The third instalment in the Refugee Tales series, published this month by Manchester independent publisher Comma Press, features a new collection of personal accounts that humanise the “refugee crisis”.

This modern take on the Canterbury Tales features the stories of refugees, as told to writers including Monica Ali, Lisa Appignanesi, Bernadine Evaristo, Abdulrazak Gurnah, Jonathan Skinner, Gillian Slovo and Lytton Smith. The anthology supports the Gatwick Detainees Welfare Group, a charity working with people held in indefinite immigration detention near Gatwick Airport.

In this tender tale, as told to Patrick Gale, a man explains why he fled Iran, recounts the difficult journey he took and tells of the challenges he now faces to rebuild his life.

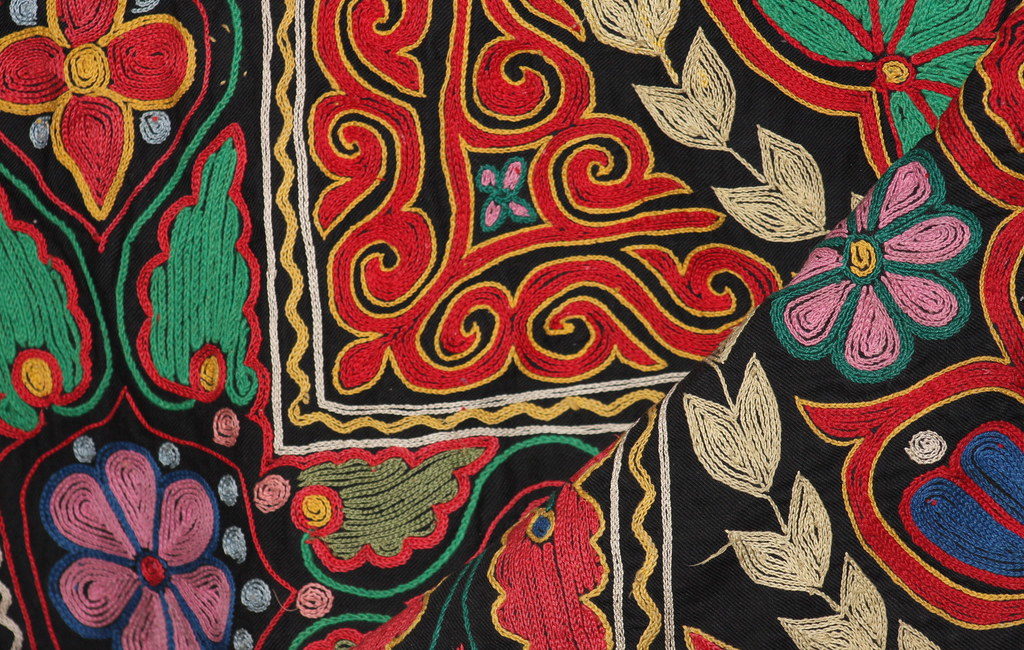

The Embroiderer’s Tale

And yes. So I know this is not correct English grammar. I know not to begin every sentence with, ‘And yes,’ but they are such good words. And: promising there will be more. Yes: a smile in word form, quite different from its equivalent in Farsi, lifting the corners of the mouth, a handshake, a nod, an arm swept open in hospitality. And yes.

So please humour me. After Italy, which I might tell you about later, I find I reach for the good words, even when they don’t make perfect sense. England is another good word, I am coming to see, like ‘cake’ and ‘walk’.

Since I left home, I have learned several things besides English. I have learned that hospitality offered by strangers is a thing beyond the majesty of palaces. I have learned that dogs can be friends. And I have come to see that to have spotless hands is a luxury above feasting.

And yes, I am Iranian, from Tehran. My father and grandfather and great grandfather were tailors. Iranian men, as I’m sure you’ve noticed, if you pay close attention to the news, dress extremely conservatively, but they have a weakness for a well-chosen cloth and a crisply turned hem.

I was trained as a tailor too. We had so much work that my father ran one workshop and I ran a second, from not long after I left school. I was young to be in charge of people, but I was confident and had their respect because I was a good tailor. I am a good tailor. Hand me a bolt of winter-weight wool or a flash of summer-weight silk and my fingers can immediately tell how best to cut it, how best to make it hang from the shoulders, what thread to use with it, what buttons. To my eyes, most Englishmen dress like overgrown children, all colour but no shape.

I was a good boy. Dutiful. I went to mosque to say my prayers, honoured the Prophet, praised his Holy Name, and I pleased my father and mother. My mother was pious and I did nothing to upset her. I read no books other than school books, avoided the Internet, listened only to the singers she approved and never went to the cinema. My one indulgence, which she encouraged me in (because, I think, she secretly liked the sight of fit men’s legs, even when only glimpsed from behind her chador) was football. I had clever feet – as accurate with a ball as my fingers were with a needle – and played often.

And yes, then I met Maryam. I’d be lying if I didn’t admit that there have been many times since when I wished I had never met her. I would still be in Tehran with my family, probably married and a father by now because my mother and aunts were already starting to plan and plot which girl would best suit me.

But thanks to what Maryam started, I have come to see that there is a reason for things. Timothy, the man I live with now, has a framed postcard above his downstairs loo, which says, ‘You came not to this place by accident.’

She was an Armenian. I could tell that from her surname even before she arrived for work. But I am not prejudiced like my mother; I am a craftsman and respect skill.

I set her the usual test, to unpick a seam and resew it along a line marked with chalk. She did this swiftly and neatly; I could hardly see the stitches.

‘What else can you offer us?’ I asked.

She looked at me solemnly and said, ‘I can do invisible mending.’

‘Show me,’ I said.

So she said, ‘Tear something, please.’

I tore a hole in the fabric she had just sewn, a jagged hole, like you’d get on barbed wire, and she took out a needle and reel of translucent thread from her own very neat little sewing kit, and in ten minutes it was hard to tell the hole had been there. And yes, I hired her.

She was a good worker and it was interesting because the other women who worked for me, all Muslim, all veiled, were far noisier than her, always chatting and gossiping and complaining as they worked, as though their veils were thick walls behind which they could say whatever they liked. But Maryam, sitting beside them, was… What’s the word? There’s a lovely English word, like the softest virgin wool. Demure. She was demure: eyes downcast, quiet, sometimes smiling to herself at the other women’s stories as she stitched.

When her first pay day came, I praised her work and asked her if she was enjoying the job and she ducked her head and said, ‘Yes. Thank you, yes.’ But she looked at me briefly, with those eyes that were green like new greengages, not the cowbrown of everyone in my family. And yes, when her next pay day came, she lingered behind the others to be last in the queue. As she took her pay packet, she said her uncle, who she lived with because she was an orphan, would like me to come for supper, to thank me for employing her.

So I went.

I told my mother I was playing football and my football friends that I had a family party, and I went. Her uncle lived in an old house with a courtyard filled with lemon trees around a blue-tiled fountain. It was a special day for them, to celebrate Easter.

And yes, as we ate and they explained and Maryam told me stories, I fell in love with her. As easily as pulling on a glove. She was relaxed, not like at work, because she was with her family. She smiled a lot and her smile was peach-sweet and ticklish so that I had to make an effort to look at anyone else in the room.

As the meal reached the sweetmeat course I realised more people had arrived. The uncle ran a secret church, what Iranians call a house church, and these weren’t born Christians, like Maryam, but secret ones, from Muslim families. They were what my mother called apostates.

‘Will you join us?’ Maryam asked. ‘At midnight it will be Easter.’ She smiled and said, ‘There’ll be special cakes,’ and yes, I saw how much she trusted me because one word from me and these men and women would have been arrested.

So I stayed for the service in the church, which was in a sort of cellar in the oldest part of the house, where candles lit the vaulted ceiling and it was beautiful, perhaps especially because it was hidden, like a beautiful woman under her chador.

As Maryam saw me to the door afterwards, she kissed me swiftly on the cheek and said, ‘Happy Easter and God bless you.’ The kiss, the hint of her perfume and the strangeness of hearing myself say, ‘Happy Easter,’ back left me feeling so dizzy that I drove home without remembering what to say in answer to my mother’s questions and my vague replies probably made her suspicious.

And yes. I went back. Of course I did. My other life, attending to my business, going to Friday prayers with my father, playing football with my friends, became like a fabric left too long in the sun.

Maryam admitted she loved me but said I would have to become a Christian for us to marry. It hadn’t even occurred to me that I could do either of these. So I was baptised in her uncle’s secret church. She kissed me on the lips that time, and gave me a bible of my own. And although we could only be ourselves at her uncle’s house, our murmured exchanges over her sewing at work were now charged like a woman’s eyes when the rest of her face is covered.

I began to dream of how we could move to Lebanon, perhaps, to be together, or to Egypt. Crazy dreams, I see now, but I was in love and lovers are slightly mad.

And yes, it all went wrong, as rapidly as a bolt of silk sliding off a table when you forget to weight it down.

I was playing football with my cousins and some friends. It was a warm evening and I was doing well. I’d scored three goals. The pitch floodlights made the city around us disappear, made the pitch feel like a stage where nothing could be hidden. None of my friends knew about Maryam and me; it was too dangerous. I kept it next to my heart, like the little silver crucifix she gave me.

Suddenly the little boy from next door was there, beside the pitch on his bike. He lived on that bike, running errands, spreading gossip. ‘

‘Hey, Mahdi!’ he shouted out, for everyone to hear. He was grinning. For a moment I grinned back. ‘Your mother has gone crazy and called the police. She found a bible under your pillow.’

Everyone stopped playing. One of my cousins cursed the the boy but my best friend, Parvaz, knew at once it was serious. ‘You can’t stay here,’ he said quietly. ‘They’ll know you’re here.’

So I ran and I drove to Maryam’s uncle’s house. I don’t know how but they had already heard. Maryam wasn’t there. There was no time to wait. Her uncle gave me a fleece and some long trousers in case I got cold later and bundled me into a car for the border. I had my ID card but no passport and no money. I was well off. If I’d been able to go to a bank, I’d have had money, but I was in sports clothes and I had nothing. Her uncle said he was paying and not to worry.

‘God will provide,’ he said.

He had paid an agent, he said, then he pressed a bag of food and drink into my arms and an envelope with Euros in it. I had never travelled. I didn’t know if it was a little money or a great deal.

The driver wouldn’t talk. He said it was safer that way, so we learned nothing about each other. He just drove and played music. Drove and drove. At some point late at night, he turned off the main road then on to a track and drove on with his lights off, using the moonlight, which scared me, but he said it was safest as we were near the border.

Suddenly he stopped in the dark to check his phone. He read a text and flashed his headlights just once. Nearby some more lights flashed. We got out. In the moonlight I saw it was a lorry under the trees.

‘Welcome to Turkey,’ the man said. He told me to piss against a tree because it was a long journey then he helped me climb into the back by shining his torch. It was all crates of fruit. Oranges and tomatoes, I think. The scent was strong. And, in the middle, a little mattress.

I sat on the mattress and he pushed the crates so I was hidden. Then we drove.

I didn’t think I would sleep because of the noise and the smell, and the worry of falling fruit boxes, but I did and I lost all sense of time in the darkness. I wondered if this was all a big mistake but then I realised there was no point even having the thought, as I had no more power to stop the lorry than the oranges and tomatoes did.

At one point, I woke when the back of the van was opened up and I heard the driver talking to another man in a language I didn’t understand, Turkish maybe. And then I woke because we had driven on to a boat. The lorry was rocking this way and that and I was sick under the mattress. I felt bad about that.

