alone, nobody would guess that I wasn’t from the UK, but my mother didn’t have that same privilege, and for that reason there was a strange imbalance of power between us.

She was older and more experienced, but I could tell you the difference between a cappuccino and a frappé, and I could find my way around Waterloo just fine. She had two degrees and brought new life on earth, but I could pronounce “pronunciation”, and I could explain what an Oxford comma was.

Read more: How can teachers begin to decolonise the curriculum? There may be more opportunities than you think…

I exhale as I realise my mother isn’t the woman she once was. She can do all that I can, and those anxiety–inducing feats are now routine for her. She has taken the rocks life as an immigrant have thrown at her, and used them to build a castle of compassion and creativity, of strength and success.

The next day I sit my exam. And it turns out I was right, she couldn’t help me. But she had helped in many other ways; in ways that were significant beyond English language paper 1. She helped me in ways that made me a good experience to others, ways that shaped the frameworks of my identity but allowed me to be the one to build who I am.

When I stopped to think about my mother’s place in society and the evolution of who she was, I came to realise that the bulk of my opinions were ideas that I had internalised from the society around me that turns its nose up at those who arrive in a new country looking to build a new life, without the equipment to do so.

As immigrants move through their situations, searching for the means to acquire this new life, they change. Their accent may waver and their personal beliefs may be altered too. They may begin to dress differently or falter in their traditions. However, I believe that their internal system never changes.

I see my mother’s attitude and mode of communication remains very Middle Eastern. Simply the sounds of her kissing her teeth, or muttering words like “yallah” when she wants me to hurry up, or “inshallah” to say “hopefully” but really mean “no”, were concepts that could not be translated into English. Their authenticity could not be transferred except through the veins of those who brought them to this country, and passed them down to people like me: the children of immigrants. It is these things that make my mother the woman she is, and me the person I am.

The continuing idea that English is superior as a language may be rooted deep in global history. The British Empire subjugated substantial parts of Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, a power play with a long and complex legacy. Now, English is known as “the global language” with many of the world’s most powerful institutions, like the United Nations, using it to communicate.

So, my mother’s accent, her over or under pronunciation of words, her slight misuse of common phrases – things that I was so ashamed of, things that I loathed, were all signs of her intelligence. I remember feeling humiliated at the white children who laughed at the way my mother arranged her sentences: “ You had good day habibti? Was nice?” she asks seven-year–old me as my classmates snicker in the background. The innocence in her question renders her oblivious to the fact that they are mocking her. The anger in me forces my full attention to the cruelty of their actions, leaving her without a response.

Read more: We polled EU citizens on what they want asylum policy to look like – their answers may surprise you

“When you gonna do 11 plus, you gonna go to good school!” she tells 10–year–old me, as my classmates snicker again behind us. The innocence in her statement renders her oblivious to the fact that they believed that a woman like that could never raise someone clever enough to be worthy of a grammar school education.

The anger in me urges me to tell them that she spoke that way because she can speak two languages and not one, that she was just as intelligent as their parents – but I simply wasn’t brave enough. I wondered who decided English was superior to other languages, and who made accents and stupidity synonyms. I concluded they were likely the same person, and for my own peace of mind, I told myself they were only jealous because English was probably the only language they could speak!

Now that I’m older, I can tell you that if I asked you to look to those you value or admire, but specifically to those who didn’t begin their lives here, you might see that many of them look and sound slightly different. Their sound carries power and a history that is unable to be expressed in words, so is laced between them instead; their accents symbolic of the transition from struggle to success. Their over or under pronunciation of letters holding a hidden plethora of experiences that brought them the ability to transport those words from one language to the next; and their slight misuse of common phrases a display of their constant endeavours to go further in learning.

In essence, the first-generation immigrant never stops thriving, and their power never dies. An accent is not a defect. I wasn’t brave enough to say it then, but I am now.

Maybe my mum can’t pronounce “pronunciation”, or explain what an Oxford comma is, but she’s got two degrees and without her you wouldn’t have your teeth. She matters to me and she should matter to you too.

All artwork by Isabelle Broad.

Read more: