Behind the false claims of Trump and Vance that Haitian immigrants are eating pets lies a long history of racist denigration. Philip Kaisary looks back to the Haitian Revolution to understand the longevity and power of anti-Haitian sentiment.

Lock up your Labrador, secure your Siamese. Vote Republican to ensure the safety of your furry best friend. When Trump falsely claimed in last month’s televised presidential debate that immigrants in Springfield, Ohio have been eating the town’s pets he gave credence and airtime to baseless and sensationalist rumors that he and other prominent Republicans had been peddling on social media in the days leading up to the debate.

According to the Trumpian post-truth universe, one of the great food taboos of Western society – the consumption of companion domestic animals for food – has been routinely happening in middle America and it is the Haitians who are at it.

In the days and weeks since the debate, despite a complete absence of evidentiary support and a series of fact-checks (by AFP, Reuters, BBC, ABC, Sky, and Full Fact among others) concluding the claims are false, Trump has repeatedly doubled down and the allegations of pet-eating have become a conduit to the vilification of Haitian migrants more broadly.

On Friday 13 September, for example, Trump claimed at a press conference held on a Los Angeles golf course that, “in Springfield, Ohio, 20,000 illegal migrant Haitians have descended upon a town of 58,000 people, destroying their way of life. They’ve destroyed the place.” And on Wednesday 16 October, at a televised town hall event held in Miami, Trump upped the ante, claiming that Haitians are not only eating domestic pets but “other things too that they’re not supposed to be,” an utterance intended to spark speculation about cannibalism. But for the racist, anti-immigrant mob violence, bomb threats, and other forms of intimidation that Springfield’s Haitian community has endured in the weeks since September 10 (not to mention the further degradation of American political discourse), Trump’s latest outrageous comments could easily be regarded as comical, merely the latest inane remarks of a dishonorable politician. Indeed, the immediate response to the remarks on social media was to lampoon Trump and to poke fun at his preposterous claims.

But an examination of the long history of anti-Haitian sentiment behind Trump’s remarks may prove a more effective form of critique than either ridicule or aghast liberal handwringing.

Protesters marching against Trump’s immigration policies in 2018. Photo by Fibonacci Blue via Flickr.

In North American and European history, politics, and culture, Haiti and Haitians have long been subjected to grotesque racist denigration. It is not an overstatement to say that Haiti generally only features in Western news pages or the popular imagination as a den of evil, violence, chaos, and savagery, or simply as a cesspool. In this sense, Trump’s allegations are nothing new. In fact, we are obliged to trace their origins to the Haitian Revolution of 1791–1804, a world-historical event that has for long been, silenced, disavowed, and denigrated.

Read more: How can teachers begin to decolonise the curriculum? There may be more opportunities than you think…

The Haitian Revolution broke out in the French colony of Saint-Domingue on the night of 14 August 1791, when in a stunning organizational feat, a band of one to two thousand rebel slaves launched synchronized attacks on designated plantations across the colony’s northern plains. The insurgency rapidly gained momentum and life in the slave colony of Saint-Domingue, the so-called “pearl of the Antilles,” would never be the same again. A revolutionary war of independence eventually ensued that resulted in the overthrow of slavery, white supremacy, and direct colonial rule. The events of 1791–1804 in Saint-Domingue consequently shocked the Western world, reshaped transatlantic debates about slavery, accelerated the abolitionist movement, precipitated rebellions in neighboring territories, and intensified both repression and anti-slavery sentiment on both sides of the Atlantic. However, from the beginning, Western culture has fixated on the alleged excessive violence of the revolution and the supposed savagery of the revolutionaries themselves.

