In the world’s largest refugee camp, Rohingya refugees are using cameras and mobile phones to document their lives for a new magazine.

When the Covid pandemic stopped journalists visiting the camps in the Cox’s Bazar district of Bangladesh, refugees stepped up to tell their own stories.

Now, a group of refugee photographers have combined their images to create an online exhibition and a magazine, Rohingyatographer, to showcase their work.

Rohingyatographer founder Sahat Zia Hero who lives in one of the Rohingya camps in Cox’s Bazar, wants to document life in the camps, both to connect with outsiders and to provide a sense of identity for the younger Rohingya generation.

He says:

“Life in the refugee camp is not easy. More than half our population are children under the age of 18. There is limited access to formal education, so the Rohingya youth have a serious gap in their education, they are at risk of becoming a lost generation.

“Right now we feel like we are stuck because we don’t know when it will be safe to return. The political situation is very complicated. Cox’s Bazar is a beautiful district and it has one of the longest beaches in the world but unfortunately we cannot travel outside the camps. The people in Cox’s Bazar also face many challenges, with poverty, lack of opportunities and climate change.

“But among the Rohingya we have a strong commitment to educate ourselves as well as teaching others. So, photography has grown to be a very popular subject for us.”

More than one million Rohingya refugees are now living in crowded camps scattered across south-eastern Bangladesh. Under military rule in Myanmar, the Rohingya were subject to marginalisation, exclusion and violence for decades. Violence and discrimination escalated in 2012 with riots and mass displacement that saw hundreds of thousands flee to Bangladesh or Southeast Asia before a further crescent of violence in 2015 and again in 2017.

Over the years, refugees in Cox’s Bazar have been helping international journalists to navigate the camps to tell their stories to the wider world. But when Covid stopped that, they took the chance to become storytellers themselves.

Minara is 3 years old. She is looking stylish with her new dress and wearing sunglasses during the Eid Festival. © Ro Yassin Abdumonaf

Sahat says: “As a result of the Covid-19 lockdown and travel restrictions, international journalists could no longer come to the camps. This fostered a collective of Rohingya photographers to start using social media to tell their own stories, so they became journalists and photographers in their own right and now they work remotely for international media outlets.”

Two photographers in the camps use their own DSLR cameras, while others use the cameras on their phones.

Sahat says: “I love photography and I have a few friends who share this passion, because we use photography to advocate for our rights and try to make a difference for the Rohingya refugee community. Photography is our superpower!

“Though we are not formally trained, we take photos every day. Our difficulties inspired us to document our lives by ourselves so that we can share the real situation in the refugee camps, the challenges, our stories, our hopes, our culture, our dreams and happiness to the people around the world through our eyes.

“Each photographer has his or her own individual visual language. Some focus more on a journalistic approach, trying to capture the essence of the story and person they are interviewing, while others are more experimental, playing with curious angles and situations that result in very interesting images. There are no rules.”

The magazine, available in print and ebook, can be previewed here and the interactive exhibition can be found here.

See below some of the photographs featured in Rohingyatographer.

Sahat says: “Photography is a vehicle for self-expression, and as long as we keep practising, we will get results. I myself am still learning every day.

“I use photography to learn about observation, but it also helps me to deal with and embrace the problems we face living here.

“For example, in March 2021, there was a big fire in the camps. Over 50,000 Rohingya lost their homes, and many lives were lost to the fire.

“My shelter burnt to the ground, my family was safe, but I lost everything (again) including my laptop and pen drives where I kept my images and documents. It was a tough time, but I don’t give up easily, so I used my camera phone to document the aftermath of the fire.”

Sahat’s neighbour Zaudha cries while watching her home destroyed by fire. By Sahat Zia Hero

Sahat kept in touch with a Spanish photographer and humanitarian, David Palazón, who he had met in the camp. The two sparked a friendship and David supported Sahat to create his first photobook of images from the camp.

“I enjoyed working with him very much,” says Sahat, “so the idea for Rohingyatographer grew out of that first experience.”

Sahat is one of 11 photographers who have contributed to the magazine and to a virtual exhibition, sponsored by the Embassy of Spain in Bangladesh, The Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation (AECID) and Casa Asia in Barcelona, who organised a webinar in collaboration with MSF and UNHCR Bangladesh. The virtual exhibition has been well received and had UNHCR support to be presented at the Liberation War Museum in Dhaka on World Refugee Day – Monday 20 June.