Soon after, we drove off the boat and the driver let me out. He said we were in Italy now so I was safe. ‘But don’t give your fingerprints or you have to stay here always,’ he said, ‘And we were paid to get you to England.’

Then he drove one way while I had to walk another and join a queue of people on foot.

And yes, I showed my card and remembered to smile and look the men in the eye because Italy is a Christian country and I’d be safe there. But something was wrong. They shouted at me and they pulled me out of the queue and put me in a truck with some men from Africa, everyone frightened, everyone talking in languages I didn’t know. They drove us to a police station and shut us in cells.

My cell was cupboard small. It was hot with no fresh air and no mattress, just a hard bench. If I needed the loo, I had to call out and beg. They took me to a place with no door and no sink and not always paper. I have never felt so dirty. When they brought me food, it was bread and cheese, so I had to eat with my filthy hands and I worried I’d get sick.

I was there for days. Nobody spoke Farsi, only Italian. Sometimes they tried English but I only knew a few words.

‘Firma qui!’ they kept saying. ‘Sign!’ but what they wanted was my fingerprints and I wouldn’t.

Eventually I cracked, anything to get out, even though I was scared about having to stay somewhere so bad. So I let them take my fingerprints and suddenly they were all smiles and shrugs and they put me out on the street. I washed my hands and face in a very cold fountain and even drank from it then went into a church to pray. After that, I sat on a bench outside the police station to wait.

Eventually a driver stopped. He knew my name. He had been coming by every day at the same time. He had no Farsi but he had a sheet of paper with phrases copied out from the Internet in different languages I could point to. So once he knew my language, he pointed to You can call me Piero and I have been paid to take you to France and No more borders until England!

He was driving a minibus. We drove to a multistorey car park and picked up more people. Women and men and some children as well. At first, nobody spoke except the ones who were travelling together. Everyone was tense, especially when the driver saw a policeman and flapped his hand and shouted, ‘Giu! Giu!’ till we all dropped on the floor out of sight. It was like that all the way to France.

Sometimes we’d relax and people would sing or try sign language and it would start to feel like the strangest holiday, then we’d see policemen with guns and everyone would fall silent and hide behind the minibus’s ragged orange curtains.

When we stopped to let the driver rest or to get food or relieve ourselves, you could tell we were all scared of being left behind. Nobody spoke Farsi so I felt very alone in the group. I worried they’d forget me and I’d be stranded on the motorway. By the time we were in France, most people had left to get into other vans. We drove into a big forest as the sun was sinking.

Piero said something serious, then handed me to some other men. They checked my identity card and asked lots of questions I couldn’t understand. They weren’t friendly; they were frightened. There was nothing to eat.

And yes, they made me sleep in a tiny tent with several other men. One wouldn’t stop crying, even when the others shouted at him. I think someone had died.

We woke hearing a lorry arrive. They made us get into packing cases, wooden ones. They pointed at the air holes, making panting noises to explain, and then handed us each a plastic bottle of water and an empty one. Rude gestures showed what the empty ones were for. They sealed us in and loaded us into the lorry among cases which had other things in them. Not people. I am not scared of the dark. Not very. But I am tall and used to moving all the time. If you get cramp when you can’t stretch your leg out straight, it hurts.

I lost track of time because of the darkness. And my phone battery was dead so I had no light. Once again we went on a boat. This time I wasn’t sick, maybe I was empty. We arrived somewhere and the lorry started up again. I was sure we would be checked. I was sure I would soon hear shouts and splintering wood but no, we just drove for maybe two hours. We stopped at last and I could hear packing cases being ripped open at last. People talking in their languages. ‘Hemel Hempstead,’ a man was saying, quite angrily.

‘Hemel Hempstead. England. Go. Go now!’

That’s what he said to me when it was my turn to be let out. ‘Go. Hurry!’ But my legs were so cramped I could barely move so he had to help me down to the ground before he drove quickly away. We were in a car park in a town. It was night. Street lights in the distance and a big road.

