Rebecca Omonira-Oyekanmi reports on the plight of women with uncertain migration status fleeing domestic violence.

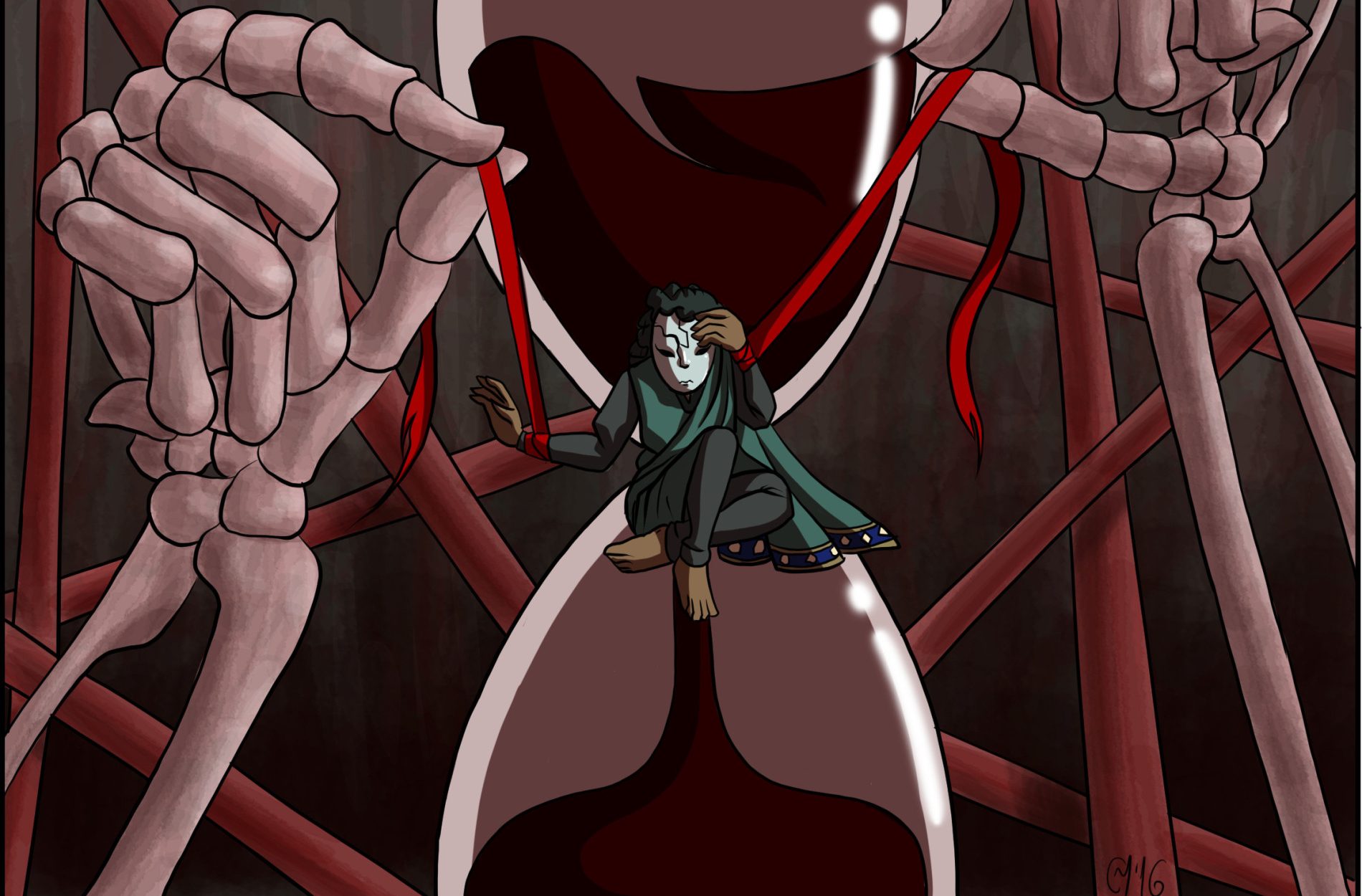

Image by Chris Manson

He stopped hitting her and left the house. Nabeelah* tried to move. She and her husband lived with his parents and a handful of relatives, but it was unlikely anyone would help if she called out. There was a hierarchy in the house and she was at the bottom.

The family used her husband’s violence to intimidate and threaten her. Nabeelah was young, just 18 when the marriage was arranged. Before that she’d wanted to study medicine, but her parents believed the young man born and bred in England was a better proposition. She left the country of her birth and her family to live with him in the UK, where thanks to her quick mind she easily picked up English because his Urdu was so poor.

Her back was sore and she worried he would soon come back. I don’t want to die, she thought. For two years she’d been treated “like an animal”, sworn at and beaten up. He had isolated her from her family back home, told them lies about her. But it was the first time she thought he might kill her. She found her phone and sent a text to her only friend. A second later the phone rang:

“What happened?”

“He called his friends and he said he is going to stab me. He beat me up really badly. I can’t move my back. It’s swollen. I don’t know what to do. Just call the police. Please. I need help. I am in danger.”

Erin Prizzey created the first refuge for women fleeing domestic violence more than forty years ago in 1971. Referring to public authorities, the police and social services, she said in an interview at the time: “Nobody seemed to be doing anything constructive to help. They just seemed to be sending these women back to the men who beat them, and some back to be killed.”

Within a few months the refuge, a four-bedroom terrace house in west London, became a place of safety for hundreds of women, and in the following decades similar refuges would open across the country. In the decades since, feminist activism and women’s organising has helped shift public attitudes towards violence against women. Slowly, political change and legal redress has followed. Marital rape was categorised a crime in 1991 and the Serious Crime Act 2015 decreed that coercive or controlling behaviour in a domestic setting is an offence. Earlier this year the government published a strategy to deal with violence against women and girls (VAWG), and institutions like the police are regularly assessed on how they respond to domestic violence.

But there are gaps in the law and in institutional responses to domestic violence where it affects some refugee and migrant women. To borrow Prizzey’s phrase, for a range of reasons, there is a “terrible, relentless uncaring” by authorities towards victims of domestic violence who also have insecure migration status. These women are caught in an intersection of ever-changing, stricter immigration rules, dwindling local authority budgets and immense financial pressures placed on women’s refuges. According to the latest Women’s Aid Annual Survey published in May, 662 women were turned away from domestic violence refuges in 2015 because they had no recourse to public funds, a condition imposed by the Home Office on people granted temporary leave to remain in the UK. This figure is a jump from the 389 no recourse refusals counted in 2014.

There are gaps in institutional responses to domestic violence where it affects refugee and migrant women

Most refuges rely on housing benefit from tenants to cover rent; when a woman with no recourse to housing benefit turns up, it is a cost many refuges simply cannot afford. The Women’s Aid Annual Survey 2015 revealed that a lack of capacity to support women with no recourse to public funds was a key concern for many refuges already fighting funding cuts. Across England, refuges are being asked to ditch specialist services, such as BAME or women-only refuges, and provide a generalist service. Last year Imkaan, a black feminist VAWG organisation, reported that 64% of their members running refuge services have been asked to reduce bed space and provide a more general service. Apna Haq, the only service for the ethnic minority women in Rotherham, lost its contract last year after the council decided to go for a generalist cheaper provider. With refuges struggling to secure funding for services that address cultural differences among British citizens, it is unsurprising that the sector is unable to provide services for women with acute asylum and immigration needs.

On 11th May this year the issue was raised in a parliamentary debate on the domestic violence refuge crisis. The secretary of state for communities and local government Marcus Jones said:

We want to end violence against women in all its forms … Our goal is simple: that no woman is turned away from the support she needs. All our efforts are focused on achieving that. As many hon. Members have said, refuges are a lifeline that provides a route from fear and violence to safety and independence … we must also ensure that the support women need at crisis point is available.

He was interrupted by Anne McLaughlin, a Scottish MP who has previously raised the issue of women with insecure migration status fleeing domestic violence. She said: “When the Minister says that no woman will be turned away, does he mean no woman? Does that mean that all women should be entitled to these services? If he agrees that they should, will he do as I asked earlier and make representations to the Home Office and the Home Secretary that they look at changing the anomaly of women who are excluded because of their insecure immigration status? I do not think the Home Secretary intended that.”

Over the past year and a half, I have researched this anomaly and interviewed women affected, as well their lawyers and sector workers. What follows is some of those stories. My findings were published as part of a bigger report published by the Ferret, a Scottish investigative journalism platform, which reported on the situation for women in Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Forty years after the first refuges opened, women are again being told to stay with their violent partners. Whereas refuges might have once stepped in, a regime of austerity prevents them. And where the law ought to enforce their right to live free from violence, in this instance, their migration status trumps that right.

