Lebanon has suffered brutal conflict for over one hundred years, ever since the First World War turned it into another of its battlefields. How have those who’ve remained survived? How does the country subsist? Marina Chamma reports on the history of her home nation, the lives that continue and flourish there, and the optimism that vies with pessimism in the face of repeated violence.

The Middle Eastern front during the First World War is romanticized in the adventures of Lawrence of Arabia and by the exploits of youthful Arab revolutionaries, but its repercussions for what is now Lebanon were anything but romantic.

“The children of my country, dear Mary, the people of Mount Lebanon are being killed by a famine at the hands of the Ottoman government,” wrote the Lebanese poet and philosopher Gibran Khalil Gibran in May 1916 to his American patron and one-time lover Mary Haskell. “80,000 people have perished until today and thousands of others die every day.”

A few months into the First World War and the Ottoman Empire had begun to feel the heat of a losing battle. The administration was aligned with Germany and the Central Powers; the implications for what was then Mount Lebanon would be devastating.

In 1915 Jamal Pasha, nicknamed “the butcher”, was appointed commander in chief of the Ottoman forces in present-day Lebanon and Syria, but was unsuccessful in combating British forces in the region. In an attempt to starve his enemies of supplies Jamal Pasha set up a blockade over the eastern Mediterranean and in the process disrupted food supplies for the people living in Mount Lebanon, which exacerbated the grim effects of famine and a locust plague of the likes never seen in the region.

The great famine led to Lebanon’s second major wave of emigration (the first was in 1861), cementing its trademark Diaspora throughout the world, both a weakness and strength to the homeland.

The 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement carved up the Middle East into artificial nation-states on the basis of imperial interests. Mount Lebanon turned into an over-sized version of itself, with the declaration of Greater Lebanon in 1920 (under a French protectorate until Lebanon gained its independence in 1943). This further exacerbated already tense sectarian and social dynamics, the effects of which would be felt time and again in the decades to come. Meanwhile, the 1917 Balfour Declaration, whereby the British government supported Zionist ambitions to create a Jewish homeland in Palestine, produced a deadly time bomb that erupted with the declaration of the State of Israel in 1948 and the ensuing catastrophe for the Palestinian people. This seemingly never-ending tragedy that has cast a dark shadow over the entire Arab World and been a catalyst for many regional wars, has also affected Lebanon directly, if only given the tens of thousands of Palestinian refugees it still hosts.

But as big a mark as the Great War made on Lebanon, many other wars came to replace it. Since 1918, Lebanon has dealt with regional wars it had little say over, as well as its own internal struggles. Each battle, whether the 1975-1990 civil war, the undeclared conflict with occupying Israeli and Syrian forces, the July 2006 Hezballah-Israeli War, or political assassinations, was thought to be the bullet of mercy pronouncing the end of Lebanon’s existence. Yet somehow Lebanon survives. War and violence have become part of the country and people have learned to live with it, always alert to the possibility of violence and tragedy around the corner.

Living with war

A reality defined by the spectre of war, conflict and violence is a strange one to describe and live in. Then again, if this reality is your home, as it is mine, then it is normal. You learn to deal with it and sometimes – sadly – even ignore it.

So it is not unusual to have a part of the country going about its regular business just kilometers away from ongoing deadly street battles. In fact, whenever conflict seems imminent we have a saying, “If it doesn’t get bigger, it won’t get smaller”: a conflict must explode and let off steam, otherwise it will never be resolved.

In the years after the civil war ended in 1990, Lebanon sought to fight back against its image as a country always at war. The quintessential description of Lebanon, exemplified by its capital Beirut, known as the city “that will never surrender,” became resilience. There seemed to be an unspoken agreement that no matter how many bombs exploded and civilians murdered, the people would always respond. Collectively they would get back on their feet – by clearing the rubble, rebuilding what had been destroyed, mourning loved ones by refusing to leave the country, staying put for the sake of Lebanon – and leading a kind of life against the odds. To make up for lost time spent fighting, governments poured money into rebuilding shattered cities (well, mainly just Beirut) and adapting to an economy of peace.

There seemed to be an unspoken agreement that no matter how many bombs exploded and civilians murdered, the people would always respond.

In the midst of war and end-of-conflict rebuilding, life for the people of Lebanon continues in the same ways it does in countries free of violence. There is the sweetness of grandparents caring for their grandchildren and the bitterness of losing loved ones to a terminal illness; the fun of a boisterous night out with friends and endless Sunday family lunches; the anxiety of finding a new job and making ends meet every month. But we also cope with the unique daily challenges of Lebanon; electricity shortages, poor physical infrastructure, and widespread sectarian and political nepotism that crowds out merit-based employment and social advancement.

Many Lebanese, including myself, choose to remain in or return to Lebanon despite all the hardships and challenges. I returned to Lebanon, even while knowing that a calmer, more predictable and financially attractive future would await elsewhere. But many leave, as they have done in the past, unable to reconcile themselves to the turbulence, deciding instead to keep their homeland always close to their hearts but at healthy distance from their souls. Lebanon is not for the faint-hearted.