“One of the big challenges is access to a good internet connection in the camp and WiFi is very limited,” says Sahat. “And although we have received in-kind contributions, we don’t have a permanent sponsor to support financially our project.”

Following the publication of their first edition, the refugees hope to attract sponsorship so that they can publish Rohingyatographer twice a year.

“It’s always difficult for us to make something without any financial support from an organisation,” says Sahat. “It was the Spanish Embassy in Dhaka who helped us with a small budget to design the virtual exhibition. This kind of support helps us to work in the difficult situation of the refugee camp and it encourages us to make something better than people expect from us. But with or without funding, I believe that we can make another important issue.”

The first edition takes the theme of identity with the goal of inspiring pride in younger Rohingya people.

Sahat says: “Sometimes international media does not portray us with the dignity we deserve, so this project is really about allowing our community to present ourselves and to show the world our creativity, talent and aspirations for our future. Although it is very uncertain, we do have a future!

“We use photography and art to express our hopes, dreams, happiness and the challenges that we face every day in our lives in the camp. I hope people will be interested to see the life of the Rohingya refugee community through our own eyes.

“We want to share our experiences with them and hopefully help people to see us in a new light – our life with all its colour. We know we are much more than our surroundings, than the labels we are given.

“We want people to see us as human beings, just like everyone else, and we want to share our hopes and dreams, our sadness and our grief with others, to make connections.

“There are always news stories that should be heard. For example, there was a deadly flood in the monsoon last year that affected more than 12,000 refugees, and the fire here in March 2021 left 50,000 refugees homeless. We refugee photographers were the first responders.

“We documented the situation of the community by ourselves and shared with people around the world. The world could see the hardship of our community through our eyes. So, we are doing that. We are covering the stories of our community which are new and unheard by the rest of the world. We want to make sure our voices are heard and that the Rohingya people will not be forgotten.”

“The way we document our lives by ourselves is different to seeing our lives through the eyes of others who are not refugees. We are neither trying to make beautiful headlines nor commercial stories through our photography. We are trying to share with people around the world the reality of what is happening in our lives, as well as keeping the memory alive for our next generation.

“Photography is our best language because it says more than words and shows our reality.

“We will never give up and will never stop struggling to make change and to give our community a better future.”

The photographers behind the first edition of Rohingyatographer are: Sahat Zia Hero, Ro Yassin Abdumonaf, Azimul Hasson, Abdullah Khin Maung Thein, Hujjat Ullah, Md Jamal, Shahida Win, Enayat Khan, Md Iddris and Omal Kahir. Spanish photographer David Palazón is acting as mentor, graphic designer and curator.

Rohingyatographer magazine, available in print and ebook, can be previewed here and the interactive exhibition can be found here.

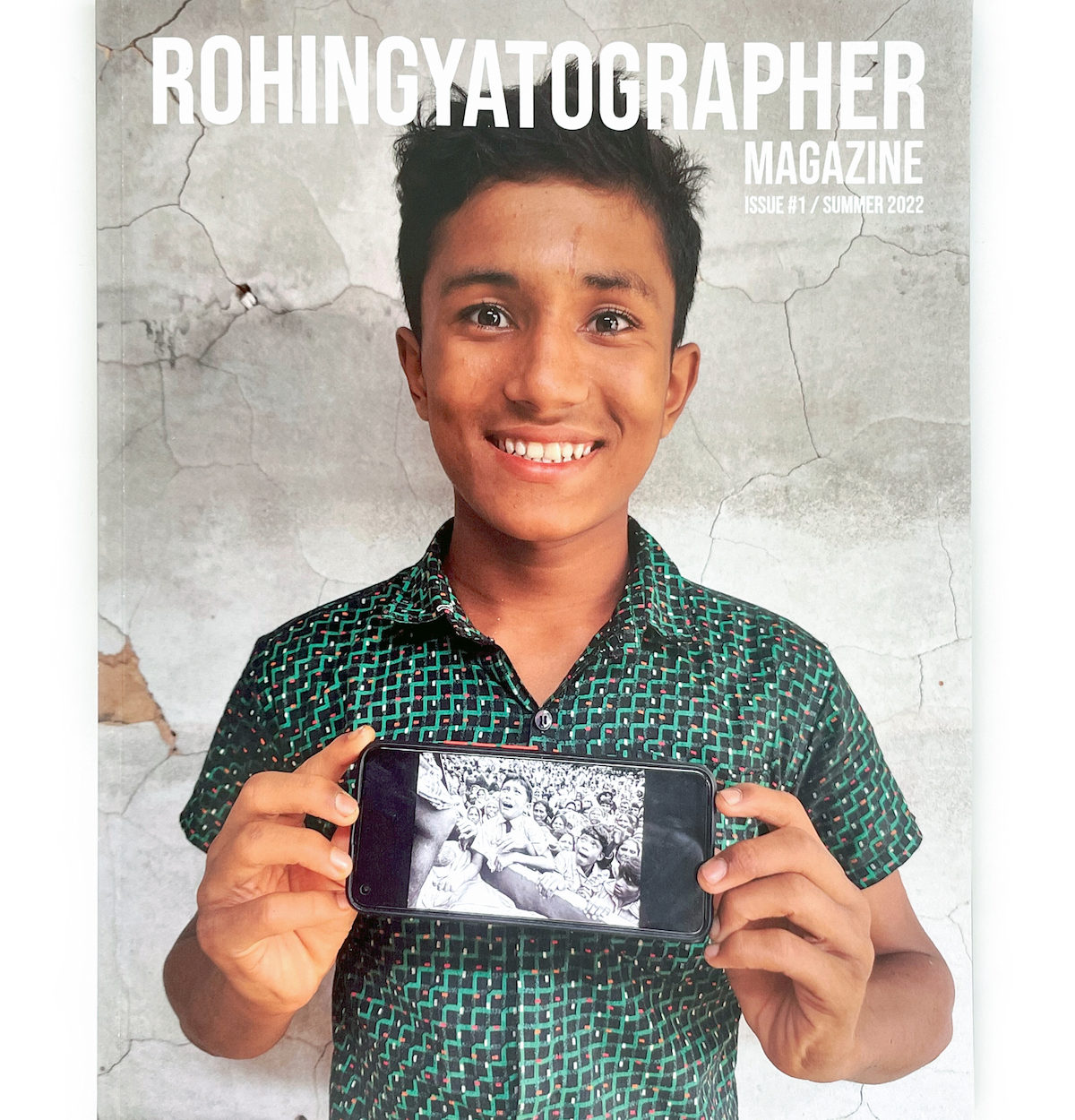

Who is the magazine’s cover star?

Md Hasson “Asun” – by Sahat Zia Hero.

Md Hasson—or “Asun” as his friends like to call him— pictured right, is 13 years old. He was only eight in August 2017 when Canadian photographer, Kevin Frayer, took his portrait crying desperately while climbing onto an aid truck. Kevin was covering the massive exodus of Rohingya fleeing into Bangladesh to escape the genocide perpetrated by the military in Myanmar.

Hasson’s image was named one of the 10 best photographs by Time Magazine in 2017 and shortlisted for a Pulitzer Prize. The photograph became an iconic representation of the suffering of Rohingya people featured in news articles across the globe. Hasson was born deaf and as a child he was unable to speak. He has developed his own remarkable language of gestures to communicate with others. His playful and creative way of expressing himself has made him very popular among his friends. Hasson says:

“I was once a young kid crying for food, but I am now happy and keen to participate in telling the story of my community. People will know that I am not voiceless.”

Hasson’s mother died the day she gave birth, and he was raised by his aunt and uncle. In October 2017, they fled to Bangladesh. Hasson, like most boys his age, spends most of the time in and around learning centres in the camps. He would benefit from an education programme tailored towards children with special needs, but opportunities for those with different abilities are extremely limited in the refugee camp.

Sahat, who took Hasson’s picture for the magazine cover, says: “As a junior member of the Rohingyatographer collective, we provided him with a small camera so he can experiment with the medium of photography and develop his skills and self-expression further. Perhaps one day he might become a famous photographer.”

How to support

- Buy a printed copy of Rohingyatographer magazine, or an ebook version, here.

- Buy Sahat Zia Hero’s photobook, Rohingyatography, here.

- To sponsor the magazine and future projects, email rohingyatographer@gmail.com

Read more: