In 2016, Civil Rights Defenders in partnership with the European Centre for Non-Profit Law completed a study about the legislation and implementation of freedom of assembly in Bosnia and Herzegovina. They discovered that the country faces a wide range of challenges, from non-transparent legal provisions regarding public assemblies to police misconduct and violence, public shaming of protestors, terrorism charges and a lack of police accountability.

In February 2014, an unprecedented wave of mass protests swept over Bosnia and Herzegovina. Hailed as the Bosnian spring, the protests were a political tsunami triggered by an earthquake in the old mining town of Tuzla. What started there in early February as a protest against an epidemic of alleged corrupt privatization schemes became a nation-wide anti-government movement that spread to all major cities.

The protests looked like a turning point. For the first time since war broke out in 1992, it seemed that a protest movement had achieved the critical mass needed to spark tangible political reforms beyond replacing one corrupt government with another. Fuelled by poverty and a sense of widespread corruption and injustice, many protestors were determined to do no less than change the state’s entire political structure.

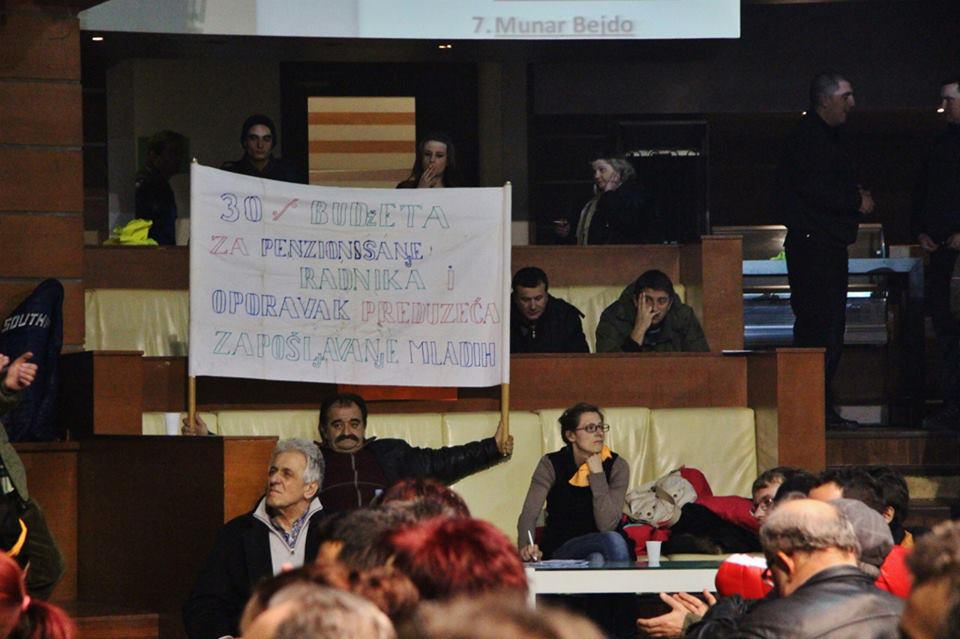

The way in which protestors expressed themselves, shared and exchanged ideas and submitted demands showed that many of them were people who had been neglected throughout the transition processes – people whose disadvantages were related not so much to the 1992-1995 conflict, but rather to the socio-economic transition Bosnia and Herzegovina has faced for the past 20 or more years. Many protestors were former workers – the shiny class of socialist Yugoslavia – whose factories had been either destroyed by war or driven down in dubious privatization schemes.

Now, nearly three years after the protests, it is clear that the movement did not deliver what many had hoped for. While several local governments resigned and citizens organized themselves and formulated demands in plenums for months, the momentum for lasting change did not transform into action. The protests never made significant headway in the Serb-led entity of Republika Srpska and, for a number of reasons, they did not become a political movement capable of challenging the elites in the elections. The October 2014 general elections brought no substantial change to politics and the 2016 municipal elections were tainted by violent rhetoric and political scheming, delivering big victories for the ruling elites. Why?

The protests were a test

The 2014 protests exposed the deep dissatisfaction of Bosnian and Herzegovinians to the quality of life and the frightening absence of future prospects for their children and grandchildren. Because the protests were unprecedented in the country’s contemporary history, they were also a test that uncovered immense flaws in the system that is supposed to protect people’s fundamental rights. The most serious of these violations were manifested in alarming incidents of police brutality against the demonstrators. Together with Human Rights Watch, Civil Rights Defenders documented nineteen cases of police violence against protestors, activists, journalists and bystanders in Tuzla and Sarajevo between 5 and 9 February 2014. Police violence was also documented in Mostar by local activists, as reported in the local media and a 2016 study. Many incidents in cities around Bosnia and Herzegovina have likely gone unreported.

Some cases of police violence came to the public’s attention immediately and further escalated the tensions between the protestors and the police. Aldin Širanović, the leader of a citizen’s group Udar (Revolt) and a central figure in the Tuzla protests that marked the beginning of the nation-wide anti-government movement, was arrested and assaulted physically by a group of policemen in a restaurant. Širanović told Civil Rights Defenders that the beating continued later at the police station, where he was strangled with a Bosnian flag. He said he was held in detention for 32 hours without medical assistance, food or water.

