This week Lacuna explores the question of the rights of Mongolian pastoralists in light of huge mining activity in the country, while Philip Kaisary interviews Kimathi Donkor, questioning the London-based artist on the ethics at work in his politically mindful paintings.

Jenny Lander writes of the absolute dependence of a certain few on nature’s day-by-day, season-by-season function as lifeblood. Like the Tuaregs in the Sahara and the Borana in Ethiopia, Mongol pastoralists in the vast and arid Gobi Desert have for centuries relied upon a delicate natural balance to feed and maintain its fertile grasslands, to provide water. As Lander suggests, though, these nomadic herders rely just as heavily on the Mongolian government to honour that dependence, so as to ensure the protection of their fragile equilibrium. Yet the discovery of gold reserves beneath the Gobi sand has led to a lucrative mining drive in the past two decades. Lander points to massive foreign investment that has poured in as a result, to the many mining licenses that have been granted by the government, and to how nature’s balancing act has ultimately been disturbed.

The arrival of large-scale mining in Mongolia has had the side effect of attracting others to the gold, triggering the emergence of an illegal, and particularly dangerous, informal economy. Pastoralists-turned-gold-diggers, unable to obtain suitable equipment of their own, but determined to claim a share, have employed rudimentary mining techniques that are harmful to the little water there is. Desertification, the process whereby desert terrain becomes increasingly arid, is taking place at an alarming rate – and it is not coincidental.

Lander’s questions are many. For how long is the Mongolian government prepared to prioritise huge revenue over the wellbeing of the Gobi and its ancient inhabitants? Is there a balance to be struck between capitalist expansion and pastoralism in Mongolia? And most worryingly: What will be nature’s final judgment on the matter?

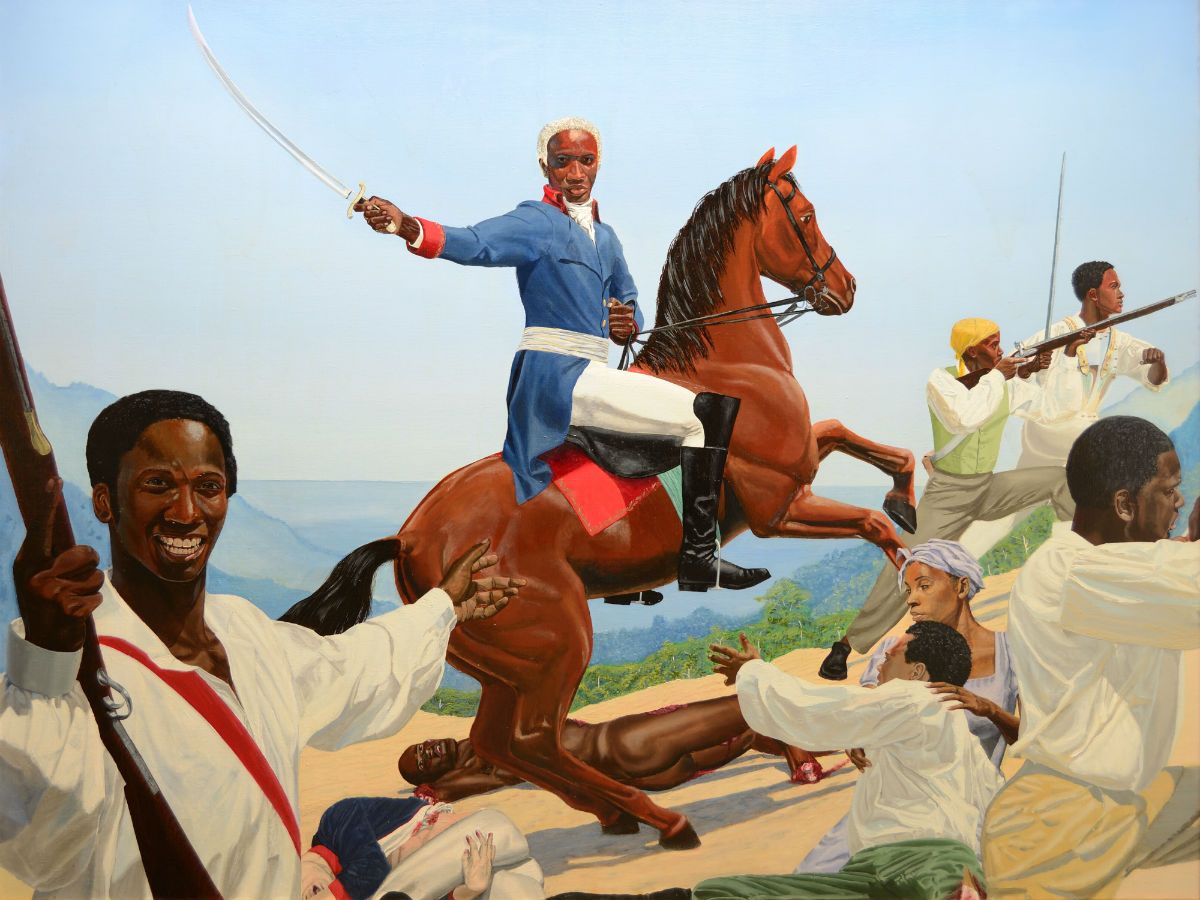

Philip Kaisary, meanwhile, interviews Kimathi Donkor about the artist’s career to date. Donkor’s paintings, which seem to speak always of the interconnectedness of their guiding influences, reflect in turn the complexity of his own identity – not only personally, as the son of Anglo-Jewish and Ghanaian parentage, but in his role as both painter and community activist. How is one to find an appropriate artistic response to, say, the racially motivated murder of a teenager in one’s own community? In other words, to what extent is one able to reconcile aesthetics, politics and downright outrage?

Kaisary questions the very nature of the artist’s vocation. ‘Do you see yourself as a human rights artist? As a didactic artist?’ he asks. Donkor’s response is enlightening, albeit inconclusive. One’s approach to creating a work is always inevitably in need of overhaul, from work to work, for no two subjects will ever garner the same response. Each piece marks the confluence of influences, artistically and otherwise, so that what appears on the canvas is driven both emotionally and aesthetically.

Photo by Sven Zellner