On an unusually balmy autumn day in 2013, a small group of women gathered outside the nuclear base at Aldermaston and began to sing. All of them had wide smiles and the words came easily.

She goes on and on and on,

You can’t kill the Spirit

She is like a mountain

Old and strong

She goes on and on and on

You can’t kill the spirit

The song was in memory of Jean Kaye. Jean was a protestor, a campaigner for social justice. When she reached retirement age, her convictions took her to the heart of the most intense of peace protests. She died aged 87 last September. By all accounts she was indefatigable, inspirational and extraordinary. She wasn’t the only one.

Thirty years before this little memorial, a much larger group of women gathered outside a US nuclear airbase in the British countryside. They stayed until the American soldiers and the bombs left. It took ten years as the women waged a long campaign for peace and the end of nuclear weapons. The land was Greenham Common; and they would become known as peace women.

The peace women maintained a constant presence at Greenham Common, a patch of grassland in Berkshire, for nineteen years in total. Once the Americans left and the bombs were gone, women stayed until the land was formally returned from the military to the people.

For the women involved, the Greenham Common peace camp was transformative, akin to the feminist liberation movement of the 1970s. It was about more than peace. It would mutate from a single-issue protest against the siting of American Cruise missiles in Britain to a general movement of women who felt keenly the lacuna in the public space for women’s voices.

The camp attracted astonishing numbers from every walk of life; for some, here was a corner of England, just for women. The location, outside a military base for storing nuclear bombs, added to its magnetism. This was not a women’s group hidden away in places where women were permitted to gather; at Greenham Common they were visible, disruptive, and loud.

Women went to Greenham to protest against nuclear weapons and left liberated. Greenham Common is a story of one protest and it is a story of many, a movement of individuals, each grappling with their own inner battles. It is the story of a protest that created a generation of women ready and willing to commit their lives to challenging social injustice, whether through non-violent direct action for the disarmament of nuclear weapons, the campaigning for the rights of disabled children or providing practical support to refugees. Thirty years on, its legacy is still felt keenly by those involved. And that is an important element of any protest: that the people who have the courage to stand up and take action transform their own lives, as well as striving to transform society. Remembering their stories is then a vital issue: remembering people like Jean Kaye and those other women of Greenham Common.

Part 1 Embrace the Base

One frosty December morning in 1982 several hundred coaches trundled along the M4 motorway linking London and South Wales. The coaches, converging from every corner of the British Isles and beyond, carried thousands of apprehensive women. Motorway cafes across the country began to fill with them, each feeling a pleasant jolt on realizing she was not alone.

‘It wasn’t until we got to the Severn Bridge that we started noticing the other buses. There were just so many women everywhere. We got to services and the whole place was taken over,’ says Diane Richards. Her friend Jo Engelkamp nods, misty-eyed as she recounts the event that changed her life: ‘We were coasting down the motorway… and buses and buses of women were on all sides waving. It was amazing.’

Thirty one years later, in a living room in Aberystwyth, Wales, a group of women pour over photos, sharing tales, and exclaiming over old bits of barbed wire fence. Jo, Diane, and their friends all attended Greenham Common at different times during the 1980s. But they were all there for one particular event: ‘Embrace the Base’.

They were among several thousand women who received a letter urging them to join a mass action on Sunday 12 December 1982 at an American military base deep in the British countryside. ‘We have one year left in which to reverse the government’s decision about Cruise missiles. There is still time to stop them,’ it read.

Exactly three years before, members of NATO agreed to deploy hundreds of American nuclear warhead carriers and bombs across Europe. The fear of ‘mutually assured destruction’ had begun to fade as countries refined nuclear weapons so that bombs could fly quicker and further and strike ever more accurately. The USA and Russia, their allies in tow, jostled to position themselves to strike first and destroy the enemy’s weapons before the other could retaliate. The British government agreed to host 160 Ground Launched Cruise Missiles for the Americans; 96 at RAF Greenham Common in Berkshire and 64 at RAF Molesworth near Cambridgeshire.

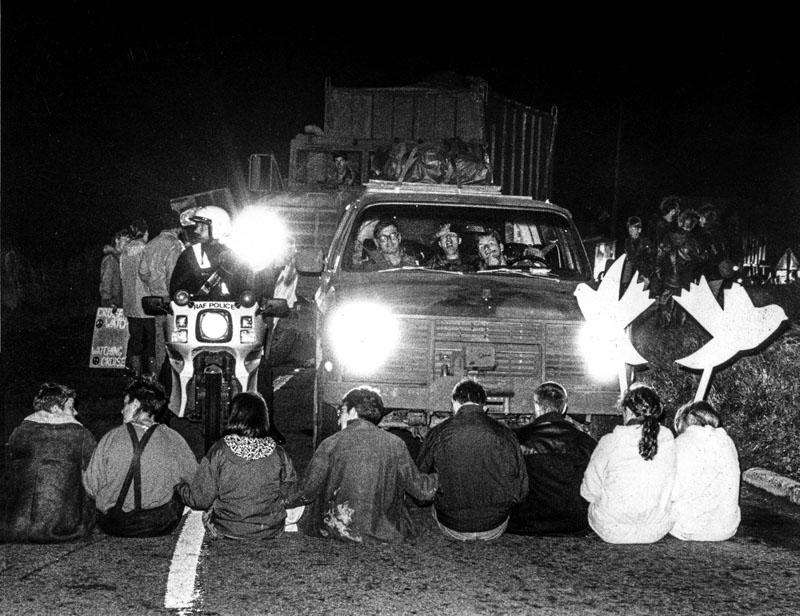

Embrace the Base: Women protest at Greenham Common USAF American Airforce Base from which cruse missile launchers were deployed.

© John Harris/reportdigital.co.uk

By the time the women arrived at the Greenham Common military base that Sunday morning in 1982, the towering concrete silos to store the missiles were already in place.

The women were told to arrive early and be as ‘self-sufficient as possible’. Bring warm, waterproof clothing, food, sleeping bags, blankets, and if possible a tent. The organisers would provide legal advice and some non-violent direct action training. Men could attend, but not as part of the action. Instead they would be required ‘to help with food and childcare’. The letter ends: ‘If every woman copies this letter and sends it to 10 friends and they each send it to 10 others, then we shall be THOUSANDS. Each woman is like a spring who together with others becomes a stream, a river, an ocean.’ The idea was to encircle the base, to embrace it.

Women of every age responded, finally reaching the base to trudge through mud and dense woodland, wrapped up against the chill, daughters, mothers, wives and grandmothers, to attach their personal mementos to the 9-mile barbed wire fence surrounding the airfield. They brought teddy bears, clothes, baby blankets, tiny children’s shoes, tampons, balloons, ribbons, family photos, and a web of fluorescent wool, all were threaded through the dull wire.

‘Someone had woven an amazing sculpture out of dead leaves and twigs. It looked like pictures you see of humans after nuclear blasts, almost the shadow of a person. They had woven it into the fence, it was incredible,’ says Lynn, who hitchhiked to the protest from Nottingham.

‘I was looking after my children,’ she says, ‘and taking whatever time I could, to get to the places I thought I should be.’

Helicopters circled the skies, their din competing with the growing excitement and audible wonder as women looked around and saw not a handful of protestors, but tens of thousands of women.

‘I remember huge whooping and cheering. It was bigger than anyone thought it would be. I remember feeling high and buzzing. All these women together,’ says Liz Davies, a London-based housing barrister, who went along as a student because, ‘it just seemed obvious. It was part of my normal political activity’.

Then everyone held hands. Thirty thousand women formed a human chain, encircling the monstrous silos; enclosing the symbol of everything they opposed. For many, it was a moment of physical power and joy. Some women began to shout; the exhilaration rippled along the chain and a wave of howls and shrieks echoed across the base.

Pat Richards, a retired schoolteacher from Aberystwyth, sits up straight and shakes her head in wonder, as if still in shock.

‘I thought the thing would disappear,’ she says. ‘I felt like Ginsberg at the Pentagon … I really thought it was just going to go. We were making all this noise towards this terrible thing.’ Her friends laugh, but their eyes too are bright, full of remembering.

As dusk settled on that day in December 1982, the women fell away from the base, their emblems of hope clinging to the fence, leaving thousands of small candles flickering on the ground

On Monday, the next day, the police turned violent. Most women had gone home, but a few thousand stayed to stage a mass blockade around the perimeter of the base. They were dragged, shoved, and kicked; policemen lifted the women, singing defiantly, away from the fence. Some clung to the wire, only releasing their grip when other women stumbled forward to take their places. This went on for several hours; many women were arrested. Bruised and exhausted, the Greenham Common peace women, as they were now known, remained steadfast.

In contrast, the beginning of the Greenham Women’s peace movement was a much quieter and far less fraught affair. It started with a ‘walk’ from Wales to England; 120 miles during the hot summer of 1981 from Cardiff City Hall to the Greenham Common military airbase in Berkshire.

Photo by Lesley McIntyre

The ‘walk’ took place during a time of fear. Nuclear weapons had been ‘off the political agenda’, at least as far as the general public were concerned for quite a while. Public support for nuclear disarmament probably reached its height around 1963, according to the political scientist Hugh Berrington in a 1989 study on British Public Opinion and Nuclear Weapons.

Membership of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) had declined dramatically since the days when it commanded tens of thousands of passionate protestors on its Easter marches during the late 1950s.The Labour Party leadership had long rejected the 1960 party conference motion supporting unilateral disarmament. The nuclear bomb may still have been an issue, but it was one being dealt with on foreign shores and behind closed doors, far from the daily concerns of the British public.

But by 1980 the possibility of US nuclear weapons arriving on British soil and carted along country lanes for regular testing provoked a strong reaction. Public opinion, while not in favour of British disarmament, was set against the deployment of America’s nuclear bombs in Britain. CND saw an astonishing growth in membership from about 3,000 in 1978 to around 350,000 in 1984. At the Labour Party’s 1980 conference, the call for unilateral disarmament resurfaced and was eventually, amid much controversy, included in the party’s 1983 manifesto. For a time, British people genuinely feared a nuclear war. A BBC poll conducted in 1980 found 40% of participants believed nuclear war possible within 10 years; in a Gallup poll in January of that same year 57% thought a world war imminent. Also in 1980, the New Scientist magazine reported that 300 firms had begun marketing nuclear fallout shelters and radiation suits.

The government’s release of Protect and Survive broadcasts and pamphlets did little to allay fears. The advice, which ranged from ‘close the curtains’ to ‘stay inside under a table’, seemed absurd when considered alongside images of the devastation at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. ‘You were made to feel utterly powerless,’ says Pat. ‘What were we to do – whitewash the windows? It was ridiculous!’

Ann Pettitt, living in an old farmhouse with her two young children and their father in rural Wales, felt fear too, but her overriding emotion was anger.

‘I remember looking at my two children, bright-eyed and muddy, and trying to think about the future – it was like looking at a solid wall, with no chink of light, no windows or doors. I began to aim punches at the wall,’ she writes in her memoir, Walking to Greenham.

The hopelessness was widespread and indicative of a population denied access to the closed world of nuclear power, where even senior politicians appeared beholden to foreign leaders, faceless nuclear scientists and defence contractors. Pettitt wanted to ‘gatecrash the closed world of media debate on defence issues’ with a march from Cardiff, where there was a nuclear development factory, to Greenham Common, where most of the Cruise missiles would be deployed.

Pettitt enlisted three like-minded women: Karmen Thomas, Lynne Whittemore, and Liney Seward. They set about organizing a female-led march to protest against the decision to accept Cruise missiles. They promoted it in places where they were certain to find allies such as Peace News, but they wanted to galvanize popular opinion too so placed ads with Cosmopolitan and other women’s magazines. Even so, the women found it hard to enlist support. One feminist campaigner questioned whether they would be able to walk twelve miles a day without proper fitness training: couldn’t they plan local peace picnics instead? CND initially rebuffed their request for £250 to help with costs.

Undeterred, on 26 August 1981 the women set out. In her book, Ann describes the four women succinctly: ‘poor, had no powerful connections, were burdened by the care of very young children in rural isolation’. But they were well versed on the nuclear arms race and the effects of a nuclear explosion. They called themselves ‘Women for Life on Earth’.

Soon, they were a group of around forty, mostly women, a smattering of children, and a few men. ‘Simply to discover that this prim-looking grandmother, this cheerful G.P., this nervous schoolgirl, this single-parent mother of five, took the threat to our future seriously enough to respond to a call to action coming not from any known organisation but from an unknown individual living in an obscure rural corner of these isles, gave us courage,’ Ann recalled three years after the march in an issue of the Greenham Factor, a peace pamphlet published in 1984.

Adorned in purple, green, and white suffragette scarves, they marched, stopping to speak at meetings and hand out petitions. They camped in church halls and relied on the hospitality of sympathisers. The moments of despair came when journalists refused to cover the protest because peace ‘was last year’s story’. A sense of pointlessness crept in and led to purchase of three metres of chain and four small padlocks. It’s what the suffragettes did, they told themselves. If we chain ourselves to the gate of a military base, surely they can’t ignore us?

On seeing the women, aged between twenty and sixty, their long billowy skirts disguising chains, huddled close to the main gate outside the Greenham Common military base early on the morning of 5 September 1981, the guard assumed they were cleaners: ‘Aren’t you a bit early?’

Despite their anti-climactic arrival, they felt impelled to stay. The initial protest went ahead with speeches and singing, but their request for a televised debate on nuclear weapons with the Secretary of State for Defence was ignored. There was little coverage in the media; it looked increasingly as though the Women for Life on Earth’s 120-mile march had made little difference to anyone, anywhere. Their frustration mounted when journalists did eventually turn up; they were usually only interested in pictures of women chained to the base fence, which were then published with amusing captions and no report explaining why they were there. Fed up with being denied a voice, the women chained some dolls to the fence instead.

A CND rally in Hyde Park, held a month later in October 1981, provided an opportunity to boost the campaign. Once again the women turned to CND for help. Its response was non-committal. Ann wrote, ‘They [CND] just didn’t think that a bunch of women camped outside Greenham Common airbase, protesting at the notion of ‘Cruise’ missiles, was all that interesting or note-worthy.’ Ann found a sympathetic CND veteran who suggested one more march in order to ‘earn’ a two-minute slot at the rally.

So they marched again, this time from Greenham Common to Hyde Park. It was miserable. Both Ann and Karmen had to take their young children with them; it rained for most of the 50-odd miles. Along the way, Ann battled with a growing sense of futility. She couldn’t stay at Greenham Common for much longer; her children and sick father needed her attention. But how could the peace camp end without penetrating the public consciousness, without forcing people to at least question, if not reject, Cruise missiles? On this grey march, Ann found solace in Andrew King, a Catholic priest, who had offered support to the marchers. He told her:

‘What is planned for Greenham is the deployment of weapons of an evil nature. An act of great evil is planned for that place, and it is better to stand before it simply as a silent witness, even if there is only one person there, than to walk away and pretend not to know.’

The words buoyed Ann as she faced the huge crowds in Hyde Park and begged for their help. An hour, a day, a week; the length of stay was irrelevant. They just needed women to go to Greenham Common and bear witness.

Her call to arms worked. Women flocked to Greenham and stayed, preparing the ground for the mass protest of the ‘Embrace the Base’ event.

Part 2: Bring your black cardigan

A few weeks after women encircled the base at Greenham Common, 56-year-old Hazel Rennie stood in her local supermarket. It was Christmas Eve 1982. As laden trolleys passed her by, Hazel’s thoughts strayed from the supermarket shelves to the ‘ghastly things going on in the world’. That was when she made up her mind.

Thirty-one years later, Hazel bounces about her sofa, using her arms to conduct her memories. ‘All this peace and love. I knew that the best place for peace and love was at Greenham.’ For a moment, Hazel, whose tiny frame seems perpetually in motion, is still. She frowns in concentration, searching the ‘big black hole’ for the words and her memories; her grey bob dips to her chest. When she looks up again and leans forward, chuckling, her expression is a mix of triumph and mischief.

‘I told my husband and two sons “I am going to go to Greenham Common for Christmas”. They weren’t too pleased, but they did support me. I looked in the Observer magazine, and it showed a signpost with all the different places on it. The nearest one was Newbury.’