Nabeelah and her husband were married in Pakistan and after a couple of years she moved to the UK with him. He got her an 18-month student visa, rather than a spousal visa. Her migration status was temporary and she had no recourse to public funds.

On International Women’s Day this year the Home Office published its strategy to end violence against women and girls (VAWG) in the UK and abroad. It spoke of the need to make domestic violence “everyone’s business”, dealt with by government, civil institutions and society at large. But the strategy offers no solution for women like Nabeelah, foreign national women living in Britain who are forced to choose between destitution and violent relationships because of their migration status.

Under immigration law a person given leave to remain in the UK may be subject to the condition that they are without recourse to public funds. These public funds are set out in the Immigration Rules and include a range of working age benefits including Jobseeker’s Allowance, Housing Benefit, Child Benefit and Disability Living Allowance. People with permission to stay in the UK as a partner or spouse of a British citizen might have no recourse to public funds. If their relationship breaks down and they can prove it is because of domestic violence, they can apply for temporary indefinite leave to remain and to have the no recourse status lifted under the destitute domestic violence concession.

This concession is a result of several decades of campaigning by the Southall Black Sisters and other VAWG groups, who describe the original immigration rules as both racist and sexist. Their work was supported by Amnesty International in 2006, who joined the campaign and argued that denying women access to safe shelter and subsistence so they could flee abuse contravened a number of international treaties and domestic human rights law.

The latest incarnation of the domestic violence concession has been in place since 2012 and is limited to a handful of women with no recourse status. To qualify you must have entered the country on a spousal visa and be married to a British or settled person (this excludes refugees, an exclusion currently being challenged in the High Court), or someone in the armed forces.

Nabeelah, like hundreds of women without access to public funds under immigration legislation, falls outside of the concession. If she leaves her violent husband, there are no organisations in the UK with a statutory duty to help her.

Cash strapped domestic violence refuges rely on housing benefit, which Nabeelah can’t access. In 2014 Women’s Aid reported that 389 women were turned away from refuges because they had no recourse to public funds. But it is difficult to estimate the full scale of the problem; often insecure migration status is used as a form of control by abusive partners and women face the threat of deportation if they seek help.

If Nabeelah is deported her parents would force her back to her husband. “When I tried to tell my parents about his behaviour,” she said, “they judged me. They said I was wrong. I wasn’t being patient. I wasn’t being obedient. I wasn’t being respectful.”

The Home Office said in response to a Freedom of Information request that it held no central data on how many women apply to have their no recourse status lifted. Nor does government keep a record of how many women are granted temporary support under the Destitute Domestic Violence Concession. This makes it impossible to count the women caught in this protection gap.

Because of the growing number of no recourse migrants – asylum seekers, non EEA migrants, people in the country on a spousal/family visa, foreign students, over-stayers and people with limited leave to remain – councils across the country are developing special units to manage these cases. Outside of the domestic violence rules, other groups with no recourse can access limited public support under the Children’s Act, the Care Act, by proving destitution and under leaving care provisions.

FOIs sent to 34 local authorities in England and Wales, including all the councils who are part of the national No Recourse to Public Funds network, revealed that not a single authority held data on survivors of domestic violence with no recourse. Most responded that they followed existing protocols around dealing with survivors of domestic violence. But this guidance, just as with the Home Office’s latest VAWG strategy, provides no guidance on dealing with women (without children) unable to access public funds and who don’t qualify for the domestic violence concessions.

One local authority employee working in social care who made contact on the condition of anonymity said that whereas 10 or 15 years ago councils would try to support everyone that presented without recourse, recent cuts make this difficult. Since 2010 the Treasury has cut local authority budgets by about 40%, with more cuts expected.

There is no safeguard for domestic violence survivors with uncertain migration status and no recourse

For domestic violence survivors with uncertain migration status and no recourse, there isn’t really a safeguarding mechanism in place. “Local authorities have to admit that they have no policy on how to deal with this. Police and social care have no expertise in this area,” the social care officer said. Services are turning people away because they have no duty to help them under immigration law, but this is giving rise to human rights breaches, she added.

Halliki Voolma is a PhD candidate at Cambridge and is researching domestic violence against immigrant women in Sweden and the UK. She argues that no recourse cases are an example of the tension between human rights and immigration control. In domestic violence cases, states put in place apparatus so that when a woman needs to flee abuse, she can, and her rights are fulfilled. “The no recourse to public funding quite directly takes away those rights from people with a particular status,” she said.

The police arrived and arrested Nabeelah’s husband. Meanwhile she stayed with her friend, while searching for somewhere to live unknown to and far away from her husband and his family (there is a two-year injunction against him, but a family member has contacted her).

Everyone Nabeelah approached, including several domestic violence refuges, turned her away. The first question was always: what is your immigration status? You need to find someone who deals with situations like that, they would say. But Nabeelah was alone with no money or knowledge of Britain’s complex immigration rules. “It wasn’t my choice to come here on a student visa,” she said. “I wasn’t even aware that I was going to be brought here on a student visa.”

She went to the police who sent her to victim support. By the time she arrived Nabeelah was in a state, shaking and crying, fearful of what would happen to her and certain that her husband would soon find her. The interview felt like an interrogation and she a criminal. “I just need a place to live,” Nabeelah said.

After all the questions, she was handed a piece of paper with organisations to contact and told, sorry but we can’t help you, until you get your immigration status sorted.

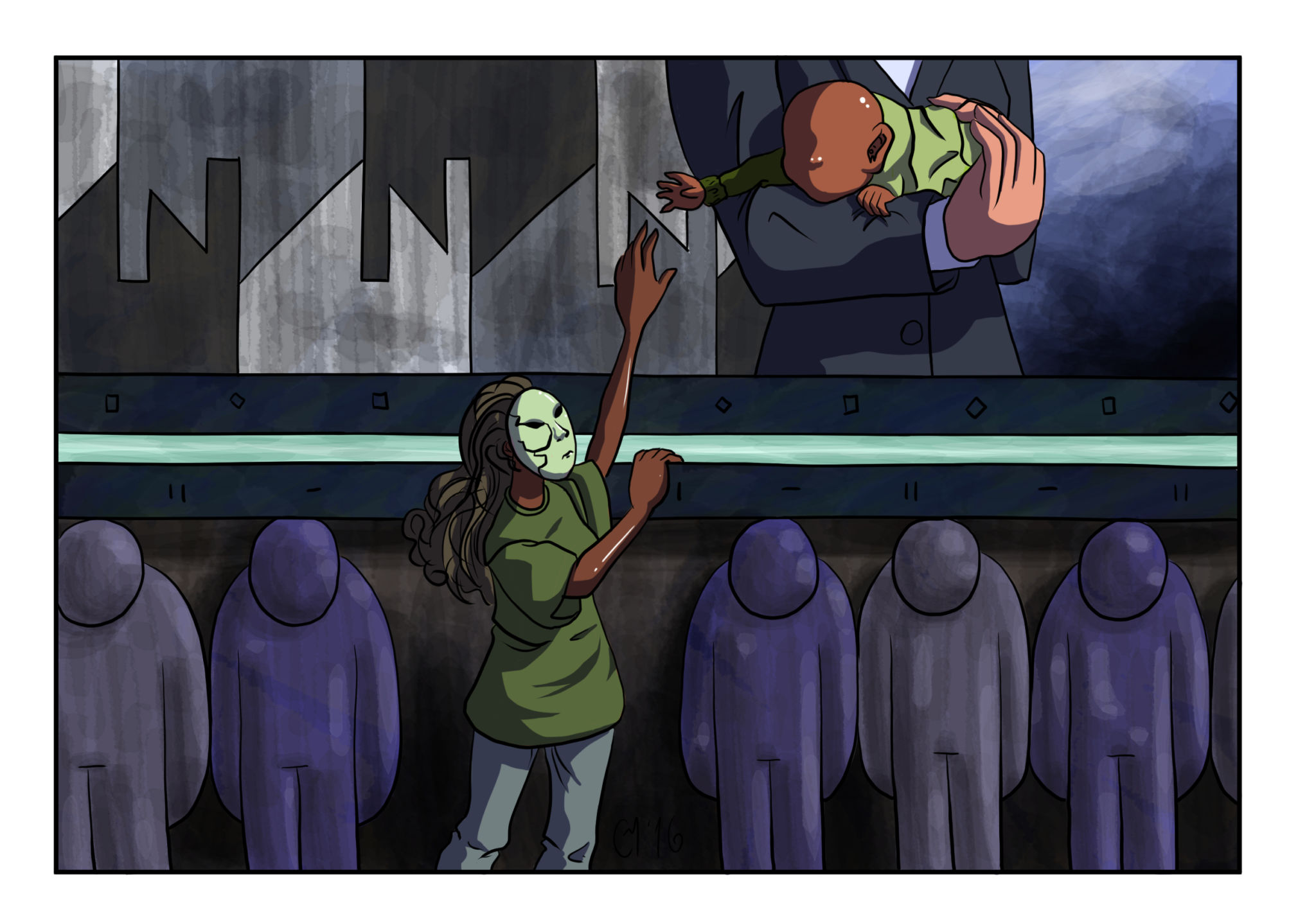

Image by Chris Manson

Nabeelah’s plight isn’t an isolated example. Migrant women across the country who find the courage to leave experience the same barriers.