Protestors, some of whom were underage, were arrested in their homes and held in captivity for prolonged periods of time without a just cause. Human Rights Watch interviewed fifteen-year old Zlatan, who said he was arrested in his home in Sarajevo after he posted a photograph on Facebook of himself with name-signs he took from a government building during the protests. Zlatan was held for nearly 50 hours and was not allowed to contact his parents. While in detention, he said he was assaulted physically by the police officers and forced to watch as violence was done to others.

Despite the calls from citizens and local and international human rights organizations, violence against protestors has not been met with much of a response from the police authorities, the government or the judiciary. After the 2014 protests, the Bosnian Security Ministry prompted the independent bodies responsible for investigating irregularities within the police force to react to the allegations. But little was done partly because of the poorly constructed system for dealing with such matters. Citizens’ allegations about police misconduct are investigated first and foremost by the police agencies’ own internal control units, which are largely unknown by, and non-transparent to, the public. A 2015 report on police integrity in Bosnia and Herzegovina by the Pointpulse Network of civil society organizations found that a little over 90% of citizens did not know that the internal controls existed. The same report underlined that the internal controls are not independent, as their leadership is appointed by the heads of the very same police departments they are tasked to oversee.

At the time of the 2014 protests, the police announced to investigate the destruction of public property in Sarajevo as acts of terrorism. This was based on an interpretation of the law that the burning of government buildings was an attack against the constitutional order of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Most investigations of terrorism that followed were later suspended, in part because they were frivolous and widely criticized by human rights organizations and the citizens’ plenums. But terrorism charges were held against two protestors, Nihad Trnka and Salem Hatibovic. They were eventually sentenced to jail for one and two years for criminal acts against the general security of people and property.

Some activists interviewed by Civil Rights Defenders emphasized that spurious terrorism charges have not been limited to the aftermath of the 2014 protests, but have been issued more widely as a means to intimidate people. In May 2015, musician Adis Kušmić was arrested in Banja Luka in an anti-terrorism operation after he had criticized the President of Republika Srpska, Milorad Dodik, on Facebook.

The need for legal reform

The protests in 2013 and 2014 showed that Bosnia and Herzegovina still has a long way to go to assure its citizens and the European Union that freedom of assembly is a fundamental right respected by the police and the elected leaders, and to ensure that authorities who violate that right are brought to justice. There is an evident need to reform and harmonise its currently confusing and restrictive laws.

Currently, Bosnia and Herzegovina has twelve pieces of legislation in place that regulate freedom of assembly and twelve Ministries of Internal Affairs that oversee their implementation. They reflect the country’s complex post-war power sharing arrangement. Several self-governing cantons, have provisions that dictate when and where public assemblies can be held. Civil Rights Defenders found that the city of Mostar, for example, has passed a decision, which allows the police to contain public protests to the University Campus, far away from the public eye.

The laws also allow the police to terminate protests if organizers have not registered the assembly to the authorities beforehand. While the need to register follows international norms, the UN Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Assembly in the Joint report of the Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association and the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions on the proper management of assemblies, has noted that a failure to do so is not alone a good enough reason to stop people from gathering. This is important in Bosnia and Herzegovina, as the 2014 protests showed that the loss of anonymity and fear of repercussions can be genuine concerns for the organizers of protests.

The European Commission for Democracy through Law of the Venice Commission found in their 2010 Annual Report on freedom of assembly that the prohibition of a peaceful assembly on the grounds of failure to submit a notification should be removed in the Sarajevo Canton. The report also concluded that the law should be changed so that the organizers and stewards of assemblies have fewer responsibilities. Currently, the laws give the police the right to end assemblies if they believe that the stewards are unable to maintain peace and order – a responsibility that should belong to the police itself and not the citizens.

Overall, the Venice Commission had a simple message to lawmakers in Bosnia and Herzegovina: laws on freedom of assembly should allow the termination of public gatherings only if they pose a real threat to public safety or a clear and imminent danger of significant disorder. All other rules and regulations, which are currently in place in the 12 laws of freedom of assembly in Bosnia and Herzegovina, amount to little more than distractions that can be taken advantage of by the politicians.

Bosnia and Herzegovina also lacks an efficient institution that can determine whether the people’s right to free assembly is being violated. In theory, this task belongs to the Institution of Human Rights Ombudsmen, but the reality is different. The Ombudsmen (there are three to ensure that each of the largest nationalities is represented) lack financial and political support. In its current form it is little more than an arena for political arm wrestling. As the three Ombudsmen have to reach a consensus in order to issue a recommendation (rarely fulfilled) there is a tendency for no action to be taken.

Overall, the mechanisms for the implementation of the right to peaceful assembly are extremely weak in Bosnia and Herzegovina and there is little to no political will to strengthen them. Human rights organisations have a limited capacity to monitor this right. Still, the main impediment to freedom of assembly is political influence and the lack of accountability of the police. So while the right to peaceful assembly is one of the pillars of democracy, the handling of recent protests and the legal and institutional barriers to the safeguarding of this right in Bosnia and Herzegovina indicates serious gaps in the rule of law and rights of citizens.

For more from Bosnia, join Michaelina Jakala for coffee in the capital, where she learns Sarajevans are still processing events, 22 years after the war ended.

Banner photo by Ena Bavčić.