Armed with some brandy and a sleeping bag, off she went.

Hazel knew she had arrived at Greenham when the bus driver said, ‘Any of you ladies want to hold hands, get out here.’

Hazel hopped off the bus, marched along the road till she came to a grassy, muddy patch where she found a clutter of tents, worn sofas, old shopping trolleys, and women of all ages. ‘I sat myself down and that was it, I was at Greenham, just like that.’

Hazel Rennie: “I became myself at Greenham, I was a simpleton before that”

For two weeks Hazel immersed herself in camp life, thinking, debating, fence cutting, and walking the perimeter of the military base. ‘I became myself at Greenham. I was a simpleton before that,’ she says. ‘I learnt so much.’

Hazel could not stay full time. During the week she worked as a carer in an old people’s home. But after that initial introduction, she was a frequent visitor. Greenham quickly became the window through which Hazel observed society’s most pressing problems.

‘We thought we were going to change the world through Greenham. What we did was to politicize women who had never been on a demo before.’

Hazel’s words begin to flow and reveal a mind still alert to social injustice. She relates the struggle of Greenham women to battles facing women today. ‘Women are beginning to realize that they can take over. It will be some time, but they will. They have to. I think that women have been too easily won over. Women must achieve and show that they can achieve.’

Much of Hazel’s own protest at Greenham was physical. The slight grandmother would use her presence in whatever way was possible to block or disrupt military activities at the base. The peace campaigners at Greenham Common were wholly committed to non-violent protest, but each individual woman defined the point when her actions became an act of violence as the ‘Black Cardigan’ action on Halloween in 1983 showed.

The operation took months to plan. Women living permanently at the camp travelled across the country to recruit other women for a ‘Halloween Party’ at Greenham Common.

Protestors were told to bring their ‘black cardigans’, a code name for bolt cutters. The days leading up to Halloween were spent clipping the strip of holding wire at the top of the perimeter fence. It took several attempts before the heavy bolt cutters snipped the barbed wire encased in a thick layer of plastic.

As the day faded on 29 October, around 2,000 women quietly began cutting the nine-mile fence. The women were two or three deep along a five mile stretch of the grassy verge outside the barrier. There were not enough cutters to go round, so women without them gripped the wire and began to rock the fence gently, pushing and pulling, till it loosened. The Ministry of Defence guards stood inside the perimeter watching the women, impotent and horrified as half the fence collapsed at their feet.

Sarah Hipperson was one of the organisers of the event. ‘It was a bit of scandal that women used bolt cutters,’ she says. ‘It was a very successful action, they took us seriously thereafter.’

A few days later, defence secretary Michael Heseltine, said in an interview that protestors who entered guarded areas of the base could be shot. An Associated Press report dated 2 November 1983, reported the minister saying: ‘The difficulty is that you can’t tell the difference between a terrorist and a peace protestor if the terrorist has taken the trouble to make himself look like one.’ It was a thinly veiled threat; continue getting in the way and you might be mistaken for terrorists.

The women stayed put even with the possibility of violent retaliation from the government. They continued to enter the base and cut the fence, actions that riled the Ministry of Defence, and caused security costs for the airbase to spiral.

Throughout this time, the women maintained an ethos of non-violence. But using bolt cutters had divided the peace camp. Some women argued that to use them was an act of violence in itself and undermined the non-violent aims of the movement. Others believed that violence against property didn’t count.

Though they might all have opposed violence, it couldn’t be escaped. The women faced it time and again usually in the form of a bailiff’s rough blow or police officer’s boot. Fingers were stamped on, ribs broken, heads smashed against concrete boulders. There were random attacks too, usually at night, from members of the public. One woman described being woken up as half a dozen men landed on her tipi. Another recalls cars driven on to the camp while women slept inside their tents.

The violence was indiscriminate. One night Hazel and a fellow camper were badly beaten. Jennifer Engledow, a friend of Hazel’s, was at Greenham when the attack occurred. ‘The lights went out where they were camping,’ she says. ‘They were watching the silos. These two people came and beat them up in the middle of the night. Then the lights came on afterwards. Hazel had a couple of ribs broken. She is tiny; she is not a big woman. They were just the two of them sitting there quietly talking. I was horrified that anybody could do that to two women sitting there, saying they want peace.

They were attacked in the middle of the night.

The violence inflicted may have been difficult to take but it focused some thoughts on the nature of the women’s protest and its wider relevance.

Rebecca Johnson, who lived at the camp for five years, says, ‘We were developing our own non-violence. We were making connections with women in the community, disadvantaged women, women who had suffered a lot of violence, because it was a place to explore non-violent ways to deal with violence. We weren’t just a protest against nuclear weapons, we were actually building a community that was tackling a lot of other issues.’

The physical fact of violent confrontation in their protest helped define the women’s interpretation of non-violence as active and intensely political. This was not turning the other cheek; it was a dynamic process of voicing discontent. ‘I am committed to non-violence. That doesn’t mean I am passive. Non-violence is very active and has to be aimed at making change,’ says Rebecca.

They blocked military vehicles and occupied control offices. They climbed and cut the perimeter fence, and marked vehicles that would be used to carry Cruise missiles. And they sang. Often the women’s peace songs were a way of staying calm and confronting violence during mass protests. They also helped lift spirits, binding them to one another. They sang old strike songs, civil rights and anti-war anthems, and their own Greenham peace songs.

Cor Gobaith choir (Choir of Hope) made up of Greenham women and peace campaigners singing ‘Bread and Roses’, originally sang by women workers striking in America in the early 1900s.

In 1983 the tide of public opinion began to turn against the Greenham women leaving them exposed and vulnerable. In the after-glow of the Falklands victory, Margaret Thatcher was re-elected, convincing the voting public that Cruise missiles and the development of Trident were necessary to face the Soviet threat.

Public hatred of the peace women intensified. They became used to people shouting ‘fucking lesbians’ and gifting them broken bottles and bags of faeces. The women were barred from local shops, cafés, and Little Chef. One greasy spoon in Newbury hung up a sign: ‘No peace camp women here’.

One greasy spoon in Newbury hung up a sign: ‘No peace camp women here’.

There was little to protect the peace women, who continued to take huge risks with their protests. The story of Ann Harrower showed just how vulnerable the women were.

Ann and a few other women were camping by the side of the road not far from the airbase, when a procession of five US military vehicles came into view. The first car passed and several women jumped into the road to ‘register a protest’, moving out of the way before the vehicle reached them. They repeated this for the third vehicle; one woman jumped into a verge, and Ann moved ‘well over’ to the opposite side of the road. Instead of continuing in the correct lane, the vehicle swerved towards Ann into the oncoming traffic lane, knocked her down and drove off. The second two vehicles followed without stopping.

Ann’s leg was ‘crushed’ in the incident, according to the report written by a CND officer based on testimonies from Ann and other Greenham women. The report concludes: ‘The view of the women is that what happened was not merely negligent driving but a deliberate attempt to knock someone over.’

The Guardian newspaper also reported the story. ‘A woman peace campaigner was injured yesterday after attempting to stop a US military convoy leaving RAF Greenham Common, the Cruise missile base. She was hit by a trailer and taken to Basingstoke hospital with a broken leg. A Ministry of Defence spokesman said that the woman was one of a number of protestors lining the road outside the airbase and that she threw herself between the last two vehicles of the US convoy. Thames Valley police are investigating.’

The women camping at Blue Gate, one of the busiest entrances to Greenham Common, wrote their own account in a letter to a senior USAF official at the base. They said that five US Dodge Rams drove along the Burysbanks Road escorted by RAF motorcycles. Three women from Blue Gate moved towards them. ‘Instead of slowing down or attempting to avoid them in any way the US vehicles speeded up charging the women.’ Ann couldn’t get out of the way and was hit and left in the road with a ‘badly damaged leg’. ‘We know that the US army in the UK is outside the law of our land when driving our roads, but such behavior in peace time is still a crime,’ the letter says.

A few months later, the US Department of Defense, sent an end of year letter to all employees of the 501st Tactical Missile Wing, which had been set up in 1982 to operate Ground Launched Cruise Missiles at Greenham Common. In the letter, written by Lieutenant Colonel David Mills and Wayne H. Cox, a USAF manager, the unit is congratulated for a successful year. In among praise for sporting achievements, a picnic, promotions, and the arrest of 400 peace women, is a brief reference to Ann. ‘The Greenham bylaws went into effect, the superfence was constructed and we hit one peacewoman with a vehicle.’ The letter ends: ‘It has been a productive year. You should be proud of your accomplishments.’

On 16 January 1986, Paddy Ashdown MP, wrote to the then Home Secretary Douglas Hurd: ‘I hope you will agree with me that the tone of this letter is utterly disgraceful and seems to indicate that the US Airforce Security personnel at Greenham Common treat as a matter of competition and achievement, the injuring of British subjects.’

Though there was a police investigation, Thames Valley police did not prosecute the driver responsible for Ann’s injuries.

Engulfed by increasing public vitriol, the women turned inwards, many forming lasting intense relationships. Bonds developed, unquestioning, sometimes reluctant, but necessary.

The camaraderie was essential to the protest and the longevity of the campaign. Lynn remembers,

‘People did get down (and) depressed. But the support system was amazing. There were always people there to give you a hug and see you through your tears. We all cried.’

Without this solidarity, the peace camp would have collapsed. Without it, it would not have survived living with the rain that turned to sludge the ground where they slept or the biting cold during winter.

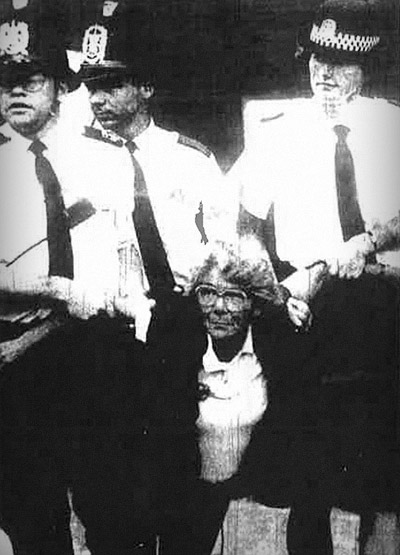

Jean’s arrest at Portsmouth Arms Fair, September 1991

A number of quiet, unassuming women were crucial to maintaining these bonds. In the spotlight, there was always a handful of eloquent women, capturing the eye of the media, and instigating the most daring actions, balancing on the tip of the movement, while behind the scenes these stalwarts provided hugs, lifts to court, blankets in the winter, and daubed bruises.

Hazel had her resolute supporter to help her up, and dust her off, so she could begin again. That was Jean Kaye.

‘She was always calm. I don’t think I ever saw her angry. Well, she was angry about what was going on in the world,’ says Hazel. ‘She was an important woman. She just tapped at my shoulder, just a step behind. She is one of the most important women of Greenham because she is always at your shoulder if you need her. She never made a song and dance about anything she did.’

Jean Kaye fills the memories of many a Greenham woman, reliable and unexpectedly daring. She was also one of those women who went to Greenham to campaign against nuclear weapons and left ready to change the world.

Part 3: Pankhurst calling

Stefan Kaye’s flight from Cambodia landed in England the day before his mother died. Jean’s health had been ailing for a few years, and though it was a good decade or so since she was last thrown out of Parliament or had been shackled to the US Embassy railings in London, the 87-year-old peace activist battled on.

No longer able to climb the trees and fences that concealed nuclear development sites dotted about the English countryside, she still attended monthly peace camps. Jean’s fruit crumble fuelled her fellow campaigners and her polite convictions provided succour for many an encounter with a petty guard or angry passer-by. Out canvassing people in Newbury about the nuclear activities on their doorstep, people would often shout, ‘Get a job’. Of all the jibes the women received, only this rankled Jean. She would shout back, ‘I’m 75 actually and I have worked all my life and brought up four children.’

Jean Eleanor Sherbourn was born 30 April 1926 in Witney. Her father was a rail porter on the line that went from Oxford through to Witney and then onto Gloucestershire. Her mother left school at 14 to work in the local blanket factory. Their second daughter Jean was bright and, age 11, won a county junior scholarship place at Witney grammar school.

Jean aged 14, second from left, with her sisters Elsie, Margaret, and Rosemary.

In 1949, she met Franciszek Krząkała, a young Pole who had found his way to Britain at the end of WWII, while they were both potato pickers in Essex. They married in 1951. Her husband changed his name to Francis Kaye: it was easier to pronounce.

For the next 30 years, Jean Kaye’s life was fairly ordinary by her later activities; a primary school teacher and mother of four children. But her inquisitiveness wasn’t diminished. She liked to stay busy, and so as her youngest son entered his teens, she decided to fulfill a long harboured desire to study. Jean had excelled at Witney grammar school, leaving age 16 with a string of good grades, but, beyond professional teacher training, never had the time or opportunity to pursue higher education. She become a founding student of the Open University.

‘I remember her being exhausted. She was doing full time work at the primary school and doing all this studying as well, and looking after the family,’ says Stefan. She would talk enthusiastically about the modules she was studying in literature, astronomy, history of science, and ancient history. She graduated with honours in 1978.

Andy, Jean’s youngest son, and Stefan, talk of her commitment to human rights and justice as something ingrained, which filtered through to them in small ways, and subtly influencing their outlook on issues of social injustice. It was around this time that Jean, now in her early fifties, began campaigning for the World Development Movement, a member-led organisation that consists of local groups fighting an array of campaigns all with the shared aim of ending poverty and injustice.

But the gentle rhythm of Jean’s life changed for good when on New Year’s Day 1980 Francis Kaye died of a heart attack.

At the time of Francis’s death there was a large swell of popular concern over the nuclear arms question. The Cold War was still raging, a palpable threat to everyone.

Jean threw herself into the peace movement. She joined local peace groups, women-only peace groups, Christian CND, and regularly attended demonstrations and blockades at the RAF base at Upper Heyford, in Oxfordshire. ‘It was her willpower that was holding her together,’ says her son Andy.

In 2013, Andy’s wife Helen died of breast cancer; Jean was distraught at losing her daughter-in-law and watching her son experience the rupture of losing a life partner. While grieving Helen, Jean and Andy talked about losing Francis and her subsequent activism. ‘Had she ever thought what would have happened if my dad hadn’t died? She said, yes, she did wonder what direction her life might have gone. She would have had some involvement but it would have been different in some way.’ Referring to the years following his dad’s death, he adds: ‘It was not a complete transformation, it was a development of what was already in her. It gave her the confidence to do things.’

Religion was another factor; Jean was of a particular ilk of the devout who live their Christianity. And while she hated to miss Mass and always carried her missal, atheist women who met her at Greenham say she never preached or tried to convert. Instead she believed that to be a good Catholic, she had to fight social injustice. In an interview for the book Protest for Peace by Bernadette Meaden, Jean explained the connection between her activism and her faith: ‘The basic precept of Christianity is love. Love your neighbour, love your enemy. I wasn’t a pacifist at first, but I think I am now.’

Jean would soon find fellow Christians willing to act on their principles. There was huge activity within the Church at that time, particular after Bruce Kent’s call to arms in 1981. Speaking at a Christian CND conference at Coventry Cathedral, Kent, then General Secretary of the CND, called the mainstream church a ‘sleeping giant’. A news report of the event in the Catholic Herald said the speech was ‘rousing’ and quoted Kent as saying: ‘It will cost time, energy, money, friends, ambition and career prospects, but these are not important compared with what we’re saying … We must curb the arms race or face annihilation.’

Jean joined Dominican Peace Action, a group of Dominican Friars, nuns, and lay Christians, who followed a programme of prayer, study, and action. The friars were mostly based at Blackfriars in Oxford, a place of theology and worship operating within the University of Oxford. When Jean joined the group, they had already begun a series of radical actions against Cruise missiles.

Nuala Young, a peace activist and close friend of Jean, recalls a protest at the military base in Upper Heyford. ‘It [the base] had planes that could carry conventional chemicals or nuclear weapons. They had five ready circling the base at any one time. They could fly under the enemy wings. It was really high alert and threatening. The Dominicans actually walked out and did a sermon on the runway. The planes just roared over you. It was quite daring.’

