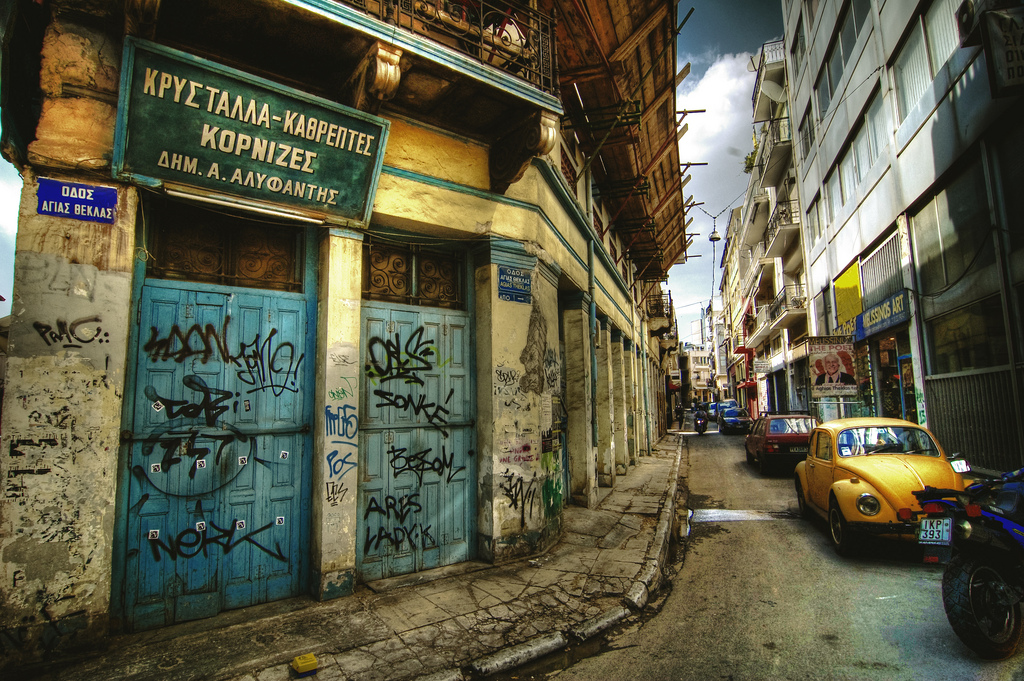

I ignored my nerves and followed the young man. He walked briskly, confidently weaving a path through Athens’ city centre and out to its shabbier outskirt. Dusk fell, and I began to feel afraid: the cramped streets all looked the same and I couldn’t read Greek script on the street signs. I had no idea where I was.

I looked nervously at Ezmerey striding ahead of me. Clad in jeans and leather jacket, a phone glued to his ear, he laughed, switching easily from Arabic to Greek, and occasionally turning to talk with me in near perfect English. We had met a few hours earlier. He was not the first refugee I had interviewed in Athens, but was the first to trust me. He had been a football player in Afghanistan, and had begun to impress in one of Athens’ smaller leagues. But his chances of a glittering football career had been cut short by Greece’s then dysfunctional asylum system. Ezmerey’s application for asylum was one of tens of thousands; it could be years before he received an answer.

Still, the sense that I had been too trusting only disappeared when eventually we turned into a dilapidated building, walked up several flights of stairs, and I found myself sitting opposite two young Afghan women. As children crawled around us and men spoke loudly in another room, I got my notebook out and said: “Tell me your story.”

The fear I felt at being led through a foreign city late at night with a near-stranger for a will-o’-the-wisp story fell away. Here were people who had fled real danger and instability, and were now battling a European bureaucracy indifferent to their plight. They had sunk into poverty while waiting to find out if they would be allowed sanctuary. Meanwhile, they could not legally leave the country or find work to support themselves. My job was to listen and tell their stories.

Two years later, I sat listening to students discussing their work at the University of Warwick’s Writing Wrongs class, and was reminded of the stories I was told that winter in Greece. I attended the seminar as part of Lacuna’s editorial team to give a talk about the process of putting together the magazine.

We discussed everything from how to combat existing mainstream narratives and connect personal stories of injustice to wider, systematic violations of rights, to the ethics of writing about other people’s suffering. At one point, Maureen Freely, the course tutor, in an attempt to elicit a thoughtful answer, asked ‘why do you bother?’

The question made me think of Greece, when, plagued with my own doubts, editors ignoring pitch after pitch, worrying about my own sustenance, I instinctively followed Ezmerey, in search of a story.

And by following Ezmerey I met Farida, one of the Afghan women in the house, who told me a story of floating for 16 hours in the Aegean Sea, clinging to life, and watching fellow passengers drown. Before Europe, Farida tried her luck in Iran, where her children were denied an education and she struggled to find work. But the pattern of poverty and discrimination she experienced in Iran continued in Greece. The dingy flat where we met was shared with 23 others, all piled into two rooms sleeping on rugs. Farida’s 9-year-old son, a pale child with dark circles under his eyes, escaped the flat everyday to sell cigarette lighters. They were trapped in Greece, unable to leave because of EU regulations limiting the movement of asylum seekers. Yet she harboured hope. “We don’t have any more hope for our lives,” she says. “The best hope is for our children.”

Farida’s story reminds me why I bother. She hoped that the telling of it might change something. Her story is symptomatic of a global injustice, which can be traced across continents from the footprints of people who dare to run. Telling her story exposes the behaviour of governments, bears witness to these atrocities and prevents a cynical world from saying we did not know.

Telling stories is important, but change takes time. For things to change, there must be enough people asking why bother, and deciding to act. Choosing the best way to act is not an easy decision to make. For me the most difficult obstacle is the lack of a blueprint. But, over time, what is becoming clear to me is that the people doing useful things to combat injustice rarely follow a plan. Instead, they do what they can, when they can, with the skills they have. And rather than offering others wanting to act on injustice a path to follow, they should simply be an inspiration. A starting point, not a blueprint.

It took a series of storytellers to catalogue the horrors of Greece’s chaotic asylum system, so that refugees and migrants are no longer sent back there from other European countries.

Under the EU’s Dublin II regulations a person must apply for asylum in the first member state he or she enters. If an asylum seeker moves to another European member state to seek refuge there, their fingerprints will appear on a central database with details of their first claim. They are then deported to that country.

Most asylum seekers and paperless migrants enter Europe through Greece, a country whose asylum system was already in crisis before its financial problems hit. By 2010 the backlog of asylum claims had crept towards 70,000, the immigration holding centres were severely overcrowded and poorly kept, and hundreds of refugees lived in various states of destitution in cities like Athens. Yet other European countries still deported refugees back to Greece.

After years of NGO and journalist reports, protests by angry citizens, and people like Farida choosing to speak out, European countries have stopped deporting people to Greece. Pivotal was the 2011 European Court of Human Rights judgement in M.S.S. v Belgium and Greece, which decreed that Belgium had acted unlawfully in deporting an Afghan asylum seeker to Greece. The court also held that both countries had violated the asylum seeker’s human rights because of the deficiency in Greece’s asylum system and the deplorable detention conditions there.

One of Lacuna’s aims is to challenge the indifference to the suffering of others and stimulate action. To that end, over the next few weeks, we’ll publish a series of frank, short interviews with people working across a range of professions, all working for the same goal, to challenge injustice and promote human rights. This will act as a useful starting point for those of you who read Lacuna and decide to act. And if you find yourself plagued with doubt or fear, asking why bother, look on these as a source of reassurance. There is no right way to tell a story, the important thing is that it is told.

The first of our interviews is with the author and journalist Clare Sambrook

Photo by Zé Valdi