I found myself on a normal street with takeaways and shops. It was busy with traffic and people, so I could disappear like a thread in thick felt. I tried not to stare at everything. I was worried I must smell bad and look wild.

I heard a man and woman speaking Farsi. And yes, it was so surprising I smiled – although they were arguing – and he saw and broke off to say, ‘Hello, my friend.’

‘Hello,’ I said.

The woman looked suspicious and told him, ‘We’ll be late,’ but he looked kindly at me and said,

‘You’ve just arrived, haven’t you?’

‘Yes,’ I said.

‘Do you have friends here?’ he asked. ‘Family?’

‘No,’ I told him. So he wrote down his number, although the woman was clucking at him like an angry hen.

‘Ring me,’ he said. ‘Arsham. You have one friend here now.’

I tucked his card with my money in my sock and tried to buy some food, but they wouldn’t take my money as it was Euros and then there was a policewoman beside me, holding my elbow.

Every traveller here, every refugee, has their own story as different as they are. The trouble is that all the stories become the same in the same way because they all, sooner or later, narrow down to a lorry, a box, a cell.

They said it wasn’t prison. When they finally found me someone who could speak Farsi, she explained it was a detention centre for people like me with nobody to vouch for us.

I explained to her. I left nothing out apart from the fingerprints in Italy because I was scared of being sent all the way back there, and about Arsham, because I kept thinking of his wife and how impatient she looked as he gave me his number. He looked kind but she was dressed like my mother. I knew she would think me an apostate.

But they kept asking. ‘Who can you ring? Who do you know?’

The detention centre, near a big airport, was nicer, I think, than a prison. There were plenty of meals and the beds weren’t uncomfortable. But it felt like prison because we couldn’t leave and because the women and men were kept in different parts, like in a mosque. There were good things there: I could play football every day in the yard like a cage, which helps when you all speak different languages, and I could go to a chapel and be as Christian as I liked. I started to learn English properly. Every day.

But there were bad things, too: the boredom, the feeling idle and the violence. And football or suppertime could turn into a fight.

I had dreams that woke me up sweating and shouting so that people shouted back or thumped on the door. I found it hard not to cry, especially in the chapel. I went, not just for God but because it was quiet and empty. When I started to cry, I found it hard to stop.

So finally I said, ‘Yes. OK. Yes. I have a friend called Arsham I can ring.’ So they gave me a phone and said ring him and I took the paper with his number and I prayed in my head and when he answered I laughed and laughed because I was so happy it wasn’t his angry wife. And yes, he knew at once who I was and very calmly, like a wise mullah, said let me speak to them.

He was very good. And so was Shideh, his wife, even though she didn’t want me there. Maybe she was especially good because she didn’t want me there.

I slept in their spare room for eight whole weeks. I tried to give them all my money but Arsham only took it to turn it into pounds for me. They fed me, they took me to the library so I could read and have more English lessons from a lady like a grandmother who was not paid but said she did it for love. And they made sure I did not forget the days when I had to go a long way on the train and bus to sign the form for the police and answer questions I was beginning to understand. And, kindest of all, because they were both Muslims, they took me to the door of the local church.

In church I made friends, especially Timothy, who vouched for me when I was taken back to the detention centre when I forgot to sign in one week because I was ill and crying in my room. And yes, Timothy took me in and gave me his spare room and said I could live there free of charge while he helped me to claim asylum.

He has helped in so many ways. He realised I needed to work, although I am not allowed to earn money, so he gave me his dead wife’s sewing machine and I started mending and altering clothes for charity and helping mend vestments at the church.

One day he saw me working on an altar front, a very old one, where the pattern had been eaten by moths and needed a repair. I was puzzling over it because it was not the sort of sewing I knew how to do.

