Jean ‘sans terre’ Plantagenêt was, at one point, King of England; Lord of Ireland; Duke of Normandy, Aquitaine, Brittany and Gascony; Count of Maine, Anjou, Touraine, Poitou, la Marche, Auvergne, and Périgord; and Viscount of Limoges. Only his English and Irish titles were held in his own right: the rest he held in fief from the King of France, to whom he owed homage.

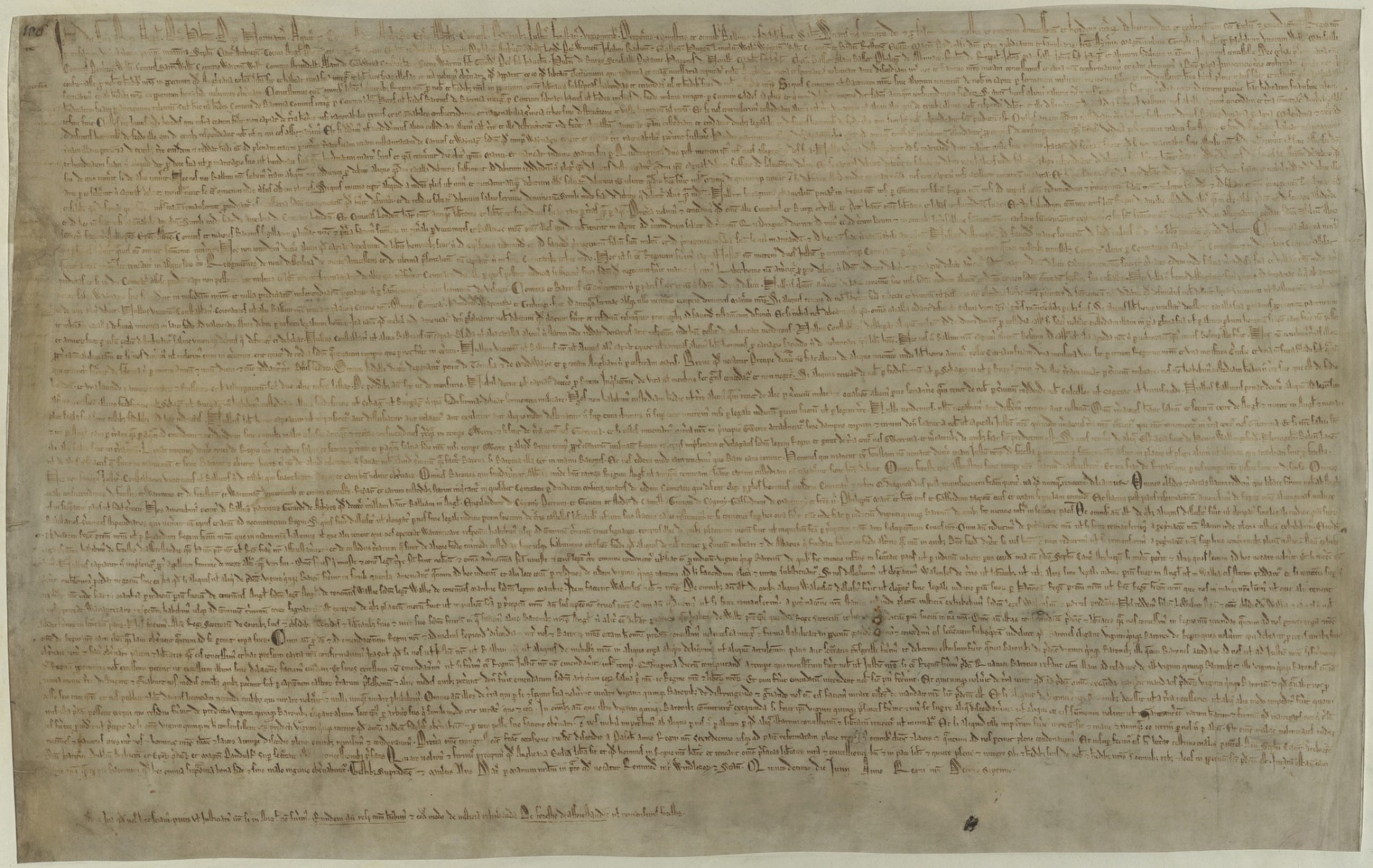

A French-speaking Frenchman of Viking descent, furious temper, and not much luck, le Roy Jean (or, on special occasions, Iohannes rex) is nowadays misremembered as the ‘King John’ who was backed into a corner and forced by his own vassals to put his seal to a ‘Great(er) Charter’, limiting his powers. But just as the political context in which Jean operated—as the combative, conspiring and compromised ruler of an internally diverse and divided land—has been obscured by time and selective memory, so too has the origin and legacy of ‘his’ Magna Carta been obscured by selective (re)interpretation; appropriation; and outright fabrication.

Last Monday—the 800th anniversary of Jean’s ignominy—the kind of jamboree beloved of the British establishment, and particularly its newspapers and broadcasters, took place at Runnymede, attended by the Queen, the Archbishop of Canterbury, and the Prime Minister. A comparison between the Rev Welby’s comments on the day and those of Mr Cameron illustrates the contested legacy of Magna Carta. The Archbishop’s comments were thoughtful, focusing on the Church’s role in the matter and noting Magna Carta’s influence on the United States; its many limitations; and the subsequent repeated failure of both Church and state to live up to the principles which it is imagined the document embodies.

