Ruth Houghton explains how an exhibition about the “legitimate” Magna Carta in Durham inspired herself and her colleagues to explore how myths about Magna Carta are informing today’s debates about human rights in a number of dangerous and misleading ways.

Over the summer, Palace Green Library in Durham presented an exhibition on ‘Magna Carta and the changing face of revolt’. It showcased the only surviving copy of the 1216 version of Magna Carta, the document reissued by Henry III at the start of his reign. This document was presented as a “legitimate” royal charter, signalling a move away from the rebel manifesto of 1215. The exhibition provided an opportunity for critical reflection on the legacy of Magna Carta and its role in contemporary debates on human rights.

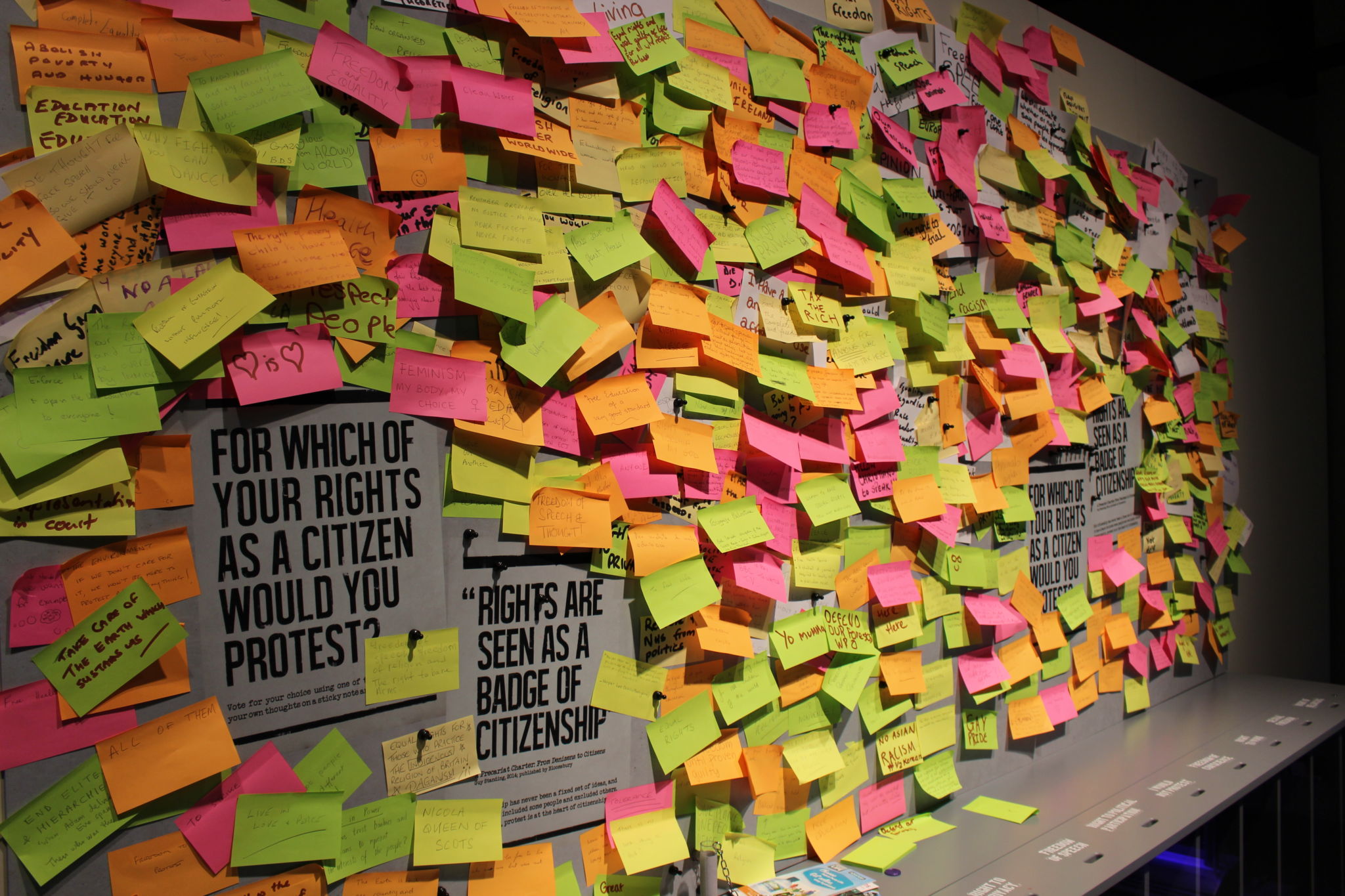

The exhibition took visitors from the 1216 Magna Carta through moments of political contestation in British history: from the Peasants’ Revolt, to the Civil War, to Chartism and into modern day protests. Visitors were prompted to reflect on the legacy of Magna Carta in the displays on Edward Coke, who infamously ‘rediscovered’ the document, and the Chartists’ People’s Charter. A second gallery exposed visitors to the ties between religion, dissent and citizenship during the Reformation. Throughout the exhibition banned books and political treatises, posters from public demonstrations, and artefacts from civil wars, were put on display to highlight the tactics of protest. Even commonplace items (such as gloves, wooden chests and pewter dishes) were revealed as tools of resistance or props in a narrative of opposition. At the end of the exhibition, visitors were asked to vote for the human right they would fight to protect.

When it comes to questions of ‘who’ can protest, the exhibition charted the changing ‘faces’ of protest

When it comes to questions of ‘who’ can protest, the exhibition charted the changing ‘faces’ of protest; it showed a shift from the 13th Century, where the political elites were leaders of dissent, to the protests of marginalised groups, such as the women at Greenham Common who challenged the deployment of nuclear weapons there in the 1980s. But the preponderance of white (and predominantly English) faces raised questions about the universal nature of the rights and freedoms that are supposedly enshrined in Magna Carta. The exhibition did not explore the distinctions drawn between citizens and subjects for people in India, America and other parts of the former British Empire, who over time have used the spirit of Magna Carta to shape their reactions to British rule.

By opening with concepts of citizenship in the Magna Carta, and ending with reflections on the importance of human rights today, the exhibition raised important questions about the relationship between the two. In a sequence of short ‘pop-up’ talks at Palace Green Library, myself and my colleagues from Durham Human Rights Centre explored some of the lesser-known aspects of the Great Charter and reflected on the real legacy of this 13th century document for modern protection of human rights.