He taught me two new words on the spot and wrote them down for me on the little pad we use: Tapestry and Embroidery. Embroidery can also mean making up stories, or making stories better, which I like very much.

He showed me pictures on the Internet. When I liked a tapestry that looked like a painting but all in silk, he said, ‘Oh, we can go and see that easily.’

And he took me to the palace at Hampton Court and explained its history – most of which I didn’t understand but he told me anyway because his wife was dead and he needed to talk and tell stories. The tapestries there were so big, with figures bigger than life-size and so very beautiful. I made him laugh because he tried to show me the rest of the palace and the gardens, which are beautiful and strange, but I kept asking when we could see the tapestries again.

‘Would you like to learn?’ he asked. ‘Men can learn as well as women.’

So I said, ‘Yes. Yes, please.’ And he signed me up for a course at the Royal School of Needlework.

We learn high up in the attics of the palace. And yes, I am usually the only man there but I don’t mind because the ladies are very kind and tell me I have a gift, like I did for football.

If the detention centre was a kind of hell, the needlework school is like a kind of heaven, and not just because it’s up in the clouds. The rooms are all painted white so the rainbow walls of glass drawers where you can see all the coloured wools and silks waiting are all the brighter.

It is quiet, because we concentrate so hard as we sew tiny flowers and leaves and birds, and it is calm, like the calmest summer’s day with no wind, and oh so clean, because we are encouraged to wash our hands many times a day to keep the fabric unmarked.

I made a red rose for my first exercise, using more reds than I can hold in my mind’s eye and I thought it was full of mistakes, but all the ladies gathered around when I finished and made sounds like doves in a warm courtyard. They want me to stay.

They want me to do exams so that I can teach. And yes, they want me to tell them my story. But I only tell small parts, here and there, because it makes me too sad.

The sadness is bad. Timothy took me to see a doctor about it because some days it was like a heavy cloud pressing down on the bed stopping me getting up. And I was given pills and they help a bit. But they don’t stop the bad dreams and memories. Of the trucks. Of the forest. Of Italy.

So Timothy made me choose a dog in a place like a detention centre for dogs, a terrible place full of sadness and wild barking. Tina is small and very bristly and brown, with eyes the colour of caramel. He says she is a mongrel but I think that sounds ugly so I just call her Tina. He says she is ours, but I know she is really mine because I walk her and feed her and brush her. She seems to have chosen me, he says, because she sleeps outside my room, very close to the door. And if I wake with the sad cloud over me, she knows and pushes and licks my toes and fingers and ears until I get up to walk her. She is better than a pill. And yes, I hold her close, although we were told never to touch dogs at home, and she makes me feel better. She makes me feel now, rather than then.

Timothy says I can ring my mother to tell her I am all right and I nearly have a few times. But then I remember that she called the police when she found my bible. He asks if I want to ring Maryam, if I miss her badly. And yes, I nearly do but Maryam seems so far away now, like a tiny figure in a picture on a wall in a big gilt frame. Sometimes I think Maryam was like an angel, mysteriously taking jobs around Tehran to make Muslim boys fall in love with her and become Christian. I think she will be working somewhere else now shyly saying thank you to a boy who can’t stop looking at her in the hope of catching her eye.

Instead I try to be like Tina, and think only of now. And tomorrow. My next embroidery. Our next walk by the Thames.

I wash my hands whenever I can. Timothy has Pears soap, which is brown and smells of spices and leather. The soap at the needlework school smells of lavender. I sniff my fingers and smell only soap. If I look straight ahead, or down at Tina’s caramel eyes or closely at the blue and purple stitches beneath my fingers, life is good.

And.

Yes.

- Refugee Tales III (edited by David Herd and Anna Pincus) was published in July 2019 by Comma Press. Refugee Tales is an outreach project of Gatwick Detainees Welfare Group, and all proceeds from the books go to GDWG and Kent Refugee Help. The new collection is available to buy from all good retailers or to order direct here.

All images of Kazakh embroidery by Mark Heard.