Kim lives in Manchester and left her British partner of five years in December last year. He’d always been controlling, refusing to help her regularise her status as a way of keeping her dependent on him. When she became pregnant the abuse worsened; he would taunt her and at 8-months pregnant made her sit for hours on a hard stool in the kitchen. She wasn’t allowed to enter the bedroom without permission.

When Kim left, her baby was just a few months old. Despite going to the police, she wasn’t believed. Social services refused to help and she didn’t qualify for housing benefit so couldn’t get a refuge space. Her baby was taken from her and she was placed in a mixed homeless shelter.

There were around 20 men and six women; she stayed there for three weeks. Eventually she came across Safety4Sisters, a Manchester-based group who helped find her new hostel and challenge social services’ decision to take her baby away.

Safety4Sisters was set up in 2008 over concerns about migrant women with no access to state benefits. They realised these women were caught in a trap where they could not escape violence without risking homelessness. They have come across dozens of women affected.

In November 2015 they began the Migrant Women’s Right to Safety project, which runs a weekly group for women with no recourse or insecure migration status experiencing domestic abuse. There is practical support such as sign posting to specialist services, food parcels and emergency travel expenses, but also advice and advocacy. Here Kim met other women experiencing the same problems as her but from a broad mix of backgrounds.

The range of women Safety4Sisters work with indicates that the migrant women affected by domestic violence and denied support is not limited to no recourse cases.

The migrant women denied support is not limited to no recourse cases

Sonya*, a disabled woman, former law student and mother of five, still lives with her violent partner because he holds all the details she needs for her asylum claim. Her husband’s migration status is also insecure and the whole family qualifies for limited asylum support. However, the Home Office pays this money to him as head of the household.

She has tried to apply to the Home Office to separate their joint claim for asylum and to their asylum housing provider to put her name on the tenancy but to no avail. She struggles to feed her children because he controls the money and sometimes disappears with it. She relies on foodbanks and support from Safety4Sisters.

After being turned away by Victim Support, Nabeelah was referred for therapy by her doctor. Her psychologist was shocked at her situation and worried about Nabeelah’s mental health and so vowed to help.

It was through her that Nabeelah was referred to a specialist women’s refuge dealing with South Asian women with a small grant to work with no recourse survivors of domestic violence (their funding has since been cut). Here Nabeelah was referred to Solange Valdez, a legal aid solicitor who then worked at Ealing Law Centre in West London.

Working from the centre’s small high street office, Solange had many clients that fall into this category. A woman from South America who became homeless after being made to leave a refuge when her leave to remain ended. There is the Eritrean woman who came to the UK to live with her refugee husband, then experienced domestic violence. When Solange argued that this woman should be able to apply for indefinite leave to remain under the domestic violence concession, the Home Office said that the concession was only for the spouses of settled citizens, excluding refugees.

When I met Solange last summer, there was an impressive stack of papers by her desk; the messy case of a heavily pregnant Egyptian woman fleeing an abusive husband without access to support. Solange’s work is chronically underfunded, stymied at every turn by Home Office and social service bureaucracy. And there is no legal aid funding for this work, so it comes down to luck whether or not women like Nabeelah are able to access advice. Solange was able to get Nabeelah’s no recourse status lifted temporarily while the case is challenged in court. Nabeelah has nine months leave to remain in the country during which time she can access benefits.

For Nabeelah the brief respite is a relief. At 24 she has lost her family and her peace of mind. She has regular panic attacks and is on a high dosage of anti-depressants to “help me sleep and cheer me up”. The uncertainty around her migration application is tied up with feelings about her husband. “There is a fear inside of me. About seeing that man again. What is going to happen? What is he going to do to me?

“I just want peace. I just want nobody to be pushing me. I don’t want to be beaten up. I don’t want to be treated like I am nobody. If I go back to my parents’ house and obviously they are going to send me back to him. It is really hard living in fear of your life every day and you don’t know what is going to happen next.”

*Names changed to protect identities.

Banner photo by Chris Manson.