Exploding the Myths of Magna Carta

The first question on the minds of many is whether Magna Carta constitutes the cornerstone of human rights in Britain today. According to David Cameron, speaking at the official ceremony in Runnymede marking the 800th anniversary, a UK Bill of Rights (replacing our current Human Rights Act) would enshrine the legacy of Magna Carta. But Dr Alan Greene, speaking at Palace Green Library, on ‘“The Mission Creep” of Magna Carta’ highlighted the limitations of the 800 year old document, and the importance of building upon its modest achievements.

In the 13th Century, the Magna Carta did not protect the universality of human rights, because for the most part it was directed at ‘free men’ (those men who were not tied to land by servile obligations). Unsurprisingly, yet shockingly by contemporary standards, large groups of people were excluded or marginalised. For example, the drafters of Magna Carta were quick to limit Irishmen’s access to courts, which led to the mass anglicisation of Irish names in the late 13th Century so they could appear in proceedings before English courts.

Magna Carta should be treated as the beginning of a conversation on human rights protection, not the finale

Yet despite its feudal beginnings, Magna Carta evolved over time. Greene tracked the development of constitutional and human rights documents across the world, including the US Declaration of Independence, but he noted the persistent struggle for the universality of human rights. For example, the US Declaration of Independence did not extend to native and African Americans. And it was not until the Universal Declaration of Human Rights after World War II that human rights were enshrined as belonging to all people (albeit only in an aspirational document). Steps towards greater protection and promotion of human rights were taken in subsequent international treaties, such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, in regional treaties, such as the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), and in the UK’s Human Rights Act which brought the ECHR into UK law.

It is this evolutionary story about the Magna Carta, which is being celebrated. Can we understand the reverence towards this document as recognition of ‘mission creep’? Its legacy has indeed expanded far beyond its original purposes. Ironically, as Greene noted, the idea of ‘mission creep’ is being used by the current government and their supporters to oppose the Human Rights Act and the role of the ECHR in the UK. But critics have perhaps forgotten that human rights protection evolves and progresses. In these 800th anniversary celebrations, Magna Carta should be treated as the beginning of a conversation on human rights protection, not the finale.

