On any given day in Salisbury Cathedral, at least several hundred people, if not more, will make their way to one corner of the medieval Chapter House to gawk at a single sheet of parchment written in a language very few of them can understand. “Moved to tears,” some comment; “What a privilege” say others. It’s almost baffling that this rather plain, rather ordinary-looking piece of old sheepskin can elicit such responses; from everyone, from everywhere, all the time.

That’s because Magna Carta, Latin for the great charter, and 800 years old this month, is a member of that really tiny clique of things, people, and animals that have achieved true iconic status – so much so that it’s enough to say “Wow! I’ve seen IT!”

To be precise, ‘IT’ is actually one of four originals that survive. (There are two others at the British Library and one in Lincoln). And when the four documents were brought together for the first time in London in February this year, around 50,000 people entered a ballot for one of 1215 places to see them. The aspiring ballot entrants were an assorted medley – people who’d studied it at school, people who hadn’t, people living down the road, people from Scotland and Ireland, and from other countries, like Norway, Holland, even Brazil.

While Magna Carta shares its status with Oscar winners, legendary works of art, and celebrities of various sorts, what sets it apart is its power to encourage reflection, and not just any reflection, but a reflection on society, on rights, on freedom. For Salisbury Cathedral, where prayers are offered daily for individual prisoners of conscience, it’s a truly great treasure to have.

Salisbury Cathedral Magna Carta Exhibition. Photo by Ash Mills

Four of Magna Carta’s clauses are still part of English law today, and two of these, the first establishing the supremacy of the law, and the more concise “to nobody will we sell, deny or delay right or justice” are what have made the document a symbol of justice across the world. In 1215, Magna Carta was effectively a peace treaty between the king and his angry barons. Neither side trusted the other and King John successfully got it annulled just 10 weeks later. But then it was reissued, again and again. In doing so, it acquired symbolic significance, as the contract between a king and his people to respect their rights. Magna Carta as an idea flourished and survived.

In putting together a new exhibition at Salisbury Cathedral to celebrate Magna Carta’s 800th anniversary, the challenge was this: How to tell Magna Carta’s story in a way that would make it appeal to a wide range of audiences, many of them casual visitors, with only a bit of time to spare.

Early on, it became clear that it was as much Magna Carta’s legacy as its history that mattered, and while visitors to Salisbury can enjoy trying their hand in a gauntlet, prodding a stretched piece of parchment, or watching a cartoon about the story of King John, it is the symbolism of Magna Carta that impresses them most – its weighty meaning, not its neat miniscule writing on parchment that has been preserved so well. (Though that astounds them).

We started off, in retrospect somewhat naively, by exploring which countries have constitutions reflecting Magna Carta and its values, then stumbled across the realisation that ALL do, no matter how unjust or unfree. We realised that what we really needed to do was present the contrast between the ideal and reality. This is what our new exhibition at Salisbury Cathedral is about.

It starts off with an emotive film about contemporary movements for rights around the world – A reminder that Magna Carta was the outcome of protest, of rebellion. Of course, we had to be careful to ensure that we weren’t taking sides, just reminding people that the struggles for freedom continue, and that political dissatisfaction isn’t only a feature of the developing world. A few have voiced critical comments about the footage we selected, (usually in the form of longish explanations on why one side is right). But surely it’s a good thing that we’ve encouraged people to think.

We thought about the ills that Magna Carta sought to rectify: political oppression, corruption, imprisonment without trial, and set about to present the status of these issues around the world today. The results were surprising, like the percentage of persons in prison awaiting trial in Canada (35.2%) the UK (14.4%) and Libya (90%), or the countries that ratified the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 (China, Iran, Afghanistan, to name a few). And to drive the point home, we created a rotating display of protest ephemera – currently with a collection of items from the Middle East.

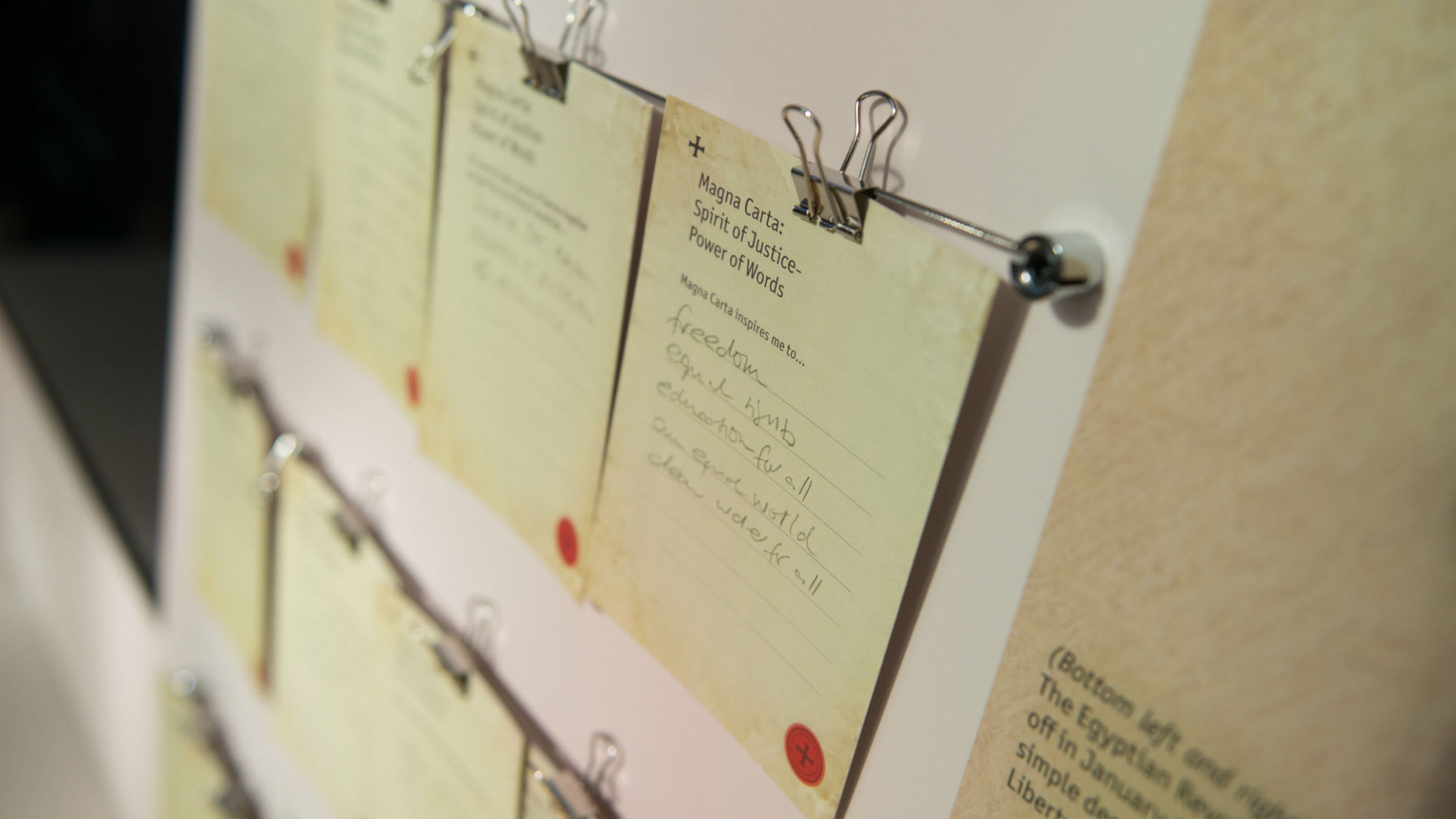

Salisbury Cathedral Magna Carta Exhibition. Photo by Ash Mills

What we have found really effective is to ask people what they would get a group of barons to fight for today. It’s a straightforward yet searching question, because it isn’t the kind of thing most of us think about – defining the one thing we care about most. The answers are wide-ranging, and aside from a small mountain of responses citing peace and equality, many are very specific: ”Better education about politics to encourage everyone to vote,” “Equal rights for sexual minorities”, “A first class health care system for all”, “A maximum wage” and “free wifi,” for example. Animals, the environment, and the earth appear frequently, and often on cards filled in by children: “to save paper in the world”, “to stop poaching” etc. And that’s probably the greatest thing about Magna Carta: that it embodies aspiration, and universal aspiration at that. Five and six year olds with bad spelling and wonky handwriting have as much to say as people writing in alphabets unknown. “Mor Toclot and Iscreem” writes one youngster with an evident sweet tooth!

Visitors (60% of whom are international) are astonished by Magna Carta’s brevity. Lots expect a book; others a long scroll. And what’s even more surprising is that the famous liberty clauses are just two out of 63. A lot of the charter is much more specific, making references to horses and carts, fish weirs, and wood to build castles. “What about women, and those clauses mentioning the Jews?” people ask. Yes, Magna Carta, though ground breaking, was, in other respects, of its time – as much a mirror of social customs in 1215 as about freedom. And what about equality? Well, it’s a milestone, but wouldn’t have applied to everyone originally. Addressed to freemen, its concessions excluded the least privileged. “So why should we care?” A few cynics ask, usually before visiting. Well, because Magna Carta set forth the principle that even the king had to follow the law, and more radically, created a mechanism to enforce his compliance: a council.

So on that one piece of sheepskin is the idea that we, the people, can demand our rights, and that the state is accountable to us. That’s pretty bold for 1215. No wonder we’re celebrating its birthday 800 years on.