Mr Cameron, by contrast, went full-Whig for the occasion:

We talk about the ‘law of the land’ and this is the very land where that law—and the rights that flow from it—took root. The limits of executive power, guaranteed access to justice, the belief that there should be something called the rule of law, that there shouldn’t be imprisonment without trial, Magna Carta introduced the idea that we should write these things down and live by them. That might sound like a small thing to us today. But back then it was revolutionary, altering forever the balance of power between the governed and the government.

Almost every sentence of this statement is contestable. Let us rewind to get some context.

By 1215, Jean had succeeded in making enemies of Rome, Paris and, as a result, his own barons. Jean had expelled the clergy of Canterbury and seized their property in protest at Pope Innocent III’s unilateral imposition of Stephen Langton as Archbishop of Canterbury, resulting in the Pope placing the whole kingdom of England under interdict from 1209–1213. A kind of temporary mass-excommunication, this formally meant that the churches were closed and the sacraments suspended: no mass, no communion, and no salvation for those who died. The price of readmission to Christendom was for England and Ireland to become papal fiefs, paying annual tribute to Rome. In return, the Pope would aid Jean in his campaign to retake the French possessions which Phillippe-Auguste of France had begun to confiscate (as was his right) in 1204. The plan came to ruin in 1214, at the battle of Bouvines, resulting in what history calls ‘the loss of Normandy’, which was in reality the loss of almost half of France.

Magna Carta must be seen specifically in this light, the light of its time.

For the barons, the fact of the interdict, the price of its lifting, and the failure to recapture ‘Normandy’ made Jean’s rule untenable, and paved the way to Runnymede. Jean had lost the ancestral home of the Anglo-Norman aristocracy and had endangered their very souls in the process.

It is a piece of feudal class-legislation, imposed on one powerful actor by another set of powerful actors in the interests of power. Even the two clauses of general application which remain law to this day, clauses 39 and 40 according to the modern numbering, bear evidence of this:

No freemen shall be taken or imprisoned or disseised or exiled or in any way destroyed, nor will we go upon him nor send upon him, except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land.

To no one will we sell, to no one will we refuse or delay, right or justice.

Far from being general statements of principle (and not applicable to all, the word ‘freemen’ demonstrating the rigid stratification of the feudal system), these were very specific attempts to limit the conduct in which Jean had been engaged for his entire reign. The reference to ‘destruction’ is particularly apposite. In 1199 Jean had consolidated his own ascent to the throne by the capture and murder by his own hand of his 12 year old nephew, Arthur de Bretagne (that is, petite as opposed to grande Bretagne: Brittany), who had been held up as an alternative ruler of the continental Angevin territories by Jean’s rebellious nobles.

There was nothing particularly revolutionary about Magna Carta. Elsewhere in Europe, nobles had periodically forced—or tried to force—weak Kings to bind themselves to law. Besides, within a year Jean had repudiated the Charter and convinced his now-friend, Innocent, to excommunicate those responsible for it. And yet, from this inauspicious beginning, the cult of Magna Carta has grown, leaping across oceans in the process.

Though it is true that Magna Carta’s relatively (and unusually) wide public dissemination at the time helped it establish a grip on the public imagination, the grip was not firm, and it is the Elizabethan and Jacobean jurist Sir Edward Coke who bears the chief responsibility for its modern reputation. 400 years after the sealing of the Charter, it had largely been forgotten, save for its occasional invocation by those who had not (and usually could not) read it. But in seeking to systematise the common law, and, in the process, to uphold the interests of the landed aristocracy, Coke ‘discovered’ in Magna Carta nothing less than a restatement of a ‘Saxon constitution’, dating at least from the time of Edward the Confessor, which had been subverted by the Norman invasion. The fact that Coke had no evidence for this claim was no obstacle, and his ideas were quickly adopted by the Parliamentarians in the English Civil War and the Wars of the Three Kingdoms; extended in the ‘Glorious’ Revolution of 1688; and transplanted across the Atlantic by 1776. The particular American enthusiasm for the Charter is demonstrated by the only monument at Runnymede: an anachronistic eyesore, erected by the American Bar Association.

But let us return to Mr Cameron. The Charter was not revolutionary and it did not ‘alter forever the balance of power between the governed and the government.’ Cameron is right to note that both Gandhi and Mandela made reference to the document, but in this, the two trained lawyers were merely using Coke’s fabrications against the modern bearers of the power he had sought to privilege and justify. Whether the Charter provided much ‘succour to the Suffragettes’, as Cameron put it, is debatable. Aside from predating Parliament by fifty years and democracy by seven hundred, the charter at clause 54 provided that ‘No one shall be arrested or imprisoned upon the appeal of a woman, for the death of any other than her husband.’

Cameron continued:

Magna Carta takes on further relevance today. For centuries, it has been quoted to help promote human rights and alleviate suffering all around the world. But here in Britain, ironically, the place where those ideas were first set out, the good name of ‘human rights’ has sometimes become distorted and devalued. It falls to us in this generation to restore the reputation of those rights – and their critical underpinning of our legal system. It is our duty to safeguard the legacy, the idea, the momentous achievement of those barons.

The reference to ‘Britain’ is unfortunate: for at least 400 years Magna Carta had no more relevance to Scotland than the code of Hammurabi. But the distortion and devaluation of which Cameron speaks is, at least in part, the product of the words and actions of members of his government. The United Kingdom is undergoing a period of constitutional uncertainty. The legal pageantry and verbal flummery of Magna Carta-talk is of no more help to the problems which face it than the very real pageantry and flummery inflicted on the banks of the Thames last week.