Magna Carta Exhibition, Palace Green Library – © Durham University

The limitations of the Magna Carta are demonstrated clearly by its very first article. Article 1 protects the rights of the English Church. In line with the sentiment of 13th Century England, this provision was not about religious freedom, freedom from discrimination or religious tolerance. In his talk, Professor Ian Leigh highlighted the discrimination of Jewish communities as evidence that Magna Carta did not speak to issues of religious discrimination. The discrimination faced by Jews in the late 12th and early 13th Century was left unaddressed. The expulsion of the Jews in 1219 by Edward I, according to Leigh, is an example of the limitations of Magna Carta in protecting the human rights of religious groups. The fact that the Jewish massacre in 1190 is not mentioned in the Durham Magna Carta exhibition ignores the discrimination faced by the Jewish communities in the years preceding and following the adoption of Magna Carta.

So what does Article 1 provide for in terms of religious freedoms? It addresses religious autonomy, the idea that the English Church should govern its own affairs. Yet, as Leigh noted, this autonomy was not well observed and medieval and early modern history is littered with disputes between monarchs and the papacy in Rome and its English supporters. And in a sense, the question of Church autonomy still causes tensions today, as demonstrated by the debate around same-sex marriage in 2013. Magna Carta did not resolve tensions between Church and State. But it did raise questions which are still relevant today. Its limitations also remind us of the dangers of excluding particular groups from the ambit of human rights protection.

Magna Carta Exhibition, Palace Green Library – © Durham University

The 800th Anniversary celebrations of Magna Carta have given rise to a number of spectacular yet dubious claims about its legacies; for instance, some have argued that Magna Carta signalled the beginning of ‘gay rights’. In his presentation, Dr Henry Jones unpacked a number of Magna Carta myths: it was not a piece of legislation, it failed as a peace agreement, it did not establish trial by jury, and it said nothing of protecting the rights of LGBTI communities. Whilst there were changes to criminal justice in the early 13th Century, for example the decline of trial by ordeal, this was not the result of Magna Carta.

The malleability of Magna Carta myths makes them uncertain and troublesome ground to build human rights protection on

The myth of Magna Carta has been a powerful force in constitutional settlements and discussions on civil and political rights throughout history. However, one of the problems with myths is the extent to which they can be manipulated. In the mid-1600s, the myth of Magna Carta was used by Edward Coke to inspire political changes. In my own talk, I discussed the performances of Shakespeare’s The Life and Death of King John to highlight how the idea of the Magna Carta has been exploited in popular culture (and politics) for nationalistic gains. In the 19th Century, at the height of the French Revolution, King John was rewritten to include references to Magna Carta. Richard Valpy’s production in 1800 used references to Magna Carta as a document that enshrined freedom and liberties to contrast England with French tyranny. The image of England as a bastion of freedom and liberty was, and still is, extolled around the world, often justifying grave injustices in other countries. The malleability of Magna Carta myths makes them uncertain and troublesome ground to build human rights protection on.

Another problem with Magna Carta myths is what they exclude. The prevailing Magna Carta legacy is that of civil and political rights protection, to the detriment of economic and social rights. A notable exception, highlighted by Jones, is that the 1217 Magna Carta and the accompanying Forest Charter guaranteed the right to subsistence. Chapter VII in the 1217 Magna Carta protects the rights of widows to the ‘commons’ and The Forest Charter included rights for peasants, allowing them to take resources from nature. This seems progressive far before its time, given that in 2015 no one is guaranteed a right to subsistence under UK law. Are the rights protected in the Forest Charter of 1217 a progressive project that has been side-lined in how the Magna Carta is remembered by politicians today?

Magna Carta: A legacy

In 2015, the question of citizenship is still hotly contested and the future of human rights protection in the UK remains uncertain. Calling for a UK Bill of Rights signals a rejection of the role played by the ECHR in human rights protection since 1953. Can a Bill of Rights that is faithful to Magna Carta provide the same level of protection?

The exhibition and the pop-up presentations are a reminder that human rights protection cannot be founded on myths. Historical myths around the Magna Carta need to be challenged. This 13th Century document was largely concerned with feudal matters and directed only at a subsection of the population. It is a starting point for rights discussions. But it is not the pinnacle of modern human rights protection.