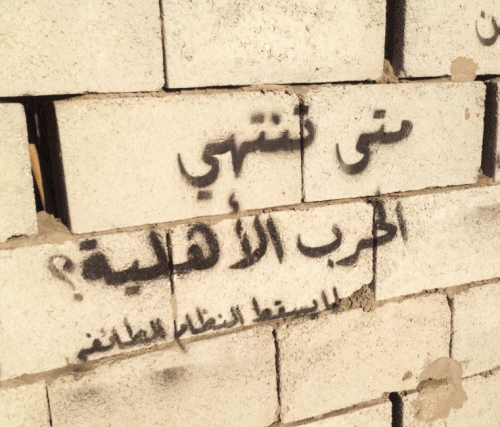

When will the war be over?

The fact that Lebanon has survived geographically unscathed and has avoided being split up among confessional lines is part reason, part miracle. It is reason because after almost a century since the establishment of Greater Lebanon in 1920, one cannot deny the certain bond that has developed among people brought together by colonial whims.

Indeed, many are convinced that what defines Lebanon is its diversity. So that Lebanon wouldn’t be Lebanon without its religious, cultural and ethnic diversity, without its South and North, or without the Bekaa Valley connecting the sparkling shores of its capital Beirut to the Arab hinterland.

Lebanon’s survival is also a miracle. It is a miracle because with every conflict, bombing or political stalemate that drags on too long, people begin to grow apart. Many have taken refuge in narrow geographical, sectarian and confessional frameworks for the lack of a clearly defined Lebanese identity to provide protection and a sense of belonging. A Lebanese politician once described Lebanon as being, “Too big to be swallowed and too small to be partitioned.” It is a theory constantly put to the test.

Lebanon’s survival is also a miracle. It is a miracle because with every conflict, bombing or political stalemate that drags on too long, people begin to grow apart.

But whoever said that a war ends when the guns fall silent? In the years following the end of the civil war in 1990, Lebanon transitioned into peace, or rather the cessation of hostilities, without the will to find convincing answers and explanations for what had happened. There wasn’t a reconciliation process to heal the scars of war, and nothing written in the history books told us how to learn from the past and avoid repeating the same mistakes in the future. Lebanese history books, at least those taught in schools, stop at 1943 when the country gained its independence from France. Due to the highly political and sectarian nature of the civil war and society itself, local parties have failed to agree on a unified, comprehensive and authoritative account of Lebanon’s contemporary history. Artists and private intellectuals have tried to fill these gaps, but how can a song or a painting heal a nation’s damaged soul? It can feel as if the war never really ended at all.

“When will the Civil War end?” Beirut

Lebanon still suffers from a similar sectarian, confessional, feudal, family-based system and economic inequality that has brought it so much bloodshed throughout the years. These tensions have also steered the course of Lebanese society away from a secular, merit-based, just, stable and prosperous democracy it must aspire to. But how can we move on from war when the country is slowly poisoned by corruption? How can a country begin to heal when around 17,000 families are still looking for loved ones disappeared during and even after the civil war? Lebanon cannot leave war behind if no effort is made to understand and identify the reasons for deadly clashes and political assassinations that have taken place in the two decades since the civil war ended. Instead, political leaders and much of the population itself, hide behind the notion of Lebanon’s resilience and its ability to survive. A condition of this survival is that we move on and never look back.

Hence resilience might have kept the country from falling apart, but has not helped in truly bringing it together. Resilience is surviving but not coming to terms with the past.

We must also face the fact that there can be little hope of a peaceful future while our current crop of leaders are the same men who led us into the violence of the last civil war. Those who fought in times of war can never lead in times of peace. Never.

A question of survival

The centennial of the First World War comes at an increasingly unstable time in world history, not least for the Middle East and Arab World. Barely three years since the outset of the so-called Arab Revolutions, the region sees itself back to where things started and even worse.

With seemingly never-ending violence and spreading extremism, many now regret the euphoria of the 2011 spring that turned into an ominous winter. And although three years is nothing in the ocean of history to properly assess the outcomes, the outlook is looking bleaker by the day. For Lebanon, however, there is always room for optimism. The country has survived time and again, and will do so again. But, as always with Lebanon, there is pessimism too. Survival comes at a cost; when the fabric of society is torn apart by war, how do you put it back together again? Lebanon must answer this question.

“You have your Lebanon and I have mine,” Khalil Gibran wrote in 1920 from the US, at around the same time that Greater Lebanon was proclaimed. “You have your Lebanon with her problems, and I have my Lebanon with her beauty. You have your Lebanon with all her prejudices and struggles, and I have my Lebanon with all her dreams and securities.”

Almost a century ago, Khalil Gibran recognized that Lebanon meant different things to different people, something which continues to hold until this day. It is time for it to mean one thing to everyone.

Photo by Bertil Videt