Around thirty activists, including friars, climbed a barbed wire fence to get onto the runway, and the planes flying above were American F 1-11 bombers. Two friars and three female activists chained themselves together and began their sermon. It took the military police an hour and a half to cut through the chains and arrest them.

Jean was very much in the thick of it and loving it

The blockades at Upper Heyford continued, alongside the growth in peace camps across the country spurred on by Greenham.

‘Jean was very much in the thick of it and loving it,’says Nuala. Jean’s exploits are often remembered vividly by those who knew her.

The women wait, blinded by the inky blackness of night. The countryside is still and the winding roads open and empty.

Hidden in the dark, women are everywhere, some lying shivering in ditches; thick coats soaked with rainwater, rough and cold against their skin, bodies doused in essential oils to ward off military dog handlers, feet sore from hours of walking to find a good position. They are armed with thin, plastic bags of wet clumps of pink dough, which they call ‘gloop’.

Jean Kaye, or ‘Pankhurst’ as she is known on these nights, also waits, alert in her small car. She spots the thunderous parade of military vehicles and whispers into a transistor radio: ‘Pankhurst calling, Pankhurst calling…’ Jean starts her car and follows the convoy as it roars through the countryside, shattering the silence.

A shock of flashing blue lights cuts through the darkness as a dozen police vans hurtle along the lanes. These are followed by military support vehicles, and after that US humvees with large machine guns on top. Then come the Cruise missile launchers; the vast cylinder of metal atop a line of thick wheels seems to stretch on forever. Standing on the hill near one of the gates at Greenham Common, one can see the convoy slice its way through the countryside for miles; Jean’s car and the cars of other watchers ant-like, trailing behind.

Then angry screams and chants. At various points on the roads between Greenham Common and Salisbury Plain, where the US army practise firing nuclear weapons at Russia, peace women rise from the darkness unfurling banners and gunging the convoy with gloop.

Cruisewatch protest stop an American Cruise Missile convoy near Ludgershall on its way from Greenham Common to Salisbury Plain.

© Bob Naylor/reportdigital.co.uk

‘I [would] … go into the road with a banner, when it was safe. Most of the time you had to scurry like mad to get out of the way. But sometimes they would stop, and the feeling of empathy you had with the driver and with the earth that you were standing on was really lovely,’ says Juliet McBride, gazing out at the Berkshire countryside on a bright day thirty years later. She cocks her blonde head, smiles wickedly and the nostalgia dissipates: ‘Then you’d climb on top and wait till you got thrown off. Or arrested.’

The women crawl onto the monstrous vehicles, clasping cold metal as military guards reach to pull them away. One woman manages to stick an anti-nuclear poster on the tiny windscreen of a humvee, and another stands on the roof of a van; a slight figure with a crop of brown hair, blue eyes gleaming, legs parted as for thirty seconds she revels in her power, the American government’s nuclear weapons programme at her feet.

From about 1983, when Cruise missiles first arrived at Greenham Common, to the late eighties, the United States Air Force took out a convoy of Cruise missiles roughly once a month from the military base to a secret location in the English countryside to practise its preparations for a nuclear attack on Russia.

‘It was supposed to melt into the countryside, but because of monitoring of Cruise Watch and Greenham Women it never did,’ says Margaret Downs, a peace activist living in Oxford. Cruise Watch tracked the movements of convoys across Britain and monitored the government’s development of nuclear bombs.

Jean was an important link between Greenham Common peace camp and Cruise Watch. In time, the women at Greenham became adept at spotting the signs of an impending convoy outing. It could be the increased presence of security police around the base or the American officer’s wife living nearby in Newbury who always washed her husband’s smartest uniform and hung it outside to dry a few days before nuclear firing practice. Once the women were certain, they would spread the news to various peace groups across the country. Jean was on a telephone tree of watchers who, at short notice would jump in their cars to spend the night monitoring movements of the convoy and calling ahead to alert peace activists hidden in ditches and verges ready to spring out and protest.

Hazel’s friend Jenny was also part of Cruise Watch and spent many hours chasing convoys with Jean.

‘Every single time, every single exercise was witnessed by people,’ she says. ‘We would take the women down to Salisbury Plain so they could camp nearby. Sometimes they would camp for a night or a day. They would go and interfere with what was going on. Jean would do a lot of the ferrying women backwards and forwards, often at night. We ended up sleeping in shifts at times.’

Another Cruise watcher Maureen Wilsker lived a few streets from Jean in Witney at the time. ‘The message would come through, usually about 11pm that it [the convoy] has moved … Jean would ring me. When I drew out of my house in Bridge Street and drove up to Jean – it doesn’t sound real – but a little police car would pull out from Oscilly’s garage and follow me up to Jean.’ Her expression is incredulous. ‘Jean and I would laugh. It followed us as far as the Newbury roundabout and then another one took over.’

Mahalla Mason was also part of the radical circle living in conservative Witney in the 1980s. ‘Jean was quite serious about it. We all had these names. Coriander. Only the peace movement would have these names,’ she says smiling. ‘It was very amateur and sneered at. They sneer because you threw paint at it…[but] the theory was if paint can hit it, something much worse can hit it.’

So what did the women achieve by throwing fuschia flour bombs and paint at nuclear convoys?

‘It made an absolute nonsense of the whole thing of secrecy and being hidden,’ says Nuala. The women’s key aims were to bear witness, make known their opposition, and hinder the convoy’s procession. Slow it down, get in front of vehicles, and if they dared, get on top. Anything, to say, you are not going to rehearse nuclear war smoothly.

‘They never got one out secretly, everyone was protested or witnessed. They realized there was nothing they could do to make these things secret,’ says one Cruise watcher and Greenham woman.

After a convoy protest, Jean would drive around the Berkshire countryside collecting tired, hungry women. If they managed to interrupt the convoy, lighting fires in the road or climbing up trucks, the women were often arrested, but never charged. Sometimes they were held for hours and then deposited somewhere random, miles from Greenham or a railway station.

One Greenham woman, who wishes to remain anonymous, remembers being put into a deep, dark pit with a group of other women and left for hours. Soldiers silently paraded around the top, guns strapped across their chests, impervious to the women crying out to be released. ‘It was dark, you couldn’t see out. It was muddy at the bottom.’

Even for the Greenham women, so used to clashes with the police or challenging the military might of the US armed only with gloop and banners, it was a terrifying experience. Desperate to get out, the women attempted to provoke the officers guarding them, in the hope that they would be charged with assault, arrested and taken out of the pit. It failed. A decade later the Ministry of Defence paid the women £10,000 in damages for wrongful arrest and imprisonment.

Once popular support for Greenham dwindled and media coverage became hostile, the women left behind struggled. Life was tough and often miserable.

They had swapped their tents and caravans for ‘benders’, contraptions of wood with a thick plastic sheet thrown over. Benders were easier to dismantle and hide when the local bailiffs turned up. Evictions were frequent and without warning. Often the women were roused from sleep to the piercing beep of a reversing vehicle. Someone would shout in warning, causing the women to scamper from their benders to yank their few possessions from the path of the bailiffs’ trucks.

It was a fraught, occasionally violent, battle, happening sometimes three times a week and at other times three times a day. Newbury Council would go to the local Jobcentre and ask if anyone wanted to earn some cash in hand. The chosen were dispatched to Greenham Common with instructions, so it appeared to the women, to collect their most valuable items. When it was snowing, for example, they always took blankets first.

‘We had occasional evictions up to then, suddenly they started intensifying,’ says Rebecca. ‘The winter was bitter and very wet. You could hardly light a fire before the bailiffs would come again. It was really hard.’

A letter sent to peace activists in March 1985 describes the situation at Greenham as ‘urgent and desperate’. Written by ‘Jane T’ from Bradford on Avon Peace Action group, it says: ‘Where there used to be eight or nine flourishing women’s peace camps, there are now only [four] with a small handful of tired and depressed women at each. After the cold and wet winter and frequent evictions, they desperately need support now. Greenham Women’s Peace Camps have been a beacon of light in the dark time to millions over the world. Don’t let that light go out.’ The letter urges ‘more women to go and stay there, otherwise in a matter of weeks the peace camps may be no more’.

Rebecca was one of the women left. ‘I felt I had to be there. Almost every year, I remade the decision to be there. It was very, very hard in ‘84 because weapons had been flown in over our heads. We had a lot of media with microphones in our faces going, ‘how do you feel now you have failed?’ But there was a bit of me that felt we have not finished the job.’

We had a lot of media with microphones in our faces going, ‘how do you feel now you have failed?’

It was during these moments that the quiet, steady support of women like Jean Kaye became as important as the actions of women who danced on the silos or devised popular protests like ‘Embrace the Base’. ‘She was a quiet, positive force. A very stable sort of force,’ says Jenny. ‘She wanted so much to contribute and felt she had the time and ability, and wanted to do what she could.’

During the dark winter months, when the women were sapped of energy and struggled to stay warm, Jean, along with some other Witney ladies, would turn up at the camp with a car boot full of hot pies, stews, and crumbles. She drove from gate to gate checking that women had enough blankets and wood for fires, or if they just needed a chat. Back in Witney, she would organize the local peace women so that they each took turns to cook food or do the Greenham ‘nightwatch’. This involved sitting up all night, looking out for Cruise activity or just warding off the odd troublemaker.

‘We’d get there around 8 or 9pm,’ says Kathy Philson. ‘We would leave at eight in the morning. We all had small kids, we’d get home in time to take them to school in the morning.’ And Jean would get home in time to start a day’s teaching and check in on her mother.

But there was more to Jean than a kindly, reliable motherly figure. An Everyday Story of Women: A century of Women’s lives in Oxford, features a profile of Jean. She is quoted as saying: ‘My political beliefs at times have caused personal conflicts, for example I faced a short spell in prison whilst looking after my sick mother.’ Like many of the women, Jean’s journey to the conviction of a political ideal had been long and difficult. Thus everything related to these ideals was treasured, and on occasion she could be stern, even stubborn, if they were challenged, be it arguments over the content of a monthly newsletter or jibes from members of the public.

Jean rarely shrank from confrontation. She possessed a characteristic common to nearly all Greenham women; a willingness to question the laws they were regularly accused of breaking. This meant she was always calm in the face of potential arrest. During one ‘Grannies against the bomb’ protest outside the US Embassy in London, a group of women chained themselves to the building and blocked the main entrance. After a few hours the women decided they had caused enough disruption, unchained themselves, and packed up to go home. They left the gate chained up, which meant people were still unable to use the door. A policeman approached the women.

‘Now, there’s a nice chain and a padlock here,’ he said. ‘Whose is it?’

The women were silent; if they produced the chain and padlock, they would almost certainly be arrested.

The policeman said, ‘Listen, if you have got the key, you can come along and unlock the padlock, and take your padlock and chain home and use it again another time.’

Jean looked up, pulled the key out from her bra and said: ‘Thank you very much. That cost me a lot of money.’

Stefan drove from the airport to Oxford where his mother lay unconscious and unable to talk. Jean Kaye awoke the next day, 16 September 2013, and spoke her last words: ‘I think I may be dying, but I don’t mind. I have had a good life. I’ve got four lovely children and grandchildren, and I love you all.’

Part 4: The Legacy of Greenham Common

Greenham women began the 1980s imagining a molten world victim to the posturing of the men who ruled it. In this vision, only children survived, swollen and deformed by a nuclear winter, while they stood in silent horror, helpless. Their angst was neither niche nor hysterical; it was shared by many a public intellectual, scientist, author, and politician. British author Angela Carter was vociferous in her disdain for the rationale for nuclear weapons and urged women in 1984 to ‘rage as if against the dying of the light.’

For a decade women raged. Following the first ‘Women for Life on Earth’ march from Cardiff to Greenham Common, women disrupted activities on military bases across the country. They protested against the bombing of Libya, supported the miners, raged against Section 28, the first Gulf War, and would go on to mobilise support for women in the Balkans. They stormed Parliament, and stood for Parliament, staged sit-ins, occupied buildings, defaced war machines, wrote letters, books and poems, danced and sang songs. They travelled to Europe and Russia, gathering ideas and inspiring others. They left home, school, and work to live in the open under great sheets of plastic where they plotted the end of the nuclear age.

Meanwhile, like a row of falling dominoes, the global political tenets propping up the possibility of nuclear war collapsed. By the start of the new decade, Cruise missiles had left Greenham Common, Mikhail Gorbachev shook hands with Ronald Reagan and the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty was signed. Revolution raged across Soviet Europe. Boris Yeltsin called George Bush Senior to tell him about the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Soon after, the two men signed the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, or START-1, to reduce strategic nuclear weapons.

Still the Greenham Common women’s movement lived on despite this new political environment and the removal of Cruise missiles. The women were by now exhausted, burnt out, and sometimes bitter after years of rough treatment and living outside in tense conditions. The camp had always been fractured with arguments; it was part of Greenham life. But towards the end, a permanent rupture occurred so that two camps emerged. Depending on which Greenham woman is remembering, the camp ended in 1993, while another will say it ended in 2000 when the last women left and the Common was returned to the people of Newbury. The reasons for the split are always vague and half forgotten, but the hurt and regret still linger.

In spirit, though, the movement lived on exercising a powerful legacy over the women touched by it. Those who once raged against nuclear holocaust redirected their attention to other social ills. Greenham was a place of education where women learnt, first about nuclear weapons, then about how best to challenge social and structural injustice. They learnt how to organise and protest, how to use the law and the media, and they learnt how to forget the fear of speaking out. Each Greenham woman learned these lessons, and each lived the legacy in her own way.

Jean Kaye had finally retired and moved to Oxford by the time the Cruise missiles left the base. The impact of Greenham on her life was enormous. After a long career as a primary school teacher, she became a full time campaigner for social justice up until her death in 2013.

‘I have four sons and it was the result of living in an all male household that made me become more feminist,’ she said in an interview for An Everyday Story of Women: A century of women’s lives in Oxford. ‘Living at Greenham Common made me more politically aware. I have always been concerned about the effects of nuclear weapons and this has widened to include issues concerned with peace and justice.’

When a youth prison was converted into an immigration detention centre in 1993 at Campsfield on the edge of Oxford, Jean, now 67, was outside protesting against the Home Office. It was one of the first centres to open in the UK. Jean joined a visitors group and came to know some of the asylum seekers and migrants being detained. ‘She asked me if I would like to become a visitor,’ says Gill Baden, an old friend of Jean’s who now volunteers full time for Bail for Immigration Detainees in Oxford.

‘I went in with her to get the hang of it. At that time detainees were very suspicious of us and they would say, ‘don’t speak with these women, they are from the Home Office.’’ Gill smiles at the memory. ‘Jean was very convincingly not from the Home Office.’

Immigration detention centres are harrowing places; the air of desperation and panic is almost palpable in the visitors’ room. Jean was not the pitying type; she wanted to do more than offer friendship and occasional visits. She became active within the charity, Asylum Welcome, which had been set up in response to the detention centre and the inflow of refugees fleeing the Yugoslav wars.

Jean founded Asylum Welcome’s education division to help asylum seekers waiting to regularise their status. Alongside English lessons, she offered personal advice, and forged relationships with local further education colleges and universities willing to take on refugees for home student fees. ‘I still know people in Oxford who are British citizens who qualified through her initial efforts to get them started to learn English and then do things like engineering,’ says Gill.

Sister Bernadette began teaching English as a second language (ESOL) in Oxford in 1999, and was soon introduced to Jean, who joined the education team. ‘We worked pretty hard. She [Jean] saw the great value for education in their lives,’ she says. ‘She had absolute steel will. If she felt something was unjust with the government policies towards these people, sometimes I saw her really angry. I know I feel it myself too. The Home Office policies kept changing all the time. She would be very frustrated at what she saw as the lack of justice.’

One of Jean’s clients was a young man from Kosovo. When he first arrived in Oxford he spoke enough English to get by. After some years he graduated with a 2:1 degree in international politics from Oxford Brookes University. By now, his English was excellent and he was able to support himself through work as an interpreter. Jean had encouraged and supported his education and he in turn volunteered for the charity. The relationship ended when the Home Office refused his application for residency. But, rather than challenge the decision, he decided to return home because, armed with a degree and high level of English, he felt he might be OK.

‘Many a time I have heard, especially some of the young men, I have heard them say to her, ‘you are mother,” says Sister Bernadette. ‘They had this tremendous love and respect for her.’ And Jean loved them back. For her it was more than charity and she treated them as friends, inviting to her birthdays, providing sureties, and helping them find work.

Jean always said she would stop at 80, but continued supporting refugees up until a few years before her death. The octogenarian remained an active campaigner for peace. Among her books and theatre programmes, Jean left behind a giant stack of letters with the House of Commons logo, evidence of persistent letter writing. Greenham really was just the start. Over the years she would picket Jack Straw’s house in protest against the second Iraq war, regularly read the names of dead Afghans and British soldiers in London and Oxford, and was a stalwart minute-taker at Christian CND meetings. Most years since Cruise missiles left Greenham Common, she attended a monthly women’s peace camp at Aldermaston, a military base a few miles down the road from Greenham where British nuclear warheads are developed. She never really gave up her life of protest.

Today the United Kingdom’s nuclear weapons are maintained and developed by a consortium of private companies under umbrella organisation the Atomic Weapons Establishment. AWE runs several sites across the country, including two at Aldermaston and Burghfield, situated between Hampshire and Berkshire.

Around 7am one day in October 2013, Angie Zelter sets up camp outside the entrance to AWE Burghfield, where the last stage in assembling nuclear warheads takes place. With her are fifty men and women from Knighton, Cardiff, Aberystwyth, and Swansea. The protest occupies a stretch of land outside the factory, facing onto a busy motorway. Some of them chain themselves to the gate, several others dance under a glorious red dragon puppet, and someone else puts up posters. One reads ‘Schools, hospitals, affordable housing, care for the elderly or an unusable nuclear weapon?’

The Welsh Dragons blockade against the replacement of Trident lasts several hours and as they sing peace songs and the Welsh national anthem drivers slow down to hoot in support. Angie is pleased with the blockade. Action AWE is one of many groups she has set up since Greenham Common to protest the UK’s continued development and maintenance of nuclear weapons.

‘How many decades do you have to carry on? My son says, ‘Why are you still working against nuclear weapons, you have been working on this since before I was born.’ And he is 38 now. It is hard sometimes,’ she says with thoughtful certainty, which makes it hard to imagine she entertains such doubts for long. Indeed, she adds, ‘Why should they get away with this stuff? We should protest. If you allow evil to happen in your country then awful things happen. A lot of things happen because we allow them to happen, and we don’t protest about it.’

When she was younger Angie spent three years working in Cameroon on development projects for the poor. One day, a local challenged her reasons for working in his country. He asked, ‘Why are you here? Why don’t you go home? That is where all our problems come from.’ His words resonated at a time when Angie was coming to terms with how little she knew about the world’s problems.

‘I thought, how could I go through my whole university career and not know about acid rain, climate change, nuclear weapons, poverty, all the major issues of our time?

‘I went over to Cameroon for three years and saw with my own eyes the impact of colonialism and exploitation by big businesses, what impact it had on local people. I thought, actually it’s my country involved in that, so I need to go back and work in my own country.’

Ever since, Angie has carried out a series of non-violent direct action protests designed to raise awareness and challenge the government promotion of profit and business over environmental justice and human rights. Her campaigns are always imaginative and thoughtful; whichever part of the establishment is under attack has to engage with the issues before dismissing the protest.

One of Angie’s biggest protests during the 1980s was the Snowball Civil Disobedience campaign. It started with three people cutting a single strand of the fence around any US military base in the UK and then writing a letter to the British government asking them to take a single step towards nuclear disarmament. Each person then returned to the fence, this time with two new people, who would do the same. It continued until hundreds of people took part; most Greenham women remember the campaign.

Angie is convinced that this sort of direct action can bring about change. During the early 1990s, while campaigning for the protection of rain forests, she did a lot of ethical shoplifting. This involved going into shops and pocketing anything made with Brazilian mahogany. She would then take the items to a police station to report it stolen by industry from indigenous reserves. Part of this campaign involved occupying the offices of timber importers.

‘At the time we started, they had no idea where their timber was coming from. Now they know. That had an impact.’

Perhaps one of Angie’s most well-known and successful actions, the destruction of a British Aerospace Hawk jet destined for Indonesia, was part of the peace group Swords to Ploughshares campaign. In January 1996, three activists caused £1.5m worth of damage to the plane at a BAe factory in Lancashire. In court, the campaigners’ message moved the jury. The activists’ defence rested on the fact that by damaging the jet they were trying to prevent genocide. The Hawk would almost certainly be used to commit human rights abuses against the people of East Timor.

‘We spent six months in prison and we won that court case,’ says Angie. ‘We were found not guilty and in a way that set up a feeling of hope.’

It is this resolute hope that spurs Angie to encourage others to protest, not just in the UK, but across the world from Palestine to Sweden. In 2012, she was invited to South Korea to help the country’s growing peace movement protest against the American military bases being built there. ‘There is a whole village involved,’ she says in wonder. ‘They’ve been involved in direct action for about eight years.’

After the Hawk jet case, Angie set up Trident Ploughshares to campaign for the disarmament of Trident, and in 2006 helped start Faslane 365, a year-long blockade of a nuclear base in Scotland. It was here, spending the year at Faslane military base, that she concluded, ‘You don’t need very much’. She elaborates: ‘I don’t pay my fines and the bailiffs come for me, there is nothing to take. I don’t run a car, I don’t have a fridge, I don’t have a TV. The more you have, the less free you are.’

This, in a way, is her call to arms. But the 62-year-old mother and grandmother is one of a kind, and knows this. She adds: ‘When you are raising kids, especially as a single mum, then that is what you have got to do and that is very important. Or you might be a doctor or nurse or librarian. But you should be aware, as a global citizen, of what is going on around the world. At every single level we should not be allowing certain things to happen. We should be speaking out.’

Angie’s persistent protest is one reason Rebecca Johnson is still excited after thirty years of campaigning for the multilateral disarmament of nuclear weapons.

‘Whenever I feel low and despondent, I get together with some friends and I work out a new strategy,’ she says.

Rebecca is an engaging communicator; wearing a long black coat and black flapper hat over her chestnut bob, her thoughts flow in perfect paragraphs. It is immediately obvious why she was able to carve out a career advising governments and nuclear scientists after leaving Greenham.

‘So two things came out of my last feeling of despondency. One was talking to Angie and a couple of others. We decided we needed to launch what then became Action AWE,’ she says. ‘The other strategy that came out of it earlier was about mobilising the nuclear-free countries to get a nuclear ban treaty.’

Rebecca has worked in disarmament diplomacy ever since she left Greenham Common. Originally she wanted to become an academic, but in 1982 went to Greenham and stayed there for five years. Rebecca dived into the heart of the women’s peace movement and took part in the most daring public actions, dancing on the silos, standing for Parliament against Michael Heseltine in the ’83 election, and occupying the air traffic control towers at Greenham. She is someone many women from Greenham remember.

Photo by Lesley McIntyre

Like all Greenham women, Rebecca spent a lot of time thinking about what to do after she left the Common. How to challenge the proliferation of nuclear weapons and convince the general public that peace was, in fact, the sane option. When politics failed, she tried the law. On 9 November 1983, Rebecca and ten other women from across the UK filed an injunction against US government to stop cruise missiles leaving America.

The women filed a case in the Federal Court in New York arguing that cruise missiles were illegal according to international and constitutional law. They compiled witness statements from academics, scientists and doctors on the effect of long term radiation resulting from a nuclear explosion, public health risks, and the practicalities of dealing with burn victims. They compiled witness statements on environmental damage and presented a military strategy expert to certify the likelihood of weapons being deployed. One, Margaret Thompson, even gave evidence on the fallibility of human beings who control nuclear weapons. They rustled up a Nobel peace prize winner and lawyer, Sean MacBride, who testified to the illegality of nuclear weapons.

They lost and knew they would. What was more important to them was the political act of making the case. It also meant everyone was better informed, which is at the heart of Rebecca’s current work; raising awareness by sharing information with everyone from grassroots activists to UN dignitaries to preoccupied members of the general public. Rebecca speaks in admiring tones about ‘young people’ organising on Twitter, and claims to be ‘useless’ at it, but actually, she possesses the key qualities: political nous, a succinct campaign purpose and unwavering conviction.

It took a close friend to convince Rebecca these qualities might be useful once the Cruise missiles left Greenham. ‘I had been living outside a nuclear power base for the last five years,’ she says, even now slightly surprised at her younger self’s lack of a plan. ‘We were a bunch of anarchists, but you did have to organise nonetheless to get things done, you just had to find different ways. We were very strategic at Greenham.’

The Cold War was over, but the issues still burned strong for Rebecca. Playing on her mind, in particular, were the women from the Pacific Islands who gave talks at Greenham describing the impact of British, American, and French nuclear testing on their lives.

‘It was shocking. They had been 13, 14 when the testing happened. It all came down as flaky, white stuff. They thought it was snow and they played in it,’ she says, at once incredulous and angry. ‘Then when they had babies. What they had was, one woman described it as jellyfish babies that lived only a few hours before [they] died. These young women had been contaminated by the radioactivity from nuclear testing by the UK, from the US, from France, the major nuclear states destroying the lives, the health, the environment of the Pacific Island. They came to Greenham and taught us.’

‘I kept in my heart what they had told us, so that after we got the treaty [Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty] at Greenham personally I was ready to go. I was ready to leave Greenham. But I was not ready to leave campaigning.’

Rebecca went from Greenham to working for NGOs such as Greenpeace International, where she campaigned for a comprehensive nuclear test ban treaty. Around this time, she also began to write long complex emails to civil servants setting out all sides of the nuclear debate, not just disarmament, about how best to draw up a treaty, the flaws of the 1968 Non-Proliferation Treaty, and what role non-nuclear countries should play. This was based on the experience she was collecting at an international level, talking to scientists and continuing to work within the grassroots protest movement.

‘My emails were what we would now call blogging. It was the early 1990s.’ Her emails were popular in circles of power in Washington and Geneva where she often worked. Diplomats from developing and non-aligned countries also got in touch: ‘I was able to provide them with information about what the major nuclear-armed states were doing to undermine the objective of the treaty.’

In 1996 Rebecca set up the Acronym Institute for Disarmament Diplomacy publishing books, articles and offering consultancy. Past clients include Hans Blix, who she advised while he was head of the International Weapons of Mass Destruction Commission.

Rebecca continues this work today. Most of her time is spent galvanizing and lobbying non-nuclear countries, who in the past have often had little say in multilateral disarmament agreements. To this end, Rebecca works with civil society from countries including Mexico, Egypt, South Africa, New Zealand, Brazil, Ireland, Sweden, to work on a full disarmament treaty without the nuclear-armed countries who continue to stall.

And from the lofty heights of international diplomacy Rebecca is still able to glide easily back into grassroots peace protesting, attending camps and marches, campaigning for CND, and working with groups such as Women in Black. She even gave talks at Occupy in both New York and London, eager to encourage this generation of mass direct action protests. ‘We pick up each other’s stories, but we transform them for own age. Each age is different, but the core principle of non-violence remains the same.’

For Lesley McIntrye the legacy of Greenham Common Peace camp was to play out differently. She too was unafraid to challenge the received wisdom on nuclear weapons and was consumed with anger. She was already sensitive to injustice having spent the years leading up to Greenham in Zimbabwe campaigning for independence and equal rights for black Africans.

But Lesley stood apart from the other women. When passions ran high, she would often step out of the moment, pick up her camera and snap. Lesley was captivated by the women’s fearless desire for peace.

‘I had a feeling that I was photographing something that was historic, unprecedented and absolutely felt like a continuum of the suffragette movement. I was very conscious of that. I found it both emotionally and intellectually and visually fascinating.’

There were also times when Lesley put aside her camera and lunged to cut the perimeter fence, overtaken by fury when the Cruise missiles arrived at the base.

She first came to Greenham Common on a wintry November day in 1982. She immediately felt oppressed at the bleakness and alienation of the military surroundings. Then she saw the peace women.

‘This cluster of umbrellas above women, just sitting in constant rainfall, talking. Talking about tonnage and cruise missiles, and issues in and around non-violent direct action, what they were doing there, why they were there, as if the weather was completely irrelevant.’

Before long Lesley was hurtling up and down the M4 between the ramshackle flat she shared with her sister in Brixton to a tent in Berkshire. ‘I did feel it was where I should be.’

She helped create a campaigning newspaper called the Greenham Factor. It contained images, reports of actions, and interviews with peace women. ‘I laid it out on my kitchen table and literally cut and paste manually.’

Lesley thrived on the creativity and debate while she was at Greenham. ‘It was an inspired process. The women just came up with, time and time again, pretty inspirational ideas to keep journalists interested. How do you do it? How do you protest? How do you make it something which is symbolic, non-violent and really catches people’s imagination?

‘I talked to the police and some of them were supportive of us being there. They had wives who were supportive of the Greenham women. It really split people…it was complicated. Some policemen said, ‘This is great, I am getting so much overtime, we can afford a fridge freezer.’ But others were saying, ‘keep on going girls, my wife thinks it is great you are here.’ It wasn’t always predictable how people would respond.’

The women used the bright green broadsheet to raise funds for the camp; Lesley would travel to places like Holland and Germany, armed with stacks of the Greenham Factor giving talks in bookshops to rally European women to join the movement.

Caught in a whirlwind, Lesley felt no desire to earn a living taking fashion or commercial photographs, instead Greenham was her muse (her images were later chosen for the World Press Exhibition). So she took photos, protested, got arrested, and wrote – until October 1984 when she gave birth to Molly.

‘I was told she would never leave the hospital. And so what happened to me was I had to disappear into the world of facing my own child’s mortality.’

The 1981 Education Act was an incredibly important piece of legislation for the rights of children with special needs. It stipulated that local education authorities and mainstream schools had a duty to support the education needs of disabled children and those with learning difficulties. Lesley came to know the law because Molly lived.

‘The initial diagnosis was so bleak. Then we took her home and she started living longer than they expected. It was always very uncertain.’ Molly had an abnormality in her muscle formation, which made it difficult for her to walk without support. The condition was life limiting, but never fully diagnosed. For the first few years of Molly’s life, the family lived in Norway. Lesley’s ex-husband was offered a job in Oslo and Lesley worked for a political newspaper taking photos of strikes and immigrants. The couple eventually split, and Molly and Lesley settled in London. ‘Everything I had planned changed instantly. I could only take London-based work, travelling was impossible. I did take her to Greenham in a buggy, a tiny wee thing, but it is not an easy place to be. I didn’t have the stamina.’

Lesley’s immediate concern was to make Molly’s life wonderful because she had no idea how long it would last. ‘I was so contained by this child, everything changed. I couldn’t take on many commissions, but I was already too much of a photographer not to have taken photographs. So I carried a camera all the time, I started recording the day to day reality of our lives. I accessed this world of children and holidays and school. I just recorded everything I could.’

The fight began when it was time for Molly to attend school. ‘I had a perfectly sentient child who needed to use a wheelchair and because of the lack of clarity in the Education Act when Molly was born, I had the formidable task of getting her into a mainstream primary school and in getting her transferred to a mainstream secondary school.’

Under the new Act, local authorities had to provide each child with a special needs statement, which gave an account of those needs and specified how they should be met. There was plenty of wriggle room for authorities that wanted to save money and avoid setting a precedent. The statement ultimately determined how much money would need to follow the child. If an education authority deemed a particular need unimportant to a child’s ability to learn, one example in Molly’s case was wide corridors to accommodate her wheelchair or accessible toilets, they could refuse. Molly was appraised every year.

‘For the whole of her life I had a solicitor. I ended up a vociferous campaigner for the rights of children with special needs to access the education system.’ And so Lesley battled the education authorities of South London and found herself in the fraught position of trying to convince countless councillors that her child’s life was not pointless, however uncertain or short it might be.

What I learnt at Greenham, you campaign on all different fronts if you have something you are passionate about.’

First, she sought to get Molly into a mainstream school every year. Then she set up the Lambeth Special Educational Needs Forum whose members were parents, head teachers, and ‘as many people as possible’.