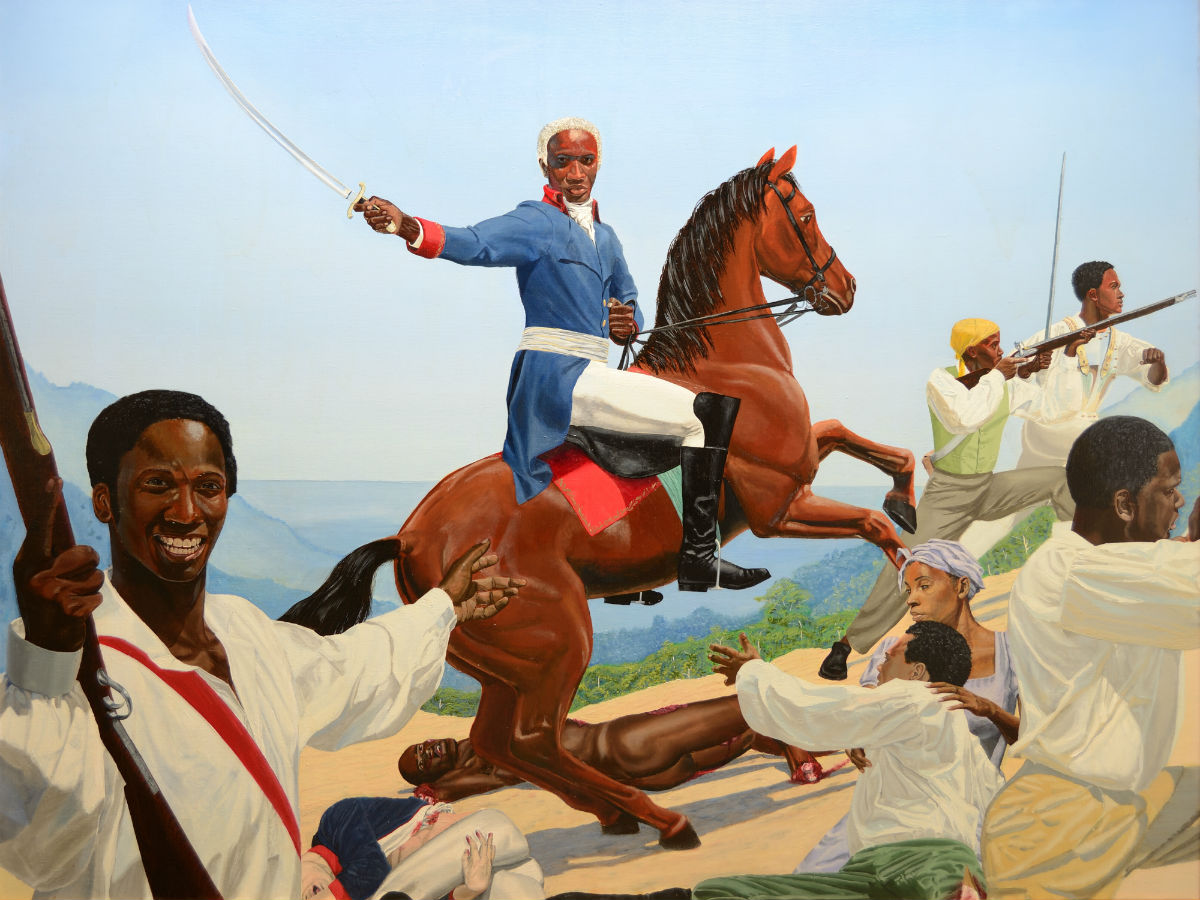

Toussaint L’Ouverture, 2004. By Kimathi Donkor, Courtesy of the Artist and Niru Ratnam, London © The Artist

Notoriously, in 1799, ‘founding father’ and third president of the United States Thomas Jefferson, referred to Haitians as “cannibals of the terrible republic”. And throughout the nineteenth century, Haiti’s revolutionary history was demeaned and exoticized as a barbarous, primitive affair, while Haiti was frequently cited in debates about the capabilities of Africans to live as free subjects. Consider, for example, the opinion of the Scottish historian and essayist, Thomas Carlyle, one of the most revered men of letters of the Victorian Age. In his 1849 pamphlet, Occasional Discourse on the N***** Question, Carlyle expressed his opinion, that Haiti was a “tropical dog kennel and pestiferous jungle”. Now notorious, Carlyle’s statement was very much par for the course for the time.

In the years since, the discourse surrounding Haiti has not changed nearly as much as one might think. Perhaps the most egregious example of anti-Haitian sentiment can be traced to 1982, when the groundless thesis that AIDS had originated in Haiti rapidly gained momentum after a speculative announcement by a physician with the US National Cancer Institute. And in the aftermath of the devastating earthquake that struck Haiti on 12 January 2010, the televangelist, Pat Robertson, claimed that the earthquake was in fact divine retribution for Haiti’s “pact with the devil.”

The photo shows the damage after the 2010 Haitian earthquake measuring 7 plus on the Richter scale. Photo by UNDP via Flickr.

The international media, meanwhile, evoked earthquake stricken Haiti as a desperate land of criminality and barbarism – an evocation which had the effect of propagating long-standing views of Haitian people and culture as crude and “progress-resistant”. Meanwhile, the continued absence of sympathetic portrayals of the Haitian Revolution in mainstream popular culture is an instance of the more widespread marginalization of Black historical achievement in Western culture.

However, Haiti’s presence in public letters and debate has always been an ideological battleground and it has not all been one-way traffic. Beginning in the early twentieth century, this history of denigration began to be contested by a distinguished set of Black writers, artists, and intellectuals. The most renowned of these luminaries includes the Trinidadian polymath CLR James, the Martinican statesman and poet Aimé Césaire, and one of the most influential African American writers of the twentieth century, Langston Hughes. Strikingly, and this brings us back to Trump’s groundless accusation that the Haitians are coming for your pets, the taboo of pet eating has figured in this contested history.

A poem by Aimé Césaire. Photo by dodeckahedron via Flickr.

In the remarkable 1967 book-length poem, A Rainbow for the Christian West, by the Haitian négritude poet, René Depestre, the Haitian vodou gods descend upon the American South in the form of the Black militant poet-narrator who arrives to take his vengeance upon the “Christian West” and to expose its dark underbelly. One of the poem’s most subversive comic-ironic moments occurs when the poem’s narrator claims to be “a great eater” of beautiful pedigree dogs. The effect of this claim is the poetic avenging of the racial stereotyping of Haitians, the recollection of the historical use of slave hunting dogs, and the mocking of the pseudo-science of eugenics-based theories of racial hierarchy (and pedigree dog breeding).

A deep dive into the cultural history behind Trump’s racist, anti-Haitian lies reveals the bigotry and ignorance at the heart of his project to “make America great again”.

The supposedly glorious American past to which Trump seeks to turn back the clock is in fact a past in which systemic terror was waged against people of African descent.

And in baselessly accusing Haitians of pet-eating, Trump drew directly on the discourse generated by that history of racial violence.

Featured image by Gage Skidmore via Flickr.

Read more: