Graffiti is such a nuisance. Random scribbles and crude images cluttering up the walls of our urban spaces. Yet, one man seems to have achieved the unthinkable: he’s made graffiti beautiful. More than that, he’s transformed this dreary grey world into his canvas.

Known only by his moniker, Banksy, with which he signs his work, this elusive artist has risen from stencilling the streets of Bristol in the early 1990s to international fame. His work now decorates cities across the world. Despite global acclaim, his anonymity is guarded carefully and Banksy himself rarely gives interviews. He doesn’t need to: his work speaks for itself. True to the graffiti code, he sprays images and statements designed for a fleeting glimpse as your car whizzes past: easily spotted and quickly recognisable. Yet, viewing a Banksy will undoubtedly leave you thinking. Renowned for anti-establishment and often politically charged graffiti, a Banksy piece is obvious for its ability to challenge the status quo. One of his most famous pieces, the ‘bunting boy‘, depicts a young boy hunched over a sewing machine while he stiches the Union Jack together. Choosing to spray this piece on the wall of a Poundland store is message enough. Similarly, his ‘Napalm‘, a version of a photograph from the Vietnamese war of a terrified naked girl, altered to include Mickey Mouse and Ronald McDonald, merges an iconic photograph with popular figures. It blends the American domestic ease of consumerism with uncomfortable foreign policy realities.

The genius of these pieces goes beyond imagination or beauty; instead, it’s to be found in their accessibility. Often framed by weather-beaten bricks, his work emulates the power of graffiti as a chosen art form: it’s open to everyone equally. And it’s to everyone that Banksy sends a message with each and every piece: think.

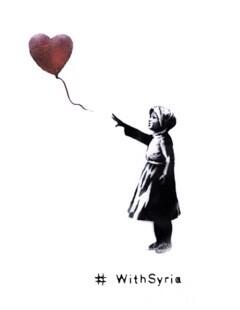

Thinking is certainly the key trend in one of his more recent pieces. To mark the third anniversary of the Syrian civil war, Banksy has re-hashed an old favourite from 2002: the girl with the heart balloon. The original is, arguably, one of Banksy’s most evocative pieces: a young girl with windswept hair reaches out from her black and white world for the single splash of colour – a heart-shaped red balloon. The text reads:

‘There is always hope’.

Simple yet powerful. With its unadorned beauty and sweetly optimistic message, it will unquestionably brighten the day of any passer-by.

Adding his weight to the #withsyria campaign, Banksy altered his original to depict a Syrian girl, wrapped in a headscarf, reaching out for a bruised-looking red-heart balloon. Displayed on his website for a short-time, this new version came with a message from the artist himself:

‘On 6 March 2011 in the Syrian town of Daraa, fifteen children were arrested and tortured for painting anti-authoritarian graffiti. The protests that followed their detention led to an outbreak of violence across the country that would see a domestic uprising transform into a civil war displacing 9.3 million people from their homes.’

Banksy has transformed the very means of expression that sparked the Syrian conflict from a simple case of youths decorating a wall, into a frieze of the consequences that can’t easily be ignored.

withsyria

What, then, does the Syrian girl challenge us to face? Firstly, we must face the innocent. A young girl, caught up in a conflict over which she has no control is regretfully reaching for a heart. We don’t know whether it’s for the family that has been lost or a future in doubt. We don’t need to. Secondly, we must face our regrets. A bruised-looking heart drifting out-of-reach conveys a powerful sentiment: much has been lost already and there is much to be regretted. This small, sad figure cannot reach the balloon of her own accord and, if we are to stop the mountain of regrets building higher, we must help her.

On the 15th March 2014 the Syrian girl was displayed on landmarks around the globe with another message: ‘give hope’. Exhibited at places like Trafalgar Square and the Eiffel Tower, the poignancy of the display was supplemented by the candle-lit vigils held to mark this unwanted anniversary. The #withsyria campaign, a coalition of over a hundred humanitarian groups and non-governmental organisations, held the vigils and encouraged people across the globe to release their own red balloons. #withsyria also released a Banksy-inspired video to mark the third anniversary. Narrated by British actor Idris Elba and with music by Elbow, we see a young girl desperately trying to grab her own red balloon. As she catches hold, she’s lifted over a wall and the awful conflict raging below becomes visible. A single tear rolls down her face. She’s then joined in the sky by thousands of others all holding their own red balloon. Throughout, graffiti text tells the facts accompanying this tragic plea for help: over 100 000 people killed, half the population displaced.

Despite the anguish in its message, the video offers hope. Whilst Banksy may have created a Syrian girl with an inescapable message, the suffering she has endured can be escaped. There is hope that those trapped in the midst of the conflict can yet rise up from the smoke; clutching onto those red balloons. Yet, to achieve this peace and return heart to the people of Syria, we must stand with them; as Banksy states, we must give them hope. So, with this in mind we are left only with a message from Idris Elba at the end of the video:

‘Will we let the people of Syria lose another year to bloodshed and suffering? Will you stand with Syria?’